The Bali Paradox: Best of Both Worlds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ministerial Understanding on Asean

G UNDERSTANDIN L MINISTERIA M TOURIS N I N COOPERATIO N ASEA N O WE the undersigned, attending the Meeting of ASEAN Tourism Ministers (M-ATM) held in Mactan, Cebu, Philippines on 10 January 1998; RECALLING the : 1. Declaration of ASEAN Concord signed in Bali, Indonesia on 24 February 1976, which stated that Member States shall take cooperative action in their national and regional development programmes, to broaden the complementarity of their respective economies; 2. Manila Declaration of 1987 signed on 15 December 1987, which expressed that ASEAN shall encourage intra-ASEAN travel and develop a viable and competitive tourist industry; 3. Singapore Declaration of 1992 signed on 28 January 1992, which expressed that ASEAN shall continue with its concerted efforts in the promotion of tourism; 4. Framework Agreement on Enhancing ASEAN Economic Cooperation signed on 28 January 1992 provided that Member States agree to increase cooperation in tourism promotion; and 1 5. The Bangkok Summit Declaration of 1995 signed on 15 December 1995 : that s other g amon d state h whic (a) ASEAN shall focus on promoting sustainable tourism development, preservation of cultural and environmental resources, the provision of transportation and other infrastructure, simplification of immigration procedures and human resource development; (b) ASEAN shall continue to support sub-regional arrangements; e trad r free d an n cooperatio g enhancin s toward e mov l shal N ASEA ) (c in services to include tourism, through the implementation of the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Services; and (d) ASEAN Sectoral Ministers as well as Senior Officials shall meet regularly to embark on new initiatives to strengthen economic c Economi r Senio e th d an s Minister c Economi N ASEA . -

The Emergence of Political Homophobia in Indonesia 465 the Emergence of Political Homophobia in Indonesia: Masculinity and National Belonging

The Emergence of Political Homophobia in Indonesia 465 The Emergence of Political Homophobia in Indonesia: Masculinity and National Belonging Tom Boellstorff University of California, Irvine, USA abstract This paper explores an unprecedented series of violent acts against ‘gay’ Indonesians beginning in September 1999. Indonesia is often characterized as ‘to- lerant’ of homosexuality. This is a false belief, but one containing a grain of truth. To identify this grain of truth I distinguish between ‘heterosexism’ and ‘homophobia,’ noting that Indonesia has been marked by a predominance of heterosexism over homophobia. I examine the emergence of a political homophobia directed at public events where gay men stake a claim to Indonesia’s troubled civil society. That such violence is seen as the properly masculine response to these events indicates how the nation may be gaining a new masculinist cast. In the new Indonesia, male–male desire can increasingly be construed as a threat to normative masculinity, and thus to the nation itself. keywords Homosexuality, Indonesia, emotion, violence, masculinity n November 11, 2000, about 350 gay and male-to-female transvest- ite (waria, banci, béncong) Indonesians gathered in the resort town of Kaliurang in Central Java for an evening of artistic performances O 1 and comedy skits. The event, in observance of National Health Day, was sponsored by several health organizations as well as the local France-Indonesia Institute: many heterosexual or normal Indonesians also attended. Events like this have been held across Indonesia since the early 1990s, and those present had no reason to suspect this night would be any different. However, at around 9:30 p.m. -

