Conceptions of Humanity in Three Works of Post-Apocalyptic Fiction Bachelor’S Diploma Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Od Dżumy Do Eboli Sposób Przedstawienia Wybranych Chorób Zaraźliwych W Przykładowych Tekstach Literatury Popularnej

Od dżumy do Eboli Sposób przedstawienia wybranych chorób zaraźliwych w przykładowych tekstach literatury popularnej Od dżumy do Eboli Sposób przedstawienia wybranych chorób zaraźliwych w przykładowych tekstach literatury popularnej Edyta Izabela Rudolf Pracownia Literatury i Kultury Popularnej oraz Nowych Mediów Wrocław 2019 Seria „POPkultura – POPliteratura” Redaktor serii: Anna Gemra Recenzja naukowa: Monika Brzóstowicz-Klajn, Adam Mazurkiewicz Adiustacja, korekta: Zofia Smyk Projekt graficzny: Michał Wolski Skład, łamanie, projekt okładki: Agata Ceckowska Zdjęcie na okładce: Marta Nowakowska W składzie wykorzystano krój pisma Minion Pro Roberta Slimbacha. Tytuł został złożony krojem Ubuntu Daltona Maaga. Druk: Sowa-Druk na Życzenie www.sowadruk.pl tel. 022 431–81–40 © Copyright by Pracownia Literatury i Kultury Popularnej oraz Nowych Mediów ISBN: 978-83-94-66562-3 Pracownia Literatury i Kultury Popularnej oraz Nowych Mediów Instytut Filologii Polskiej Uniwersytet Wrocławski pl. Nankiera 15b 50–140 Wrocław Spis treści Wprowadzenie 7 O epidemii – rozważania na temat definicji 8 Medycyna, historia, kultura 10 Literatura contra epidemia 19 Między plagą a epidemiologią 33 Część I. Zanim odkryto zarazek 33 Antyk 33 Dziennik roku zarazy 35 Wieki średnie 36 Wiek XIX: Ostatni człowiek 39 Maski śmierci 58 Mikroskopijni sojusznicy 69 Część II. Wiek XX: wiek zdarzeń 73 Ostatni świadek 73 Podsumowanie 79 Mikroby ze światów swoich i obcych 85 Śmierć nadejdzie z nieba – lata siedemdziesiąte XX wieku 87 „Andromeda” znaczy śmierć 102 Podsumowanie 112 -

Download Ebook ^ Moon-Face and Other Stories

MM9JVTXJWSBE Book ~ Moon-Face and Other Stories (Dodo Press) (Paperback) Moon-Face and Oth er Stories (Dodo Press) (Paperback) Filesize: 4.04 MB Reviews Great eBook and beneficial one. It is packed with wisdom and knowledge You wont really feel monotony at at any time of your respective time (that's what catalogs are for relating to if you check with me). (Maiya Kozey) DISCLAIMER | DMCA EYPY4T5EDMT6 ~ Doc \\ Moon-Face and Other Stories (Dodo Press) (Paperback) MOON-FACE AND OTHER STORIES (DODO PRESS) (PAPERBACK) To download Moon-Face and Other Stories (Dodo Press) (Paperback) PDF, remember to access the web link below and save the ebook or have access to other information which are related to MOON-FACE AND OTHER STORIES (DODO PRESS) (PAPERBACK) book. Dodo Press, United Kingdom, 2007. Paperback. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****.Jack London (1876-1916), was an American author and a pioneer in the then-burgeoning world of commercial magazine fiction. He was one of the first Americans to make a lucrative career exclusively from writing. London was self-educated. He taught himself in the public library, mainly just by reading books. In 1898, he began struggling seriously to break into print, a struggle memorably described in his novel, Martin Eden (1909). Jack London was fortunate in the timing of his writing career. He started just as new printing technologies enabled lower-cost production of magazines. This resulted in a boom in popular magazines aimed at a wide public, and a strong market for short fiction. In 1900, he made $2,500 in writing, the equivalent of about $75,000 today. -

