Existentialism & Libertarianism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pride and Sexual Friendship: the Battle of the Sexes in Nietzsche's Post-Democratic World

PRIDE AND SEXUAL FRIENDSHIP: THE BATTLE OF THE SEXES IN NIETZSCHE’S POST-DEMOCRATIC WORLD Lisa Fleck Uhlir Yancy, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2008 APPROVED: Steven Forde, Major Professor Ken Godwin, Committee Member Richard Ruderman, Committee Member Milan Reban, Committee Member James Meernik, Chair of the Department of Political Science Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Yancy, Lisa Fleck Uhlir, Pride and sexual friendship: The battle of the sexes in Nietzsche’s post-democratic world. Doctor of Philosophy (Political Science), August 2008, 191 pp., bibliography of 227 titles. This dissertation addresses an ignored [partly for its controversial nature] aspect of Nietzschean philosophy: that of the role of modern woman in the creation of a future horizon. Details of the effects of the Enlightenment, Christianity and democracy upon society are discussed, as well as effects on the individual, particularly woman. After this forward look at the changes anticipated by Nietzsche, the traditional roles of woman as the eternal feminine, wife and mother are debated. An argument for the necessity of a continuation of the battle of the sexes, and the struggle among men and women in a context of sexual love and friendship is given. This mutual affirmation must occur through the motivation of pride and not vanity. In conclusion, I argue that one possible avenue for change is a Nietzschean call for a modern revaluation of values by noble woman in conjugation with her warrior scholar to bring about the elevation of mankind. -

Tommaso Campanella the Book and the Body of Nature Series: International Archives of the History of Ideas Archives Internationales D'histoire Des Idées

springer.com Germana Ernst Tommaso Campanella The Book and the Body of Nature Series: International Archives of the History of Ideas Archives internationales d'histoire des idées A comprehensive intellectual biography of an important and complex philosopher of the Renaissance A historical reconstruction of social and cultural relationships between the sixteenth and the seventeenth century A volume useful to clarify some philological and interpretative problems concerning modern editions and translations of Campanella’s texts A friend of Galileo and author of the renowned utopia The City of the Sun, Tommaso Campanella (Stilo, Calabria,1568- Paris, 1639) is one of the most significant and original thinkers of the early modern period. His philosophical project centred upon the idea of reconciling Renaissance philosophy with a radical reform of science and society. He produced a complex and articulate synthesis of all fields of knowledge – including magic and astrology. During his early formative years as a Dominican friar, he manifested a restless impatience 2010, XII, 281 p. towards Aristotelian philosophy and its followers. As a reaction, he enthusiastically embraced Bernardino Telesio’s view that knowledge could only be acquired through the observation of Printed book things themselves, investigated through the senses and based on a correct understanding of Hardcover the link between words and objects. Campanella’s new natural philosophy rested on the 139,99 € | £119.99 | $169.99 principle that the books written by men needed to be compared with God’s infinite book of [1]149,79 € (D) | 153,99 € (A) | CHF nature, allowing them to correct the mistakes scattered throughout the human ‘copies’ which 165,50 were always imperfect, partial and liable to revisions. -

Conversations with Stalin on Questions of Political Economy”

WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS Lee H. Hamilton, Conversations with Stalin on Christian Ostermann, Director Director Questions of Political Economy BOARD OF TRUSTEES: ADVISORY COMMITTEE: Joseph A. Cari, Jr., by Chairman William Taubman Steven Alan Bennett, Ethan Pollock (Amherst College) Vice Chairman Chairman Working Paper No. 33 PUBLIC MEMBERS Michael Beschloss The Secretary of State (Historian, Author) Colin Powell; The Librarian of Congress James H. Billington James H. Billington; (Librarian of Congress) The Archivist of the United States John W. Carlin; Warren I. Cohen The Chairman of the (University of Maryland- National Endowment Baltimore) for the Humanities Bruce Cole; The Secretary of the John Lewis Gaddis Smithsonian Institution (Yale University) Lawrence M. Small; The Secretary of Education James Hershberg Roderick R. Paige; (The George Washington The Secretary of Health University) & Human Services Tommy G. Thompson; Washington, D.C. Samuel F. Wells, Jr. PRIVATE MEMBERS (Woodrow Wilson Center) Carol Cartwright, July 2001 John H. Foster, Jean L. Hennessey, Sharon Wolchik Daniel L. Lamaute, (The George Washington Doris O. Mausui, University) Thomas R. Reedy, Nancy M. Zirkin COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES CHRISTIAN F. OSTERMANN, Series Editor This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. -

