Vol III Komodo National Park, Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Walk on the Wild Side

SCAPES Island Trail your chauffeur; when asked to overtake, he regards you with bewildered incomprehension: “Overtake?” Balinese shiftlessness and cerebral inertia exasperate, particularly the anguished Japanese management with their brisk exactitude at newly-launched Hoshinoya. All that invigorates Bali is the ‘Chinese circus’. Certain resort lobbies, Ricky Utomo of the Bvlgari Resort chuckles, “are like a midnight sale” pulsating with Chinese tourists in voluble haberdashery, high-heeled, almost reeling into lotus ponds they hazard selfies on. The Bvlgari, whose imperious walls and august prices discourage the Chinese, say they had to terminate afternoon tea packages (another Balinese phenomenon) — can’t have Chinese tourists assail their precipiced parapets for selfies. The Chinese wed in Bali. Indians honeymoon there. That said, the isle inspires little romance. In the Viceroy’s gazebo, overlooking Ubud’s verdure, a honeymooning Indian girl, exuding from her décolleté, contuses her anatomy à la Bollywood starlet, but her husband keeps romancing his iPhone while a Chinese man bandies a soft toy to entertain his wife who shuts tight her eyes in disdain as Mum watches on in wonderment. When untoward circumstances remove us to remote and neglected West Bali National Park, where alone on the island you spot deer, two varieties, extraordinarily drinking salt water, we stumble upon Bali’s most enthralling hideaway and meet Bali’s savviest man, general manager Gusti at Plataran Menjangan (an eco-luxury resort in a destination unbothered about -

From the Jungles of Sumatra and the Beaches of Bali to the Surf Breaks of Lombok, Sumba and Sumbawa, Discover the Best of Indonesia

INDONESIAThe Insiders' Guide From the jungles of Sumatra and the beaches of Bali to the surf breaks of Lombok, Sumba and Sumbawa, discover the best of Indonesia. Welcome! Whether you’re searching for secluded surf breaks, mountainous terrain and rainforest hikes, or looking for a cultural surprise, you’ve come to the right place. Indonesia has more than 18,000 islands to discover, more than 250 religions (only six of which are recognised), thousands of adventure activities, as well as fantastic food. Skip the luxury, packaged tours and make your own way around Indonesia with our Insider’s tips. & Overview Contents MALAYSIA KALIMANTAN SULAWESI Kalimantan Sumatra & SUMATRA WEST PAPUA Jakarta Komodo JAVA Bali Lombok Flores EAST TIMOR West Papua West Contents Overview 2 West Papua 23 10 Unique Experiences A Nomad's Story 27 in Indonesia 3 Central Indonesia Where to Stay 5 Java and Central Indonesia 31 Getting Around 7 Java 32 & Java Indonesian Food 9 Bali 34 Cultural Etiquette 1 1 Nusa & Gili Islands 36 Sustainable Travel 13 Lombok 38 Safety and Scams 15 Sulawesi 40 Visa and Vaccinations 17 Flores and Komodo 42 Insurance Tips Sumatra and Kalimantan 18 Essential Insurance Tips 44 Sumatra 19 Our Contributors & Other Guides 47 Kalimantan 21 Need an Insurance Quote? 48 Cover image: Stocksy/Marko Milovanović Stocksy/Marko image: Cover 2 Take a jungle trek in 10 Unique Experiences Gunung Leuser National in Indonesia Park, Sumatra Go to page 20 iStock/rosieyoung27 iStock/South_agency & Overview Contents Kalimantan Sumatra & Hike to the top of Mt. -