Pandemic Fear and Literature

Pandemic Fear and Literature: Observations from Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague [Announcer] This program is presented by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention The Scarlet Plague, originally published by Jack London in 1912, was one of the first examples of a post-apocalyptic fiction novel in modern literature. Set in a ravaged and wild America, the story takes place in 2073, sixty years after the spread of the Red Death, an uncontrollable epidemic that depopulated and nearly destroyed the world of 2013. One of the few survivors, James Howard Smith, alias “Granser,” tells his incredulous and near-savage grandsons how the pandemic spread in the world and about the reactions of the people to contagion and death. Even though it was published more than a century ago, The Scarlet Plague feels contemporary because it allows modern readers to reflect on the worldwide fear of pandemics, a fear that remains very much alive. By exploring the motif of the plague, a consistent and well-spread theme in literature, London’s novel is part of a long literary tradition, inviting the reader to reflect on the ancestral fear of humans toward infectious diseases. In the ancient world, plague and pestilence were rather frequent calamities, and ordinary people were likely to have witnessed or heard vivid and scary reports about their terrible ravages. When plague spread, no medicine could help, and no one could stop it from striking; the only way to escape was to avoid contact with infected people and contaminated objects. The immense fright was also fueled by a belief in the supernatural origin of pandemics, which were often believed to be provoked by offenses against divinities. -

ABSTRACT Jack London Is Not Just an Author of Dog Stories. He Is

UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA ABSTRACT Jack London is not just an author of dog stories. He is according to some literary critics, one of the greatest writers in the world. His stories are read worldwide more than any other American author, alive or dead, and he is considered by many as the American finest author. This work presents Jack London as a man who is valiant, wise, adventurous, a good worker, and a dreamer who tries to achieve his goals. He shows that poverty is not an obstacle to get them. His youth experiences inspire him to create his literary works. His work exemplifies traditional American values and captures the spirit of adventure and human interest. His contribution to literature is great. We can find in his collection of works a large list of genders like AUTORAS: María Eugenia Cabrera Espinoza Carmen Elena Soto Portuguéz 1 UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA novels, short stories, non-fiction, and autobiographical memoirs. These genders contain a variety of literary styles, adventure, drama, suspense, humor, and even romance. Jack London gets the materials of his books from his own adventures; his philosophy was a product of his own experiences; his love of life was born from trips around the world and voyages across the sea. Through this work we can discover that the key of London's greatness is universality that is his work is both timely and timeless. Key Words: Life, Literature, Work, Contribution, Legacy. AUTORAS: María Eugenia Cabrera Espinoza Carmen Elena Soto Portuguéz 2 UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA INDEX ACKNOWLEDGMENTS DEDICATIONS INDEX ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION CHAPTER ONE: JACK LONDON´S BIOGRAPHY 1.1 Childhood 1.2 First success 1.3 Marriage 1.4 Death CHAPTER TWO: WORKS 2.1 Short stories 2.2 Novels 2.3 Non-fiction and Autobiographical Memoirs 2.4 Drama AUTORAS: María Eugenia Cabrera Espinoza Carmen Elena Soto Portuguéz 3 UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA CHAPTER THREE: ANALYSIS OF ONE OF LONDON´S WORKS 1.1 “The Call of the Wild 1.2 Characters 1.3 Plot 1.4 Setting CHAPTER FOUR: LONDON´S LEGACY 1. -

