Pdf, 260.46 KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

People with Disabilities Get Ready: Curtis Mayfield in the 1990S Ray Pence, Ph.D

People with Disabilities Get Ready: Curtis Mayfield in the 1990s Ray Pence, Ph.D. University of Kansas Abstract: This article breaks with precedent by emphasizing disability’s role in the life and work of Curtis Mayfield (1942-1999) and by arguing that his experience of quadriplegia had both positive and difficult dimensions. Analysis focuses on Mayfield’s representation by journalists and other writers in the 1990s, and on how Mayfield answered their portrayals as an interview subject and as a musician with his final studio album New World Order (1996). Considered within the whole of Mayfield’s career, quadriplegia is revealed as one among many difficulties that he answered with critical positive thinking and powerful music. Key Words: quadriplegia, African-American music, civil rights “When a celebrity is ‘stricken’... editors and producers of national news organizations fall all over each other to run a mass-market variation on the theme, but in terms of narrative structure the celebrity story is simply the same notes scored for a symphony orchestra rather than a string quartet” (Riley, 2005, p. 13). Introduction Curtis Lee Mayfield (1942-1999) was a master of soul, rhythm, and blues with enormous and positive cultural influence in the last forty years of the twentieth century. Mayfield was also a person with disabilities—diabetes and, more significantly, quadriplegia—that he acquired late in life. Images are as important as sounds to understanding relationships between Mayfield’s quadriplegia and his music. Three contrasting views of Mayfield lying flat on his back during the 1990s provide a sort of visual synopsis of public perceptions of his final years. -

People Records Discography 5000 Series

People Records Discography 5000 series PLP 5001 - Big Brass Four Poster - KIM WESTON [1970] Big Brass Four Poster/Something I Can Feel/Love Don’t Let Me Down/He’s My Love/Here Come Those Heartaches Again/What’s Gonna Happen To Me//Something/My Man/Windmills Of Your Mind/Eleanor Rigby/Sound Of Silence PLP 5002 - Truth - TRUTH [1970] Have You Forgotten/Being Farmed/Anybody Here Know How To Pray/Wise Old Fool/Let It Out, Let It In/Far Out//Walk A Mile In My Shoes/Thoughts/New York/Contributin’/Lizzie/Talk 3000 series PS 3000 - The Grodeck Whipperjenny - The GRODECK WHIPPERJENNY [1971] Sitting Here On A Tongue/Wonder If/Why Can’t I Go Back/Conclusions/You’re Too Young//Put Your Thing On Me/Inside Or Outside/Evidence For The Existance Of The Unconscious 5600 series PE 5601 - Food For Thought - The J.B.’S [1972] Pass The Peas/Gimme Some More/To My Brother/Wine Spot/Hot Pants Road/The Grunt//Blessed Blackness/Escape-Ism (Part 1)/Escape-Ism (Part 2)/Theme From King Heroin/These Are The JB’s PE 5602 - Think (About It) - LYN COLLINS [1972] Think (About It)/Just Won’t Do Right/Wheels Of Life/Ain’t No Sunshine/Things Got To Get Better//Never Gonna Give You Up/Reach Out For Me/Women’s Lib/Fly Me To The Moon PE 5603 - Doing It To Death - FRED WESLEY & The J.B.’S [1973] Introduction To The J.B.’s/Doing It To Death (Part 1 & 2)/You Can Have Watergate Just Gimme Some Bucks And I’ll Be Straight/More Peas//La Di Da La Di Day/You Can Have Watergate Just Gimme Some Bucks And I’ll Be Straight/Sucker/You Can Have Watergate Just Gimme Some Bucks And I’ll Be Straight -

Southern Music and the Seamier Side of the Rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1995 The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Folklore Commons, Music Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hutson, Cecil Kirk, "The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South " (1995). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 10912. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/10912 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthiough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproductioiL In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Women's Resource Centre Fights 'For Survival • by Gall DOTINGA • Move Which' Wlliinerease Their Fund Raising Eal~Bllltlee

