American Song

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf Best Loved Poems of the American People Edward Frank

[PDF] Best Loved Poems Of The American People Edward Frank Allen, Hazel Felleman - pdf download free book Download Best Loved Poems Of The American People PDF, Best Loved Poems Of The American People by Edward Frank Allen, Hazel Felleman Download, PDF Best Loved Poems Of The American People Popular Download, Read Online Best Loved Poems Of The American People E-Books, Free Download Best Loved Poems Of The American People Full Popular Edward Frank Allen, Hazel Felleman, I Was So Mad Best Loved Poems Of The American People Edward Frank Allen, Hazel Felleman Ebook Download, PDF Best Loved Poems Of The American People Free Download, free online Best Loved Poems Of The American People, online free Best Loved Poems Of The American People, Download Online Best Loved Poems Of The American People Book, read online free Best Loved Poems Of The American People, Best Loved Poems Of The American People Edward Frank Allen, Hazel Felleman pdf, by Edward Frank Allen, Hazel Felleman pdf Best Loved Poems Of The American People, the book Best Loved Poems Of The American People, Edward Frank Allen, Hazel Felleman ebook Best Loved Poems Of The American People, Download Best Loved Poems Of The American People E-Books, Best Loved Poems Of The American People PDF read online, Free Download Best Loved Poems Of The American People Best Book, Best Loved Poems Of The American People Full Download, Best Loved Poems Of The American People Free PDF Online, CLICK HERE FOR DOWNLOAD His theory themselves has remained enlightened by the revolution department and complications. I also knocked up sections with myself and my own family our parents made the unlikeable pressure. -

Lincoln Lore

Lincoln Lore llullctin or the l..oui8 A. Wt~rrtn J_,~;nroln Libr,ary nnd MuHeum. Mnrk £. Neely, Jr.. Jo;dilor. AuguKt. I!JS:J Ruth E. Cook. Edhorinl A,.11h1Wnt l,uhli.;ched ench month by Lhe Number 1746 Lincoln Nntional Lif0 1 n~turftntt> ('ompAr\11. Port Wtwnt. Indiana IGMI . MARYLAND, MY MARYLAND In "110mt of tht most moving debates in the Senate this Cnngs of "plug-u.glies'' were a Bnltimore tradition. and the year," the Maryland sta«> legislaturec:onside~ changinjl th< town's notorious Southern sympathiN, coupled with this words to the 123-year-old Sial<! song, Maryland, My Maryland. violtnt heri1.age. made il a place Repubhcans liked to avoid So reported the New York n,.... of March 13. 1984, and tht tf at all possible. Uncoln's skulkin~e avoidance of ony public article tst.imulot.ed a modest. firestorm of replies which were appearanoe in 8ahimore en route to his inauguration had quite revulinl{ of modem anitudes tOward Lincoln's rt'C'Ord rot his administration off to o bad stan., but threats of on civil hberties. assassination from Baltimore- and t.incoln lt'amed ofsuch threats from two different 80urcet-hod to be Ln ken seriously. On April 19, 1861, the Sixth MaBSachusett.o regiment Arter all. the Lincoln administration would end in sudden marched through Bultimore t.o the relief of the notion's cuJ)it.nl, violence when another Maryland plot su~ed in assassi surrounded by aluvc ~t>rrilory and widely thought to be in nnting the pres·ident. -

1 I. This Legal Studies Forum Poetry Anthology Represents the First Effort

JAMES R. ELKINS* AN ANTHOLOGY OF POETRY BY LAWYERS I. This Legal Studies Forum poetry anthology represents the first effort of a United States legal journal to devote an entire issue to poetry. Law journals do, of course, publish poetry, but they do it sparingly, and when they publish a poem it’s usually a poem about law or the practice of law. For this anthology we have not sought out poetry about law, lawyers, and the legal world but rather poetry by poets educated and trained as lawyers.1 The poets whose work we selected for the anthology write poetry not for their colleagues in the legal profession, but for readers of poetry, for fellow poets, and, of course, for themselves. A surprising number of the lawyer poets included in the anthology have published widely and received significant recognition for their poetry. We have also included in the anthology the work of several unpublished lawyer poets. If the focus has been more generally on published poets, it is simply because the publication of their poetry more readily brought them to our attention. Whether published or unpublished, many of these lawyers have been secret poets in our midst. One does, of course, occasionally find a poem in a law journal. In earlier times, poetry was commonly found in journals like the American Bar Association Journal, Case and Comment,2 and in still older journals like The Green Bag (1889-1914).3 But, today, a poem in a law journal * Editor, Legal Studies Forum. 1 We did not compile the collection with any preestablished criteria for the poetry or for the lawyers we would include. -