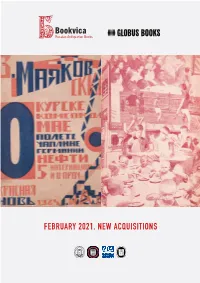

February 2021. New Acquisitions F O R E W O R D

FEBRUARY 2021. NEW ACQUISITIONS F O R E W O R D Dear friends & colleagues, We are happy to present our first catalogue of the year in which we continue to study Russian and Soviet reality through books, magazines and other printed materials. Here is a list of contents for your easier navigation: ● Architecture, p. 4 ● Women Studies, p. 19 ● Health Care, p. 25 ● Music, p. 34 ● Theatre, p. 40 ● Mayakovsky, p. 49 ● Ukraine, p. 56 ● Poetry, p. 62 ● Arctic & Antarctic, p. 66 ● Children, p. 73 ● Miscellaneous, p. 77 We will be virtually exhibiting at Firsts Canada, February 5-7 (www.firstscanada.com), andCalifornia Virtual Book Fair, March 4-6 (www.cabookfair.com). Please join us and other booksellers from all over the world! Stay well and safe, Bookvica team February 2021 BOOKVICA 2 Bookvica 15 Uznadze St. 25 Sadovnicheskaya St. 0102 Tbilisi Moscow, RUSSIA GEORGIA +7 (916) 850-6497 +7 (985) 218-6937 [email protected] www.bookvica.com Globus Books 332 Balboa St. San Francisco, CA 94118 USA +1 (415) 668-4723 [email protected] www.globusbooks.com BOOKVICA 3 I ARCHITECTURE 01 [HOUSES FOR THE PROLETARIAT] Barkhin, G. Sovremennye rabochie zhilishcha : Materialy dlia proektirovaniia i planovykh predpolozhenii po stroitel’stvu zhilishch dlia rabochikh [i.e. Contemporary Workers’ Dwellings: Materials for Projecting and Planned Suggestions for Building Dwellers for Workers]. Moscow: Voprosy truda, 1925. 80 pp., 1 folding table. 23x15,5 cm. In original constructivist wrappers with monograph MB. Restored, pale stamps of pre-war Worldcat shows no Ukrainian construction organization on the title page, pp. 13, 45, 55, 69, copies in the USA. -

Seawolf Press Announces the Publication of the Jack London 100Th Anniversary Collection

Contact: For Robert Etheredge Immediate Release [email protected] 925-255-3728 February 14, 2018 SeaWolf Press Announces the Publication of the Jack London 100th Anniversary Collection ORINDA, CA – February 14, 2018 - SeaWolf Press is proud to announce the comple- tion of the publication of all 50 books from the well-known American author Jack London. The 100th Anniversary Collection honors Jack London’s death in 1916. The text and illustrations are taken from the fi rst editions, and the covers are replicas of the fi rst edition covers. Jack London’s Life Jack London lived a life of extremes while becoming the best known author in the world. Raised in a working class family in Oakland, California, he was primarily self-taught. His adventurous life provided material for his stories, articles, and books. Known for his realistic writing, his life experiences are revealed in every book. He spent time as a teenage oyster pirate on San Francisco Bay, sailed on a sealing schooner, train-hopped the country as a hobo, scrambled for gold in the Klondike, sailed the Pacific, and was heavily involved in socialism. His dream house in Glen Ellen burned to the ground the day it was finished. A well-known Socialist, his death was observed by a cease-fire for a day during the Russian Revolution. Wide range of subjects The collection highlights the wide range of subjects that London wrote about during his life- time. He fi rst gained fame for his stories of the Klondike gold rush, such as “Call of the Wild” and “White Fang”. -

SPECIAL COLLECTIONS: Inventory

SPECIAL COLLECTIONS: Inventory UNIVERSITY LIBRARY n SONOMA STATE UNIVERSITY n library.sonoma.edu Jack London Collection Pt. 1 Box and Folder Inventory Photocopies of collection materials 1. Correspondence 2. First Appearances: Writings published in magazines 3. Movie Memorabilia (part 1) 4. Documents 5. Photographs and Artwork 6. Artifacts 7. Ephemera 8. Miscellaneous Materials Related to Jack London 9. Miscellaneous Materials Related to Carl Bernatovech Pt. 2 Box and Folder Inventory Additional materials 1. Published books: First editions and variant editions, some with inscriptions. 2. Movie Memorabilia (part 2) Series 1 – Correspondence Twenty-six pieces of correspondence are arranged alphabetically by author then sub-arranged in chronological order. The majority of the correspondence is from Jack and Charmian London to Mr. Wiget, the caretaker of their ranch in Glen Ellen, or to Ed and Ida Winship. The correspondence also includes one love letter from Jack to Charmian. Series 2 – First Appearances: Writings published in magazines Magazines often provided the first appearances of Jack London’s short stories and novels in serialized form. For example, The Call of the Wild first appeared in the Saturday Evening Post in June of 1903. It was then published later that same year by the Macmillan Company. Studying first appearances in magazines gives the researcher the opportunity to analyse textual changes that occurred over time and provides an opportunity to view the original illustrations. In several instances, Jack London specifically chose the illustrator for his stories. The collection contains two hundred and thirty-seven of Jack London’s magazine publications, both fiction and non-fiction, including many first appearances. -