MZB Profile English

Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense Zoology Division “Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense” Bogor Zoological Museum Research Center for Biology Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) Zoology Division “Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense” Research Center for Biology Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) 2018 The History Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense or Bogor Zoological Museum (MZB) was initiated in 1894 by Dr. J.C. Koningsberger. Started as Landbouw Zoologisch The museum started as a humble Laboratory located in Bogor Botanical Laboratorium, this early laboratory Garden called Landbouw Zoologisch Laboratorium. was responsible for conducting research and collection of crop- In 1898, Dr. J.C. Koningsberger related insects. and Dr. M. Treub visited the Colombo Museum in Ceylon (currently known as Sri Lanka). Admiration for the zoological collections at the Colombo Museum had inspired the development of Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense. 1 Dr. J.C. Koningsberger in the crater of Mount Gede, West Java, ca. 1915. Timeline Since its establishment, the museum 2001 - 2014 2014 - Present has been recognized with several Bidang Zoologi 11 12 Bidang Zoologi “Museum Zoologicum different affiliations and names. Bogoriense” 1962 - 1986 1987 - 2001 Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense 09 10 Balai Penelitian dan Today, the Museum is officially Pengembangan Zoologi known as Zoology Division 1947 - 1954 1955 - 1962 “Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense”, Research Center for Biology (RCB)- Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense 07 08 Lembaga Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI). 1942 - 1945 1946 - 1947 Dobutsu Hakubutsukan Zoologisch Museum en 05 06 Laboratorium 1906 - 1909 1910 - 1942 Zoologisch Museum 03 04 Zoologisch Museum en en Werkplaats Laboratorium 2 1894 1898 Landbouw Zoologisch 01 02 Landbouw Zoologisch Museum Laboratorium The Museum Logo The logo of MZB first appeared in the scientific journal Treubia Vol. -

Mapping a Policy-Making Process the Case of Komodo National Park, Indonesia

THESIS REPORT Mapping a Policy-making Process The case of Komodo National Park, Indonesia Novalga Aniswara MSc Tourism, Society & Environment Wageningen University and Research A Master’s thesis Mapping a policy-making process: the case of Komodo National Park, Indonesia Novalga Aniswara 941117015020 Thesis Code: GEO-80436 Supervisor: prof.dr. Edward H. Huijbens Examiner: dr. ir. Martijn Duineveld Wageningen University and Research Department of Environmental Science Cultural Geography Chair Group Master of Science in Tourism, Society and Environment i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Tourism has been an inseparable aspect of my life, starting with having a passion for travelling until I decided to take a big step to study about it back when I was in vocational high school. I would say, learning tourism was one of the best decisions I have ever made in my life considering opportunities and experiences which I encountered on the process. I could recall that four years ago, I was saying to myself that finishing bachelor would be my last academic-related goal in my life. However, today, I know that I was wrong. With the fact that the world and the industry are progressing and I raise my self-awareness that I know nothing, here I am today taking my words back and as I am heading towards the final chapter from one of the most exciting journeys in my life – pursuing a master degree in Wageningen, the Netherlands. Never say never. In completing this thesis, I received countless assistances and helps from people that I would like to mention. Firstly, I would not be at this point in my life without the blessing and prayers from my parents, grandma, and family. -

Hemi Kingi by Brian Sheppard 9 Workshop Reflections by Brian Sheppard 11

WORLD HERITAGE MANAGERS WORKSHOP PROCEEDINGS OF THE WORLD HERITAGE MANAGERS WORKSHOP Tongariro National Park, New Zealand 26–30 October 2000 Contents/Introduction 1 WORLD HERITAGE MANAGERS WORKSHOP Cover: Ngatoroirangi, a tohunga and navigator of the Arawa canoe, depicted rising from the crater to tower over the three sacred mountains of Tongariro National Park—Tongariro (foreground), Ngauruhoe, and Ruapehu (background). Photo montage: Department of Conservation, Turangi This report was prepared for publication by DOC Science Publishing, Science & Research Unit, Science Technology and Information Services, Department of Conservation, Wellington; design and layout by Ian Mackenzie. © Copyright October 2001, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISBN 0–478–22125–8 Published by: DOC Science Publishing, Science & Research Unit Science and Technical Centre Department of Conservation PO Box 10-420 Wellington, New Zealand Email: [email protected] Search our catalogue at http://www.doc.govt.nz 2 World Heritage Managers Workshop—Tongariro, 26–30 October 2000 WORLD HERITAGE MANAGERS WORKSHOP CONTENTS He Kupu Whakataki—Foreword by Tumu Te Heuheu 7 Hemi Kingi by Brian Sheppard 9 Workshop reflections by Brian Sheppard 11 EVALUATING WORLD HERITAGE MANAGEMENT 13 KEYNOTE SPEAKERS Performance management and evaluation 15 Terry Bailey, Projects Manager, Kakadu National Park, NT, Australia Managing our World Heritage 25 Hugh Logan, Director General, Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand Tracking the fate of New Zealand’s natural -

