1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Reference Manual for the Standardization of Geographical Names United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names

ST/ESA/STAT/SER.M/87 Department of Economic and Social Affairs Statistics Division Technical reference manual for the standardization of geographical names United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names United Nations New York, 2007 The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environmental data and information on which Member States of the United Nations draw to review common problems and to take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint courses of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises interested Governments on the ways and means of translating policy frameworks developed in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities. NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of material in the present publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The term “country” as used in the text of this publication also refers, as appropriate, to territories or areas. Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. ST/ESA/STAT/SER.M/87 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. -

Combining Diacritical Marks Range: 0300–036F the Unicode Standard

Combining Diacritical Marks Range: 0300–036F The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0 This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0. Characters in this chart that are new for The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0 are shown in conjunction with any existing characters. For ease of reference, the new characters have been highlighted in the chart grid and in the names list. This file will not be updated with errata, or when additional characters are assigned to the Unicode Standard. See http://www.unicode.org/charts for access to a complete list of the latest character charts. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the on-line reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 4.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this excerpt file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0 (ISBN 0-321-18578-1), as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24 and #29, the other Unicode Technical Reports and the Unicode Character Database, which are available on-line. See http://www.unicode.org/Public/UNIDATA/UCD.html and http://www.unicode.org/unicode/reports A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. Fonts The shapes of the reference glyphs used in these code charts are not prescriptive. Considerable variation is to be expected in actual fonts. -

Chapter 5. Characters: Typology and Page Encoding 1

Chapter 5. Characters: typology and page encoding 1 Chapter 5. Characters: typology and encoding Version 2.0 (16 May 2008) 5.1 Introduction PDF of chapter 5. The basic characters a-z / A-Z in the Latin alphabet can be encoded in virtually any electronic system and transferred from one system to another without loss of information. Any other characters may cause problems, even well established ones such as Modern Scandinavian ‘æ’, ‘ø’ and ‘å’. In v. 1 of The Menota handbook we therefore recommended that all characters outside a-z / A-Z should be encoded as entities, i.e. given an appropriate description and placed between the delimiters ‘&’ and ‘;’. In the last years, however, all major operating systems have implemented full Unicode support and a growing number of applications, including most web browsers, also support Unicode. We therefore believe that encoders should take full advantage of the Unicode Standard, as recommended in ch. 2.2.2 above. As of version 2.0, the character encoding recommended in The Menota handbook has been synchronised with the recommendations by the Medieval Unicode Font Initiative . The character recommendations by MUFI contain more than 1,300 characters in the Latin alphabet of potential use for the encoding of Medieval Nordic texts. As a consequence of the synchronisation, the list of entities which is part of the Menota scheme is identical to the one by MUFI. In other words, if a character is encoded with a code point or an entity in the MUFI character recommendation, it will be a valid character encoding also in a Menota text. -

Characters for Classical Latin

Characters for Classical Latin David J. Perry version 13, 2 July 2020 Introduction The purpose of this document is to identify all characters of interest to those who work with Classical Latin, no matter how rare. Epigraphers will want many of these, but I want to collect any character that is needed in any context. Those that are already available in Unicode will be so identified; those that may be available can be debated; and those that are clearly absent and should be proposed can be proposed; and those that are so rare as to be unencodable will be known. If you have any suggestions for additional characters or reactions to the suggestions made here, please email me at [email protected] . No matter how rare, let’s get all possible characters on this list. Version 6 of this document has been updated to reflect the many characters of interest to Latinists encoded as of Unicode version 13.0. Characters are indicated by their Unicode value, a hexadecimal number, and their name printed IN SMALL CAPITALS. Unicode values may be preceded by U+ to set them off from surrounding text. Combining diacritics are printed over a dotted cir- cle ◌ to show that they are intended to be used over a base character. For more basic information about Unicode, see the website of The Unicode Consortium, http://www.unicode.org/ or my book cited below. Please note that abbreviations constructed with lines above or through existing let- ters are not considered separate characters except in unusual circumstances, nor are the space-saving ligatures found in Latin inscriptions unless they have a unique grammatical or phonemic function (which they normally don’t). -

Special Characters in Aletheia

Special Characters in Aletheia Last Change: 28 May 2014 The following table comprises all special characters which are currently available through the virtual keyboard integrated in Aletheia. The virtual keyboard aids re-keying of historical documents containing characters that are mostly unsupported in other text editing tools (see Figure 1). Figure 1: Text input dialogue with virtual keyboard in Aletheia 1.2 Due to technical reasons, like font definition, Aletheia uses only precomposed characters. If required for other applications the mapping between a precomposed character and the corresponding decomposed character sequence is given in the table as well. When writing to files Aletheia encodes all characters in UTF-8 (variable-length multi-byte representation). Key: Glyph – the icon displayed in the virtual keyboard. Unicode – the actual Unicode character; can be copied and pasted into other applications. Please note that special characters might not be displayed properly if there is no corresponding font installed for the target application. Hex – the hexadecimal code point for the Unicode character Decimal – the decimal code point for the Unicode character Description – a short description of the special character Origin – where this character has been defined Base – the base character of the special character (if applicable), used for sorting Combining Character – combining character(s) to modify the base character (if applicable) Pre-composed Character Decomposed Character (used in Aletheia) (only for reference) Combining Glyph -

