Coastal Communities Under Threat: Comparing Property and Social Exposure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONTENTS Page ORDINANCES CONFIRMED Confirmation of Ordinances Nos

NO. 1483 THURSDAY, 21ST MARCH, 1946 295 CONTENTS Page ORDINANCES CONFIRMED Confirmation of Ordinances Nos. 31, 40 and 42 of 1945 - - - 297 GOVERNMENT NOTICES Leave of Government Officers—Approval of - - - 297 Appointments, etc. ______ 297 ־ ־ ' ־ Inscription of Name on the Roll of Advocates - 298 List of Advocates who paid Annual Practising Fees - - - 298 Medical Licences cancelled _____ 298 Admission of Czech and Slovak Languages in Telegrams for Austria - - 298 Availability of a Restricted Telegraph Service to the whole of Siam - - 298 Acceptance of Telegrams to Malaya - - - - 298 ־ - Acceptance of Telegrams to B atavia, Netherland East Indies - 299 xi:eopening of Telephone Service with Great Britain - 299 ־ Opening of Restricted Postal Service with the Netherland East Indies - 299 ־•_ Availability of Parcel Post Service to China - - •_•299 ־ Palestine Post Office Savings Bank Deposit Book lost - - 299 Palestine Savings Certificate lost - - - - 299 Adjudication of Contract - - - - 299 Claims for Mutilated Currency Notes - - - - 300 ־ - - Citation Orders - - - 300 RETURNS ־ ־ ־ Persons changing their Names - 305 Financial Statement at 31st December, 1915 - - - - 306 Statement of Assets and Liabilities as at 31st December, 1945 - - - 308 Quarantine and Infectious Diseases Summary - 309 NOTICES REGARDING COOPERATIVE SOCIETIES, BANKRUPTCIES, ETC, - - - 309 CORRIGENDA - - - - - - - 312 SUPPLEMENT No. 2. The following .subsidiary legislation is published in Supplement No. 2 ichich forms part of this Gazette: — Order under the Immigration Ordinance, -

November 2001

m TELFED NOVEMBER i001 VOL. 27 NO. 3 A SOUTH AFRICAN ZIONIST FEDERATION (ISRAEL) PUBLICATION THE U.N. CONFERENCE ON R A C I S M I N D U R B A N D m \ m ( a ® M ^ M [ n r i f ^Dr.Ya'akov Kat/.. new face at the Minisuy of Education: Ariann Waliach, deer to ine: Impressions ofllie Durban NUPTIALS, ARRIVALS.... Bnoih Zioii CciUenar>'.... CoiiCcrencc AND MORE THE PRiNTINC AND DISTRIBUTION IN SOUTH AFRICA OF THIS ISSUE OF TELFED MAGAZINE IS SPONSORED BY THE IMMIGRATION AND ABSORPTION DEPARTMENT OF THE JEWISH AGENCY FOR ISRAEL. Because quality of life on a five-star level was always a prime consideration for us, we decided to turn it into a way of life This was the guideline that led us to Protea Village, where Itzak & Renate Unna everything is on a five-star level: tlie spacious homes, private gardens, 19 dunams of private park, central location in the heart of the Sharon, building standard, meticulous craftsmanship, Apartments for variety of activities, and most important of all, personal and immediate Occupation medical security for life. >^"'■"$159,000 To tell the truth, this is the only place where we found quality of life on a par with what we have seen throughout the world. B n e i D r o r J u n c t i o n Proteal^^Village * ' M R * h a n i n ^ u n c i i o n FIVE STAR RETIREMENT VILLAGE K , B o a D n r / t n r a c B - You're invited to join! 9 Ri&um Kft^Soba For further details, please phone: 1-800-374-888 or 09-796-7173 CONTENTS O F F T H E W A L L INTHEMAIL 1 in exasperation, wailing - we are all alone. -

Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict

Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict September 2000 - September 2007 L_C089061 Table of Contents: Foreword...........................................................................................................................1 Suicide Terrorists - Personal Characteristics................................................................2 Suicide Terrorists Over 7 Years of Conflict - Geographical Data...............................3 Suicide Attacks since the Beginning of the Conflict.....................................................5 L_C089062 Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict Foreword Since September 2000, the State of Israel has been in a violent and ongoing conflict with the Palestinians, in which the Palestinian side, including its various organizations, has carried out attacks against Israeli citizens and residents. During this period, over 27,000 attacks against Israeli citizens and residents have been recorded, and over 1000 Israeli citizens and residents have lost their lives in these attacks. Out of these, 155 (May 2007) attacks were suicide bombings, carried out against Israeli targets by 178 (August 2007) suicide terrorists (male and female). (It should be noted that from 1993 up to the beginning of the conflict in September 2000, 38 suicide bombings were carried out by 43 suicide terrorists). Despite the fact that suicide bombings constitute 0.6% of all attacks carried out against Israel since the beginning of the conflict, the number of fatalities in these attacks is around half of the total number of fatalities, making suicide bombings the most deadly attacks. From the beginning of the conflict up to August 2007, there have been 549 fatalities and 3717 casualties as a result of 155 suicide bombings. Over the years, suicide bombing terrorism has become the Palestinians’ leading weapon, while initially bearing an ideological nature in claiming legitimate opposition to the occupation. -

