Agrarian Reform and the Slave System: a Case Study of James Galt's Point of Fork Plantation, 1835-1865

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Image Credits, the Making of African

THE MAKING OF AFRICAN AMERICAN IDENTITY: VOL. I, 1500-1865 PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION The Making of African American Identity: Vol. I, 1500-1865 IMAGE CREDITS Items listed in chronological order within each repository. ALABAMA DEPT. of ARCHIVES AND HISTORY. Montgomery, Alabama. WEBSITE Reproduced by permission. —Physical and Political Map of the Southern Division of the United States, map, Boston: William C. Woodbridge, 1843; adapted to Woodbridges Geography, 1845; map database B-315, filename: se1845q.sid. Digital image courtesy of Alabama Maps, University of Alabama. ALLPORT LIBRARY AND MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS. State Library of Tasmania. Hobart, Tasmania (Australia). WEBSITE Reproduced by permission of the Tasmanian Archive & Heritage Office. —Mary Morton Allport, Comet of March 1843, Seen from Aldridge Lodge, V. D. Land [Tasmania], lithograph, ca. 1843. AUTAS001136168184. AMERICAN TEXTILE HISTORY MUSEUM. Lowell, Massachusetts. WEBSITE Reproduced by permission. —Wooden snap reel, 19th-century, unknown maker, color photograph. 1970.14.6. ARCHIVES OF ONTARIO. Toronto, Ontario, Canada. WEBSITE In the public domain; reproduced courtesy of Archives of Ontario. —Letter from S. Wickham in Oswego, NY, to D. B. Stevenson in Canada, 12 October 1850. —Park House, Colchester, South, Ontario, Canada, refuge for fugitive slaves, photograph ca. 1950. Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, F2076-16-6. —Voice of the Fugitive, front page image, masthead, 12 March 1854. F 2076-16-935. —Unidentified black family, tintype, n.d., possibly 1850s; Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, F 2076-16-4-8. ASBURY THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY. Wilmore, Kentucky. Permission requests submitted. –“Slaves being sold at public auction,” illustration in Thomas Lewis Johnson, Twenty-Eight Years a Slave, or The Story of My Life in Three Continents, 1909, p. -

Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 0 MB No 1024-0018 (R11v. Aug. 2002) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This fo1m 1s for use m nomlnatino or r911ues\ing det.ormln"Ot.ons for 1nd ..wu111 ~ies ooo dtsmas see tnslTvQJons In How to CompJele I/le NaliOfl'al Register of Hl~onc Plncos R()9'sfrQ/lon Fom, (Nauonal Reglsler f3ulleun 16A). Compl11te ooch llem t>y mark1119 • (' ,,, th~ appmpr101e tx>ic 01 by eniertng ine 1mo11narion ruqut:Stect It any Item doc,!> nol ctpply to 11\e !)foe>efty be!OQ documeoiea. enrer "NIN for ·not appllcabln • For functions, archllecturol das~lfrcabon m111c,wls . 1111tJ areas of signtflcaoce, entef onlyca1esones ana subcategones from lhe1ns1n1cuons. Placeaddtuonai i,(lbie<- ar,d nana11,-e11oms O"\ conUnuooon :lheets (NPS Form 10-000a} Use-a 1ypew,,1e·. wore processor. or comput~r. to c:omolele all items =~"""""~-~--==:;::~=-================================================================================ 1. Name of Property =-===-========:r::=:::::==:::c:: ___ c:::=--- ------""-~--=c:::::-::::========================:======================= 2. Location not for publication__ x_ c,ly or town r----------------- vicinity N/A state Virginia code _V_A__ county Suny code ----21p code--- =-==== =:d======== ==-::====-=-=-=-====-====------------------====== 3. State/Federal Agency Certification ====-=,..-- ---- ------ As lhe designated authOnty under lhe Nallonal Hlstonc PraseMttron Act as amef'lded. I nereby cart.lfy that this~ nom1na11on __ request ror determination or eligibillly meets the documeotaUoo standards for registenng properties rn the National Register of Histonc Places and meets tne procedural and professlonat requirements set rorth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my Clpinion Uie proper;y .JS,_, meots __ does no1 meet the Natlonal Rag1s1ar Crtterm. -

The Slavery of Emancipation

University at Buffalo School of Law Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1996 The Slavery of Emancipation Guyora Binder University at Buffalo School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Guyora Binder, The Slavery of Emancipation, 17 Cardozo L. Rev. 2063 (1996). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles/301 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SLAVERY OF EMANCIPATION Guyora Binder* I. THE CLAIM: MANUMISSION IS NOT ABOLITION The Thirteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution com- mands that "neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall exist."' What has been the effect of this command? It will serve my present purpose to offer the following too- simple answer to this complex question: the Thirteenth Amend- ment secured little more than the manumission of slaves already practically freed by the friction of war. It guaranteed, in Confeder- ate General Robert Richardson's now well-known phrase, "noth- 2 ing but freedom." Supposing this answer to be true, a further question presents itself: Did the Thirteenth Amendment's effect fulfill its command? Did universal manumission abolish slavery? A full answer to this question would require a rich historical account of the evolving institution of American slavery, the fea- tures of that institution that survived the Reconstruction era, and how those features evolved in the ensuing century and a quarter. -

