A Study of Ethiopian Jews Erich S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Everyday Geopolitics of Messianic Jews in Israel-Palestine

Title Page The everyday geopolitics of Messianic Jews in Israel-Palestine. Daniel Webb Department of Geography, Royal Holloway, University of London. Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD, University of London, 2015. 1 Declaration I Daniel Webb hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Date: Sign: 2 Abstract This thesis examines the geopolitical orientations of Messianic Jews in Jerusalem, Israel-Palestine, in order to shed light on the confluence and co-constitution of religion and geopolitics. Messianic Jews are individuals who self-identify as being ethnically Jewish, but who hold beliefs that are largely indistinguishable from Christianity. Using the prism of ‘everyday geopolitics’, I explore my informants’ encounters with, and experiences of, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the dominant geopolitical logics that underpin it. I analyse the myriad of everyday factors that were formative in the shaping of my informants’ geopolitical orientation towards the conflict, focusing chiefly on those that were mediated and embodied through religious practice and belief. The material for the research was gathered in Jerusalem over the course of sixteen months – between September 2012 and January 2014 – largely through ethnographic research methods. Accordingly, I offer a lived alternative to existing work on geopolitics and religion; work that is dominated by overly cerebral and cognitivist views of religion. By contrast, I show how the urgencies of everyday life, as well as a number of religious practices, attune Messianic Jewish geopolitical orientations in dynamic, contingent, and contradictory ways. -

Print Friendly Version

TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 The Holiday of Hanukkah 5 Judaism and the Jewish Diaspora 8 Ashkenazi Jews and Yiddish 9 Latkes! 10 Pickles! 11 Body Mapping 12 Becoming the Light 13 The Nigun 14 Reflections with Playwright Shari Aronson 15 Interview with Author Eric Kimmel 17 Glossary 18 Bibliography Using the Guide Welcome, Teachers! This guide is intended as a supplement to the Scoundrel and Scamp’s production of Hershel & The Hanukkah Goblins. Please note that words bolded in the guide are vocabulary that are listed and defined at the end of the guide. 2 Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins Teachers Guide | The Scoundrel & Scamp Theatre The Holiday of Hanukkah Introduction to Hanukkah Questions: In Hebrew, the word Hanukkah means inauguration, dedication, 1. What comes to your mind first or consecration. It is a less important Jewish holiday than others, when you think about Hanukkah? but has become popular over the years because of its proximity to Christmas which has influenced some aspects of the holiday. 2. Have you ever participated in a Hanukkah tells the story of a military victory and the miracle that Hanukkah celebration? What do happened more than 2,000 years ago in the province of Judea, you remember the most about it? now known as Palestine. At that time, Jews were forced to give up the study of the Torah, their holy book, under the threat of death 3. It is traditional on Hanukkah to as their synagogues were taken over and destroyed. A group of eat cheese and foods fried in oil. fighters resisted and defeated this army, cleaned and took back Do you eat cheese or fried foods? their synagogue, and re-lit the menorah (a ceremonial lamp) with If so, what are your favorite kinds? oil that should have only lasted for one night but that lasted for eight nights instead. -

CONTENTS Page ORDINANCES CONFIRMED Confirmation of Ordinances Nos

NO. 1483 THURSDAY, 21ST MARCH, 1946 295 CONTENTS Page ORDINANCES CONFIRMED Confirmation of Ordinances Nos. 31, 40 and 42 of 1945 - - - 297 GOVERNMENT NOTICES Leave of Government Officers—Approval of - - - 297 Appointments, etc. ______ 297 ־ ־ ' ־ Inscription of Name on the Roll of Advocates - 298 List of Advocates who paid Annual Practising Fees - - - 298 Medical Licences cancelled _____ 298 Admission of Czech and Slovak Languages in Telegrams for Austria - - 298 Availability of a Restricted Telegraph Service to the whole of Siam - - 298 Acceptance of Telegrams to Malaya - - - - 298 ־ - Acceptance of Telegrams to B atavia, Netherland East Indies - 299 xi:eopening of Telephone Service with Great Britain - 299 ־ Opening of Restricted Postal Service with the Netherland East Indies - 299 ־•_ Availability of Parcel Post Service to China - - •_•299 ־ Palestine Post Office Savings Bank Deposit Book lost - - 299 Palestine Savings Certificate lost - - - - 299 Adjudication of Contract - - - - 299 Claims for Mutilated Currency Notes - - - - 300 ־ - - Citation Orders - - - 300 RETURNS ־ ־ ־ Persons changing their Names - 305 Financial Statement at 31st December, 1915 - - - - 306 Statement of Assets and Liabilities as at 31st December, 1945 - - - 308 Quarantine and Infectious Diseases Summary - 309 NOTICES REGARDING COOPERATIVE SOCIETIES, BANKRUPTCIES, ETC, - - - 309 CORRIGENDA - - - - - - - 312 SUPPLEMENT No. 2. The following .subsidiary legislation is published in Supplement No. 2 ichich forms part of this Gazette: — Order under the Immigration Ordinance, -