Marianas Variety Vol. 24, No. 207, 1995-12-29.Pdf

UNiVERcr~' o··"' ·-, · · ·· · .. ,, .,_. ' J? .. .... _, , .,-· ,; r -"'"- ? • ' . I 7· , ,-::...___--i,ML_.:..=......__ "lJ-~ ...,l,,,;;;.1,,J,J.,l" ' !.....:.-/~.,.___,i·:.n.._~---- ar1 an as %riet.r,:~ Micronesia's Leading Newspaper Since 1972 - ~~ ea By Ferdie de la Torre Coldeen had .been detained Variety News Staff Police looking into suicide angle since Dec. 13 when he was ar AN INMATE was found dead rested for creating disturbance at hanging inside his cell at the De showed that while Taitano, one of Public Safety Information Of <;:oldeen was alone in his cell. their house while reportedly parunent of Public Safety yester the detention officers, was con ficer Cathy Sheu said they could A reliable source said a shoe drunk. day morning. ducting a routine check up of the not release the cause of death lace was used. Although Coldeen was not for Police Officer Joseph Taitano detention facility he saw Coldeen pending an autopsy. DPS Commissioner Jose M. mally charged in connection with discovered the body of Alexander hanging. Sheu said investigators, who Castro neither confirmed nor de that incident, the Superior Court David Coldecn, 24, of Navy Hill, Emergency medical technicians are still looking into the case, did nied it. He said the case was still remanded him back to police cus at 7 a.m. transported Coldeen to the Com not disclose what instrument was under investigation. tody for violating the terms and Initial police investigations monwealth Health Center. used in hanging. Castro, however, pointed out conditions of his release in a pre that inmates are not allowed to vious criminal case. -

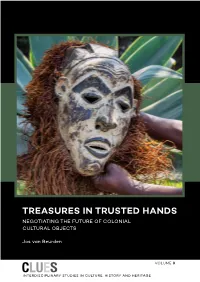

Treasures in Trusted Hands

Van Beurden Van TREASURES IN TRUSTED HANDS This pioneering study charts the one-way traffic of cultural “A monumental work of and historical objects during five centuries of European high quality.” colonialism. It presents abundant examples of disappeared Dr. Guido Gryseels colonial objects and systematises these into war booty, (Director-General of the Royal confiscations by missionaries and contestable acquisitions Museum for Central Africa in by private persons and other categories. Former colonies Tervuren) consider this as a historical injustice that has not been undone. Former colonial powers have kept most of the objects in their custody. In the 1970s the Netherlands and Belgium “This is a very com- HANDS TRUSTED IN TREASURES returned objects to their former colonies Indonesia and mendable treatise which DR Congo; but their number was considerably smaller than has painstakingly and what had been asked for. Nigeria’s requests for the return of with detachment ex- plored the emotive issue some Benin objects, confiscated by British soldiers in 1897, of the return of cultural are rejected. objects removed in colo- nial times to the me- As there is no consensus on how to deal with colonial objects, tropolis. He has looked disputes about other categories of contestable objects are at the issues from every analysed. For Nazi-looted art-works, the 1998 Washington continent with clarity Conference Principles have been widely accepted. Although and perspicuity.” non-binding, they promote fair and just solutions and help people to reclaim art works that they lost involuntarily. Prof. Folarin Shyllon (University of Ibadan) To promote solutions for colonial objects, Principles for Dealing with Colonial Cultural and Historical Objects are presented, based on the 1998 Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art. -

Toward the Tallest Statue of Garuda Wisnu Kencana: an Exploration of the Architectonic Design of the Land Art of Nyoman Nuarta’S Work

International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology (IJCIET) Volume 8, Issue 11, November 2017, pp. 357–367, Article ID: IJCIET_08_11_038 Available online at http://http://www.iaeme.com/ijciet/issues.asp?JType=IJCIET&VType=8&IType=11 ISSN Print: 0976-6308 and ISSN Online: 0976-6316 © IAEME Publication Scopus Indexed TOWARD THE TALLEST STATUE OF GARUDA WISNU KENCANA: AN EXPLORATION OF THE ARCHITECTONIC DESIGN OF THE LAND ART OF NYOMAN NUARTA’S WORK Yuke Ardhiati Universitas Pancasila, Jakarta, Indonesia ABSTRACT The research is focused on land art of an eminent Indonesian artist, Nyoman Nuarta. He is an artist of the (next) tallest statue in the world named Garuda Wisnu Kencana (GWK) in 145 metres (1978-present) in Ungasan Bali. By referring to multi- disciplinary approach within a grounded theory of Glaser and Strauss (2010) in architectural research, it was revealed as a new architectonic of land art design as well as his mentalité-artistry. By investigating his works, it is defined three periods categorized of Nuarta’s land art in 1977-2017, among others: (a) ‘Jejak Sains’ (the Science’s Traced) period represent his sculpture’s knowledge and his ideology of Indonesian New Art Movement (Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru Indonesia) were revealed a new indonesian genre in modern sculpture integrated with land art project as investigated in the Presidential Sculpture Competition for Indonesia’s Proclamation of Independence Statue (Patung Proklamator Soekarno-Hatta) (1977-1978) in Proclamation Park (Taman Proklamasi) Jakarta, (b) ‘Jejak Teknologi’ -