.............. =_--..='" - - ............. ~:} . , • LEGZSLAT£V¢- LZ~R~.R¥. CO! • ??/78 - ':•. -.. !-i ~ : !,~ "" . ;.:.:~ ,.; ~,~'. F~RL;,[~M~N'£ BU[LDIt~G~ ~ ' ..... ' ' : ' ,., '.... d westtour, st attraCtionclosedb: ¢o '" ~f''~" "' i~'~" :" ~' " J ~' : ~"" """ " " 'i'''M ' q ' "" ~"' ~ "' f J' " B r " I ~ ''id ~vo:lawmen- onearmed':I ,ry:::~na,.~s~".~m,~tY I from fed~l" "...~..~o.~Ued LI~ the,~e~l~",S~¢k _H~.,.o . ~:'No.,,l,0'.'embth "1 .b~.nedon~eftouta,~d.~e., " • :..DEADWOOD,....... S,D. (UPI) ~Theguys atth e , Wi~ " " " " ' " ' " " : " " "J ' .... ' ..... we~ filed ...... ue telchurch ! 'groups reee~Uy started a dead~d'= mane hand.:-- the ac~oyer-e . : ... ..... " ' , " ' • • s kin i aeled ehommer--ranupthestepsofone .prosecutlon ,No charges, against . v# .. .... .,..... ~.~.t aft. N 0. 1o,salonn were glum, Nothing so hoc g. w th g.'.. .... -:....._.,,.,... .....:-. ,. .... :.. ........ , houseHick0kheldwhenhewasshot .... .~. - . had Imnnan~d in nendwnad s|n~e Jack McCall of the town's tour..known brothels Wednesday,... th=,.... - .-. ._..... ..... .... ..._...ddve to have .tl~:.:,~.~ clmmd . ~ ,;~,,,,a.,,, ,,,,~ hJ~,~ • . .... ' " ' . bad.happenedinDeadw0edsinceJackMcCall, ofthetoW~ ..... ~nbmthel _ _ ty, ...... ....... -a_,_-_...msod_rev_iled. :....... -::! . --~ted,on th#back. "neddownWild Bill Hickok during a poker. arrested about .a. nozenwomen ann usnerou :..-..w.~nesoay mgn~,. '~,,y p ~u.¢, " '~rh,i li~.,~- I,-,,,, ,~.,..... ~,,,,~ * b ,~,d/ Ann~lly a "Dave of '76" rally drains • . ...,gtm.me at .....the No 10 . ' ,. • them into• a.waitmg-....... van, • ..., - -..- . atthe l~storlc• .- bar~ Of' the No. 10,where H(ckox s" ......... _ _ : _, . ,o,,,: =,,,oa,,.,,=uv,,---., .,-..; .. ....~ . ,- and• n attend With., ' . , '. ~,ga : ' , , - :. ." ' ' . • ...... ........ ." ................. .~ business because ot the towns locatlm..-In thou~u~ds of v~Itors ma y ..... .., : : That.was ~ Jtdy, of '76-- 1876,tSat is.--tbe..: :i,~..;: i,- .':: ~ -:" ;~ - ~;-:., ; .... .___..:_' Z"./.-e .,h~,r,.~.h~.g.,s.0_ve.~,~,~e.,d__onr_'_L,. -

The High School Student Drug Abuse Council, Inc., Washington, DC 293P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 110 868 CG 009 292 TITLE Students Speak on Drugs; The High School Student Project. INSTITUTION Drug Abuse Council, Inc., Washington, D.C. REPORT NO H S -3 PUB DATE Jun 74 NOTE 293p.; Some pages in the individual reportsmay reproduce poorly AVAILABLE FROM The Drug Abuse Council, Inc., 1828 L Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 (HC $2.25, $1.50 in quantities of 10 or more) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Drug Abuse; *Drug Education; Field Interviews; High School Students; *Program Evaluation; *Student Attitudes; *Student Research; Surveys ABSTRACT This report represents the findings obtained from investigations conducted by nine student researchgroups based in high school s in each geographical region of the UnitedStates. Each research group conducted three-month studies of the drug education programs and formulated recommendations for program modifications and new approaches. Major issues for fact finding included:(1) the incidence of drug abuse among high school students; (2) student attitudes on drug use and abuse;(3) the nature of existing drug education programs; (4) the effectiveness of those programs; and (5) students' perceptions of their drug education needs. The groups' research findings indicate widespread usage and availability of illicit drugs, failure of existing drug educationprograms to affect student drug usage, and the need for involvement of the community-at-large. The students repeatedly criticized the prevalence of a subject-matter orientation to school drugprograms, instead suggesting the need for a personal-problemsor social-problems orientation. Included in the report isa discussion of the limitations and weaknesses of this student project. -