Kabbalah, Magic & the Great Work of Self Transformation

KABBALAH, MAGIC AHD THE GREAT WORK Of SELf-TRAHSfORMATIOH A COMPL€T€ COURS€ LYAM THOMAS CHRISTOPHER Llewellyn Publications Woodbury, Minnesota Contents Acknowledgments Vl1 one Though Only a Few Will Rise 1 two The First Steps 15 three The Secret Lineage 35 four Neophyte 57 five That Darkly Splendid World 89 SIX The Mind Born of Matter 129 seven The Liquid Intelligence 175 eight Fuel for the Fire 227 ntne The Portal 267 ten The Work of the Adept 315 Appendix A: The Consecration ofthe Adeptus Wand 331 Appendix B: Suggested Forms ofExercise 345 Endnotes 353 Works Cited 359 Index 363 Acknowledgments The first challenge to appear before the new student of magic is the overwhehning amount of published material from which he must prepare a road map of self-initiation. Without guidance, this is usually impossible. Therefore, lowe my biggest thanks to Peter and Laura Yorke of Ra Horakhty Temple, who provided my first exposure to self-initiation techniques in the Golden Dawn. Their years of expe rience with the Golden Dawn material yielded a structure of carefully selected ex ercises, which their students still use today to bring about a gradual transformation. WIthout such well-prescribed use of the Golden Dawn's techniques, it would have been difficult to make progress in its grade system. The basic structure of the course in this book is built on a foundation of the Golden Dawn's elemental grade system as my teachers passed it on. In particular, it develops further their choice to use the color correspondences of the Four Worlds, a piece of the original Golden Dawn system that very few occultists have recognized as an ini tiatory tool. -

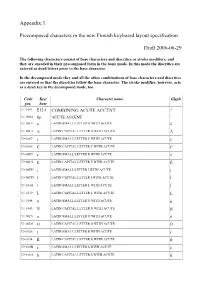

Appendix 3. Precomposed Characters in the New Finnish Keyboard Layout

Appendix 3. Precomposed characters in the new Finnish keyboard layout specification Draft 2006-06-29 The following characters consist of base characters and diacritics or stroke modifiers, and they are encoded in their precomposed form in the basic mode. In this mode the diacritics are entered as dead letters prior to the base character. In the decomposed mode they and all the other combinations of base characters and diacritics are entered so that the diacritics follow the base character. The stroke modifier, however, acts as a dead key in the decomposed mode, too. Code Key/ Character name Glyph pos. base U+0301 E12-1 COMBINING ACUTE ACCENT U+00B4 Sp. ACUTE ACCENT ´ U+00E1 a LATIN SMALL LETTER A WITH ACUTE á U+00C1 A LATIN CAPITAL LETTER A WITH ACUTE Á U+0107 c LATIN SMALL LETTER C WITH ACUTE U+0106 C LATIN CAPITAL LETTER C WITH ACUTE U+00E9 e LATIN SMALL LETTER E WITH ACUTE é U+00C9 E LATIN CAPITAL LETTER E WITH ACUTE É U+00ED i LATIN SMALL LETTER I WITH ACUTE í U+00CD I LATIN CAPITAL LETTER I WITH ACUTE Í U+013A l LATIN SMALL LETTER L WITH ACUTE U+0139 L LATIN CAPITAL LETTER L WITH ACUTE U+0144 n LATIN SMALL LETTER N WITH ACUTE U+0143 N LATIN CAPITAL LETTER N WITH ACUTE U+00F3 o LATIN SMALL LETTER O WITH ACUTE ó U+00D3 O LATIN CAPITAL LETTER O WITH ACUTE Ó U+0155 r LATIN SMALL LETTER R WITH ACUTE U+0154 R LATIN CAPITAL LETTER R WITH ACUTE U+015B s LATIN SMALL LETTER S WITH ACUTE U+015A S LATIN CAPITAL LETTER S WITH ACUTE U+00FA u LATIN SMALL LETTER U WITH ACUTE ú U+00DA U LATIN CAPITAL LETTER U WITH ACUTE Ú U+1E83 w LATIN SMALL LETTER W WITH ACUTE 3 U+1E82 W LATIN CAPITAL LETTER W WITH ACUTE 2 U+00FD y LATIN SMALL LETTER Y WITH ACUTE U+00DD Y LATIN CAPITAL LETTER Y WITH ACUTE U+017A z LATIN SMALL LETTER Z WITH ACUTE # U+0179 Z LATIN CAPITAL LETTER Z WITH ACUTE " U+01FD æ LATIN SMALL LETTER AE WITH ACUTE / U+01FC Æ LATIN CAPITAL LETTER AE WITH ACUTE . -

