Redalyc.Technology, Needs and Power As Means of Distribution and Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tommaso Campanella the Book and the Body of Nature Series: International Archives of the History of Ideas Archives Internationales D'histoire Des Idées

springer.com Germana Ernst Tommaso Campanella The Book and the Body of Nature Series: International Archives of the History of Ideas Archives internationales d'histoire des idées A comprehensive intellectual biography of an important and complex philosopher of the Renaissance A historical reconstruction of social and cultural relationships between the sixteenth and the seventeenth century A volume useful to clarify some philological and interpretative problems concerning modern editions and translations of Campanella’s texts A friend of Galileo and author of the renowned utopia The City of the Sun, Tommaso Campanella (Stilo, Calabria,1568- Paris, 1639) is one of the most significant and original thinkers of the early modern period. His philosophical project centred upon the idea of reconciling Renaissance philosophy with a radical reform of science and society. He produced a complex and articulate synthesis of all fields of knowledge – including magic and astrology. During his early formative years as a Dominican friar, he manifested a restless impatience 2010, XII, 281 p. towards Aristotelian philosophy and its followers. As a reaction, he enthusiastically embraced Bernardino Telesio’s view that knowledge could only be acquired through the observation of Printed book things themselves, investigated through the senses and based on a correct understanding of Hardcover the link between words and objects. Campanella’s new natural philosophy rested on the 139,99 € | £119.99 | $169.99 principle that the books written by men needed to be compared with God’s infinite book of [1]149,79 € (D) | 153,99 € (A) | CHF nature, allowing them to correct the mistakes scattered throughout the human ‘copies’ which 165,50 were always imperfect, partial and liable to revisions. -

Conversations with Stalin on Questions of Political Economy”

WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS Lee H. Hamilton, Conversations with Stalin on Christian Ostermann, Director Director Questions of Political Economy BOARD OF TRUSTEES: ADVISORY COMMITTEE: Joseph A. Cari, Jr., by Chairman William Taubman Steven Alan Bennett, Ethan Pollock (Amherst College) Vice Chairman Chairman Working Paper No. 33 PUBLIC MEMBERS Michael Beschloss The Secretary of State (Historian, Author) Colin Powell; The Librarian of Congress James H. Billington James H. Billington; (Librarian of Congress) The Archivist of the United States John W. Carlin; Warren I. Cohen The Chairman of the (University of Maryland- National Endowment Baltimore) for the Humanities Bruce Cole; The Secretary of the John Lewis Gaddis Smithsonian Institution (Yale University) Lawrence M. Small; The Secretary of Education James Hershberg Roderick R. Paige; (The George Washington The Secretary of Health University) & Human Services Tommy G. Thompson; Washington, D.C. Samuel F. Wells, Jr. PRIVATE MEMBERS (Woodrow Wilson Center) Carol Cartwright, July 2001 John H. Foster, Jean L. Hennessey, Sharon Wolchik Daniel L. Lamaute, (The George Washington Doris O. Mausui, University) Thomas R. Reedy, Nancy M. Zirkin COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES CHRISTIAN F. OSTERMANN, Series Editor This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. -

Boundaries of Utopia – Imagining Communism from Plato to Stalin

Boundaries of Utopia – Imagining Communism from Plato to Stalin The idea that socialism could be established in a single country was adopted as an official doctrine by the Soviet Union in 1925, Stalin and Bukharin being the main formulators of the policy. Before this there had been much debate as to whether the only way to secure socialism would be as a result of socialist revolution on a much broader scale, across all Europe or wider still. This book traces the development of ideas about communist utopia from Plato onwards, paying particular attention to debates about universalist ideology versus the possibility for ‘socialism in one country’. The book argues that although the prevailing view is that ‘socialism in one country’ was a sharp break from a long tradition that tended to view socialism as only possible if universal, in fact the territorially confined socialist project had long roots, including in the writings of Marx and Engels. Erik van Ree is an Assistant Professor at the Institute of European Studies at the University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Routledge Contemporary Russia and Eastern Europe Series 1 Liberal Nationalism in 7 The Telengits of Central Europe Southern Siberia Stefan Auer Landscape, religion and knowledge in motion 2 Civil-Military Relations in Agnieszka Halemba Russia and Eastern Europe David J. Betz 8 The Development of Capitalism in Russia 3 The Extreme Nationalist Simon Clarke Threat in Russia The growing influence of 9 Russian Television Today Western Rightist ideas Primetime drama and comedy Thomas Parland -