KOMODO DRAGON Varanus Komodoensis

KOMODO DRAGON Varanus komodoensis Location: The Komodo dragon (or ora) can be found in the lesser Sunda region of the Indonesian archipelago. This are includes the islands of Komodo, Flores, Rinca and Padar. Komodo is the largest of the islands, measuring roughly 20 miles by 12 miles. The Komodo dragon prefers to inhabit open lowland areas with tall grasses and bushes, but is also found on the beaches and in dry riverbeds. Young Komodo dragons are arboreal and live in forested regions. Diet: Carrion is a large part of the diet of adult Komodo dragons. It is common for them to attack and eat a variety of large prey, including goats, pigs, deer, wild boar, water buffalo and smaller Komodo dragons. Juveniles are more mobile than adults are, actively hunting and feeding on insects, small geckos, rats, shrews, and ground-nesting birds and their eggs. Komodo dragons ambush large prey and deliver a bite. They follow the injured animal until it succumbs to either blood loss or infection. The Komodo dragons’ saliva contains more than 50 different strains of bacteria that results in the death of prey from infection after being bitten. The Komodo dragon locates its prey by following a scent trail. Dragons frequently feed in groups; as many as 8 of them have been observed around a bulky carcass. The larger lizards monopolize the food, keeping younger individuals away by intimidating them or beating them off with sideways sweeps of their powerful tails. Once the bigger animals have finished eating, the smaller dragons are able to come in and feed. -

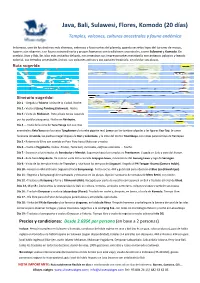

Java, Bali, Sulawesi, Flores, Komodo (20 Días)

Java, Bali, Sulawesi, Flores, Komodo (20 días) Templo s, volcanes, culturas ancestral es y fauna endémica Indonesia, uno de los destinos más diversos, extensos y fascinantes del planeta, guarda secretos lejos del turismo de masas, lugares aún vírgenes, con fauna extraordinaria y grupos humanos con tradiciones ancestrales, como Sulawesi y Komodo . En cambio, Java y Bali, la s islas más visitadas del país, nos muestran sus impresionantes metrópolis con antiguos palacios y legado colonial, sus templos ancestrales únicos, sus volcanes activos y sus paisajes tropicials, sin olvidar sus playas. Ruta sugerida Itinerario sugerido: Día 1 .- Llegada a Yakarta i visita de la ciudad. Noche. Día 2.- Vuelo a Ujung Pandang (Sulawesi). Noche. Dia 3.- Visita de Makassar. Ruta al pais toraja pasando por los pueblos pesqueros. Noche en Rantepao. Día 4 .-. Visita de la zona de Tana Toraja con sus ritos ancestrales: Kete'kesu con las casas Tongkonan y la tumba gigante real, Lemo con las tumbas colgadas y las figuras Tau-Tau , la cueva funeraria de Londa , las piedras megal.lítiques de Bori y Lokomata , y la cima del monte Tinombayo , con vistas panorámicas de Rantepao. Día 5.- Retorno de 8 hrs con comida en Pare-Par e hasta Makassar y noche.. Día 6 .- Vuelo a Yogjakarta . Visitas: Kraton, Tama Sari, mercados, edificios coloniales ... Noche. Día 7.- Excursión a los templos de Borobudur y Mendut. Seguimos hacia los templos de Prambanan . Llegada en Solo y vista de l Kraton . Día 8.- Ruta hacia Mojokerto . De camino visita de la cascada Grojogan Sewu , monasterios del Gunung Lawu y lago de Sarangan . -