1 Symbols (2286)

1 Symbols (2286) USV Symbol Macro(s) Description 0009 \textHT <control> 000A \textLF <control> 000D \textCR <control> 0022 ” \textquotedbl QUOTATION MARK 0023 # \texthash NUMBER SIGN \textnumbersign 0024 $ \textdollar DOLLAR SIGN 0025 % \textpercent PERCENT SIGN 0026 & \textampersand AMPERSAND 0027 ’ \textquotesingle APOSTROPHE 0028 ( \textparenleft LEFT PARENTHESIS 0029 ) \textparenright RIGHT PARENTHESIS 002A * \textasteriskcentered ASTERISK 002B + \textMVPlus PLUS SIGN 002C , \textMVComma COMMA 002D - \textMVMinus HYPHEN-MINUS 002E . \textMVPeriod FULL STOP 002F / \textMVDivision SOLIDUS 0030 0 \textMVZero DIGIT ZERO 0031 1 \textMVOne DIGIT ONE 0032 2 \textMVTwo DIGIT TWO 0033 3 \textMVThree DIGIT THREE 0034 4 \textMVFour DIGIT FOUR 0035 5 \textMVFive DIGIT FIVE 0036 6 \textMVSix DIGIT SIX 0037 7 \textMVSeven DIGIT SEVEN 0038 8 \textMVEight DIGIT EIGHT 0039 9 \textMVNine DIGIT NINE 003C < \textless LESS-THAN SIGN 003D = \textequals EQUALS SIGN 003E > \textgreater GREATER-THAN SIGN 0040 @ \textMVAt COMMERCIAL AT 005C \ \textbackslash REVERSE SOLIDUS 005E ^ \textasciicircum CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT 005F _ \textunderscore LOW LINE 0060 ‘ \textasciigrave GRAVE ACCENT 0067 g \textg LATIN SMALL LETTER G 007B { \textbraceleft LEFT CURLY BRACKET 007C | \textbar VERTICAL LINE 007D } \textbraceright RIGHT CURLY BRACKET 007E ~ \textasciitilde TILDE 00A0 \nobreakspace NO-BREAK SPACE 00A1 ¡ \textexclamdown INVERTED EXCLAMATION MARK 00A2 ¢ \textcent CENT SIGN 00A3 £ \textsterling POUND SIGN 00A4 ¤ \textcurrency CURRENCY SIGN 00A5 ¥ \textyen YEN SIGN 00A6 -

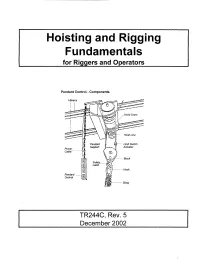

Hoisting & Rigging Fundamentals

Hoisting and Rigging Fundamentals for Riaaers and ODerators Pendant Control - Components TR244C, Rev. 5 December 2002 TR244C Rev . 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................ ii HOISTING AND RIGGING OBJECTIVES ......................................... 1 WIRE ROPE SLINGS ......................................................... 2 SYNTHETIC WEBBING SLINGS ............................................... IO CHAINSLINGS ............................................................ 14 METAL MESH SLINGS ...................................................... 18 SPREADER BEAMS ........................................................ 19 RIGGING HARDWARE ...................................................... 22 INSPECTION TAG .......................................................... 39 CRITICAL LIFTS ........................................................... 40 GENERAL HOISTING AND RIGGING PRACTICES ................................ 44 HANDSIGNALS ............................................................ 64 INCIDENTAL HOISTING OPERATOR OBJECTIVES ............................... 68 HOISTS .................................................................. 69 OVERHEAD AND GANTRY CRANES ........................................... 71 MOBILECRANES .......................................................... 77 APPENDIX ................................................................ 81 TC:0007224.01 i TR244C Rev. 5 INTRODUCTION HOISTING AND RIGGING PROGRAM Safety should be the first priority when performing -