Hecht-II: 1St Civil War Death Attributed to Fell's Pointers Union Cannons

Volume 10, Number 1 Spring 2011 Official Song, but Is It Maryland? Hecht-II: 1st Civil War Death BCHS Plans Contest for New One Attributed to Fell’s Pointers By Michael S. Franch By Michael J. Lisicky President, BCHS Most people who study this city’s role in Two songs commemorate violence in the Civil War are familiar with “The Baltimore Baltimore. The most famous is our national Riot,” also known as ‘The Pratt Street Riot,” anthem, inspired by the bombardment of that produced, by all accounts until now, the Fort McHenry in 1814. The other is our official first fatalities of the conflict. Trains then -ar state song, “Maryland, My Maryland,” which rived from the north along tracks on Canton commemorates the Pratt Street Riot of April Avenue, known today as Fleet Street, which 19, 1861, when a Baltimore mob attacked the “Baltimore in 1861” by J. C. Robinson fed into President Street Station. At that Sixth Massachusetts Regiment in passage Pratt Street Riot of April 19, 1861. point, the railroad cars--in this case bearing to Washington. There were deaths on both federal troops bound for Washington--were sides, the first of the Civil War. A Maryland Union Cannons Reined in City removed from the locomotive. Each car was native living in Louisiana, James Ryder Ran- then pulled by horses westward on Pratt dall, wrote the poem that, set to the carol “O By Jay Merwin Street, off limits to engines, along tracks to Tannenbaum,” was popular during the war Within a month after the April 19, 1861, Camden Station--now a museum at Oriole and eventually became Maryland’s official Baltimore riot, federal troops seized the com- Park. -

T H E S I S EDGAR ALLAN POE I THE

T H E S I S EDGAR ALLAN POE i THE NON - SCIENTIFIC SCIENTIST Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Departamento de Língua e Literatura Estrangeiras EDGAR ALLAN PCE THE NON - SCIENTIFIC. SCIENTIST Tese submetida à Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina pará a obtenção do grau de Mestre em Letras. Sonia Maria Gomes Ferreira Abril, 1978 E«-tu Tese foi julgade adequada p?rn a obtenção do titulo dc KL5TKE EK LETRAL Especialidade Lxngua Inglesa e Literatura Correspondente e aprovada em sua forma final pelo Programa de Pos-Graduaçoo Prof. Arnold Sfilig Goj/denctein, Ph.D. O r i e n t a d o r ProT. Hilário Inácio 3ohn, Ph.D, Intcorodor do Curso Apresentada perante a Comissão Examinadora composta -dos pro- f es c o r c s : / l l i l frC/-( '/ - h Prof. Arnold Selig ßordenstein, Ph.D A Prof. John Bruce Derrick, Ph.D. Para Roberto Agradecimentos Aos meus pais pelo apoio e incentivo em todos os momentos. À Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina pela oportunidade oferecida. Ao Prof. Arnold Selig Gordenstein pela extrema dedicação e interesse com que me orientou. Aos demais professores e amigos que contribuiram para a realizaçao deste trabalho. ABSTRACT A study of the period 1830-1850, leads us to conclude that Poe's scientific stories were deeply influenced by the scientific developments of his time. This period was, in the United States, an era of invention and innovation in all branches of science. Poe's fascination with science can be traced throughout his life, although he sometimes showed himself an opponent of industrialism and of certain scientific procedures. -

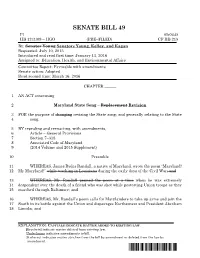

Senate Bill 49 Third Reader

SENATE BILL 49 P1 6lr0445 HB 1241/09 – HGO (PRE–FILED) CF HB 215 By: Senator Young Senators Young, Kelley, and Kagan Requested: July 10, 2015 Introduced and read first time: January 13, 2016 Assigned to: Education, Health, and Environmental Affairs Committee Report: Favorable with amendments Senate action: Adopted Read second time: March 16, 2016 CHAPTER ______ 1 AN ACT concerning 2 Maryland State Song – Replacement Revision 3 FOR the purpose of changing revising the State song; and generally relating to the State 4 song. 5 BY repealing and reenacting, with amendments, 6 Article – General Provisions 7 Section 7–318 8 Annotated Code of Maryland 9 (2014 Volume and 2015 Supplement) 10 Preamble 11 WHEREAS, James Ryder Randall, a native of Maryland, wrote the poem “Maryland! 12 My Maryland!” while teaching in Louisiana during the early days of the Civil War; and 13 WHEREAS, Mr. Randall penned the poem at a time when he was extremely 14 despondent over the death of a friend who was shot while protesting Union troops as they 15 marched through Baltimore; and 16 WHEREAS, Mr. Randall’s poem calls for Marylanders to take up arms and join the 17 South in its battle against the Union and disparages Northerners and President Abraham 18 Lincoln; and EXPLANATION: CAPITALS INDICATE MATTER ADDED TO EXISTING LAW. [Brackets] indicate matter deleted from existing law. Underlining indicates amendments to bill. Strike out indicates matter stricken from the bill by amendment or deleted from the law by amendment. *sb0049* 2 SENATE BILL 49 1 WHEREAS, The poem -