From Falashas to Ethiopian Jews

FROM FALASHAS TO ETHIOPIAN JEWS: THE EXTERNAL INFLUENCES FOR CHANGE C. 1860-1960 BY DANIEL P. SUMMERFIELD A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON (SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES) FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (PhD) 1997 ProQuest Number: 10673074 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673074 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT The arrival of a Protestant mission in Ethiopia during the 1850s marks a turning point in the history of the Falashas. Up until this point, they lived relatively isolated in the country, unaffected and unaware of the existence of world Jewry. Following this period and especially from the beginning of the twentieth century, the attention of certain Jewish individuals and organisations was drawn to the Falashas. This contact initiated a period of external interference which would ultimately transform the Falashas, an Ethiopian phenomenon, into Ethiopian Jews, whose culture, religion and identity became increasingly connected with that of world Jewry. It is the purpose of this thesis to examine the external influences that implemented and continued the process of transformation in Falasha society which culminated in their eventual emigration to Israel. -

November 2001

m TELFED NOVEMBER i001 VOL. 27 NO. 3 A SOUTH AFRICAN ZIONIST FEDERATION (ISRAEL) PUBLICATION THE U.N. CONFERENCE ON R A C I S M I N D U R B A N D m \ m ( a ® M ^ M [ n r i f ^Dr.Ya'akov Kat/.. new face at the Minisuy of Education: Ariann Waliach, deer to ine: Impressions ofllie Durban NUPTIALS, ARRIVALS.... Bnoih Zioii CciUenar>'.... CoiiCcrencc AND MORE THE PRiNTINC AND DISTRIBUTION IN SOUTH AFRICA OF THIS ISSUE OF TELFED MAGAZINE IS SPONSORED BY THE IMMIGRATION AND ABSORPTION DEPARTMENT OF THE JEWISH AGENCY FOR ISRAEL. Because quality of life on a five-star level was always a prime consideration for us, we decided to turn it into a way of life This was the guideline that led us to Protea Village, where Itzak & Renate Unna everything is on a five-star level: tlie spacious homes, private gardens, 19 dunams of private park, central location in the heart of the Sharon, building standard, meticulous craftsmanship, Apartments for variety of activities, and most important of all, personal and immediate Occupation medical security for life. >^"'■"$159,000 To tell the truth, this is the only place where we found quality of life on a par with what we have seen throughout the world. B n e i D r o r J u n c t i o n Proteal^^Village * ' M R * h a n i n ^ u n c i i o n FIVE STAR RETIREMENT VILLAGE K , B o a D n r / t n r a c B - You're invited to join! 9 Ri&um Kft^Soba For further details, please phone: 1-800-374-888 or 09-796-7173 CONTENTS O F F T H E W A L L INTHEMAIL 1 in exasperation, wailing - we are all alone. -

Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict

Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict September 2000 - September 2007 L_C089061 Table of Contents: Foreword...........................................................................................................................1 Suicide Terrorists - Personal Characteristics................................................................2 Suicide Terrorists Over 7 Years of Conflict - Geographical Data...............................3 Suicide Attacks since the Beginning of the Conflict.....................................................5 L_C089062 Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict Foreword Since September 2000, the State of Israel has been in a violent and ongoing conflict with the Palestinians, in which the Palestinian side, including its various organizations, has carried out attacks against Israeli citizens and residents. During this period, over 27,000 attacks against Israeli citizens and residents have been recorded, and over 1000 Israeli citizens and residents have lost their lives in these attacks. Out of these, 155 (May 2007) attacks were suicide bombings, carried out against Israeli targets by 178 (August 2007) suicide terrorists (male and female). (It should be noted that from 1993 up to the beginning of the conflict in September 2000, 38 suicide bombings were carried out by 43 suicide terrorists). Despite the fact that suicide bombings constitute 0.6% of all attacks carried out against Israel since the beginning of the conflict, the number of fatalities in these attacks is around half of the total number of fatalities, making suicide bombings the most deadly attacks. From the beginning of the conflict up to August 2007, there have been 549 fatalities and 3717 casualties as a result of 155 suicide bombings. Over the years, suicide bombing terrorism has become the Palestinians’ leading weapon, while initially bearing an ideological nature in claiming legitimate opposition to the occupation. -

Max-Planck-Institut Für Ethnologische Forschung Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology

Max-Planck-Institut für ethnologische Forschung Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology International Workshop INTEGRATION AND CONFLICT AMONG THE AFRICAN DIASPORA IN THE ORIENT November 8th – 9th 2007 Organiser: Ababu Minda Yimene Venue: Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Halle/S., Germany OUTLINE The Siddi are Indians of African origin, whose ancestors arrived in India beginning in the first century A.D. as sailors, domestic servants, serviles, soldiers, free adventurers and merchants. From the 13th to the 17th century India saw a large influx of Siddis as more African personnel were needed for the armies of the rising and expanding Moslem kingdoms of India. Not seldomly did Siddis rise to prominence, attaining military and governmental leadership positions. In fact, some established their own kingdoms, whose dynasties lasted even into the British rule of India. Two cases in point are the State of Habshan in Janjira and the State of Sachin. Siddis have adopted the indigenous religions (most Siddis are Muslim), food, and customs of India, though remnants of their African heritage are retained in their music. Since the Police Action of 1949-51, the armies of India’s princely states were dissolved and power was taken over by the Indian Union Army. The soldiers, including the Siddi, were retired with pensions, a drastic change for which they were ill-prepared. Moreover, as India vigorously strived to join the ranks of industrialised nations, the urban economy was subsequently transformed and the living standard of Siddis stagnated for lack of modern education and marketable skills. The identity of the Siddis has been changing since their arrival in India and especially so since India’s independence which led to the dissolution of the princely states. -

Ethiopian Jews in Canada: a Process of Constructing an Identity

Ethiopian Jews in Canada: A Process of Constructing an Identity Esther Grunau Department of Anthropology McGill University, Montreal c November, 1995 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts, Anthropology. © Esther Grunau, 1995 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ll Abstract IV Chapter 1 : Introduction 1 Chapter 2: Historical Background 17 Chapter 3: Emigration out ofEthiopia 32 Chapter 4: The Construction of Group Identity in Israel 46 Chapter 5: The Canadian Experience 70 Conclusion Ill Appendix A: Maps 113 Appendix B: Ethiopian Jewish Informants 115 Appendix C: Glossary 118 Appendix D: Abbreviations 120 References Cited 121 11 Acknowledgments This thesis could not have been completed without the support and assistance of several individuals and organizations. My supervisor, Professor Allan Young, encouraged me throughout the M.A. program and my thesis to push myself intellectually and creatively. I thank him for his gu~dance, constructive comments and support through my progression in the program and the evolution of my thesis. Professor Ell en Corin carefully supervised a readings course on Ethiopian Jews and identity which served as the background for this thesis. Throughout my progression in the course and in the M. A. program she was always available to discuss ideas with me, and her invaluable comments and support helped me to gain focus and direction in my work. Dr. Laurence Kirmayer provided me with a forum to explore the direction of my thesis through my involvement in the Culture and Mental Health Team. His insightful comments on how to link cultural anthropology with mental health challenged me to think more clearly about my graduate work and my career. -

Ethiopian National Project Mid-Year Report 2016-2017

Ethiopian National Project Mid-Year Report 2016-2017 The Ethiopian National Project (ENP) was created by Jewish Federations as Diaspora Jewry’s tool to address the needs of Ethiopian-Israelis in partnership with the Government of Israel and the Ethiopian-Israeli community itself. The transformation ENP has succeeded in engendering is no less than extraordinary: scholastic gaps are closing, educational performance is improving, risk situations are decreasing and empowerment is broadening with each passing year. The Ethiopian National Project – Transformation of a Community ENP aims to ensure the full and successful integration of Ethiopian Jews into Israeli society. ENP’s methodology of holistic interventions on a national scale that fully include the Ethiopian-Israeli community, while strictly adhering to the critical importance of external evaluations to measure the impact and effect of ENP’s work, has resulted in unequivocally successful programs. In fact, due to its success, this school year brings new and exciting changes to ENP’s SPACE Scholastic Assistance Program, as part of a four-year initiative by the Government of Israel requesting that ENP expand its reach to 8,729 students in 35 cities nationwide while including 20% non- Ethiopian-Israeli students. In addition, where traditionally the Ministry of Aliyah and Absorption was the leading government ministry to spearhead ENP’s work, from 2016 the Ministry of Education will take the leading role as part of the new four-year initiative. In addition, the Jewish Federations of North America (JFNA) recently launched a campaign to raise matching dollars over four years to ensure that ENP can expand its SPACE Scholastic Assistance Program nationwide. -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Form 990 Under section 501 (c), 527, or 4947( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) 2005 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service ► The o rganization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state re porting requirements. A For the 2005 calendar year , or tax year be and B Check If C Name of organization D Employer Identification number applicable Please use IRS change ta Qachange RICA IS RAEL CULTURAL FOUNDATION 13-1664048 E; a11gne ^ci See Number and street (or P 0. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number 0jretum specific 1 EAST 42ND STREET 1400 212-557-1600 Instruo retum uons City or town , state or country, and ZIP + 4 F nocounwro memos 0 Cash [X ,camel ded On° EW YORK , NY 10017 (sped ► [l^PP°ca"on pending • Section 501 (Il)c 3 organizations and 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trusts H and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations. must attach a completed Schedule A ( Form 990 or 990-EZ). H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates ? Yes OX No G Website : : / /AICF . WEBNET . ORG/ H(b) If 'Yes ,* enter number of affiliates' N/A J Organization type (deckonIyone) ► [ 501(c) ( 3 ) I (insert no ) ] 4947(a)(1) or L] 527 H(c) Are all affiliates included ? N/A Yes E__1 No Is(ITthis , attach a list) K Check here Q the organization' s gross receipts are normally not The 110- if more than $25 ,000 . -

