The Effects of Increasing Visitor and Noise Levels on Birds Within a Free-Flight Aviary Examined Through Enclosure Use and Behavior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

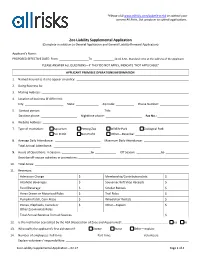

Zoo Liability Supplemental Application (Complete in Addition to General Application and General Liability Renewal Application)

*Please visit www.allrisks.com/submit-a-risk or contact your current All Risks, Ltd. producer to submit applications. Zoo Liability Supplemental Application (Complete in addition to General Application and General Liability Renewal Application) Applicant’s Name: PROPOSED EFFECTIVE DATE: From To 12:01 A.M., Standard Time at the address of the Applicant PLEASE ANSWER ALL QUESTIONS—IF THEY DO NOT APPLY, INDICATE “NOT APPLICABLE” APPLICANT PREMISES OPERATIONS INFORMATION 1. Named Insured as it is to appear on policy: 2. Doing Business As: 3. Mailing Address: 4. Location of business (if different): City: State: Zip Code: Phone Number: 5. Contact person: Title: Daytime phone: Nighttime phone: Fax No.: 6. Website Address: 7. Type of Institution: Aquarium Petting Zoo Wildlife Park Zoological Park For Profit Non Profit Other—Describe: 8. Average Daily Attendance: Maximum Daily Attendance: Total Annual Attendance: 9. Hours of Operations: In Season: to Off Season: to Describe off-season activities or promotions: 10. Total Acres: 11. Revenues: Admission Charge $ Membership/Contributions/etc. $ Alcoholic Beverages $ Souvenier/Gift Shop Receipts $ Food/Beverage $ Stroller Rentals $ Horse Drawn or Motorized Rides $ Trail Rides $ Pumpkin Patch, Corn Maze $ Wheelchair Rentals $ Ponies, Elephants, Camels or $ Other—Explain: $ Other Zoo Animals Rides Total Annual Revenue from all Sources $ 12. Is the institution accredited by the AZA (Association of Zoos and Aquariums)? ........................................................ Yes No 13. Who staffs the applicant’s first aid station? Doctor Nurse Other—explain: 14. Number of employees: Full-time: Part-time: Volunteers: Explain volunteers’ responsibilities: Zoo Liability Supplemental Application – 02.17 Page 1 of 4 Do volunteers sign waivers of liability? ........................................................................................................................ -

Vancouver, British Columbia Destination Guide

Vancouver, British Columbia Destination Guide Overview of Vancouver Vancouver is bustling, vibrant and diverse. This gem on Canada's west coast boasts the perfect combination of wild natural beauty and modern conveniences. Its spectacular views and awesome cityscapes are a huge lure not only for visitors but also for big productions, and it's even been nicknamed Hollywood North for its ever-present film crews. Less than a century ago, Vancouver was barely more than a town. Today, it's Canada's third largest city and more than two million people call it home. The shiny futuristic towers of Yaletown and the downtown core contrast dramatically with the snow-capped mountain backdrop, making for postcard-pretty scenes. Approximately the same size as the downtown area, the city's green heart is Canada's largest city park, Stanley Park, covering hundreds of acres filled with lush forest and crystal clear lakes. Visitors can wander the sea wall along its exterior, catch a free trolley bus tour, enjoy a horse-drawn carriage ride or visit the Vancouver Aquarium housed within the park. The city's past is preserved in historic Gastown with its cobblestone streets, famous steam-powered clock and quaint atmosphere. Neighbouring Chinatown, with its weekly market, Dr Sun Yat-Sen classical Chinese gardens and intriguing restaurants add an exotic flair. For some retail therapy or celebrity spotting, there is always the trendy Robson Street. During the winter months, snow sports are the order of the day on nearby Grouse Mountain. It's perfect for skiing and snowboarding, although the city itself gets more rain than snow. -

A Toolkit to Engage in Field Conservation

A Toolkit to Engage in Field Conservation created by the AZA Field Conservation Committee 3rd Edition, December 2018 Dear colleagues, As an accredited or certified related facility of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, the mission of your organization is rooted in conservation. This means that regardless of your role at the organization, your job includes helping to save wildlife and wild places. You also likely know what is happening to animals and plants in the wild and that many scientists believe we are experiencing Earth’s sixth mass extinction. This means we all need to do our job of saving wildlife and wild places better, and this toolkit can help us meet the challenge. The content included in this toolkit focuses on overcoming the obstacles that stop us from helping animals and plants in the wild - like a limited budget, or a governing body resistant to spending funds on efforts outside the facility. This toolkit is neither a primer on the threats facing wildlife nor does it explore methodologies to implement conservation in the field, develop conservation education programs that lead to changed behaviors, reduce the use of natural resources in business operations or conduct scientific research that may ultimately inform conservation, as resources for those important issues are available elsewhere. As an AZA member, you know the power of collaboration. What we can do together can have a profound impact in our communities and around the world. Already, the AZA community spends more than $200 million each year on field conservation with a direct impact on animals and habitats in the wild. -