Ethiopian National Project Mid-Year Report 2016-2017

Ethiopian National Project Mid-Year Report 2016-2017 The Ethiopian National Project (ENP) was created by Jewish Federations as Diaspora Jewry’s tool to address the needs of Ethiopian-Israelis in partnership with the Government of Israel and the Ethiopian-Israeli community itself. The transformation ENP has succeeded in engendering is no less than extraordinary: scholastic gaps are closing, educational performance is improving, risk situations are decreasing and empowerment is broadening with each passing year. The Ethiopian National Project – Transformation of a Community ENP aims to ensure the full and successful integration of Ethiopian Jews into Israeli society. ENP’s methodology of holistic interventions on a national scale that fully include the Ethiopian-Israeli community, while strictly adhering to the critical importance of external evaluations to measure the impact and effect of ENP’s work, has resulted in unequivocally successful programs. In fact, due to its success, this school year brings new and exciting changes to ENP’s SPACE Scholastic Assistance Program, as part of a four-year initiative by the Government of Israel requesting that ENP expand its reach to 8,729 students in 35 cities nationwide while including 20% non- Ethiopian-Israeli students. In addition, where traditionally the Ministry of Aliyah and Absorption was the leading government ministry to spearhead ENP’s work, from 2016 the Ministry of Education will take the leading role as part of the new four-year initiative. In addition, the Jewish Federations of North America (JFNA) recently launched a campaign to raise matching dollars over four years to ensure that ENP can expand its SPACE Scholastic Assistance Program nationwide. -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Form 990 Under section 501 (c), 527, or 4947( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) 2005 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service ► The o rganization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state re porting requirements. A For the 2005 calendar year , or tax year be and B Check If C Name of organization D Employer Identification number applicable Please use IRS change ta Qachange RICA IS RAEL CULTURAL FOUNDATION 13-1664048 E; a11gne ^ci See Number and street (or P 0. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number 0jretum specific 1 EAST 42ND STREET 1400 212-557-1600 Instruo retum uons City or town , state or country, and ZIP + 4 F nocounwro memos 0 Cash [X ,camel ded On° EW YORK , NY 10017 (sped ► [l^PP°ca"on pending • Section 501 (Il)c 3 organizations and 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trusts H and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations. must attach a completed Schedule A ( Form 990 or 990-EZ). H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates ? Yes OX No G Website : : / /AICF . WEBNET . ORG/ H(b) If 'Yes ,* enter number of affiliates' N/A J Organization type (deckonIyone) ► [ 501(c) ( 3 ) I (insert no ) ] 4947(a)(1) or L] 527 H(c) Are all affiliates included ? N/A Yes E__1 No Is(ITthis , attach a list) K Check here Q the organization' s gross receipts are normally not The 110- if more than $25 ,000 . -

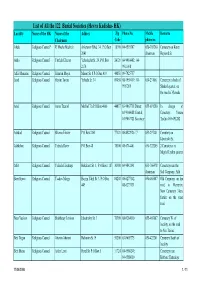

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No. Mobile Remarks Chairman Code phone no. Afula Religious Council* R' Moshe Mashiah Arlozorov Blvd. 34, P.O.Box 18100 04-6593507 050-303260 Cemetery on Keren 2041 chairman Hayesod St. Akko Religious Council Yitzhak Elharar Yehoshafat St. 29, P.O.Box 24121 04-9910402; 04- 2174 9911098 Alfei Menashe Religious Council Shim'on Moyal Manor St. 8 P.O.Box 419 44851 09-7925757 Arad Religious Council Hayim Tovim Yehuda St. 34 89058 08-9959419; 08- 050-231061 Cemetery in back of 9957269 Shaked quarter, on the road to Massada Ariel Religious Council Amos Tzuriel Mish'ol 7/a P.O.Box 4066 44837 03-9067718 Direct; 055-691280 In charge of 03-9366088 Central; Cemetery: Yoram 03-9067721 Secretary Tzefira 055-691282 Ashdod Religious Council Shlomo Eliezer P.O.Box 2161 77121 08-8522926 / 7 053-297401 Cemetery on Jabotinski St. Ashkelon Religious Council Yehuda Raviv P.O.Box 48 78100 08-6714401 050-322205 2 Cemeteries in Migdal Tzafon quarter Atlit Religious Council Yehuda Elmakays Hakalanit St. 1, P.O.Box 1187 30300 04-9842141 053-766478 Cemetery near the chairman Salt Company, Atlit Beer Sheva Religious Council Yaakov Margy Hayim Yahil St. 3, P.O.Box 84208 08-6277142, 050-465887 Old Cemetery on the 449 08-6273131 road to Harzerim; New Cemetery 3 km. further on the same road Beer Yaakov Religious Council Shabbetay Levison Jabotinsky St. 3 70300 08-9284010 055-465887 Cemetery W. -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

