03-01-2020 Stakeholder Management, Cooperatives, and Selfish-Individualism 1131

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tommaso Campanella the Book and the Body of Nature Series: International Archives of the History of Ideas Archives Internationales D'histoire Des Idées

springer.com Germana Ernst Tommaso Campanella The Book and the Body of Nature Series: International Archives of the History of Ideas Archives internationales d'histoire des idées A comprehensive intellectual biography of an important and complex philosopher of the Renaissance A historical reconstruction of social and cultural relationships between the sixteenth and the seventeenth century A volume useful to clarify some philological and interpretative problems concerning modern editions and translations of Campanella’s texts A friend of Galileo and author of the renowned utopia The City of the Sun, Tommaso Campanella (Stilo, Calabria,1568- Paris, 1639) is one of the most significant and original thinkers of the early modern period. His philosophical project centred upon the idea of reconciling Renaissance philosophy with a radical reform of science and society. He produced a complex and articulate synthesis of all fields of knowledge – including magic and astrology. During his early formative years as a Dominican friar, he manifested a restless impatience 2010, XII, 281 p. towards Aristotelian philosophy and its followers. As a reaction, he enthusiastically embraced Bernardino Telesio’s view that knowledge could only be acquired through the observation of Printed book things themselves, investigated through the senses and based on a correct understanding of Hardcover the link between words and objects. Campanella’s new natural philosophy rested on the 139,99 € | £119.99 | $169.99 principle that the books written by men needed to be compared with God’s infinite book of [1]149,79 € (D) | 153,99 € (A) | CHF nature, allowing them to correct the mistakes scattered throughout the human ‘copies’ which 165,50 were always imperfect, partial and liable to revisions. -

The Atheist's Bible: Diderot's 'Éléments De Physiologie'

The Atheist’s Bible Diderot’s Éléments de physiologie Caroline Warman In off ering the fi rst book-length study of the ‘Éléments de physiologie’, Warman raises the stakes high: she wants to show that, far from being a long-unknown draf , it is a powerful philosophical work whose hidden presence was visible in certain circles from the Revolut on on. And it works! Warman’s study is original and st mulat ng, a historical invest gat on that is both rigorous and fascinat ng. —François Pépin, École normale supérieure, Lyon This is high-quality intellectual and literary history, the erudit on and close argument suff used by a wit and humour Diderot himself would surely have appreciated. —Michael Moriarty, University of Cambridge In ‘The Atheist’s Bible’, Caroline Warman applies def , tenacious and of en wit y textual detect ve work to the case, as she explores the shadowy passage and infl uence of Diderot’s materialist writ ngs in manuscript samizdat-like form from the Revolut onary era through to the Restorat on. —Colin Jones, Queen Mary University of London ‘Love is harder to explain than hunger, for a piece of fruit does not feel the desire to be eaten’: Denis Diderot’s Éléments de physiologie presents a world in fl ux, turning on the rela� onship between man, ma� er and mind. In this late work, Diderot delves playfully into the rela� onship between bodily sensa� on, emo� on and percep� on, and asks his readers what it means to be human in the absence of a soul. -

Conversations with Stalin on Questions of Political Economy”

WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS Lee H. Hamilton, Conversations with Stalin on Christian Ostermann, Director Director Questions of Political Economy BOARD OF TRUSTEES: ADVISORY COMMITTEE: Joseph A. Cari, Jr., by Chairman William Taubman Steven Alan Bennett, Ethan Pollock (Amherst College) Vice Chairman Chairman Working Paper No. 33 PUBLIC MEMBERS Michael Beschloss The Secretary of State (Historian, Author) Colin Powell; The Librarian of Congress James H. Billington James H. Billington; (Librarian of Congress) The Archivist of the United States John W. Carlin; Warren I. Cohen The Chairman of the (University of Maryland- National Endowment Baltimore) for the Humanities Bruce Cole; The Secretary of the John Lewis Gaddis Smithsonian Institution (Yale University) Lawrence M. Small; The Secretary of Education James Hershberg Roderick R. Paige; (The George Washington The Secretary of Health University) & Human Services Tommy G. Thompson; Washington, D.C. Samuel F. Wells, Jr. PRIVATE MEMBERS (Woodrow Wilson Center) Carol Cartwright, July 2001 John H. Foster, Jean L. Hennessey, Sharon Wolchik Daniel L. Lamaute, (The George Washington Doris O. Mausui, University) Thomas R. Reedy, Nancy M. Zirkin COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES CHRISTIAN F. OSTERMANN, Series Editor This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. -

The OT Is the World's Supreme Document on the Subject of Justice. God Purposes, After and Through the Cosmic-Historic Mess [&Quo