South Africa: Magoebaskloof and Kruger National Park Custom Tour Trip Report

SOUTH AFRICA: MAGOEBASKLOOF AND KRUGER NATIONAL PARK CUSTOM TOUR TRIP REPORT 24 February – 2 March 2019 By Jason Boyce This Verreaux’s Eagle-Owl showed nicely one late afternoon, puffing up his throat and neck when calling www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | TRIP REPORT South Africa: Magoebaskloof and Kruger National Park February 2019 Overview It’s common knowledge that South Africa has very much to offer as a birding destination, and the memory of this trip echoes those sentiments. With an itinerary set in one of South Africa’s premier birding provinces, the Limpopo Province, we were getting ready for a birding extravaganza. The forests of Magoebaskloof would be our first stop, spending a day and a half in the area and targeting forest special after forest special as well as tricky range-restricted species such as Short-clawed Lark and Gurney’s Sugarbird. Afterwards we would descend the eastern escarpment and head into Kruger National Park, where we would make our way to the northern sections. These included Punda Maria, Pafuri, and the Makuleke Concession – a mouthwatering birding itinerary that was sure to deliver. A pair of Woodland Kingfishers in the fever tree forest along the Limpopo River Detailed Report Day 1, 24th February 2019 – Transfer to Magoebaskloof We set out from Johannesburg after breakfast on a clear Sunday morning. The drive to Polokwane took us just over three hours. A number of birds along the way started our trip list; these included Hadada Ibis, Yellow-billed Kite, Southern Black Flycatcher, Village Weaver, and a few brilliant European Bee-eaters. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible. -

At the Dallas World Aquarium Silver-Beaked, Blue-Gray, and Palm Tanagers Can Be Heard More Readily by Shelly Nice, Dallas, TX Than Seen in the Rainforest

ignored with live palm trees being pre Birds ferred. This is probably due to all of the live vegetation. at the Dallas World Aquarium Silver-beaked, Blue-gray, and Palm Tanagers can be heard more readily by Shelly Nice, Dallas, TX than seen in the rainforest. Although he Dallas World Aquarium, the other birds. When food is first intro once you hear then1 they are easily no longer just a place to see duced, it is the smaller birds like the seen. They eat a variety of fruits, fish, is celebrating the first Black -necked and the Green Aracari worms, and seeds. They will stay T that eat first - before the larger toucans together or close by each other. anniversary of a pennanent South Alnerican rainforest exhibit. The pri fly in to eat. Even larger birds such as Although they are the last ones to eat vately owned aquarium allows visitors a curassows will wait for the toucans to fruit, they will be the first ones to arrive glimpse of the flora and fauna from eat before getting their share. when food is put out in the morning. places that many may never see in per , Nesting is another story. The nesting They will perch with toucans just a foot son, such as Lord Howe Island, Banggai sites of the Black-necked Aracari are away and wait their tum. Periodically I land, and Venezuela. The aquarium taken over by the Keel-billed, regard one of these birds will disappear, but it contains several large exhibits of marine less of location. -

A Classification of the Rallidae

A CLASSIFICATION OF THE RALLIDAE STARRY L. OLSON HE family Rallidae, containing over 150 living or recently extinct species T and having one of the widest distributions of any family of terrestrial vertebrates, has, in proportion to its size and interest, received less study than perhaps any other major group of birds. The only two attempts at a classifi- cation of all of the recent rallid genera are those of Sharpe (1894) and Peters (1934). Although each of these lists has some merit, neither is satisfactory in reflecting relationships between the genera and both often separate closely related groups. In the past, no attempt has been made to identify the more primitive members of the Rallidae or to illuminate evolutionary trends in the family. Lists almost invariably begin with the genus Rdus which is actually one of the most specialized genera of the family and does not represent an ancestral or primitive stock. One of the difficulties of rallid taxonomy arises from the relative homo- geneity of the family, rails for the most part being rather generalized birds with few groups having morphological modifications that clearly define them. As a consequence, particularly well-marked genera have been elevated to subfamily rank on the basis of characters that in more diverse families would not be considered as significant. Another weakness of former classifications of the family arose from what Mayr (194933) referred to as the “instability of the morphology of rails.” This “instability of morphology,” while seeming to belie what I have just said about homogeneity, refers only to the characteristics associated with flightlessness-a condition that appears with great regularity in island rails and which has evolved many times. -