Palestine <5A3ette

Palestine <5a3ette Ipubltsbeb by Hutbodts No. 1031 THURSDAY, 18TH JULY, 1940 785 CONTENTS Page BILL PUBLISHED FOR INFORMATION ־ Extradition (Amendment) Bill, 1940 - 787- GOVERNMENT NOTICES ־ ־ - Acting Appointments - - 789 Applications for Appointments in the Irrigation Service - - - 789 Cancellation of Medical Licences ----- 789 Loss of a Midwife's Licence ----- 789 ־ Land Valuers' Licences granted - - - - 789 ־ - Intermediate Examination, 1940, of the Law Council - 789 Tender and Adjudication of Contracts - 789 ־ - Citation Orders - - - - 790 Notice to Claimants ------ 791 ־ ־ ־ ־ Court Notice - - > 791 Notices of the Execution Offices, Haifa and Tel Aviv - 791 RETURNS Quarantine and Infectious Diseases Summary - 794 Abstract of Receipts and Payments for the Year 1938/39 of the Municipal Corporation ־ - ־ ־ ־ of Gaza 795 Statement of Assets and Liabilities for the Year 1938/39 of the Municipal Corporation ־ of Gaza - - - - - 796 REGISTRATION OF PARTNERSHIPS, NOTICES, ETC. - - - - 797 ־ - - - - - - CORRIGENDA 800 SUPPLEMENT No. The following subsidiary legislation is published in Supplement No. 2 which forms part of this Gazette: — Defence (Amendment) Regulations (No. 4), 1940, under the Palestine (Defence) Order in 943־ - - - - - Council, 1937 Order under the Food and Essential Commodities (Control) Ordinance, 1939, prohibiting the Exportation of Wheat Flour, Butter or Sugar from the Municipal Areas of ־ ' - - - - - v Jaffa and Tel Aviv 943 {Continued) PBICB : 50 MILS. CONTENTS (Continued) Page Vesting Order No. 10 of 1940, under the -

The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem

Applied Research Institute - Jerusalem (ARIJ) P.O Box 860, Caritas Street – Bethlehem, Phone: (+972) 2 2741889, Fax: (+972) 2 2776966. [email protected] | http://www.arij.org Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Report on the Israeli Colonization Activities in the West Bank & the Gaza Strip Volume 188 , March 2014 Issue http://www.arij.org Bethlehem Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) stormed and toured in Ad-Doha and Beit Jala towns in Bethlehem governorate. (RB2000 1 March 2014) Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) stormed and searched a Palestinian house in Wadi Fukin village, west of Bethlehem city. (RB2000 1 March 2014) Israeli settlers attacked and injured Aref Aiesh Abidat and Iyoub Hssan Abidat while they were working in their land in Rummana area, east of Tequ village, southeast of Bethlehem city. (Maannews 1 March 2014) Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) handed out a military order to demolish a room in Wadi Rahal village, south of Bethlehem city. The targeted room is owned by Sami Issa Al-Fawaghira. (Maannews 1 March 2014) Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) opened fire and injured a Palestinian worker was identified as Amer Aiyed Abu Sarhan (36 years) from Al- Ubidiya town, east of Bethlehem city, while he was in Az-Za’em village, east of Jerusalem city. (Quds Net 2 March 2014) Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) invaded and searched the office of Palestinian Civil Defense in Al-Ubidiya town, east of Bethlehem city, and questioned the staff. (RB2000 2 March 2014) Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) erected military checkpoints at the entrances of Tequ village, southeast of Bethlehem city. The IOA stopped and searched Palestinian vehicles and checked ID cards. -