Sos Political Science & Public Administration M.A.Political Science

Sos Political science & Public administration M.A.Political Science II Sem Political Philosophy:Mordan Political Thought, Theory & contemporary Ideologies(201) UNIT-IV Topic Name-Utopian Socialism What is utopian society? • A utopia is an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its citizens.The opposite of a utopia is a dystopia. • Utopia focuses on equality in economics, government and justice, though by no means exclusively, with the method and structure of proposed implementation varying based on ideology.According to Lyman Tower SargentSargent argues that utopia's nature is inherently contradictory, because societies are not homogenous and have desires which conflict and therefore cannot simultaneously be satisfied. • The term utopia was created from Greek by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book Utopia, describing a fictional island society in the south Atlantic Ocean off the coast of South America Who started utopian socialism? • Charles Fourier was a French socialist who lived from 1772 until 1837 and is credited with being an early Utopian Socialist similar to Robert Owen. He wrote several works related to his socialist ideas which centered on his main idea for society: small communities based on cooperation Definition of utopian socialism • socialism based on a belief that social ownership of the means of production can be achieved by voluntary and peaceful surrender of their holdings by propertied groups What is the goal of utopian societies? • The aim of a utopian society is to promote the highest quality of living possible. The word 'utopia' was coined by the English philosopher, Sir Thomas More, in his 1516 book, Utopia, which is about a fictional island community. -

Philosophy of Mind

Introduction to Philosophy: Philosophy of Mind INTRODUCTION TO PHILOSOPHY: PHILOSOPHY OF MIND ERAN ASOULIN, PAUL RICHARD BLUM, TONY CHENG, DANIEL HAAS, JASON NEWMAN, HENRY SHEVLIN, ELLY VINTIADIS, HEATHER SALAZAR (EDITOR), AND CHRISTINA HENDRICKS (SERIES EDITOR) Rebus Community Introduction to Philosophy: Philosophy of Mind by Eran Asoulin, Paul Richard Blum, Tony Cheng, Daniel Haas, Jason Newman, Henry Shevlin, Elly Vintiadis, Heather Salazar (Editor), and Christina Hendricks (Series Editor) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. CONTENTS What is an open textbook? vii Christina Hendricks How to access and use the books ix Christina Hendricks Introduction to the Series xi Christina Hendricks Praise for the Book xiv Adriano Palma Acknowledgements xv Heather Salazar and Christina Hendricks Introduction to the Book 1 Heather Salazar 1. Substance Dualism in Descartes 3 Paul Richard Blum 2. Materialism and Behaviorism 10 Heather Salazar 3. Functionalism 19 Jason Newman 4. Property Dualism 26 Elly Vintiadis 5. Qualia and Raw Feels 34 Henry Shevlin 6. Consciousness 41 Tony Cheng 7. Concepts and Content 49 Eran Asoulin 8. Freedom of the Will 58 Daniel Haas About the Contributors 69 Feedback and Suggestions 72 Adoption Form 73 Licensing and Attribution Information 74 Review Statement 76 Accessibility Assessment 77 Version History 79 WHAT IS AN OPEN TEXTBOOK? CHRISTINA HENDRICKS An open textbook is like a commercial textbook, except: (1) it is publicly available online free of charge (and at low-cost in print), and (2) it has an open license that allows others to reuse it, download and revise it, and redistribute it. -

Michael Schumann Hoffnung PDS Reden, Aufsätze, Entwürfe 1989–2000 Rls 12 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Texte 12 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung

Wolfram Adolphi (Hrsg.) Michael Schumann Hoffnung PDS Reden, Aufsätze, Entwürfe 1989–2000 rls 12 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Texte 12 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung WOLFRAM ADOLPHI (HRSG.) Michael Schumann Hoffnung PDS Reden, Aufsätze, Entwürfe 1989-2000 Mit einem Geleitwort von Lothar Bisky Karl Dietz Verlag Berlin Herausgegeben mit Unterstützung der PDS-Fraktion im Landtag Brandenburg. Ein besonderer Dank gilt Herrn Marco Schumann, Potsdam, für seine Hilfe und Mitarbeit. Wolfram Adolphi (Hrsg.): Michael Schumann. Hoffnung PDS Reden, Aufsätze, Entwürfe 1989-2000. Mit einem Geleitwort von Lothar Bisky (Reihe: Texte/Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung; Bd. 12) Berlin: Dietz, 2004 ISBN 3-320-02948-7 © Karl Dietz Verlag Berlin GmbH 2004 Satz: Jörn Schütrumpf Umschlag, Druck und Verarbeitung: MediaService GmbH BärenDruck und Werbung Printed in Germany Inhalt LOTHAR BISKY Zum Geleit 9 WOLFRAM ADOLPHI Vorwort 11 Abschnitt 1 Zum Herkommen und zur Entwicklung der PDS Wir brechen unwiderruflich mit dem Stalinismus als System! Referat auf dem Außerordentlichen Parteitag der SED in Berlin am 16. Dezember 1989 33 Von der SED zur PDS – geht die Rechnung auf? Interview für die Tageszeitung »Neues Deutschland« vom 26. Januar 1990 57 Programmatik und politisches System Artikel für die vom PDS-Parteivorstand herausgegebene Zeitschrift »Disput«, Heft 14/1992 (2. Juliheft) 69 Souverän mit unserer politischen Biographie umgehen Referat auf dem 3. Parteitag der PDS in Berlin (19.-21. Januar 1993) 74 Der Logik des Kräfteverhältnisses stellen! Rede auf dem 12. Parteitag der DKP, Gladbeck, am 13. November 1993 90 5 Vor fünf Jahren: »Wir brechen unwiderruflich mit dem Stalinismus als System!« Reminiszenzen und aktuelle Überlegungen 94 Antikommunismus? Schlußwort auf dem Historisch-rechtspolitischen Kolloquium »KPD-Verbot oder mit Kommunisten leben? Das KPD-Verbotsurteil des Bundesverfassungsgerichts vom 17. -

Renaissance Quarterly Books Received: January–March 2011

Renaissance Quarterly Books Received: January–March 2011 EDITIONS AND TRANSLATIONS: Alexander, Gavin R. Writing after Sidney: The Literary Response to Sir Philip Sidney 1586– 1640. Paperback edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. xliv + 380 pp. index. illus. bibl. $55. ISBN: 978–0–19–959112–1. Barbour, Richmond. The Third Voyage Journals: Writing and Performance in the London East India Company, 1607–10. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. 281 pp. index. append. illus. gloss. bibl. $75. ISBN: 978–0–230–61675–2. Buchanan, George. Poetic Paraphrase of The Psalms of David. Ed. Roger P. H. Green. Geneva: Librairie Droz S.A., 2011. 640 pp. index. append. bibl. $115. ISBN: 978–2–600–01445–8. Campbell, Gordon, and Thomas N. Corns, eds. John Milton: Life, Work, and Thought. Paperback edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. xv + 488 pp. index. illus. map. bibl. $24.95. ISBN: 978–0–19–959103–9. Calderini, Domizio. Commentary on Silius Italicus. Travaux d’Humanisme et Renaissance 477. Ed. Frances Muecke and John Dunston. Geneva: Librairie Droz S.A., 2010. 958 pp. index. tbls. bibl. $150. ISBN: 978–2–600–01434–2 (cl), 978–2–600–01434–2 (pbk). Campanella, Tommaso. Selected Philosophical Poems of Tommaso Campanella: A Bilingual Edition. Ed. Sherry L. Roush. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2011. xi + 248 pp. index. bibl. $45. ISBN: 978–0–226–09205–8. Castner, Catherine J., trans. Biondo Flavio’s Italia Illustrata: Text, Translation, and Commentary. Volume 2: Central and Southern Italy. Binghamton: Global Academic Publishing, 2009. xvi + 488 pp. index. illus. map. bibl. $36. ISBN: 978–1–58684–278–9. -

Maurice Finocchiaro Discusses the Lessons and the Cultural Repercussions of Galileo’S Telescopic Discoveries.” Physics World, Vol