Slaves at the University of Virginia

Gayle M. Schulman, an avocational local historian, conducted this research during the early months of 2003 and presented it to the African American Genealogy Group of Charlottesville/ Albemarle in May of that year. Her interest in this topic grew from her research on Isabella Gibbons (a teacher who spent part of her life as a slave on the grounds of the University of Virginia) and the community in which she lived. This essay is an overview of the information collected from vital statistics, census data, church records, University of Virginia Archives, and faculty manuscripts. A more extensive research project on the same topic is currently being conducted by Catherine Neale, a student at the University of Virginia. [2005] Slaves at the University of Virginia Gayle M. Schulman1 There is no sign of the vegetable garden, hen house, well, or the outbuildings once on the land. The rear of the three-storied house, glimpsed through the trees, is partially masked by boxwoods. On the lower level of the garden one passes an English Gothic pinnacle to find steps up to a gate through a serpentine wall into an upper garden; there one can see the home’s second story door with a handsome transom window like half of a daisy, or perhaps a fine piece of oriental embroidery. Tucked beneath the steep stairways to this grand back entry is a solid door leading into the cellar. The oldest part of this cellar is divided by a central chimney that is flanked by two rooms on one side and a larger room, the original kitchen, on 2 the other. -

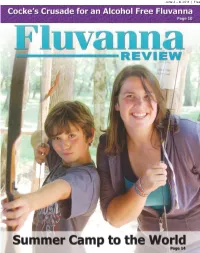

June 2 – 8, 2011 | Free June 2 – 8, 2011 • Volume 31, Issue 22 Fluvanna This Week in Review

June 2 – 8, 2011 | Free JUNE 2 – 8, 2011 • VOLUME 31, ISSUE 22 Fluvanna This week in review... REVIEW www.fluvannareview.com Publisher/Editor: Carlos Santos [email protected] Financing Skaters Advertising Manager: Evelyn Inskeep fences succeed [email protected] Accounts Manager: Diane Eliason [email protected] page page Advertising Designer: Lisa Hurdle [email protected] 7 8 Web Administrator/Designer: Kathy Zeek [email protected] Designer: Marilyn Ellinger Staff Writers: Page Gifford, Jennifer Zajac, Duncan Nixon, O.T. Holen, Joe Ronan, Kristin Sancken, Ruthann Carr and Tammy Purcell Long way to Hat’s off Photographers: David Stemple, O.T. Holen Fluvanna Mailing Address: P.O. Box 59, Palmyra, VA 22963 Address: 2987 Lake Monticello Road page page Phone: (434) 591-1000 Fax: (434) 589-1704 12 16 Member of the Virginia Press Association General: Fluvanna Review is published weekly Deadline: Advertising due Wednesday 5 p.m. News hotline: 434-207-0224. If you see news by Valley Publishing Corp. Founded in 1979, for the following week. happening, call us! it’s the only paper that covers Fluvanna exclu- Display and web ads: For information in- sively. One copy is free. Additional copies are Submissions, tips, ideas, etc.: the Fluvanna cluding rates and deadlines, call Lisa Hurdle $1 each payable in advance to the at 434-591-1000 ext. 29. Review encourages submissions and tips on publisher. items of interest to Fluvanna residents. We re- Legal ads: the Fluvanna Review is the paper of serve the right to edit submissions and cannot Subscriptions: Copies record for Fluvanna County. Call Lisa Hurdle guarantee they will be published. -

Thinking About Slavery at the College of William and Mary

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 21 (2012-2013) Issue 4 Article 6 May 2013 Thinking About Slavery at the College of William and Mary Terry L. Meyers Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Repository Citation Terry L. Meyers, Thinking About Slavery at the College of William and Mary, 21 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 1215 (2013), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol21/iss4/6 Copyright c 2013 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj THINKING ABOUT SLAVERY AT THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY Terry L. Meyers* I. POST-RECONSTRUCTION AND ANTE-BELLUM Distorting, eliding, falsifying . a university’s memory can be as tricky as a person’s. So it has been at the College of William and Mary, often in curious ways. For example, those delving into its history long overlooked the College’s eighteenth century plantation worked by slaves for ninety years to raise tobacco.1 Although it seems easy to understand that omission, it is harder to understand why the College’s 1760 affiliation with a school for black children2 was overlooked, or its president in 1807 being half-sympathetic to a black man seeking to sit in on science lectures,3 or its awarding an honorary degree to the famous English abolitionist Granville Sharp in 1791,4 all indications of forgotten anti-slavery thought at the College. To account for these memory lapses, we must look to a pivotal time in the late- nineteenth and early-twentieth century when the College, Williamsburg, and Virginia * Chancellor Professor of English, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia, [email protected]. -

