A Thumbnail History of the Nelson Forest Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

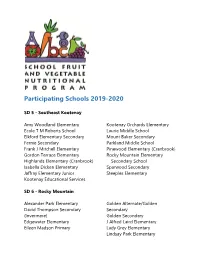

Participating Schools 2019-2020

Participating Schools 2019-2020 SD 5 - Southeast Kootenay Amy Woodland Elementary Kootenay Orchards Elementary Ecole T M Roberts School Laurie Middle School Elkford Elementary Secondary Mount Baker Secondary Fernie Secondary Parkland Middle School Frank J Mitchell Elementary Pinewood Elementary (Cranbrook) Gordon Terrace Elementary Rocky Mountain Elementary Highlands Elementary (Cranbrook) Secondary School Isabella Dicken Elementary Sparwood Secondary Jaffray Elementary Junior Steeples Elementary Kootenay Educational Services SD 6 - Rocky Mountain Alexander Park Elementary Golden Alternate/Golden David Thompson Secondary Secondary (Invermere) Golden Secondary Edgewater Elementary J Alfred Laird Elementary Eileen Madson Primary Lady Grey Elementary Lindsay Park Elementary Martin Morigeau Elementary Open Doors Alternate Education Marysville Elementary Selkirk Secondary McKim Middle School Windermere Elementary Nicholson Elementary SD 8 - Kootenay Lake Adam Robertson Elementary Mount Sentinel Secondary Blewett Elementary School Prince Charles Brent Kennedy Elementary Secondary/Wildflower Program Canyon-Lister Elementary Redfish Elementary School Crawford Bay Elem-Secondary Rosemont Elementary Creston Homelinks/Strong Start Salmo Elementary Erickson Elementary Salmo Secondary Hume Elementary School South Nelson Elementary J V Humphries Trafalgar Middle School Elementary/Secondary W E Graham Community School Jewett Elementary Wildflower School L V Rogers Secondary Winlaw Elementary School SD 10 - Arrow Lakes Burton Elementary School Edgewood -

Landslides Along the Columbia River Valley Northeastern Washington

Landslides Along the Columbia River Valley Northeastern Washington GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 367 Landslides Along the Columbia River Valley Northeastern Washington By FRED O. JONES, DANIEL R. EMBODY, and WARREN L. PETERSON With a section on Seismic Surveys By ROBERT M. HAZLEWOOD GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 367 Descriptions of landslides and statistical analyses of data on some 2OO landslides in Pleistocene sediments UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1961 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director The U.S. 'Geological Survey Library has cataloged this publication as follows : Jones, Fred Oscar, 1912- Landslides along the Columbia River valley, northeastern Washington, by Fred O. Jones, Daniel R. Embody, and Warren L. Peterson. With a section on Seismic surveys, by Robert M. Hazlewood. Washington, U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1961. v, 98 p. illus., maps (part col.) diagrs., tables. 30 cm. (U.S. Geological Survey. Professional paper 367) Part of illustrative matter in pocket. Bibliography: p. 94-95. 1. Landslides Washington (State) Columbia River valley. 2. Seismology Washington (State) I. Embody, Daniel R., joint author. II. Peterson, Warren Lee, 1925- , joint author. III. Hazle wood, Robert Merton, 1920-IV. Title. (Series) For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, B.C. CONTENTS Page Statistical studies Continued Abstract _ ________________________________________ 1 Statistical analyses, by Daniel R. Embody and Fred Introduction, by Fred O. Jones___________ ____________ 1 O.Jones _-_-_-_-____-__-___-_-_-- _ _____--- 46 Regional physiographic and geologic setting________ 3 Analysis and interpretation of landslide data_-_ 46 Cultural developments. -