Michael Malley

T he 7th D evelopment Cabinet: Loyal to a Fault? Michael Malley Five years ago, amid speculation that B. J. Habibie and his allies in the Association of Indonesian Muslim Intellectuals (ICMI) would gain a large number of seats in the cabinet, State Secretary Moerdiono announced that "expertise" would be Soeharto's chief criterion for choosing ministers. This year, despite the economic crisis that enveloped the country, few people even thought to suggest that Soeharto sought the most technically qualified assistants. As the outgoing cabinet's term wore to a close, the jockeying for influence among ministers and their would-be successors emphasized the most important qualification of any who would join the new cabinet: loyalty. As if to diminish any surprise at the lengths he would go to create a cabinet of loyalists, Soeharto fired his central bank chief, Soedradjad Djiwandono, in mid- February, just two weeks before the 6 ^ Development Cabinet's term expired. Together with the finance minister, Mar'ie Muhammad, Soedradjad had worked closely with the International Monetary Fund to reach the reform-for-aid agreements Soeharto signed in October 1997 and January this year. Their support for reforms that would strike directly at palace-linked business interests seems to have upset the president, and neither were expected to retain their posts in the 7 ^ Cabinet. But Soedradjad made the further mistake of opposing the introduction of a currency board system to fix the rupiah's value to that of the US dollar. The scheme's main Indonesian proponents were Fuad Bawazier, one of Mar'ie's subordinates, and Peter Gontha, the principal business adviser to Soeharto's son Bambang Trihatmodjo. -

Timmas36-7 95-06.Doc

Documents on East Timor from PeaceNet and Connected Computer Networks Double issue Volumes 36-37: March 13 - June 26, 1995 Published by: East Timor Action Network / U.S. P.O. Box 1182, White Plains, NY 10602 USA Tel: 914-428-7299 Fax: 914-428-7383 E-mail PeaceNet:CSCHEINER or [email protected] These documents are produced approximately every two months and mailed to subscribers. For additional or back copies, send US$25 per volume; add $3 for international air mail. Discount rates: $10 for educational and non-profit institutions; $6 for U.S. activists; $8 international. Subscription rates: $150 ($60 educational, $36 activist) for the next six issues. Add $18 ($12 activist) for international air mail. Further subsidies are available for groups in Third World countries working on East Timor. Checks should be made out to “ETAN.” The material is grouped by subject, with articles under each category in approximately chronological order. It is also available on IBM-compatible diskette, in either Word for Windows or ASCII format. Reprinting and distribution without permission is welcomed. Much of this information is translated and supplied by TAPOL and BCET (London), Task Force Indone- sia (USA), CDPM (Lisbon), CNRM, Free East Timor Japan Coalition, Mate-Bian News (Sydney), East Timor Ireland Solidarity Campaign, ETIC (Aotearoa), Australians for a Free East Timor (Darwin) and other activists and solidarity groups, but they are not responsible for edi torial comment or selection. TABLE OF CONTENTS HISTORICAL ISSUES................................................................................................................................. -

Information Highways : Policies and Regulations in Construction of Global Infrastructure in Asean