A Bibliography on Christianity in Ethiopia Abbink, G.J

A bibliography on Christianity in Ethiopia Abbink, G.J. Citation Abbink, G. J. (2003). A bibliography on Christianity in Ethiopia. Asc Working Paper Series, (52). Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/375 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/375 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). African Studies Centre Leiden, the Netherlands ,, A Bibliography on Christianity in Eth J. Abbink ASC Working Paper 52/2003 Leiden: African Studies Centre 2003 © J. Abbink, Leiden 2003 Image on the front cover: Roof of the lih century rock-hewn church of Beta Giorgis in Lalibela, northern Ethiopia 11 Table of contents . Page Introduction 1 1. Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity and Missionary Churches: Historical, Political, Religious, and Socio-cultural Aspects 8 1.1 History 8 1.2 History of individual churches and monasteries 17 1.3 Aspects of doctrine and liturgy 18 1.4 Ethiopian Christian theology and philosophy 24 1.5 Monasteries and monastic life 27 1.6 Church, state and politics 29 1. 7 Pilgrimage 31 1.8 Religious and liturgical music 32 1.9 Social, cultural and educational aspects 33 1.10 Missions and missionary churches 37 1.11 Ecumenical relations 43 1.12 Christianity and indigenous (traditional) religions 44 1.13 Biographical studies 46 1.14 Ethiopian diaspora communities 47 2. Christian Texts, Manuscripts, Hagiographies 49 2.1 Sources, bibliographies, catalogues 49 2.2 General and comparative studies on Ethiopian religious literature 51 2.3 On saints 53 2.4 Hagiographies and related texts 55 2.5 Ethiopian editions and translations of the Bible 57 2.6 Editions and analyses of other religious texts 59 2.7 Ethiopian religious commentaries and exegeses 72 3. -

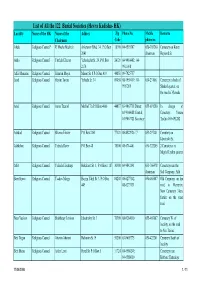

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No. Mobile Remarks Chairman Code phone no. Afula Religious Council* R' Moshe Mashiah Arlozorov Blvd. 34, P.O.Box 18100 04-6593507 050-303260 Cemetery on Keren 2041 chairman Hayesod St. Akko Religious Council Yitzhak Elharar Yehoshafat St. 29, P.O.Box 24121 04-9910402; 04- 2174 9911098 Alfei Menashe Religious Council Shim'on Moyal Manor St. 8 P.O.Box 419 44851 09-7925757 Arad Religious Council Hayim Tovim Yehuda St. 34 89058 08-9959419; 08- 050-231061 Cemetery in back of 9957269 Shaked quarter, on the road to Massada Ariel Religious Council Amos Tzuriel Mish'ol 7/a P.O.Box 4066 44837 03-9067718 Direct; 055-691280 In charge of 03-9366088 Central; Cemetery: Yoram 03-9067721 Secretary Tzefira 055-691282 Ashdod Religious Council Shlomo Eliezer P.O.Box 2161 77121 08-8522926 / 7 053-297401 Cemetery on Jabotinski St. Ashkelon Religious Council Yehuda Raviv P.O.Box 48 78100 08-6714401 050-322205 2 Cemeteries in Migdal Tzafon quarter Atlit Religious Council Yehuda Elmakays Hakalanit St. 1, P.O.Box 1187 30300 04-9842141 053-766478 Cemetery near the chairman Salt Company, Atlit Beer Sheva Religious Council Yaakov Margy Hayim Yahil St. 3, P.O.Box 84208 08-6277142, 050-465887 Old Cemetery on the 449 08-6273131 road to Harzerim; New Cemetery 3 km. further on the same road Beer Yaakov Religious Council Shabbetay Levison Jabotinsky St. 3 70300 08-9284010 055-465887 Cemetery W.