2018 General Local Elections

LOCAL ELECTIONS CAMPAIGN FINANCING CANDIDATES 2018 General Local Elections JURISDICTION ELECTION AREA OFFICE EXPENSE LIMIT CANDIDATE NAME FINANCIAL AGENT NAME FINANCIAL AGENT MAILING ADDRESS 100 Mile House 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Wally Bramsleven Wally Bramsleven 5538 Park Dr 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E1 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Leon Chretien Leon Chretien 6761 McMillan Rd Lone Butte, BC V0K 1X3 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Ralph Fossum Ralph Fossum 5648-103 Mile Lake Rd 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E1 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Laura Laing Laura Laing 6298 Doman Rd Lone Butte, BC V0K 1X3 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Cameron McSorley Cameron McSorley 4481 Chuckwagon Tr PO Box 318 Forest Grove, BC V0K 1M0 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 David Mingo David Mingo 6514 Hwy 24 Lone Butte, BC V0K 1X1 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Chris Pettman Chris Pettman PO Box 1352 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E0 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Maureen Pinkney Maureen Pinkney PO Box 735 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E0 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Nicole Weir Nicole Weir PO Box 545 108 Mile Ranch, BC V0K 2Z0 100 Mile House Mayor $10,000.00 Mitch Campsall Heather Campsall PO Box 865 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E0 100 Mile House Mayor $10,000.00 Rita Giesbrecht William Robertson 913 Jens St PO Box 494 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E0 100 Mile House Mayor $10,000.00 Glen Macdonald Glen Macdonald 6007 Walnut Rd 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E3 Abbotsford Abbotsford Councillor $43,928.56 Jaspreet Anand Jaspreet Anand 2941 Southern Cres Abbotsford, BC V2T 5H8 Abbotsford Councillor $43,928.56 Bruce Banman Bruce Banman 34129 Heather Dr Abbotsford, BC V2S 1G6 Abbotsford Councillor $43,928.56 Les Barkman Les Barkman 3672 Fife Pl Abbotsford, BC V2S 7A8 This information was collected under the authority of the Local Elections Campaign Financing Act and the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act. -

Investment Package

Hello!! Castlegar’s location squarely in the middle of Vancouver and Calgary has produced today’s investment opportunity. Castlegar’s competitive advantage lies in its central location, low business costs/cost of living, and outdoor lifestyle. The West Kootenay has a distinct cultural flavour and warmth of humanity that will bring a quick smile to your face… and a lingering feeling of contentment. Lifestyle is not urban rush, but a relaxed mix of outdoor rugged and urban cool. There is a creative undertow to the human tide. Business is important, but the lifestyle dog still wags the business tail. Situated midway between Vancouver and Calgary, the West Kootenay has received less Vancouver/Calgary region investment than the Okanagan and the East Kootenay. This creates a business opportunity and an affordable cost of living that supports the notion that entrepreneurs can both balance the books and balance life. Castlegar’s economic base is stable and diversified (forestry, mining, hydro, government services, retail, tourism). Business conditions are dynamic and affordable. The City is big enough to support full services. But Castlegar knows it can do more and its service centre vision is ambitious. Diversification has two key thrusts: commercial and light industry anchors (we affectionately call this the ‘Big Kahuna Strategy’), and independent entrepreneurs (we affectionately call this the ‘Dilbert Escape’ strategy). www.castlegar.ca happily ever after MAYOR’S LETTER Welcome to Castlegar and the West Kootenay. Having been born and raised in the Castlegar area, it’s easy for me to extol the virtues of Castlegar living. I would prefer to tell you about Castlegar through the eyes of newcomers and Valley explorers I talk to – those who see our culture and geography as tourists, or potential future residents and/or investors. -

$ Take a Pointer^" COAL

<A VICTORIA, B.C., THURSDAY, OCTOB! Vol. 26. 14, 1897. No. 33, -C--...................; mvsmi £ Marriage 1HE GRAND TRUNK TRAINS COLLIDE / A Fine New Lot of our Fall Goods. No Failure. OUT CLASS AND STERLING SILVER Somi, Annual Meet.ng of Stock NEAR OHAWA TAMII.KANDK ! TAMILKANE>R ! Uw p,tie of Ceiyon. holder!-A Sarplna of The fragrance of thy leave* in both hotelapbere» are known, •1Î.OOO Shown. Tbe Heweet, tiivt-» hawHue»* to million*—*et» the tired heart free, Three Men Killed and Several Severe Brushes, Combs, And Mods tbe laurel wreath around TAMILKAXDE TEA. Tbe Best end ly Injured-An Operator at Fanlt. Tbe Cheapest And a# kind» of Manicure Within th.' lowly cotta# The President Attribute!the Improve and Toilet Sets. Uive* courage in life’s battle uhem-v« r duty caiia. ment to Mere. Economic»! RHirrors IL juv. nat. - iry hours Management, Etc. la the struggle for exiettoK'e iu ihtw ‘ t'nnada of onrs.° Grenier, the Libeller of Mr. Tarte. All hail. TAMILKAXDE 1 he « very leaf and. vine. Sentenced to Six Months ppMiWpA'.-.. That make* thk life worth living in this qr any clime, I Challoner, tyitchell & Co. I”' COVERNMIKT ST ikondon, Oet. 14.—The annual meeting Proves marriage no feilnn dispntn! though It be— ot the atockholdera of the tirund Trunk S - -;-g^fc«ri4.i^'S4,ttL»/St«^S^ÂÏk»>*/E^iE^»»Sâ If supplied with a pound of TAiiil.K railway or Canada wa* held today. The attendance uw large and har- Ottawa, Oct.14.—There was a coUiaion •fi sRrw'i,T55ki-v>c |irv*klent oT the n>ad, congru tulatv.T thé Tonmto ran Into a fn-igbi. -