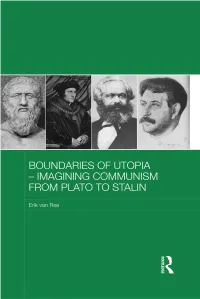

Boundaries of Utopia – Imagining Communism from Plato to Stalin

Boundaries of Utopia – Imagining Communism from Plato to Stalin The idea that socialism could be established in a single country was adopted as an official doctrine by the Soviet Union in 1925, Stalin and Bukharin being the main formulators of the policy. Before this there had been much debate as to whether the only way to secure socialism would be as a result of socialist revolution on a much broader scale, across all Europe or wider still. This book traces the development of ideas about communist utopia from Plato onwards, paying particular attention to debates about universalist ideology versus the possibility for ‘socialism in one country’. The book argues that although the prevailing view is that ‘socialism in one country’ was a sharp break from a long tradition that tended to view socialism as only possible if universal, in fact the territorially confined socialist project had long roots, including in the writings of Marx and Engels. Erik van Ree is an Assistant Professor at the Institute of European Studies at the University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Routledge Contemporary Russia and Eastern Europe Series 1 Liberal Nationalism in 7 The Telengits of Central Europe Southern Siberia Stefan Auer Landscape, religion and knowledge in motion 2 Civil-Military Relations in Agnieszka Halemba Russia and Eastern Europe David J. Betz 8 The Development of Capitalism in Russia 3 The Extreme Nationalist Simon Clarke Threat in Russia The growing influence of 9 Russian Television Today Western Rightist ideas Primetime drama and comedy Thomas Parland -

Tonini, Sandrine (2010) from Existentialist Anxiety to Existential

Tonini, Sandrine (2010) From existentialist anxiety to existential joy: gendered journeys towards (re)commitment in Les Mandarins and Il rimorso as evidence of Simone de Beauvoir's influence on Alba de Céspedes' writing. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2215/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] 1 From Existentialist Anxiety to Existential Joy: Gendered Journeys Towards (Re)commitment in Les Mandarins and Il rimorso as Evidence of Simone de Beauvoir’s Influence on Alba de Céspedes’ Writing Sandrine Tonini Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Modern Languages and Cultures French and Italian Sections Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow June 2010 2 Cette thèse est dédiée à ma mère qui éclaire le chemin, et à ma fille qui m’incite à le suivre. 3 Abstract Whilst Simone de Beauvoir has become an icon of feminism, and The Second Sex in particular been recognized as a point of reference for writers and philosophers worldwide, her reputation in Italy was not established immediately, and there she remains a controversial figure. -