Pavilion Vii

PAVILION VII HISTORY AUTHORIZATION AND NEGOTIATION FOR CONSTRUCTING PAVILION VII he germ of the plan of Pavilion VII can be detected in a letter Jefferson wrote to Virginia Legislator Littleton Waller Tazewell on January 5, 1805, from the Presi- T dent's House in Washington 1. In his letter, which was in response to an inquiry concerning a proposal for a university that Tazewell wished to submit to the General As- sembly, Jefferson wrote: Large houses are always ugly, inconvenient, exposed to the accident of fire, and bad in case of infection. A plain small house for the school & lodging of each professor is best, these connected by covered ways out of which the rooms of the students should open. These may then be built only as they shall be wanting. In fact a university should not be a house but a village. 2 Nothing came of Tazewell's proposal, but five years later Jefferson had the occa- sion to refine his ideas when he responded to another inquiry, this time from Hugh White, a trustee of the East Tennessee College: I consider the common plan followed in this country of making one large and expensive building, as unfortunately erroneous. It is infinitely better to erect a small and separate lodge for each separate professorship, with only a hall below for his class, and two chambers above for himself; joining these lodges by bar- racks for a certain portion of the students, opening into a covered way to give a dry communication between all the schools. The whole of these arranged around an open square of grass and trees, would make it, what it should be in fact, an academical village. -

Old Courthouse Poster

John Hartwell Cocke Soldier, Reformer, Friend to Thomas Jefferson Member of the Founding Board of Visitors of the University of Virginia John Hartwell Cocke and Thomas Jefferson shared many interests in spite of a 37-year gap in age and temperamental differences. Both were educated at the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, and valued learning, knowledge, and books. Cocke was instrumental in helping establish, build, and govern the University of Virginia in Charlottesville as the realization of Jefferson’s vision and design. Born in 1870 in Surry County in eastern Virginia and raised there, Cocke married Ann Blaws Barraud in 1802. Seven years later, Cocke moved his family to inherited land grant property in Fluvanna County along the James River where he would develop Bremo Plantation. A distinguished soldier, during the War of 1812 Cocke was commissioned a brigadier general. Soon after relocation to Fluvanna, Cocke began a friendship with his older neighbor Thomas Jefferson of Monticello in nearby Albemarle County. Both men owned vast lands and believed in agricultural experimentation and innovation. They traded seed stock, plants and horses, shared agricultural information, and pursued the substitution of crops to replace tobacco—a crop that caused depletion of soil and was heavily dependent on enslaved labor. Practical and disciplined, Cocke was also a reformer who embraced temperance, a devout Christian and a philanthropist. After the 1816 death of Anne, his first wife and mother of their six children, Cocke became evangelical and a member and officer of the Virginia Society for the Promotion of Temperance. In 1821, Cocke married widow Louisa Maxwell Holmes from Norfolk. -

A Rational Society of Gardeners

2007 MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL SOCIETY Jefferson’s Horticultural Neighborhood: A Rational Society of Gardeners HOMAS JEFFERSON is regarded as the “from dinner to dark I give to society and Tessential cerebral figure in American recreation with my neighbors and friends.” history. As well, he was so immersed One of the central themes that defined in public life, his family, farms, and a Jefferson’s interest in gardening was staggering world of outside interests that the union of gardening and sociability. his consistent search and cultivation of Jefferson used plants and gardens as a way personal friendships is a surprising facet of relating to friends, family, neighbors; of his personality. Jefferson wrote that even political allies. A thread of garden “Agreeable society is the first essential in gossip weaves its way through the letters constituting the happiness and of course published in Thomas Jefferson’s Garden the value of our existence.” He referred to Book, as Jefferson would preface letters on friendships as a “rational society” which the future of the American republic with “informs the mind, sweetens the temper, a discussion of how his gardens fared at cheers our spirits, and promotes health.” Monticello. Plants, from the golden rain This was expressed early in Jefferson’s tree obtained from seed from Lafayette’s youth and his close friendships with aunt, Madame de Tessé, to the geranium boyhood pals like John Page, William houseplant Jefferson offered to the Fleming, and Robert Skipwith. This Washington socialite, Margaret Bayard rational society based on a warm and open Smith, were tangible tokens of friendship. intellectual commerce was experienced by Jefferson’s granddaughter, Ellen Randolph Jefferson in Williamsburg with George Coolidge, recalled the heyday of flower Wythe, Governor Francis Fauquier, gardening at Monticello: Jefferson, his and William Small. -