Title Format Released Abyssinians, the Satta Dub CD 1998 Acklin

Title Format Released Abyssinians, The Satta Dub CD 1998 Acklin, Barbara The Brunswick Anthology (Disc 2) CD 2002 The Brunswick Anthology (Disc 1) CD 2002 Adams Johnny Johnny Adams Sings Doc Pomus: The Real Me CD 1991 Adams, Johnny I Won't Cry CD 1991 Walking On A Tightrope - The Songs Of Percy Mayfield CD 1989 Good Morning Heartache CD 1993 Ade & His African Beats, King Sunny Juju Music CD 1982 Ade, King Sunny Odu CD 1998 Alabama Feels So Right CD 1981 Alexander, Arthur Lonely Just Like Me CD 1993 Allison, DeAnn Tumbleweed CD 2000 Allman Brothers Band, The Beginnings CD 1971 American Song-poem Anthology, The Do You Know The Difference Between Big Wood And Brush CD 2003 Animals, The Animals - Greatest Hits CD 1983 The E.P. Collection CD 1964 Aorta Aorta CD 1968 Astronauts, The Down The Line/ Travelin' Man CD 1997 Competition Coupe/Astronauts Orbit Kampus CD 1997 Rarities CD 1991 Go Go Go /For You From Us CD 1997 Surfin' With The Astronauts/Everything Is A-OK! CD 1997 Austin Lounge Lizards Paint Me on Velvet CD 1993 Average White Band Face To Face - Live CD 1997 Page 1 of 45 Title Format Released Badalamenti, Angelo Blue Velvet CD 1986 Twin Peaks - Fire Walk With Me CD 1992 Badfinger Day After Day [Live] CD 1990 The Very Best Of Badfinger CD 2000 Baker, Lavern Sings Bessie Smith CD 1988 Ball, Angela Strehli & Lou Ann Barton, Marcia Dreams Come True CD 1990 Ballard, Hank Sexy Ways: The Best of Hank Ballard & The Midnighters CD 1993 Band, The The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down: The Best Of The Band [Live] CD 1992 Rock Of Ages [Disc 1] CD 1990 Music From Big Pink CD 1968 The Band CD 1969 The Last Waltz [Disc 2] CD 1978 The Last Waltz [Disc 1] CD 1978 Rock Of Ages [Disc 2] CD 1990 Barker, Danny Save The Bones CD 1988 Barton, Lou Ann Read My Lips CD 1989 Baugh, Phil 64/65 Live Wire! CD 1965 Beach Boys, The Today! / Summer Days (And Summer Nights!!) CD 1990 Concert/Live In London [Bonus Track] [Live] CD 1990 Pet Sounds [Bonus Tracks] CD 1990 Merry Christmas From The Beach Boys CD 2000 Beatles, The Past Masters, Vol. -