After the Plague: Society in Selected Post-Apocalyptic Novels

After the Plague: Society in Selected Post-Apocalyptic Novels Pavel Mrva Bachelor’s Thesis 2018/2019 ABSTRAKT Tato bakalářská práce zkoumá společnost ve čtyřech zvolených literárních dílech post- apokalyptické beletrie: The Scarlet Plague (Rudý mor) Jacka Londona, Earth Abides George R. Stewarta, Some Will Not Die Algise Budryse a Summer of the Apocalypse Jamese Van Pelta. Cílem práce je najít podobnosti a rozdíly mezi těmito díly, přičemž se zaměřuje na kolaps společenského řádu, vznik nového společenského řádu a změny v kultuře společnosti v jednotlivých románech. Dochází k závěru, že ve všech zkoumaných románech jsou přítomny jevy jako zločin a návrat k divošství, jenž často vede ke vzniku kmenových společností. Klíčová slova: společnost, post-apokalyptická beletrie, The Scarlet Plague, Rudý mor, Jack London, Earth Abides, George R. Stewart, Some Will Not Die, Algis Budrys, Summer of the Apocalypse, James Van Pelt, kolaps společenského řádu, nový společenský řád, kultura, zločin, divošství, kmenová společnost ABSTRACT The bachelor’s thesis examines society in four selected literary works of post-apocalyptic fiction: The Scarlet Plague by Jack London, Earth Abides by George R. Stewart, Some Will Not Die by Algis Budrys and Summer of the Apocalypse by James Van Pelt. The thesis aims to find similarities and differences among these works with regard to the collapse of social order, an emergence of a new social order and the changes in the culture of each society in each of the selected novels. It comes to the conclusion that phenomena such as crime and reversion to savagery, which often results in a formation of tribal societies, are present in all the examined novels. -

The Scarlet Plague

^,>%mjr^m- \J JlTL K^ ^ JL^'o/^e4||ib^ CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE Digitized by Microsoft® __ Cornell University Library PS 3523.058S2 3 1924 021 764 158 Digitized by Microsoft® This book was digitized by Microsoft Corporation in cooperation witli Cornell University Library, 2008. You may use and print this copy in limited quantity for your personal purposes, but may not distribute or provide access to it (or modified or partial versions of it) for revenue-generating or other commercial purposes. Digitized by Microsoft® THE SCARLET PLAGUE Digitized by Microsoft® THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK • BOSTON • CHICAGO - DALLAS ATLANTA • SAN FRANCISCO MACMILLAN & CO., Limited LONDON BOMBAY CALCUTTA MELBOURNE THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd. TORONTO Digitized by Microsoft® Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tlie Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924021764158 Digitized by Microsoft® ALL THE WORLD SEEMED y'ltAPPED IN FLAMES Digitized by Microsoft® The Scarlet Plague BY JACK LONDON AUTHOR OF "THE SEA WOLF," "THE CALL OF THE WILD," "THE MUTINY OF THE ELSINORE," ETC. ILLUSTRATED BY GORDON GRANT Tgtin gatfe THE MACMILLAN COMPANY All fights reserved Digitized by Microsoft® Copyright, 1912, By jack LONDON. Copyright, 1913, By the star CO. Copyright, 1915, By jack LONDON. Set up and electrotyped. Published May, 19x5. I^otiiiooti $ngg J. S. Gushing Oo. — Berwick & Smith Co. Norwood, Mass., IT.S.A. Digitized by Microsoft® THE SCARLET PLAGUE Digitized by Microsoft® Digitized by Microsoft® Digitized by Microsoft® Digitized by Microsoft® THE SCARLET PLAGUE I THE way led along upon what had once been the embankment of a railroad. -