Rossland OCP Background Study 2021-03-05

BACKGROUND AND KEY ISSUES REPORT February 2021 Background and Key Issues Report February 2021 Official Community Plan Update This report provides a summary of the information that has been collected to date that will inform the ongoing update to the City of Rossland’s Official Community Plan. There are three main sections in this report: A summary of the Project Initiation, Background Review and Key Issues and a Technical Review. Project Initiation will briefly summarize tasks completed as part of Phase 1 and provide a Community Snapshot of Rossland. The Background Review and Key Issues section will assess the current planning and technical documents that have been in effect since 2007 and identify the gaps and key issues that will inform the OCP update. Section 3 provides a more comprehensive policy and technical review on climate resiliency, transportation and infrastructure. A report on food security in Rossland is included in the Appendix. This background information will inform and help to frame the next stages of the OCP update. If you have any questions about this report or would like to provide additional feedback, please email us at [email protected] or visit https://rossland.city/ocp-update for more information. 1 Contents Official Community Plan Update ..................................................................................... 1 1 Review Process ...................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Where Are We in the Process? ..................................................................................... -

Order in Council 2560/1959

2560. Approved and ordered this 12th day of November , A.c. 1959. At the Executive Council Chamber, Victoria, uienani-Governor. PRESENT: The Honourable in the Chair. Mr. Bennett Mr. Wick! Mr. Black Mr. Bonner Mr. Williston Mr. Peterson Mr. Mertir Mr. Chant Mr. Westwood Mr. paC Mr. To His Honour The Lieutenant-Governor in Council: The undersigned has the honour to recommend: THAT Order-in-Council No. 2402/ dated the 22nd day of October 1959 be amended by adding immediately after the words "attached hereto" at the end of the fifth line, the following:- ", and by striking out Regulation 19.03 and substituting Regulation 19.03 in the form attached" Dated this /14- day of n01;141-4/A.D. 1959 Minister of Commercial Transport Approved this / Litt day of ihri)j2"44-11.D. 1959 Presiding Member of the Executive Council. SCHEDULE I. - HIGHWAYS (1) King George VI Highway (Route No. 99) from its intersection with the Trans-Canada Highway to the International Boundary at Douglas. (2) Trans-Canada Highway (Route No. 1) from the south end of Lions Gate Bridge to Horseshoe Bay. (3) Trans-Canada Highway (Route No. 1) from the west boundary of Burnaby Municipality to the east boundary of Burnaby Municipality and from the east boundary of the City of New Westminster to Spuzzum. (4) The Lougheed Highway (Route No. 7) from the west boundary of Burnaby Municipality to Agassiz. (5) The Southern Trans-Provincial Highway (Route No. 3) from Hope to the junction with Route No. 395 at Christina Lake, and from Rossland to Trail, and from Kuskanook to the British Columbia boundary at Crowsnest. -

Galena Shelter Ferries Increase Service Until Thanksgiving

July 17, 2008 The Valley Voice 1 Volume 17, Number 14 July 17, 2008 Delivered to every home between Edgewood, Kaslo & South Slocan. Published bi-weekly. “Your independently owned regional community newspaper serving the Arrow Lakes, Slocan & North Kootenay Lake Valleys.” Windstorm causes power outages in Arrow Lakes and Slocan Valleys by Jan McMurray worked into the night on July 10 (snowstorm in April, mudslide in they could then replace the cables. He the club to call in the divers soon for On July 10, a windstorm hit the on the main lines and then tackled May and windstorm in July) and says there are enough anchors to hold an assessment. Fortunately, no boats Arrow Lakes and Slocan Valleys, the smaller distribution lines on the one in March was caused by a the structure temporarily, and expects were damaged. causing extended power outages as July 11. failed insulator. Because of the more several trees and other debris came The power went out for BC frequent and extended outages due down onto power lines. The storm Hydro customers from Needles to to severe weather since 2006, BC swept through on its way from Silverton at about 2:45 pm July Hydro has launched a new power the Okanagan right down to the 10 when two power poles in the outage communication initiative. Boundary area. Brouse Loop area came down on the As part of this initiative, BC Hydro In the Slocan Valley, the power main transmission line. Power was representatives will be meeting was out from early afternoon to about restored for most customers between with key representatives from the midnight on July 10 for most people, Needles and Nakusp at about 5:20 communities it serves. -