Singapore U Bali U Borneo Java U Borobudur U Komodo

distinguished travel for more than 35 years u u Singapore Bali Borneo Java u Borobudur u Komodo INDONESIA THAILAND a voyage aboard the Bangkok CAMBODIA Kumai BORNEO Exclusively Chartered Siem Reap South Angkor Wat China Sea Five-Star Small Ship Tanjung Puting National Park Java Sea INDONESIA Le Lapérouse SINGAPORE Indian Semarang Ocean BALI MOYO JAVA ISLAND KOMODO Borobudur Badas Temple Prambanan Temple UNESCO World Heritage Site Denpasar Cruise Itinerary BALI Komodo SUMBAWA Air Routing National Park Land Routing September 23 to October 8, 2021 Singapore u Bali u Sumbawa u Semarang Kumai u Moyo Island u Komodo Island xperience the spectacular landscapes, tropical E 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada biodiversity and vast cultural treasures of Indonesia and 2 Cross the International Date Line Singapore on this comprehensive, 16-day journey 3 Arrive in Singapore featuring four nights in Five-Star hotels and an eight-night 4-5 Singapore/Fly to Bali, Indonesia 6 Denpasar, Bali cruise round trip Bali aboard the exclusively chartered, 7 Ubud/Benoa/Embark Le Lapérouse Five-Star Le Lapérouse. Discover Singapore’s compelling 8 Cruising the Java Sea to Java ethnic tableau, Bali’s authentic cultural traditions and 9 Semarang, Java (Borobudur and Prambanan Temples) 10 Cruising the Java Sea to Borneo breathtaking scenery, and the UNESCO-inscribed 11 Kumai, Borneo/Tanjung Puting National Park temples of Borobudur and Prambanan. Embark on a 12 Cruising the Java Sea to Sumbawa river cruise in Borneo to observe the world’s largest 13 Badas, Sumbawa/Moyo Island 14 Komodo Island (Komodo National Park) population of orangutans and visit Komodo Island 15 Denpasar, Bali/Disembark ship/Depart Bali/ to see its fabled dragons. -

Komodo National Park, Indonesia

Komodo National Park, Indonesia Trip Information ● Arrival airport: Komodo International Airport (LBJ) ● Departure airport: Komodo International Airport (LBJ) Flights and Transfers The liveaboard price includes transfers between the airport or local hotels and Indo Siren on the day of embarkation and on the day of disembarkation. Please refer to your booking and itinerary information for full details on transfers. Domestic flights to and from Labuan Bajo are not included. Advice on International Flights We suggest booking your international flights into Bali International Airport (DPS) for the easiest domestic connections to and from Labuan Bajo, although it is also possible to fly direct from Jakarta to Labuan Bajo. We advise you to spend at least one day in Jakarta or Bali at either side of your cruise to ensure you are on time for your flight connections and you are well rested before liveaboard departure. Our reservations team can help to arrange hotel accommodation and your domestic flight connections between your arrival airport and embarkation point. Please note that some domestic airlines have luggage restrictions of 10kg or 15kg with extra allowances only purchasable at the check in counter for approximately US$1.50 per kilo. However, Garuda Indonesia allows 20kg checked luggage on domestic flights, plus an additional free for sports equipment allowance of up to 23kg. Visa and Passports Passport holders of most Western countries can obtain a 30-day visa on arrival. As visa and passport regulations differ per country and are subject to change we advise guests to check for any updates or changes of visa procedures with their nearest embassy or consulate or the Indonesian Government's Directorate General of Immigration's website. -

For Creative Minds

For Creative Minds This section may be photocopied or printed from our website by the owner of this book for educational, non-commercial use. Cross-curricular teaching activities for use at home or in the classroom, interactive quizzes, and more are available online. Visit www.ArbordalePublishing.com to explore additional resources. Dragons by the Numbers 1 number of months a Komodo dragon 300 pounds (136 kg) a full-grown Komodo can go without food dragon weighs with a full belly I’m so stuffed I couldn’t eat I’m big, I’m bad, and I’m on the hunt. for a month! 1980 5 year Komodo National Park number of islands where Komodo was established dragons live in the wild Finally! Those humans were eating me It’s a little snug, but it’s home. out of house and home. 13 3,000 baby Komodo dragons hatched at the estimated number of Komodo National Zoo in 1992 dragons left in the world Well this isn’t my island . We’d better get hatching! 30 years in a Komodo dragon’s lifespan I’ll be an old dragon by the time you finish college! 95 degrees Fahrenheit (35 °C) in Komodo dragons’ natural habitat Ahh, nice and warm. Conservation Komodo dragons live in Indonesia, a Arctic Ocean country in Southeast Asia. These giant North Europe reptiles have been around for millions of America Asia Atlantic years. They are the largest living lizards Pacific in the world! Ocean Pacific Africa Ocean There are many threats to Komodo Ocean South Indian dragons. -