Jack London's Works by Date of Composition

Jack London's Works by Date of Composition By James Williams The following chronological listing is an aid to further research in London studies. Used with other sources it becomes a powerful means to clarify the obscurities and confusions surrounding London's writing career. The rationale for including the following titles is two-fold. First, all novels and all stories listed in Russ Kingman, "A Collector's Guide to Jack London" have been included. I chose Kingman's list rather than Woodbridge's bibliography because the former is easier to use for this purpose and is as reliable as the latter. In addition, stories, sketches, and poems appear in the following list that were not published by London but are significant because they give us a fuller idea of the nature of London's work at a particular time. This is especially true for the first years of his writing. A few explanations concerning the sources are necessary. I have been conservative in my approximations of dates that cannot be pinpointed exactly. If, for example, a story's date of composition cannot be verified, and no reliable circumstantial evidence exists, then I have simply given its date of publication. Publication dates are unreliable guides for composing dates and can be used only as the latest possible date that a given story could have been written. One may find out if the date given is a publication date simply by checking to see if the source is Woodbridge, the standard London bibliography. If the source used is JL 933-935, then the date is most likely the earliest date London sent the manuscript to a publisher. -

Verdens Undergang (1916) and the Birth of Apocalyptic Film: Antecedents and Causative Forces Wynn Gerald Hamonic Thompson Rivers University, [email protected]

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 20 Article 30 Issue 3 October 2016 10-2-2016 Verdens Undergang (1916) and the Birth of Apocalyptic Film: Antecedents and Causative Forces Wynn Gerald Hamonic Thompson Rivers University, [email protected] Recommended Citation Hamonic, Wynn Gerald (2016) "Verdens Undergang (1916) and the Birth of Apocalyptic Film: Antecedents and Causative Forces," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 20 : Iss. 3 , Article 30. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol20/iss3/30 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Verdens Undergang (1916) and the Birth of Apocalyptic Film: Antecedents and Causative Forces Abstract This essay describes the antecedents and causative forces giving rise to the birth of apocalyptic cinema in the early 20th Century and the first apocalyptic feature, Verdens Undergang (1916). Apocalyptic cinema's roots can be traced back to apocalyptic literary tradition beginning 200 BCE, New Testament apocalyptic writings, the rise of premillenialism in the mid-19th Century, 19th century apocalyptic fiction, a growing distrust in human self-determination, escalating wars and tragedies from 1880 to 1912 reaching a larger audience through a burgeoning press, horrors and disillusionment caused by the First World War, a growing belief in a dystopian future, and changes in the film industry. Keywords Verdens Undergang, Apocalypse, Motion Pictures, Antecedents, Causes, Danish Film Author Notes Wynn Hamonic is Subject Matter Expert and Curriculum Consultant for Film 3991: Cinematic Visions of the Apocalypse, at Thompson Rivers University, Kamloops, B.C., Canada. -

Pandemic Fear and Literature: Observations from Jack London's

Pandemic Fear and Literature: Observations from Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague Michele Augusto Riva,1 Marta Benedetti,1 and Giancarlo Cesana he Scarlet Plague, originally published by Jack In contrast, the Greek historian Thucydides (c. 460– TLondon in 1912, was one of the first examples of 395 BCE), in his History of the Peloponnesian War, and the a postapocalyptic fiction novel in modern literature (1). Latin poet Lucretius (c. 99–55 BCE), in his De Rerum Natu- Set in a ravaged and wild America, the story takes place ra, refuted a supernatural origin of the disease and focused in 2073, sixty years after the spread of the Red Death, their descriptions on the uncontrolled fear of contagion an uncontrollable epidemic that depopulated and nearly among the public. According to these authors, plague did destroyed the world in 2013. One of the few survivors, not discriminate between the good and the evil but brought James Howard Smith, alias “Granser,” tells his incred- about the loss of all social conventions and a rise in selfish- ulous and near-savage grandsons how the pandemic ness and avarice. spread in the world and about the reactions of the people Later medieval writings, such as The Decameron by to contagion and death. Even though it was published Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375) and The Canterbury Tales more than a century ago, The Scarlet Plague feels con- by Geoffrey Chaucer (1343–1400), emphasized human be- temporary because it allows modern readers to reflect havior: the fear of contagion increased vices such as avarice, on the worldwide fear of pandemics, a fear that remains greed, and corruption, which paradoxically led to infection very much alive.