Review of the Status of Introduced Non-Native Waterbird Species in the Area of the African-Eurasian Waterbird Agreement: 2007 Update

Secretariat provided by the Workshop 3 United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Doc TC 8.25 21 February 2008 8th MEETING OF THE TECHNICAL COMMITTEE 03 - 05 March 2008, Bonn, Germany ___________________________________________________________________________ Review of the Status of Introduced Non-Native Waterbird Species in the Area of the African-Eurasian Waterbird Agreement: 2007 Update Authors A.N. Banks, L.J. Wright, I.M.D. Maclean, C. Hann & M.M. Rehfisch February 2008 Report of work carried out by the British Trust for Ornithology under contract to AEWA Secretariat © British Trust for Ornithology British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk IP24 2PU Registered Charity No. 216652 CONTENTS Page No. List of Tables...........................................................................................................................................5 List of Figures.........................................................................................................................................7 List of Appendices ..................................................................................................................................9 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..................................................................................................................11 RECOMMENDATIONS .....................................................................................................................13 1. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................15 -

The Gambia: a Taste of Africa, November 2017

Tropical Birding - Trip Report The Gambia: A Taste of Africa, November 2017 A Tropical Birding “Chilled” SET DEPARTURE tour The Gambia A Taste of Africa Just Six Hours Away From The UK November 2017 TOUR LEADERS: Alan Davies and Iain Campbell Report by Alan Davies Photos by Iain Campbell Egyptian Plover. The main target for most people on the tour www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] p.1 Tropical Birding - Trip Report The Gambia: A Taste of Africa, November 2017 Red-throated Bee-eaters We arrived in the capital of The Gambia, Banjul, early evening just as the light was fading. Our flight in from the UK was delayed so no time for any real birding on this first day of our “Chilled Birding Tour”. Our local guide Tijan and our ground crew met us at the airport. We piled into Tijan’s well used minibus as Little Swifts and Yellow-billed Kites flew above us. A short drive took us to our lovely small boutique hotel complete with pool and lovely private gardens, we were going to enjoy staying here. Having settled in we all met up for a pre-dinner drink in the warmth of an African evening. The food was delicious, and we chatted excitedly about the birds that lay ahead on this nine- day trip to The Gambia, the first time in West Africa for all our guests. At first light we were exploring the gardens of the hotel and enjoying the warmth after leaving the chilly UK behind. Both Red-eyed and Laughing Doves were easy to see and a flash of colour announced the arrival of our first Beautiful Sunbird, this tiny gem certainly lived up to its name! A bird flew in landing in a fig tree and again our jaws dropped, a Yellow-crowned Gonolek what a beauty! Shocking red below, black above with a daffodil yellow crown, we were loving Gambian birds already. -

ON 24(1) 35-53.Pdf

ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 24: 35–53, 2013 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society CONTRIBUTION OF DIFFERENT FOREST TYPES TO THE BIRD COMMUNITY OF A SAVANNA LANDSCAPE IN COLOMBIA Natalia Ocampo-Peñuela1,2 & Andrés Etter1 1Departamento de Ecología y Territorio, Facultad de Estudios Ambientales y Rurales - Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá DC, Colombia. E-mail: [email protected] 2Nicholas School of the Environment, Box 90328, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708, USA. Resumen. – Contribución de diferentes tipos de bosque a la comunidad de aves en un paisaje de sabana en Colombia. – La heterogeneidad del paisaje es particularmente importante en paisajes frag- mentados, donde cada fragmento contribuye a la biodiversidad del paisaje. Este aspecto ha sido menos estudiado en paisajes naturalmente fragmentados, comparado con aquellos fragmentados por activ- idades antrópicas. Estudiamos las sabanas de la región de la Orinoquia en Colombia, un paisaje natural- mente fragmentado. El objetivo fue determinar la contribución de tres tipos de bosque de un mosaico de bosque-sabana (bosque de altillanura, bosques riparios anchos, bosques riparios angostos), a la avi- fauna del paisaje. Nos enfocamos en la estructura de la comunidad de aves, analizando la riqueza de especies y la composición de los gremios tróficos, las asociaciones de hábitat, y la movilidad relativa de las especies. Usando observaciones, grabaciones, y capturas con redes de niebla, registramos 109 especies. Los tres tipos del paisaje mostraron diferencias importantes, y complementariedad con respecto a la composición de las aves. Los análisis de gremios tróficos, movilidad, y asolación de hábitat reforzaron las diferencias entre los tipos de bosque. El bosque de altillanura presentó la mayor riqueza de aves, y a la vez también la mayor cantidad de especies únicas.