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Information highways : policies and regulations in construction of global infrastructure in Asean Naswil Idris 1998 Naswil I. (1998). Information highways : policies and regulations in construction of global infrastructure in Asean. In AMIC Conference on Information Highway: Policy and Regulation in the Construction of Global Infrastructure in ASEAN, Singapore, Nov 25‑27, 1998. Singapore: Asian Media Information and Communication Centre. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/93365 Downloaded on 10 Oct 2021 15:28:41 SGT ATTENTION: The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. Nanyang Technological University Library Paper No. 6 ATTENTION: The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. Nanyang Technological University Library FINAL DRAFT 25 October, 1998 INFORMATION HIGHWAYS: POLICIES AND REGULATIONS IN CONSTRUCTION OF GLOBAL INFRASTRUCTURE IN ASEAN CHAPTER I LITERATURE REVIEW (Summarized, compiles and quoted from Government Publication) By Naswil Idris Email: [email protected] / [email protected] The role of telecommunication in any countries at the beginning is to provide means for command and control of the power group or government. So does with Indonesia, telecommunication found in October the 3rd 1858, when the government of the Netherlands-Indies lined telegraph between Batavia (Now: Jakarta) and Buitenzorg (Now: Bogor) a city around 60 km south of Jakarta. The body that provides the duties a government body. Parallel with the development of human life, telecommunication role had moved and upgraded from the means of command and control to the means of interchanged information on any aspect of life. -

Vol III Komodo National Park, Indonesia

TOURISM, CONSERVATION & SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT VOLUME III KOMODO NATIONAL PARK, INDONESIA Final Report to the Department for International Development Principal Authors: Goodwin, H.J., Kent, I.J., Parker, K.T., & Walpole, M.J. Project Managers: Goodwin, H.J.(Project Director), Swingland, I.R., Sinclair, M.T.(to August 1995), Parker, K.T.(from August 1995) Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology (DICE), Institute of Mathematics and Statistics (IMS), University of Kent April 1997 This is one of four final reports produced at the end of a three year, Department for International Development funded project. Three case study reports (Vols. II-IV) present the research findings from the individual research sites (Keoladeo NP, India, Komodo NP, Indonesia, and the south-east Lowveld, Zimbabwe). The fourth report (Vol. I) contains a comparison of the findings from each site. Contextual data reports for each site, and methodological reports, were compiled at the end of the first and second years of the project respectively. The funding for this research was announced to the University of Kent by the ODA in December 1993. The original management team for the project consisted of, Goodwin, H.J., (Project Director), Swingland, I.R. and Sinclair, M.T. In August 1995, Sinclair was replaced by Parker, K.T. Principal Authors: • Dr Harold Goodwin (Project Director, DICE) • Mr Ivan Kent (DICE) • Dr Kim Parker (IMS) • Mr Matt Walpole (DICE) The collaborating institution in Indonesia was the Wallacea Development Institute (WDI). The research co-ordinators in Indonesia were Mr A.Karamoy (WDI) and Ir.Sudibyo (PHPA, Bogor). Research in Komodo National Park was overseen by the park director, Drs. -

On Tourism, Ethnic Negotiation and National Integration in Sulawesi Indonesia

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Anthropology: Faculty Publications and Other Works Faculty Publications 5-1997 Touting Touristic Primadonas: On Tourism, Ethnic Negotiation and National Integration in Sulawesi Indonesia Kathleen M. Adams Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/anthropology_facpubs Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Adams, K. "Touting touristic primadonas: on tourism, ethnic negotiation and national integration in Sulawesi Indonesia" in M Picard and R Woods eds. Tourism, Ethnicity, and the State in Asian and Pacific Societies (University of Hawai'i Press, 1997). This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © Kathleen M. Adams, 1997. picard.book Page 155 Monday, November 19, 2001 9:12 AM KATHLEEN M. ADAMS 6 Touting Touristic “Primadonas”: Tourism, Ethnicity, and National Integration in Sulawesi, Indonesia In 1980 Pierre van den Berghe observed that tourism is gen- erally superimposed on indigenous systems of ethnic relations and can profoundly affect indigenous ethnic hierarchies. Only recently, however, have Pacific scholars begun to explore seriously the salience of van den Berghe’s observations for countries promoting tourism as a strategy for nation-building (see Adams 1991, Kipp 1993, Picard 1993, Wood 1984). For instance, Wood (1984) discusses the politics of tourism in Southeast Asia, noting that a government’s promotion of tourism not only can heighten the cultural self-consciousness and ethnic pride of indigenous groups but also can suppress those groups that are not selected for the touristic map. -