LIBERTY AND/OR EQUALITY in relation to the four isms Elliott #856 The OT is the world's supreme document on the subject of justice. God purposes, after and through the cosmic-historic mess ["the the victory of "righteous- ness and justice" [Gen.18.19] through a nation [Gen.12.2] different from the other nations [Num.23.9]--a nation founded on faith [Abraham in Gen.] and obedience [Moses in Ex.--the two sagas converged in the Joseph-reconciliation saga]. When the nation self-idolatrizes into nationalism, God's purpose of "righteousness [in character] and justice [in structure and processl"is frustrant. When faith/liberty vaunt them- selves over obedience/equality, justice is destroyed [a tendency of Declaration of Independence thinking]. When the reverse occurs, again justice is destroyed [as in the Communist Manifesto, which reverts romantically to the pre-nation communitar- ian ideal--a despotic regime setting itself up, in anticipation of the withering away of the state, on behalf of the proles as "the dictatorship of the proletariatl. 1. Neither of the two nation motifs now dominating the globe bodies forth the bib- lical ideal of "liberty with justice [in equality] for all." "Democracy" [the liber- ty motif] and "communism" [the equality motif] are alike in dedication to justice. NB: As ideal terms, I follow here my old teacher Mortimer Adler: "democracy" as the ideal term for political justice, "socialism" as the ideal term for economic justice --and "communism" useless as an ideal term, for it combines "socialism" and tyranny, buying pseudo-equaity at the price of liberty [i.e., political justice, "freedom," the rights of the individual as spelled out in the UN's "Universal Declaration of Human Rights" 7rwhich is thinksheet #831]. -

9780748678662.Pdf

PREHISTORIC MYTHS IN MODERN POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY 55200_Widerquist.indd200_Widerquist.indd i 225/11/165/11/16 110:320:32 AAMM 55200_Widerquist.indd200_Widerquist.indd iiii 225/11/165/11/16 110:320:32 AAMM PREHISTORIC MYTHS IN MODERN POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY Karl Widerquist and Grant S. McCall 55200_Widerquist.indd200_Widerquist.indd iiiiii 225/11/165/11/16 110:320:32 AAMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Karl Widerquist and Grant S. McCall, 2017 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road, 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry, Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/13 Adobe Sabon by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 7866 2 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 7867 9 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 0 7486 7869 3 (epub) The right of Karl Widerquist and Grant S. McCall to be identifi ed as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 55200_Widerquist.indd200_Widerquist.indd iivv 225/11/165/11/16 110:320:32 AAMM CONTENTS Preface vii Acknowledgments -

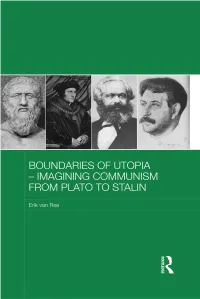

Boundaries of Utopia – Imagining Communism from Plato to Stalin

Boundaries of Utopia – Imagining Communism from Plato to Stalin The idea that socialism could be established in a single country was adopted as an official doctrine by the Soviet Union in 1925, Stalin and Bukharin being the main formulators of the policy. Before this there had been much debate as to whether the only way to secure socialism would be as a result of socialist revolution on a much broader scale, across all Europe or wider still. This book traces the development of ideas about communist utopia from Plato onwards, paying particular attention to debates about universalist ideology versus the possibility for ‘socialism in one country’. The book argues that although the prevailing view is that ‘socialism in one country’ was a sharp break from a long tradition that tended to view socialism as only possible if universal, in fact the territorially confined socialist project had long roots, including in the writings of Marx and Engels. Erik van Ree is an Assistant Professor at the Institute of European Studies at the University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Routledge Contemporary Russia and Eastern Europe Series 1 Liberal Nationalism in 7 The Telengits of Central Europe Southern Siberia Stefan Auer Landscape, religion and knowledge in motion 2 Civil-Military Relations in Agnieszka Halemba Russia and Eastern Europe David J. Betz 8 The Development of Capitalism in Russia 3 The Extreme Nationalist Simon Clarke Threat in Russia The growing influence of 9 Russian Television Today Western Rightist ideas Primetime drama and comedy Thomas Parland -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Sos Political Science & Public Administration M.A.Political Science