Beauvoir on Gender, Oppression, and Freedom

24.01: Classics of Western Philosophy Beauvoir on Gender, Oppression, and Freedom 1. Introduction: Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986) Beauvoir was born in Paris and studied philosophy at the Sorbonne. She passed exams for Certificates in History of Philosophy, General Philosophy, Greek, and Logic in 1927, and in 1928, in Ethics, Sociology, and Psychology. She wrote a graduate diplôme (equivalent to an MA thesis) on Leibniz. Her peers included Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Claude Lévi-Strauss, and Jean-Paul Sartre. In 1929, she took second place in the highly competitive philosophy agrégation exam, barely losing to Jean-Paul Sartre who took first (it was his second attempt at the exam). At 21 years of age, Beauvoir was the youngest student ever to pass the exam. She taught in high school from 1929-1943, and then supported herself on her writings, and co-editorship of Le Temps Modernes. She is known for her literary writing, and her philosophical work in existentialism, ethics, and feminism. She published The Second Sex in 1949. 2. Gender ‘One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman. No biological, psychological or economic fate determines the future that the human female presents in society.’ (II.iv.1) A. What is a woman? “Tota mulier in utero: she is a womb,” some say. Yet speaking of certain women, the experts proclaim, “They are not women,” even though they have a uterus like the others. Everyone agrees there are females in the human species; today, as in the past, they make up about half of humanity; and yet we are told that “femininity is in jeopardy”; we are urged, “Be women, stay women, become women.” So not every female human being is necessarily a woman… (23) So there seems to be a sort of contradiction in our ordinary understanding of women: not every female is a woman, otherwise they would not be exhorted to be women. -

Foresight Hindsight

Hindsight, Foresight ThinkingI Aboutnsight, Security in the Indo-Pacific EDITED BY ALEXANDER L. VUVING DANIEL K. INOUYE ASIA-PACIFIC CENTER FOR SECURITY STUDIES HINDSIGHT, INSIGHT, FORESIGHT HINDSIGHT, INSIGHT, FORESIGHT Thinking About Security in the Indo-Pacific Edited by Alexander L. Vuving Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies Hindsight, Insight, Foresight: Thinking About Security in the Indo-Pacific Published in September 2020 by the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, 2058 Maluhia Rd, Honolulu, HI 96815 (www.apcss.org) For reprint permissions, contact the editors via [email protected] Printed in the United States of America Cover Design by Nelson Gaspar and Debra Castro Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Name: Alexander L. Vuving, editor Title: Hindsight, Insight, Foresight: Thinking About Security in the Indo-Pacific / Vuving, Alexander L., editor Subjects: International Relations; Security, International---Indo-Pacific Region; Geopolitics---Indo-Pacific Region; Indo-Pacific Region JZ1242 .H563 2020 ISBN: 978-0-9773246-6-8 The Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies is a U.S. Depart- ment of Defense executive education institution that addresses regional and global security issues, inviting military and civilian representatives of the United States and Indo-Pacific nations to its comprehensive program of resident courses and workshops, both in Hawaii and throughout the Indo-Pacific region. Through these events the Center provides a focal point where military, policy-makers, and civil society can gather to educate each other on regional issues, connect with a network of committed individuals, and empower themselves to enact cooperative solutions to the region’s security challenges. -

Sos Political Science & Public Administration M.A.Political Science

Sos Political science & Public administration M.A.Political Science II Sem Political Philosophy:Mordan Political Thought, Theory & contemporary Ideologies(201) UNIT-IV Topic Name-Utopian Socialism What is utopian society? • A utopia is an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its citizens.The opposite of a utopia is a dystopia. • Utopia focuses on equality in economics, government and justice, though by no means exclusively, with the method and structure of proposed implementation varying based on ideology.According to Lyman Tower SargentSargent argues that utopia's nature is inherently contradictory, because societies are not homogenous and have desires which conflict and therefore cannot simultaneously be satisfied. • The term utopia was created from Greek by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book Utopia, describing a fictional island society in the south Atlantic Ocean off the coast of South America Who started utopian socialism? • Charles Fourier was a French socialist who lived from 1772 until 1837 and is credited with being an early Utopian Socialist similar to Robert Owen. He wrote several works related to his socialist ideas which centered on his main idea for society: small communities based on cooperation Definition of utopian socialism • socialism based on a belief that social ownership of the means of production can be achieved by voluntary and peaceful surrender of their holdings by propertied groups What is the goal of utopian societies? • The aim of a utopian society is to promote the highest quality of living possible. The word 'utopia' was coined by the English philosopher, Sir Thomas More, in his 1516 book, Utopia, which is about a fictional island community. -