MAURICE A. FINOCCHIARO: CURRICULUM VITAE CONTENTS: §0. Summary and Highlights; §1. Miscellaneous Details; §2. Teaching Experience; §3. Major Awards and Honors; §4. Publications: Books; §5. Publications: Articles, Chapters, and Discussions; §6. Publications: Book Reviews; §7. Publications: Proceedings, Abstracts, Translations, Reprints, Popular Media, etc.; §8. Major Lectures at Scholarly Meetings: Keynote, Invited, Funded, Honorarium, etc.; §9. Other Lectures at Scholarly Meetings; §10. Public Lectures; §11. Research Activities: Out-of-Town Libraries, Archives, and Universities; §12. Professional Service: Journal Editorial Boards; §13. Professional Service: Refereeing; §14. Professional Service: Miscellaneous; §15. Community Service §0. SUMMARY AND HIGHLIGHTS Address: Department of Philosophy; University of Nevada, Las Vegas; Box 455028; Las Vegas, NV 89154-5028. Education: B.S., 1964, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Ph.D., 1969, University of California, Berkeley. Position: Distinguished Professor of Philosophy, Emeritus; University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Previous Positions: UNLV: Assistant Professor, 1970-74; Associate Professor, 1974-77; Full Professor, 1977-91; Distinguished Professor, 1991-2003; Department Chair, 1989-2000. Major Awards and Honors: 1976-77 National Science Foundation; one-year grant; project “Galileo and the Art of Reasoning.” 1983-84 National Endowment for the Humanities, one-year Fellowship for College Teachers; project “Gramsci and the History of Dialectical Thought.” 1987 Delivered the Fourth Evert Willem Beth Lecture, sponsored by the Evert Willem Beth Foundation, a committee of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Sciences, at the Universities of Amsterdam and of Groningen. 1991-92 American Council of Learned Societies; one-year fellowship; project “Democratic Elitism in Mosca and Gramsci.” 1992-95 NEH; 3-year grant; project “Galileo on the World Systems.” 1993 State of Nevada, Board of Regents’ Researcher Award. -

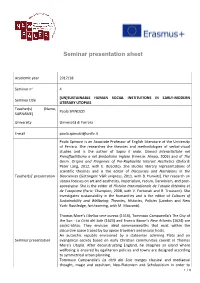

Seminar Presentation Sheet

Seminar presentation sheet Academic year 2017/18 Seminar n° 4 [UN]SUSTAINABLE HUMAN SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS IN EARLY-MODERN Seminar title LITERARY UTOPIAS Teacher(s) (Name, Paola SPINOZZI SURNAME) University Università di Ferrara E-mail [email protected] Paola Spinozzi is an Associate Professor of English Literature at the University of Ferrara. She researches the theories and methodologies of verbal-visual studies and is the author of Sopra il reale. Osmosi interartistiche nel Preraffaellitismo e nel Simbolismo inglese (Firenze: Alinea, 2005) and of The Germ. Origins and Progenies of Pre-Raphaelite Interart Aesthetics (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2012, with E. Bizzotto). She studies literary representations of scientific theories and is the editor of Discourses and Narrations in the Teacher(s)’ presentation Biosciences (Göttingen: V&R unipress, 2011, with B. Hurwitz). Her research on utopia focuses on art and aesthetics, imperialism, racism, Darwinism, and post- apocalypse. She is the editor of Histoire transnationale de l’utopie littéraire et de l’utopisme (Paris: Champion, 2008, with V. Fortunati and R. Trousson). She investigates sustainability in the humanities and is the editor of Cultures of Sustainability and Wellbeing: Theories, Histories, Policies (London and New York: Routledge, forthcoming, with M. Mazzanti). Thomas More’s Libellus vere aureus (1516), Tommaso Campanella’s The City of the Sun - La Città del Sole (1623) and Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis (1624) are ού/εύ-τόποι. They envision ideal commonwealths that exist within the discursive space traced by European travellers and insular hosts. An autarchic republic envisioned by a statesman admiring Plato and an Seminar presentation evangelical society based on early Christian communities coexist in Thomas More’s Utopia. -

Karl Marx Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844

Karl Marx Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 Karl Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. Progress Publishers, Moscow 1959; Translated by Martin Milligan, revised by Dirk J. Struik, contained in Marx/Engels, Gesamtausgabe, Abt. 1, Bd. 3. First Manuscript Wages of Labor Wages are determined through the antagonistic struggle between capitalist and worker. Victory goes necessarily to the capitalist. The capitalist can live longer without the worker than can the worker without the capitalist. Combination among the capitalists is customary and effective; workers’ combination is prohibited and painful in its consequences for them. Besides, the landowner and the capitalist can make use of industrial advantages to augment their revenues; the worker has neither rent nor interest on capital to supplement his industrial income. Hence the intensity of the competition among the workers. Thus only for the workers is the separation of capital, landed property, and labour an inevitable, essential and detrimental separation. Capital and landed property need not remain fixed in this abstraction, as must the labor of the workers. The separation of capital, rent, and labor is thus fatal for the worker. The lowest and the only necessary wage rate is that providing for the subsistence of the worker for the duration of his work and as much more as is necessary for him to support a family and for the race of laborers not to die out. The ordinary wage, according to Smith, is the lowest compatible with common humanity6, that is, with cattle-like existence. The demand for men necessarily governs the production of men, as of every other commodity. -