Download a PDF Version of the Guide to African American Manuscripts

Guide to African American Manuscripts In the Collection of the Virginia Historical Society A [Abner, C?], letter, 1859. 1 p. Mss2Ab722a1. Written at Charleston, S.C., to E. Kingsland, this letter of 18 November 1859 describes a visit to the slave pens in Richmond. The traveler had stopped there on the way to Charleston from Washington, D.C. He describes in particular the treatment of young African American girls at the slave pen. Accomack County, commissioner of revenue, personal property tax book, ca. 1840. 42 pp. Mss4AC2753a1. Contains a list of residents’ taxable property, including slaves by age groups, horses, cattle, clocks, watches, carriages, buggies, and gigs. Free African Americans are listed separately, and notes about age and occupation sometimes accompany the names. Adams family papers, 1698–1792. 222 items. Mss1Ad198a. Microfilm reels C001 and C321. Primarily the papers of Thomas Adams (1730–1788), merchant of Richmond, Va., and London, Eng. Section 15 contains a letter dated 14 January 1768 from John Mercer to his son James. The writer wanted to send several slaves to James but was delayed because of poor weather conditions. Adams family papers, 1792–1862. 41 items. Mss1Ad198b. Concerns Adams and related Withers family members of the Petersburg area. Section 4 includes an account dated 23 February 1860 of John Thomas, a free African American, with Ursila Ruffin for boarding and nursing services in 1859. Also, contains an 1801 inventory and appraisal of the estate of Baldwin Pearce, including a listing of 14 male and female slaves. Albemarle Parish, Sussex County, register, 1721–1787. 1 vol. -

Walking Tour of Historic 16

Beginning Your Tour… the construction of the courthouse, including hauling and Village Tour Map installing the huge stone steps. It is one of only a few In Civil War Park stands a tall granite spire monument antebellum courthouses to retain its original form without dedicated by the Daughters of the Confederacy in additions or changes to its interior arrangement. The building 1901. Two bronze Union Civil War cannons added in 1909 served as an operating room during the Civil War. flank the monument. A large granite stone and plaque dedicated in 2019 commemorate President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863. NOTICE: Private properties are not open to the public. Interior tours are offered for the Old Stone Jail and the Historic Courthouse. VILLAGE CENTER (Green Tour) 2. The present-day Fluvanna County Courthouse was at one time the site of Reverend Walker Timberlake’s Palmyra House. Built as his home in 1825, it once served as a tavern. It burned down in 1941. 3. The site of Reverend Walker Timberlake’s 1836 Hotel and Tavern is on the present lawn of the county government complex. The hotel, which burned in 1908, was rebuilt by Ashby Haden and later became a residence, apartments and government offices. In 1972 the structure was removed for a new county office building. The Acropolis of Palmyra 4. The two-story section of Maggie’s House was built circa 1854 and expanded with subsequent additions. A post office 9. In 1835 Abram Shepherd, the Court Clerk, paid to build was once located on the north side of the building with a the Clerk’s Office when the county was unable to afford separate entrance. -

1 Board of Historic Resources Quarterly Meeting 21 June 2018

Board of Historic Resources Quarterly Meeting 21 June 2018 Sponsor Markers - Diversity 1.) School for Black Children Sponsor: College of William & Mary Locality: Williamsburg Proposed Location: 107 North Boundary St. on the campus of William & Mary Sponsor Contact: Susan Kern, [email protected]; Michael J. Fox, [email protected] Original text: School for Black Children A school for enslaved and free black children was founded here in 1760 by the Associates of Dr. Bray, a London charity. At Benjamin Franklin’s urging, the school was affiliated with the College of William & Mary. In a culture hostile to educating blacks, boys and girls were taught Christianity and “some useful Things besides Reading” and, possibly, writing. Ann Wager tutored over 400 children during her 14 years as teacher. The school moved to other locations after 1765 and closed in 1774. The teachings at the school reinforced ideologies supporting slavery, but also spread literacy within the black community. 100 words/ 617 characters Edited text: School for Black Children The Associates of Dr. Bray, a London-based charity, founded a school for enslaved and free black children here in 1760. Located in Williamsburg at the suggestion of Benjamin Franklin, a member of the Associates, the school received support from the College of William & Mary. Anne Wager instructed as many as 400 boys and girls during her 14 years as teacher. In a culture hostile to educating African Americans, Wager taught the students principles of Christianity, deportment, reading, and, possibly, writing. The curriculum reinforced proslavery ideology but also spread literacy within the black community. The school moved from this site by 1765 and closed in 1774.