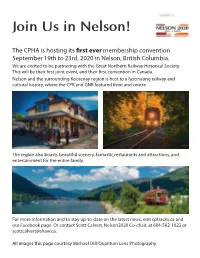

Join Us in Nelson!

Join Us in Nelson! The CPHA is hosting its first ever membership convention September 19th to 23rd, 2020 in Nelson, British Columbia. We are excited to be partnering with the Great Northern Railway Historical Society. This will be their first joint event, and their first convention in Canada. Nelson and the surrounding Kootenay region is host to a fascinating railway and cultural history, where the CPR and GNR featured front and centre. The region also boasts beautiful scenery, fantastic restaurants and attractions, and entertainment for the entire family. For more information and to stay up-to-date on the latest news, visit cptracks.ca and our Facebook page. Or contact Scott Calvert, Nelson2020 Co-chair, at 604-562-1022 or [email protected]. All images this page courtesy Michael Dill/Quantum Lens Photography. REGISTRATION Complete the registration form included in this mailing of CP TRACKS, or visit our registration page online at cptracks.ca/ nelson2020. *NOTE: Space is limited on some tours by bus or venue capacity. Registrations will be treated on a first come, first served basis so register early! Included with registration: Friday evening “Meet and Greet” Nelson Heritage Tram rides Heritage Tram shop tour with CPR 8605 eases its train off of the barge at Slocan City. Rail-marine operations were a distinctive feature of Kootenay railroading. wine and cheese reception Mark Horne photo All Clinics Models and Photo Display room access Convention Mug HOTEL The Prestige Lakeside Resort and Convention Prestige Lakeside Resort Centre is our host for the week and the centre Telephone 250.352.7222 of all activities and tours. -

Item Call to Order 2 Public Input Period Committee

THE CORPORATION OF THE CITY OF ROSSLAND AGENDA- COMMITTEE-OF·THE-WHOLE Monday, February 27, 2012 5:30PM Council Chambers City Hall Continuation for the Feb 20.12 COW ITEM SUBJECT MATTER RECOMMENDATION 1 CALL TO ORDER Call to Order Call Meeting to Order 2 PUBLIC INPUT PERIOD 3 COMMITTEE MEETING February 27, 2012 Agenda Adopt Agenda AGENDA 4 OPERATIONAL DISCUSSIONS & PRESENTATIONS BY STAFF c) CAO I Manager of Finance I Review of Draft Financial Plan - Committee recommends to Council for Staff Operating Funds. approval of the Financial Plan 2012- 2016: General Water and Sewer Operating Accounts with amendments as may be required and Staff to prepare the approving bylaws. d) CAO I Manager of Finance I Review of Capital and Committee recommends to Council for Staff Infrastructure Plan approval, with amendments, the Capital and Infrastructure Plan for 2012-2016 and Staff to prepare the approving bylaws. e) CAO I Manager of Finance I Property Taxation Preliminary Committee receive the preliminary Staff Review report. f) CAO I Manager of Finance I Property Taxation for 2012 Staff recommend that the 2012 Staff property taxation remain at the 2011 levels subject to new construction and any amendments that arise from expenditure and revenue changes. g) CAO I Manager of Finance I Population Projections Staff recommend no change to any Staff projections and follow the general guidelines as per the presentation. 5 ADJOURNMENT 1 of 164 THE CORPORATION OF THE CITY OF ROSSLAND AGENDA- REGULAR MEETING Monday, February 27, 2012 7:00PM Council Chambers City Hall SUBJECT MATTER RECOMMENDATION 1 CALL TO ORDER Call to Order Call Meeting to Order 2 PUBLIC INPUT PERIOD 3 REGULAR MEETING AGENDA February 27, 2012 Agenda Adopt Agenda 4 MINUTES a) February 13, 2012 Regular Meeting Minutes Adopt Minutes a) February 13, 2012 Record of Public Hearing - Bylaw Adopt Minutes 2523 5 REGISTERED PETITIONS AND DELEGATIONS a) Kootenay Rockies Tourism Power point presentation. -