Journeying Through Utopia: Anarchism, Geographical Imagination and Performative Futures in Marie-Louise Berneri’S Works

Investigaciones Geográficas • Instituto de Geografía •UNAM eISSN: 2448-7279 • DOI: dx.doi.org/10.14350/rig.60026 • ARTÍCULOS Núm. 100 • Diciembre • 2019 • e60026 www.investigacionesgeograficas.unam.mx Journeying through Utopia: anarchism, geographical imagination and performative futures in Marie-Louise Berneri’s works Un viaje a través de la utopía: anarquismo, imaginación geográfica y futuros performativos en la obra de Marie-Louise Berneri Federico Ferretti* Recibido: 25/07/2019. Aceptado: 12/09/2019. Publicado: 1/12/2019. Abstract. This paper addresses works and archives of Resumen. Este articulo aborda los trabajos y archivos de transnational anarchist intellectual Marie-Louise Berneri la militante anarquista transnacional Maria Luisa Berneri (1918-1949), author of a neglected but very insightful (1918-1949), autora de un estudio poco conocido pero muy history of utopias and of their spaces. Extending current significativo sobre las historias de las utopías y sus espacios. literature on anarchist geographies, utopianism and on the Al ampliar la literatura actual sobre geografías anarquistas, relation between geography and the humanities, I argue utopismo y sobre la relación entre la geografía y las ‘humani- that a distinction between authoritarian and libertarian dades’, defiendo que una distinción entre utopías libertarias utopias is key to understanding the political relevance of y utopías autoritarias es esencial para comprender la impor- the notion of utopia, which is also a matter of space and tancia política del concepto de utopía, que es también un geographical imagination. Berneri’s criticisms to utopia were asunto de espacio y de imaginación geográfica. Las críticas eventually informed by notions of anti-colonialism and anti- de Berneri a la utopía se inspiraron en su anticolonialismo y authoritarianism, especially referred to her original critique su antiautoritarismo, centrado especialmente en su original of twentieth-century totalitarian regimes. -

Université De Montréal Balkan Als Poetischer Raum. Peter Handkes Werk Im Spiegel Der Morawischen Nacht Par Snježana Rafo

Université de Montréal Balkan als poetischer Raum. Peter Handkes Werk im Spiegel der Morawischen Nacht par Snježana Rafo Département de littératures et de langues modernes Faculté des arts et des sciences Thèse présentée à la Faculté des études supérieures en vue de l'obtention du grade de PH.D. en études allemandes option littérature Août 2013 © Snježana Rafo, 2013 Université de Montréal Faculté des études supérieures Cette thèse intitulée: Balkan als poetischer Raum. Peter Handkes Werk im Spiegel der Morawischen Nacht présentée par: Snježana Rafo a été évaluée par un jury composé des personnes suivantes : Nikola von Merveldt, présidente-rapporteuse Jürgen Heizmann, directeur de recherche Till van Rahden, membre du jury Bernhard Fetz, examinateur externe Barbara Agnese, représentante du doyen de la Faculté I. Résumé Die morawische Nacht (2008) de Peter Handke représente un tournant: l’auteur y renonce à son engagement politique concernant les Balkans et il revient au « royaume de la poésie ». En reprenant des concepts de la théorie de l’espace dans les études culturelles, cette étude examine les moyens narratifs à partir desquels Handke projette une nouvelle image des Balkans. L’écrivain autrichien déconstruit son propre mythe du « Neuvième Pays » (Die Wiederholung, 1986), dont il a sans cesse défendu le concept dans les années 1990 (Eine winterliche Reise, 1996; Zurüstungen für die Unsterblichkeit, 1997; Die Fahrt im Einbaum, 1999; Unter Tränen fragend, 1999). Dans Die morawische Nacht, de fréquentes allusions et connotations nous ramènent aux œuvres antérieures, mentionnées ci-dessus. La signification et la fonction des nouvelles images des Balkans ne sont pas comprises que dans le cadre des références intertextuelles.