Sos Political science & Public administration M.A.Political Science II Sem Political Philosophy:Mordan Political Thought, Theory & contemporary Ideologies(201) UNIT-IV Topic Name-Utopian Socialism What is utopian society? • A utopia is an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its citizens.The opposite of a utopia is a dystopia. • Utopia focuses on equality in economics, government and justice, though by no means exclusively, with the method and structure of proposed implementation varying based on ideology.According to Lyman Tower SargentSargent argues that utopia's nature is inherently contradictory, because societies are not homogenous and have desires which conflict and therefore cannot simultaneously be satisfied. • The term utopia was created from Greek by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book Utopia, describing a fictional island society in the south Atlantic Ocean off the coast of South America Who started utopian socialism? • Charles Fourier was a French socialist who lived from 1772 until 1837 and is credited with being an early Utopian Socialist similar to Robert Owen. He wrote several works related to his socialist ideas which centered on his main idea for society: small communities based on cooperation Definition of utopian socialism • socialism based on a belief that social ownership of the means of production can be achieved by voluntary and peaceful surrender of their holdings by propertied groups What is the goal of utopian societies? • The aim of a utopian society is to promote the highest quality of living possible. The word 'utopia' was coined by the English philosopher, Sir Thomas More, in his 1516 book, Utopia, which is about a fictional island community. -

Philosophy of Mind

Introduction to Philosophy: Philosophy of Mind INTRODUCTION TO PHILOSOPHY: PHILOSOPHY OF MIND ERAN ASOULIN, PAUL RICHARD BLUM, TONY CHENG, DANIEL HAAS, JASON NEWMAN, HENRY SHEVLIN, ELLY VINTIADIS, HEATHER SALAZAR (EDITOR), AND CHRISTINA HENDRICKS (SERIES EDITOR) Rebus Community Introduction to Philosophy: Philosophy of Mind by Eran Asoulin, Paul Richard Blum, Tony Cheng, Daniel Haas, Jason Newman, Henry Shevlin, Elly Vintiadis, Heather Salazar (Editor), and Christina Hendricks (Series Editor) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. CONTENTS What is an open textbook? vii Christina Hendricks How to access and use the books ix Christina Hendricks Introduction to the Series xi Christina Hendricks Praise for the Book xiv Adriano Palma Acknowledgements xv Heather Salazar and Christina Hendricks Introduction to the Book 1 Heather Salazar 1. Substance Dualism in Descartes 3 Paul Richard Blum 2. Materialism and Behaviorism 10 Heather Salazar 3. Functionalism 19 Jason Newman 4. Property Dualism 26 Elly Vintiadis 5. Qualia and Raw Feels 34 Henry Shevlin 6. Consciousness 41 Tony Cheng 7. Concepts and Content 49 Eran Asoulin 8. Freedom of the Will 58 Daniel Haas About the Contributors 69 Feedback and Suggestions 72 Adoption Form 73 Licensing and Attribution Information 74 Review Statement 76 Accessibility Assessment 77 Version History 79 WHAT IS AN OPEN TEXTBOOK? CHRISTINA HENDRICKS An open textbook is like a commercial textbook, except: (1) it is publicly available online free of charge (and at low-cost in print), and (2) it has an open license that allows others to reuse it, download and revise it, and redistribute it. -

Michael Schumann Hoffnung PDS Reden, Aufsätze, Entwürfe 1989–2000 Rls 12 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Texte 12 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung

Wolfram Adolphi (Hrsg.) Michael Schumann Hoffnung PDS Reden, Aufsätze, Entwürfe 1989–2000 rls 12 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Texte 12 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung WOLFRAM ADOLPHI (HRSG.) Michael Schumann Hoffnung PDS Reden, Aufsätze, Entwürfe 1989-2000 Mit einem Geleitwort von Lothar Bisky Karl Dietz Verlag Berlin Herausgegeben mit Unterstützung der PDS-Fraktion im Landtag Brandenburg. Ein besonderer Dank gilt Herrn Marco Schumann, Potsdam, für seine Hilfe und Mitarbeit. Wolfram Adolphi (Hrsg.): Michael Schumann. Hoffnung PDS Reden, Aufsätze, Entwürfe 1989-2000. Mit einem Geleitwort von Lothar Bisky (Reihe: Texte/Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung; Bd. 12) Berlin: Dietz, 2004 ISBN 3-320-02948-7 © Karl Dietz Verlag Berlin GmbH 2004 Satz: Jörn Schütrumpf Umschlag, Druck und Verarbeitung: MediaService GmbH BärenDruck und Werbung Printed in Germany Inhalt LOTHAR BISKY Zum Geleit 9 WOLFRAM ADOLPHI Vorwort 11 Abschnitt 1 Zum Herkommen und zur Entwicklung der PDS Wir brechen unwiderruflich mit dem Stalinismus als System! Referat auf dem Außerordentlichen Parteitag der SED in Berlin am 16. Dezember 1989 33 Von der SED zur PDS – geht die Rechnung auf? Interview für die Tageszeitung »Neues Deutschland« vom 26. Januar 1990 57 Programmatik und politisches System Artikel für die vom PDS-Parteivorstand herausgegebene Zeitschrift »Disput«, Heft 14/1992 (2. Juliheft) 69 Souverän mit unserer politischen Biographie umgehen Referat auf dem 3. Parteitag der PDS in Berlin (19.-21. Januar 1993) 74 Der Logik des Kräfteverhältnisses stellen! Rede auf dem 12. Parteitag der DKP, Gladbeck, am 13. November 1993 90 5 Vor fünf Jahren: »Wir brechen unwiderruflich mit dem Stalinismus als System!« Reminiszenzen und aktuelle Überlegungen 94 Antikommunismus? Schlußwort auf dem Historisch-rechtspolitischen Kolloquium »KPD-Verbot oder mit Kommunisten leben? Das KPD-Verbotsurteil des Bundesverfassungsgerichts vom 17. -