West Kootenay Wildcats Greater Trail Minor Hockey Association Trail, Bc

2019 PEE WEE FEMALE BC HOCKEY CHAMPIONSHIPS March 20-24, 2019 HOSTED BY: WEST KOOTENAY WILDCATS GREATER TRAIL MINOR HOCKEY ASSOCIATION TRAIL, BC 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTACT INFORMATION Page 3 • HOST ASSOCIATION • GTMHA COMMITTEE • BC HOCKEY REPRESENTATIVE BC HOCKEY CHAMPIONSHIPS INFORMATION Page 4 • DATE OF CHAMPIONSHIP • BANQUET INFORMATION • OFFICIALS / COACHES / MANAGERS MEETING • OPENING/CLOSING CEREMONIES • PRIZE TABLE ARENA AND MAP Page 5-6 MEDICAL FACILITIES Page 6 TEAM SERVICES Page 7 THINGS TO DO Pages 7-8 TRANSPORTATION ROUTES Page 8 WEST KOOTENAY ADDITIONAL INFORMATION Page 9 MAP OF TRAIL Page 9 WEST KOOTENAY INFORMATION Pages 10-14 HOTEL ACCOMMODATIONS Pages 15-16 RESTAURANTS Page 17 2 Greater Trail Minor Hockey Association Trail Memorial Centre 1051 Victoria Avenue Trail, BC (250) 364 – 0888 (250) 368 - 6484 HOST COMMITTEE CHAIRS Mark Buckley Cell: (250) 368-7279 Email: [email protected] Clare DeWitt Cell: (250) 231-7496 Email: [email protected] Michael Conci Cell: (250) 231–6453 Email: [email protected] BC Hockey Championships Contact Sean Orr, Senior Manager, Leagues & Events BC Hockey [email protected] 250.652.2978 3 BC HOCKEY CHAMPIONSHIP INFORMATION The 2019 PEE WEE FEMALE BC Hockey Championships will commence on Wed. March 20 th with a Team Banquet and Coaches Meeting. The tournament games will start Thursday March 21st ending with the Championship Game on Sunday, March 24 th , 2019. Games will be held at the Trail Memorial Centre: located at 1051 Victoria Avenue, Trail, BC. Due to possible conflicts with Junior hockey playoffs, some games may have to be played at a different arena in the association. -

2021-04-15 Board Addenda

Regional District of Central Kootenay REGULAR BOARD MEETING Open Meeting Revised Date: Thursday, April 15, 2021 Time: 9:00 am Location: RDCK Remote Meeting The meeting is held remotely due to COVID-19 Directors will have the opportunity to participate in the meeting electronically. Proceedings are open to the public. Pages 1. CALL TO ORDER & WELCOME 1.1. TRADITIONAL LANDS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT STATEMENT We acknowledge and respect the indigenous peoples within whose traditional lands we are meeting today. 1.2. ADOPTION OF THE AGENDA RECOMMENDATION: (ALL VOTE) The agenda for the April 15, 2021 Regular Open Board meeting be adopted with the following amendments: • inclusion of Item 3.1.5 Central Resource Recovery Committee: minutes April 14, 2021; • inclusion of Item 3.2.3 Area A Economic Development Commission: minutes April 7, 2021; • inclusion of Item 8.2.4 Rosebud Lake: Planned Logging in the Community Watershed; and • with the addition of the addendum before circulation. 1.3. ADOPTION OF THE MINUTES 23 - 49 RECOMMENDATION: (ALL VOTE) The minutes from the March 18, 2021 Regular Open Board meeting be adopted as circulated. 1.4. DELEGATIONS 1.4.1. West Kootenay Boundary Community Investment Co-op 50 - 54 Tyler Rice Treasurer 1.4.2. Community Futures Central Kootenay 55 - 76 Andrea Wilkey Executive Director 2. BUSINESS ARISING OUT OF THE MINUTES 2.1. Director Davidoff: Area H and I Cell Service Infrastructure and Leasing Joint Service Feasibility Study Board Meeting - January 21, 2021 RES 65/21 That the following recommendation BE REFERRED to the February 18, 2021 Board meeting: That the Board approve up to $30,000 in the 2021 Financial Plan from the S106 Feasibility Study Reserve to hire a consultant to determine requirements and a proposed scope for the RDCK to assist telecommunications service providers in expanding cellular service in Electoral Areas I and H.