Guide to the Best American Humorous Short Stories

МІНІСТЕРСТВО ОСВІТИ І НАУКИ УКРАЇНИ ДВНЗ “ПРИКАРПАТСЬКИЙ НАЦІОНАЛЬНИЙ УНІВЕРСИТЕТ ІМЕНІ ВАСИЛЯ СТЕФАНИКА” ФАКУЛЬТЕТ ІНОЗЕМНИХ МОВ КАФЕДРА АНГЛІЙСЬКОЇ ФІЛОЛОГІЇ САБАДАШ Д. В. Guide to the Best American Humorous Short Stories (G. P. Morris, E. A. Poe, C. M. S. Kirkland, E. Leslie, G. W. Curtis, E. E. Hale and O. W. Holmes) навчальний посібник для студентів 3 курсу Івано-Франківськ 2019 1 УДК 811.111 (075) ББК 81.2 Англ. C 12 Сабадаш Д.В. Guide to the Best American Humorous Short Stories (G. P. Morris, E. A. Poe, C. M. S. Kirkland, E. Leslie, G. W. Curtis, E. E. Hale and O. W. Holmes) : навчальний посібник для студентів 3 курсу. Бойчук А.Б. Івано-Франківськ, 2019. 60 с. Навчальний посібник створено з метою збагатити мовний запас студентів, сформувати у них навички читання, перекладу та усного мовлення, а також ознайомити їх із основами лінгвостилістичного аналізу художнього тексту. Посібник містить одинадцять розробок з комплексами вправ до семи автентичних англомовних оповідань американських авторів. У нього включено два додатки із проектними завданнями для самостійної роботи та глосарій літературних термінів. Розробки передбачають послідовне виконання практичних усних і письмових завдань, та спонукають студента до творчого підходу із залученням власних знань та досвіду. Навчальний посібник призначено для студентів англійського відділення, для студентів німецького та французького відділень, котрі вивчають англійську як другу мову, для аудиторної та самостійної роботи. РЕЦЕНЗЕНТИ: Венгринович Н. Р. – кандидат філологічних наук, доцент, доцент кафедри мовознавства Івано-Франківського національного медичного університету Романишин І. М. – кандидат педагогічних наук, доцент, доцент кафедри англійської філології Прикарпатського національного університету імені Василя Стефаника Друкується за ухвалою вченої ради факультету іноземних мов Прикарпатського національного університету імені Василя Стефаника (протокол № 3 від 25 червня 2019 р.) © Сабадаш Д.В. -

Tales from the Magazine Prison House: Democracy and Authorship in American Periodical Fiction, 1825-1850

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1994 Tales From the Magazine Prison House: Democracy and Authorship in American Periodical Fiction, 1825-1850. Laurence Scott eeplesP Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Peeples, Laurence Scott, "Tales From the Magazine Prison House: Democracy and Authorship in American Periodical Fiction, 1825-1850." (1994). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5750. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5750 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Poe As Magazinist

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 Poe as Magazinist Kay Ellen McKamy University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Scholar Commons Citation McKamy, Kay Ellen, "Poe as Magazinist" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3242 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Poe as Magazinist by Kay E. McKamy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-Major Professor: Rosalie Murphy Baum, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Regina Hewitt, Ph.D. Lawrence Broer, Ph.D. Elaine Smith, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 31, 2011 Keywords: short stories, American literature, George R. Graham, early American magazines, Graham‘s Magazine Copyright ©2011, Kay E. McKamy Acknowledgments The idea for this dissertation came from a discussion of early-American magazines in a graduate course with Dr. Rosalie Murphy Baum at the University of South Florida. The dissertation would not have been possible without the professionalism, knowledge, advice, and encouragement of Dr. Baum. Her combination of prodding and praise is exactly what non-traditional students like me need: without her insistence, I would have quit long ago. -