Renaissance Quarterly Books Received: January–March 2011

Renaissance Quarterly Books Received: January–March 2011 EDITIONS AND TRANSLATIONS: Alexander, Gavin R. Writing after Sidney: The Literary Response to Sir Philip Sidney 1586– 1640. Paperback edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. xliv + 380 pp. index. illus. bibl. $55. ISBN: 978–0–19–959112–1. Barbour, Richmond. The Third Voyage Journals: Writing and Performance in the London East India Company, 1607–10. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. 281 pp. index. append. illus. gloss. bibl. $75. ISBN: 978–0–230–61675–2. Buchanan, George. Poetic Paraphrase of The Psalms of David. Ed. Roger P. H. Green. Geneva: Librairie Droz S.A., 2011. 640 pp. index. append. bibl. $115. ISBN: 978–2–600–01445–8. Campbell, Gordon, and Thomas N. Corns, eds. John Milton: Life, Work, and Thought. Paperback edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. xv + 488 pp. index. illus. map. bibl. $24.95. ISBN: 978–0–19–959103–9. Calderini, Domizio. Commentary on Silius Italicus. Travaux d’Humanisme et Renaissance 477. Ed. Frances Muecke and John Dunston. Geneva: Librairie Droz S.A., 2010. 958 pp. index. tbls. bibl. $150. ISBN: 978–2–600–01434–2 (cl), 978–2–600–01434–2 (pbk). Campanella, Tommaso. Selected Philosophical Poems of Tommaso Campanella: A Bilingual Edition. Ed. Sherry L. Roush. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2011. xi + 248 pp. index. bibl. $45. ISBN: 978–0–226–09205–8. Castner, Catherine J., trans. Biondo Flavio’s Italia Illustrata: Text, Translation, and Commentary. Volume 2: Central and Southern Italy. Binghamton: Global Academic Publishing, 2009. xvi + 488 pp. index. illus. map. bibl. $36. ISBN: 978–1–58684–278–9. -

Maurice Finocchiaro Discusses the Lessons and the Cultural Repercussions of Galileo’S Telescopic Discoveries.” Physics World, Vol

MAURICE A. FINOCCHIARO: CURRICULUM VITAE CONTENTS: §0. Summary and Highlights; §1. Miscellaneous Details; §2. Teaching Experience; §3. Major Awards and Honors; §4. Publications: Books; §5. Publications: Articles, Chapters, and Discussions; §6. Publications: Book Reviews; §7. Publications: Proceedings, Abstracts, Translations, Reprints, Popular Media, etc.; §8. Major Lectures at Scholarly Meetings: Keynote, Invited, Funded, Honorarium, etc.; §9. Other Lectures at Scholarly Meetings; §10. Public Lectures; §11. Research Activities: Out-of-Town Libraries, Archives, and Universities; §12. Professional Service: Journal Editorial Boards; §13. Professional Service: Refereeing; §14. Professional Service: Miscellaneous; §15. Community Service §0. SUMMARY AND HIGHLIGHTS Address: Department of Philosophy; University of Nevada, Las Vegas; Box 455028; Las Vegas, NV 89154-5028. Education: B.S., 1964, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Ph.D., 1969, University of California, Berkeley. Position: Distinguished Professor of Philosophy, Emeritus; University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Previous Positions: UNLV: Assistant Professor, 1970-74; Associate Professor, 1974-77; Full Professor, 1977-91; Distinguished Professor, 1991-2003; Department Chair, 1989-2000. Major Awards and Honors: 1976-77 National Science Foundation; one-year grant; project “Galileo and the Art of Reasoning.” 1983-84 National Endowment for the Humanities, one-year Fellowship for College Teachers; project “Gramsci and the History of Dialectical Thought.” 1987 Delivered the Fourth Evert Willem Beth Lecture, sponsored by the Evert Willem Beth Foundation, a committee of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Sciences, at the Universities of Amsterdam and of Groningen. 1991-92 American Council of Learned Societies; one-year fellowship; project “Democratic Elitism in Mosca and Gramsci.” 1992-95 NEH; 3-year grant; project “Galileo on the World Systems.” 1993 State of Nevada, Board of Regents’ Researcher Award.