Toward the Tallest Statue of Garuda Wisnu Kencana: an Exploration of the Architectonic Design of the Land Art of Nyoman Nuarta’S Work

International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology (IJCIET) Volume 8, Issue 11, November 2017, pp. 357–367, Article ID: IJCIET_08_11_038 Available online at http://http://iaeme.com/Home/issue/IJCIET?Volume=8&Issue=11 ISSN Print: 0976-6308 and ISSN Online: 0976-6316 © IAEME Publication Scopus Indexed TOWARD THE TALLEST STATUE OF GARUDA WISNU KENCANA: AN EXPLORATION OF THE ARCHITECTONIC DESIGN OF THE LAND ART OF NYOMAN NUARTA’S WORK Yuke Ardhiati Universitas Pancasila, Jakarta, Indonesia ABSTRACT The research is focused on land art of an eminent Indonesian artist, Nyoman Nuarta. He is an artist of the (next) tallest statue in the world named Garuda Wisnu Kencana (GWK) in 145 metres (1978-present) in Ungasan Bali. By referring to multi- disciplinary approach within a grounded theory of Glaser and Strauss (2010) in architectural research, it was revealed as a new architectonic of land art design as well as his mentalité-artistry. By investigating his works, it is defined three periods categorized of Nuarta’s land art in 1977-2017, among others: (a) ‘Jejak Sains’ (the Science’s Traced) period represent his sculpture’s knowledge and his ideology of Indonesian New Art Movement (Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru Indonesia) were revealed a new indonesian genre in modern sculpture integrated with land art project as investigated in the Presidential Sculpture Competition for Indonesia’s Proclamation of Independence Statue (Patung Proklamator Soekarno-Hatta) (1977-1978) in Proclamation Park (Taman Proklamasi) Jakarta, (b) ‘Jejak Teknologi’ (the Technology’s -

Adat and Indigeneity in Indonesia Culture and Entitlements Between Heteronomy and Self-Ascription

Adat and Indigeneity in Indonesia Culture and Entitlements between Heteronomy and Self-Ascription Brigitta Hauser-Schäublin (dir.) Publisher: Göttingen University Press Year of publication: 2013 Published on OpenEdition Books: 12 April 2017 Serie: Göttingen Studies in Cultural Property Electronic ISBN: 9782821875487 http://books.openedition.org Printed version ISBN: 9783863951320 Number of pages: 240 Electronic reference HAUSER-SCHÄUBLIN, Brigitta (ed.). Adat and Indigeneity in Indonesia: Culture and Entitlements between Heteronomy and Self-Ascription. New edition [online]. Göttingen: Göttingen University Press, 2013 (generated 10 septembre 2020). Available on the Internet: <http://books.openedition.org/gup/150>. ISBN: 9782821875487. © Göttingen University Press, 2013 Terms of use: http://www.openedition.org/6540 number of UN conventions and declarations (on the Rights of Indigenous 7 A Peoples, the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressi- Göttingen Studies in ons and the World Heritage Conventions) can be understood as instruments of Cultural Property, Volume 7 international governance to promote democracy and social justice worldwide. In Indonesia (as in many other countries), these international agreements have encouraged the self-assertion of communities that had been oppressed and de- Adat and Indigeneity in Indonesia prived of their land, especially during the New Order regime (1966-1998). More than 2,000 communities in Indonesia who define themselves asmasyarakat adat Culture and Entitlements between or “indigenous peoples” had already joined the Indigenous Peoples’ Alliance of Heteronomy and Self-Ascription the Archipelago” (AMAN) by 2013. In their efforts to gain recognition and self- determination, these communities are supported by international donors and Brigitta Hauser-Schäublin (ed.) international as well as national NGOs by means of development programmes.