Southeast-Asia-On-A-Shoestring-17-Contents.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Southeast Asia on a shoestring Myanmar (Burma) p480 Laos p311 Thailand Vietnam p643 p812 Cambodia Philippines p64 p547 Brunei Darussalam p50 Malaysia p378 Singapore p613 Indonesia Timor- p149 Leste p791 THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY China Williams, Greg Bloom, Celeste Brash, Stuart Butler, Shawn Low, Simon Richmond, Daniel Robinson, Iain Stewart, Ryan Ver Berkmoes, Richard Waters PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to BRUNEI Batu .Karas. 169 Southeast Asia . .6 DARUSSALAM . 50 Wonosobo. 170 Southeast Asia Map . .8 Bandar Seri Begawan . 53 Dieng .Plateau. 170 Southeast Asia’s Top 20 . .10 Jerudong. 58 Yogyakarta. 171. Muara. 59 Prambanan. 179 Need to Know . 20 Temburong.District. 59 Borobudur. 179 First Time Understand Brunei Solo .(Surakarta). 182 Southeast Asia . 22 Darussalam . 60 Malang .&.Around. 185 If You Like… . 24 Survival Guide . 61 Gunung .Bromo. 187 Month by Month . 26 CAMBODIA . 64 Bondowoso. 190 Ijen .Plateau. 190 Itineraries . 30 Phnom Penh . 68 Banyuwangi. 191 Off the Beaten Track . 36 Siem Reap & the Temples of Angkor . 85 Bali . .191 Big Adventures, Siem .Reap. 86 Kuta, .Legian,.Seminyak.. Small Budget . 38 & .Kerabokan. 195 Templesf .o .Angkor. 94 Canggu .Area. .202 Countries at a Glance . 46 Northwestern Cambodia . 103 Bukit .Peninsula .. .. .. .. .. .. ...202 Battambang.. 103 Denpasar. .204 117 IMAGERY/GETTY IMAGES © Prasat .Preah.Vihear.. 108 Sanur. .206 Kompong .Thom.. 110 Nusa .Lembongan. 207 South Coast . 111 Ubud. .208 Koh .Kong.City.. .111 East .Coast.Beaches. 215 Koh .Kong.. Semarapura.(Klungkung). 215. Conservation.Corridor . 114 Sidemen .Road . 215 Sihanoukville.. 114 Padangbai. 215 The .Southern.Islands . 121 Candidasa. 216 Kampot.. 122 Tirta .Gangga. -

Wildlife-Animal Tourism Development and Lessons from Indonesia

69 C-02 WILDLIFE-ANIMAL TOURISM DEVELOPMENT AND LESSONS FROM INDONESIA Budi Guntoro1 1Faculty of Animal Science, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Jl. Fauna 3, Yogyakarta, Indonesia 55281 (E-mail: [email protected]) Introduction Wildlife-animal tourism encompasses a range of activities, including bird watching, wildlife viewing, photographic and walking safaris, reef diving, whale watching, trophy hunting and sport fishing. Wildlife tourism may be achieved through many different forms of transport, including on foot, by vehicle, boat or balloon. Wildlife tourism may be purposeful or may also include tourists who visit wildlife areas as an incidental part of a broader trip. Business trips may also involve visits to wildlife areas that are casual diversions rather than the prime motivation for visiting a country. Wildlife tourism is an important component of the international and domestic tourism industry. Overall, depending on the region, wildlife tourism accounts for 20 to 40 per cent of international tourism (Filion et al.1992; Giongo et al.1993, CEP 1994). The scale of wildlife tourism is even larger if domestic wildlife tourism is taken into consideration. However, statistics are often not available to determine what proportion of wildlife tourism is domestic in origin, but it is likely to be very high in some countries. As with tourism generally, wildlife tourism is likely to increase in importance and scale (Giongo et al. 1993). Furthermore, it may also attract an increasing market share, as suggested by a number of surveys indicating an increasing interest in wildlife among tourists. The last 20 years have seen a shift in favoured tourism destinations towards developing countries, especially those rich in biodiversity.