E ;Palestine ©Alette

e ;Palestine ©alette NO. 1658 THURSDAY, 1ST APRIL, 1948 247 CONTENTS Page GOVERNMENT NOTICES Appointment of Vice Consul of the United States of America at Jerusalem - 249 Appointment of Consul General of The Netherlands at Jerusalem - - 249 Appointment of Honorary Consul of Guatemala at Tel Aviv - - 249 ־ Appointment of Magistrate to act as Judge of the District Court - 249 Obituary - - - - - - 249 ־ * - - - - - Appointments, etc. 249 Loss of Palestine 3% Defence Bond Book - - - - 250 Statement of Currency Reserve- Fund - - - - 250 Tender - - - - - - 250 "The Fodder Resources of Palestine" on Sale - - - 250 Citation Orders - - ' - - - - 250 RETURNS Quarantine and Infectious Diseases Summary - 252 Summary of Receipts and Payments for the Year ended 31st March, 1947, of the Local Council of Kfar Yona - - - - - 253 Statement of Assets and Liabilities as at 31st March, 1947, of the Local Council of of Kfar Yona - - - - - - 254 Summary of Receipts and Payments for the Year ended 31st March, 1947, of the Local Council of Kiryat Motzkin - 255 Statement of Assets and Liabilities as at 31st March, 1947, of the Local Council of Kiryat Motzkin - - - - - - 256 Sale of Unclaimed Goods - - - - - 257 NOTICES REGARDING COOPERATIVE SOCIETIES, A BANKRUPTCY, ETC. - - 257 SUPPLEMENT No. 2. The following subsidiary legislation is published in Supplement No. 2 which forms part of this Gazette:— Double Taxation Relief (Taxes on Income) (United Kingdom) Order, 1948, under the Company Profits Tax Ordinance, 1947, and the Income Tax Ordinance, 1947 491 Law Council -

A Study of Ethiopian Jews Erich S

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Anthropology Department Honors Papers Anthropology Department 5-2009 Diasporic Identities in Israel: A Study of Ethiopian Jews Erich S. Roberts Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/anthrohp Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Roberts, Erich S., "Diasporic Identities in Israel: A Study of Ethiopian Jews" (2009). Anthropology Department Honors Papers. 2. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/anthrohp/2 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Department Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. Diasporic Identities in Israel: A Study of Ethiopian Jews by Erich S. Roberts Class of 2009 An honors thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology at Connecticut College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts Acknowledgements I would like to give thanks to all who have provided assistance in this past year. First and foremost, I would like to thank the Hiyot organization, especially its director, Nathalie, who gave me the opportunity to work with this community. And special thanks to the three employees of the youth club in Kiryat Motzkin for being patient with me; and to all of the teenagers, who flew in and out of the club, for taking me in as one of their own. -

List of Cities of Israel

Population Area SNo Common name District Mayor (2009) (km2) 1 Acre North 46,300 13.533 Shimon Lancry 2 Afula North 40,500 26.909 Avi Elkabetz 3 Arad South 23,400 93.140 Tali Ploskov Judea & Samaria 4 Ariel 17,600 14.677 Eliyahu Shaviro (West Bank) 5 Ashdod South 206,400 47.242 Yehiel Lasri 6 Ashkelon South 111,900 47.788 Benny Vaknin 7 Baqa-Jatt Haifa 34,300 16.392 Yitzhak Veled 8 Bat Yam Tel Aviv 130,000 8.167 Shlomo Lahiani 9 Beersheba South 197,300 52.903 Rubik Danilovich 10 Beit She'an North 16,900 7.330 Jacky Levi 11 Beit Shemesh Jerusalem 77,100 34.259 Moshe Abutbul Judea & Samaria 12 Beitar Illit 35,000 6.801 Meir Rubenstein (West Bank) 13 Bnei Brak Tel Aviv 154,400 7.088 Ya'akov Asher 14 Dimona South 32,400 29.877 Meir Cohen 15 Eilat South 47,400 84.789 Meir Yitzhak Halevi 16 El'ad Center 36,300 2.756 Yitzhak Idan 17 Giv'atayim Tel Aviv 53,000 3.246 Ran Kunik 18 Giv'at Shmuel Center 21,800 2.579 Yossi Brodny 19 Hadera Haifa 80,200 49.359 Haim Avitan 20 Haifa Haifa 265,600 63.666 Yona Yahav 21 Herzliya Tel Aviv 87,000 21.585 Yehonatan Yassur 22 Hod HaSharon Center 47,200 21.585 Hai Adiv 23 Holon Tel Aviv 184,700 18.927 Moti Sasson 24 Jerusalem Jerusalem 815,600 125.156 Nir Barkat 25 Karmiel North 44,100 19.188 Adi Eldar 26 Kafr Qasim Center 18,800 8.745 Sami Issa 27 Kfar Saba Center 83,600 14.169 Yehuda Ben-Hemo 28 Kiryat Ata Haifa 50,700 16.706 Ya'akov Peretz 29 Kiryat Bialik Haifa 37,300 8.178 Eli Dokursky 30 Kiryat Gat South 47,400 16.302 Aviram Dahari 31 Kiryat Malakhi South 20,600 4.632 Motti Malka 32 Kiryat Motzkin Haifa