No. 447,618, Patented Mar, 3, 189L

(No Model.) J. K. MILLER, ROPE HOOK. No. 447,618, Patented Mar, 3, 189l. INVENTOR: -6. ATTORNEYS UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE. JAMES K. MILLER, OF EMPORIA, KANSAS, RO PE HOOK. SPECIFICATION forming part of Letters Patent No. 447,618, dated March 3, 1891. Application filed May 17, 1890, Serial No. 352,246, (No model.) To all, whon it indi/ concern: through the upper hook A, and one or more 55 Be it known that I, JAMES K. MILLER, of turns around the shank between hook A and Emporia, in the county of Lyon and State of the lower hooks A, the free end C of the rope Kansas, have invented a new and Improved C being allowed to dangle from the hook, as Rope-Hook, of which the following is a full, shown. clear, and exact description. While I have shown a particular means for My invention relates to improvements in fastening the rope C in the hook, it is evi rope-hooks; and the object of the invention is dent that it may be fastened in a great many to provide a hook that is suitable for use with ways, so as either to hold the rope in a sta O clothes-lines, hammocks, for hoisting pur tionary position or to allow it to slide slowly poses, or for fastening bundles, and various through the hook. other purposes, and one by which a rope may It will be seen that by having the two hooks be easily and quickly fastened. A upon opposite sides of the shank the rope To this end my invention consists in a hook C may be passed through either of said hooks, having a single shank and a terminal eye, and may be passed through the central hook and having two oppositely-extending hooks A from either the right hand or the left with at its lower end, and a central hook above equal facility, so that an unskilled person said lower hooks and at right angles to the will have no difficulty in securing the rope to SO, the hook. -

The Brill Typeface User Guide & Complete List of Characters

The Brill Typeface User Guide & Complete List of Characters Version 2.06, October 31, 2014 Pim Rietbroek Preamble Few typefaces – if any – allow the user to access every Latin character, every IPA character, every diacritic, and to have these combine in a typographically satisfactory manner, in a range of styles (roman, italic, and more); even fewer add full support for Greek, both modern and ancient, with specialised characters that papyrologists and epigraphers need; not to mention coverage of the Slavic languages in the Cyrillic range. The Brill typeface aims to do just that, and to be a tool for all scholars in the humanities; for Brill’s authors and editors; for Brill’s staff and service providers; and finally, for anyone in need of this tool, as long as it is not used for any commercial gain.* There are several fonts in different styles, each of which has the same set of characters as all the others. The Unicode Standard is rigorously adhered to: there is no dependence on the Private Use Area (PUA), as it happens frequently in other fonts with regard to characters carrying rare diacritics or combinations of diacritics. Instead, all alphabetic characters can carry any diacritic or combination of diacritics, even stacked, with automatic correct positioning. This is made possible by the inclusion of all of Unicode’s combining characters and by the application of extensive OpenType Glyph Positioning programming. Credits The Brill fonts are an original design by John Hudson of Tiro Typeworks. Alice Savoie contributed to Brill bold and bold italic. The black-letter (‘Fraktur’) range of characters was made by Karsten Lücke. -

Smsolar Mount

SOLAR SM MOUNT INSTALLATION GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS A - PRO SERIES SYSTEM COMPONENTS O - BONDING CONNECTION GROUND PATHS B - SYSTEM LAYOUT P – TRIM AND END CAP INSTALLATION C - CODE COMPLIANCE NOTES Q – STANDARD SYSTEM COMPONENTS D - ROOF ATTACHMENT & L-FEET E - SPLICE & THERMAL BREAK R –MODULE CAPABILITY F - ATTACH RAIL TO L-FEET S – ATTACH RAIL TO L-FEET G - MICROINVERTER MOUNTING T – ENDCLAMP & FIRST MODULE H - MICROINVERTER SYSTEM GROUNDING U –BONDING MIDCLAMP & TRIM I - ELECTRICAL GROUNDING W/ ENPHASE MICRINVERTER FOR V- REMAINING MODULES & TRIM SPLICE & THERMAL BREAK W – TRIM RETROFIT INSTALLATION J - STANDARD SYSTEM GROUNDING X – BONDING CONNECTION GROUND PATHS K - END CLAMP, FIRST MODULE L- BONDING MID CLAMP Y – BONDING CONNECTION GROUND PATHS M - REMAINING MODULES APPENDIX A : SYSTEM CERTIFICATION N - BONDING CONNECTION GROUND PATHS APPENDIX B: FLASHKIT PRO INSTALLATION PUB2020JAN07 SOLAR PRO SERIES SYSTEM COMPONENTS A SM MOUNT INSTALLATION GUIDE PAGE RAIL: Supports PV modules. Use at least two per row of modules. Aluminum extrusion, available in mill, clear anodized, or dark anodized. RAIL SPLICE: Non structural splice joins, aligns, and electrically bonds rail sections into single length of rail. Forms a rigid splice joint, 4 inches long, preassembled with bonding hardware. Available in dark anodized or mill finish. L-FOOT: Use to secure rails through roofing material to building structure. Refer to loading tables or U-Builder for spacing. L-FOOT T- BOLT: (3/8” x ¾" or 1”) – Use one per L-foot to secure rail to L-foot. Stainless steel. Supplied with L-foot in combination with flange nut, provides electrical bond between L-foot and rail.