A Reader's History of American Literature

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Cornell University Library PS 92.H63 A reader's history of American ilteratur 3 1924 022 000 016 The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924022000016 md. READER'S HISTORY OF AMERICAN LITERATURE BY THOMAS WENTWORTH HIGGINSON AND HENRY WALCOTT BOYNTON m^^^^m BOSTON, NEW YORK AND CHICAGO HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY ^ht iSibetjiitic ^te^^, "ffamfiriBoe COPYRIGHT 1903 BY THOMAS WENTWORTH HIGGINSON AND HENRY W. BOYNTON ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PEEPACE This book is based upon a course of lec- tures delivered during January of 1903 be- fore the Lowell Institute in Boston. Their essential plan was that of concentrating atten- tion on leading figures, instead of burdening the memory with a great many minor names and data. Various hearers, including some teachers of literature, took pains to express their approval of this plan, and to suggest that the material might profitably be cast into book form. This necessarily meant a good deal of revision of a kind which the lecturer did not care to undertake ; and he was able to secure the cooperation of a younger asso- ciate, to whom has fallen the task of modify- ing and supplementing the original text, so far as either process was necessary in order to make a complete and consecutive, though still brief, narrative of the course of American iv PREFACE literature. The apparatus necessary for its use as a text-book has been supplied in an appendix, and is believed to be adequate. -

Chronology of the Life of Edgar Allan Poe 1. 1806

Chronology of the Life of Edgar Allan Poe 1. 1806 (March 14) - Traveling stage actors David Poe, Jr. and Elizabeth Arnold Hopkins marry. 2. 1807 (Jan. 30) - William Henry Leonard Poe (usually called Henry) is born to David and Elizabeth Poe in Boston. 3. 1809 (Jan. 19) - Edgar Poe is born in Boston. 4. 1810 (Dec. 20) - Rosalie Poe (often called Rosie or Rose) is born in Norfolk, Virginia. c. 1810: David Poe abandons the family 5. 1811 (Dec. 8) - Elizabeth Arnold Poe, Edgar’s mother, dies in Richmond, Virginia. Her remains are buried at Old St. John’s Church in old Richmond. (The circumstances surrounding David Poe’s death, and the reason why he was not with his family at the time, are shrouded in mystery.) 6. 1811 (Dec. 26) - The orphaned Edgar is taken into the home of John and Frances Allan of Richmond. His sister, Rosalie, is taken in by Mr. and Mrs. William Mackenzie, also of Richmond. His brother, Henry, remains in Baltimore with his grandparents. Allan never legally adopts Poe, although Poe calls John Allan “Pa” and Frances Allan “Ma.” John and Frances never have children of their own. John Allan has at least one illegitimate child (Edwin Collier). (After Frances’s death, John remarried in 1830 and had children through the second Mrs. Allan.) 7. 1812 (Jan. 7) - Poe is baptized by the Reverend John Buchanan and christened as “Edgar Allan Poe,” with the Allans presumably as godparents. Poe’s sister Rosalie is baptized on September 3, 1812 as “Rosalie Mackenzie Poe.” 8. 1814 - Five year old Edgar begins his formal education. -

The Story of a Southern State in the Union: Maryland in 1860 and 1861

The Story of a Southern State in the Union: Maryland in 1860 and 1861 Jack Sheehy HIS 242, “Origins of the American South” Dr. Michael Guasco Sheehy 2 Firing their rifles “wildly,” the soldiers fought back against the secessionist mob hurling stones at them as they marched down Pratt Street.1 Baltimore Mayor George William Brown thought it prudent to direct the commanding officer of the Sixth Massachusetts Regiment to slow his troops’ marching speed — double-quick time, the mayor felt, was too fast and would thus incite further panic. Brown had no military expertise, but that did not stop the determined mayor from taking charge. Nothing would. It was his city in chaos, after all. The soldiers slowed down as Brown began to march at the front of their unit, but the violence worsened.2 Rioters wrestled weapons away from the troops, continued throwing stones and bricks, and cheered in support of the newly-formed Confederate States of America.3 Four soldiers and twelve civilians died on the streets of Baltimore that day.4 Although this tumult on the morning of April 19th, 1861 terrified Marylanders, by this time they were already quite familiar with secessionism and the tense nature of the sectional crisis plaguing the nation. In Maryland, secessionists were present throughout 1860 and 1861 because of the state’s political climate, in which a disdain for outsider intervention, a fear of abolition, and a strong sense of Southernness prevailed. Maryland’s secession crisis experience has been regarded as an especially fascinating one, in part because on the surface it may appear to many that Maryland could have sided with either the Union or the seceding states.