Norton Anthology of Western Philosophy: After Kant Table of Contents

NORTON ANTHOLOGY OF WESTERN PHILOSOPHY: AFTER KANT TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 1: The Interpretive Tradition Preface Acknowledgments GENERAL INTRODUCTION PROLOGUE Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) "What is Enlightenment?" (Translated by Lewis White Beck) From Critique of Pure Reason, Preface (Translated by Norman Kemp Smith) From Critique of Practical Reason, Conclusion (Translated by Lewis White Beck) I. IDEALISMS: SPIRITUALITY AND REALITY Introduction Friedrich Schiller (1759–1805) From On the Aesthetic Education of Man Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762–1814) From Science of Knowledge (Translated by Peter Heath and John Lachs) From Vocation of Man (Translated by William Smith) Friedrich Schelling (1775–1854) From Ideas for a Philosophy of Nature (Translated by Errol E. Harris and Peter Heath) From Of Human Freedom (Translated by James Gutmann) Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) Introductions On Philosophy: From The Encyclopedia of Philosophical [Wissenschaften] (Translated by William Wallace) On Philosophy and “Phenomenology”: From Phenomenology of [Geist] (Translated by J. B. Baillie) On Philosophical “Logic”: From The [Wissenschaft] of Logic (Encyclopedia, part 1) (Translated by William Wallace) On Nature: From Philosophy of Nature (Encyclopedia, part 2) (Translated by A. V. Miller) On the History of Philosophy: From Lectures on the History of Philosophy (Translated by E. S. Haldane) On History and Geist: From Lectures on the Philosophy of History (Translated by J. Sibree) On Geist: From Philosophy of [Geist] (Encyclopedia, part 3) (Translated by William Wallace and A. V. Miller) Subjective Geist 2 On Subjective (and Intersubjective) Geist: From Philosophy of [Geist] (Translated by William Wallace and A. V. Miller) On Consciousness and Self-Consciousness: From Phenomenology of [Geist] (Translated by J. -

Philosophy of Mind

Introduction to Philosophy: Philosophy of Mind INTRODUCTION TO PHILOSOPHY: PHILOSOPHY OF MIND ERAN ASOULIN, PAUL RICHARD BLUM, TONY CHENG, DANIEL HAAS, JASON NEWMAN, HENRY SHEVLIN, ELLY VINTIADIS, HEATHER SALAZAR (EDITOR), AND CHRISTINA HENDRICKS (SERIES EDITOR) Rebus Community Introduction to Philosophy: Philosophy of Mind by Eran Asoulin, Paul Richard Blum, Tony Cheng, Daniel Haas, Jason Newman, Henry Shevlin, Elly Vintiadis, Heather Salazar (Editor), and Christina Hendricks (Series Editor) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. CONTENTS What is an open textbook? vii Christina Hendricks How to access and use the books ix Christina Hendricks Introduction to the Series xi Christina Hendricks Praise for the Book xiv Adriano Palma Acknowledgements xv Heather Salazar and Christina Hendricks Introduction to the Book 1 Heather Salazar 1. Substance Dualism in Descartes 3 Paul Richard Blum 2. Materialism and Behaviorism 10 Heather Salazar 3. Functionalism 19 Jason Newman 4. Property Dualism 26 Elly Vintiadis 5. Qualia and Raw Feels 34 Henry Shevlin 6. Consciousness 41 Tony Cheng 7. Concepts and Content 49 Eran Asoulin 8. Freedom of the Will 58 Daniel Haas About the Contributors 69 Feedback and Suggestions 72 Adoption Form 73 Licensing and Attribution Information 74 Review Statement 76 Accessibility Assessment 77 Version History 79 WHAT IS AN OPEN TEXTBOOK? CHRISTINA HENDRICKS An open textbook is like a commercial textbook, except: (1) it is publicly available online free of charge (and at low-cost in print), and (2) it has an open license that allows others to reuse it, download and revise it, and redistribute it. -

Michael Schumann Hoffnung PDS Reden, Aufsätze, Entwürfe 1989–2000 Rls 12 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Texte 12 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung

Wolfram Adolphi (Hrsg.) Michael Schumann Hoffnung PDS Reden, Aufsätze, Entwürfe 1989–2000 rls 12 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Texte 12 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung WOLFRAM ADOLPHI (HRSG.) Michael Schumann Hoffnung PDS Reden, Aufsätze, Entwürfe 1989-2000 Mit einem Geleitwort von Lothar Bisky Karl Dietz Verlag Berlin Herausgegeben mit Unterstützung der PDS-Fraktion im Landtag Brandenburg. Ein besonderer Dank gilt Herrn Marco Schumann, Potsdam, für seine Hilfe und Mitarbeit. Wolfram Adolphi (Hrsg.): Michael Schumann. Hoffnung PDS Reden, Aufsätze, Entwürfe 1989-2000. Mit einem Geleitwort von Lothar Bisky (Reihe: Texte/Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung; Bd. 12) Berlin: Dietz, 2004 ISBN 3-320-02948-7 © Karl Dietz Verlag Berlin GmbH 2004 Satz: Jörn Schütrumpf Umschlag, Druck und Verarbeitung: MediaService GmbH BärenDruck und Werbung Printed in Germany Inhalt LOTHAR BISKY Zum Geleit 9 WOLFRAM ADOLPHI Vorwort 11 Abschnitt 1 Zum Herkommen und zur Entwicklung der PDS Wir brechen unwiderruflich mit dem Stalinismus als System! Referat auf dem Außerordentlichen Parteitag der SED in Berlin am 16. Dezember 1989 33 Von der SED zur PDS – geht die Rechnung auf? Interview für die Tageszeitung »Neues Deutschland« vom 26. Januar 1990 57 Programmatik und politisches System Artikel für die vom PDS-Parteivorstand herausgegebene Zeitschrift »Disput«, Heft 14/1992 (2. Juliheft) 69 Souverän mit unserer politischen Biographie umgehen Referat auf dem 3. Parteitag der PDS in Berlin (19.-21. Januar 1993) 74 Der Logik des Kräfteverhältnisses stellen! Rede auf dem 12. Parteitag der DKP, Gladbeck, am 13. November 1993 90 5 Vor fünf Jahren: »Wir brechen unwiderruflich mit dem Stalinismus als System!« Reminiszenzen und aktuelle Überlegungen 94 Antikommunismus? Schlußwort auf dem Historisch-rechtspolitischen Kolloquium »KPD-Verbot oder mit Kommunisten leben? Das KPD-Verbotsurteil des Bundesverfassungsgerichts vom 17. -

Women's Rights: Forbidden Subject

1 WOMEN’S RIGHTS: FORBIDDEN SUBJECT © Pexel.com CONTENTSI Introduction 3 1. Covering women’s rights can kill 4 Miroslava Breach and Gauri Lankesh, journalists who provoked 4 Murdered with impunity 7 2. A range of abuses to silence journalists 8 The figures 8 Elena Milashina – price on her head 9 Online threats 10 3. Leading predators 12 Radical Islamists 12 Pro-life 14 Organized crime 15 4. Authoritarian regimes 17 Judicial harassment in Iran 17 Government blackout 19 Still off limits despite legislative progress 21 5. Shut up or resist 25 Exile when the pressure is too much 25 Resistant voices 26 Interview with Le Monde reporter Annick Cojean 28 Recommendations 30 © RSF © NINTRODUCTIONN “Never forget that a political, economic or religious crisis would suffice to call women’s rights into question,” Simone de Beauvoir wrote in The Second Sex. Contemporary developments unfortunately prove her right. In the United States, outraged protests against President Donald Trump’s sexist remarks erupted in early 2017. In Poland, a bill banning abortion, permitted in certain circumstances since 1993, was submitted to parliament in 2016. In Iraq, a bill endangering women’s rights that included lowering the legal age for marriage was presented to the parliament in Baghdad the same year. Covering women’s issues does not come without danger. A female editor was murdered for denouncing a sexist policy. A reporter was imprisoned for interviewing 3 a rape victim. A woman reporter was physically attacked for defending access to tampons, while a female blogger was threatened online for criticizing a video game.