“We Wanted Our Coffee Black”: Public Enemy, Improvisation, and Noise

Critical Studies in Improvisation / Études critiques en improvisation, Vol 10, No 1 (2014) “We Wanted Our Coffee Black”: Public Enemy, Improvisation, and Noise Niel Scobie Introduction Outside of academic circles, “noise” often has pejorative connotations in the context of music, but what if it was a preferred aesthetic with respect to music making? In addition, what if the preferred noise aesthetic was a direct result of group improvisation? Caleb Kelly claims that “Subjective noise is the most common understanding of what noise is. Put simply, it is the sound of the complaint from a stereotypical mother screaming to her teenage son to ‘turn that noise off. To the parent, the aggravating noise is the sound of the music, while it is his mother’s’ voice that is noise to the teenager enjoying his music” (72-73). In Music and Discourse, Jean-Jacques Nattiez goes further to state that noise is not only subjective, its definition, and that of music itself, is culturally specific: “There is never a singular, culturally dominant conception of music; rather, we see a whole spectrum of conceptions, from those of the entire society to those of a single individual” (43). Nattiez quotes from René Chocholle’s Le Bruit to define “noise” as “any sound that we consider as having a disagreeable affective character”—making “the notion of noise [. .] first and foremost a subjective notion” (45). Noise in this context is, therefore, most often positioned as the result of instrumental or lyrical/vocal sounds that run contrary to an established set of musical -

Madonna - 1982 - 2009 : the Lyrics Book - 1 SOMMAIRE

Madonna - 1982 - 2009 : The Lyrics Book - www.madonnalex.net 1 SOMMAIRE P.03 P.21 P.51 P.06 P.26 P.56 P.09 P.28 P.59 P.10 P.35 P.66 P.14 P.40 P.74 P.15 P.42 P.17 P.47 Madonna - 1982 - 2009 : The Lyrics Book - www.madonnalex.net 2 ‘Cause you got the best of me Chorus: Borderline feels like I’m going to lose my mind You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline (repeat chorus again) Keep on pushing me baby Don’t you know you drive me crazy You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline Something in your eyes is makin’ such a fool of me When you hold me in your arms you love me till I just can’t see But then you let me down, when I look around, baby you just can’t be found Stop driving me away, I just wanna stay, There’s something I just got to say Just try to understand, I’ve given all I can, ‘Cause you got the best of me (chorus) Keep on pushing me baby MADONNA / Don’t you know you drive me crazy You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline THE FIRST ALBUM Look what your love has done to me 1982 Come on baby set me free You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline You cause me so much pain, I think I’m going insane What does it take to make you see? LUCKY STAR You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline written by Madonna 5:38 You must be my Lucky Star ‘Cause you shine on me wherever you are I just think of you and I start to glow BURNING UP And I need your light written by Madonna 3:45 Don’t put me off ‘cause I’m on fire And baby you know And I can’t quench my desire Don’t you know that I’m burning -

The Sounds of Liberation: Resistance, Cultural Retention, and Progressive Traditions for Social Justice in African American Music

THE SOUNDS OF LIBERATION: RESISTANCE, CULTURAL RETENTION, AND PROGRESSIVE TRADITIONS FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE IN AFRICAN AMERICAN MUSIC A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Professional Studies by Luqman Muhammad Abdullah May 2009 © 2009 Luqman Muhammad Abdullah ABSTRACT The cultural production of music in the Black community has traditionally operated as much more than a source of entertainment. In fact, my thesis illustrates how progressive traditions for social justice in Black music have acted as a source of agency and a tool for resistance against oppression. This study also explains how the music of African Americans has served as a primary mechanism for disseminating their cultural legacy. I have selected four Black artists who exhibit the aforementioned principles in their musical production. Bernice Johnson Reagon, John Coltrane, Curtis Mayfield and Gil Scott-Heron comprise the talented cadre of musicians that exemplify the progressive Black musical tradition for social justice in their respective genres of gospel, jazz, soul and spoken word. The methods utilized for my study include a socio-historical account of the origins of Black music, an overview of the artists’ careers, and a lyrical analysis of selected songs created by each of the artists. This study will contribute to the body of literature surrounding the progressive roles, functions and utilities of African American music. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH My mother garners the nickname “gypsy” from her siblings due to the fact that she is always moving and relocating to new and different places. -

2017MM@M Study Guide

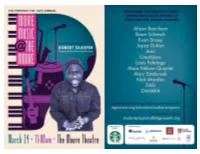

About Us Produced by STG’s Education and Community Programs, More Music @ The Moore (MM@M) is a young artist development program that provides talented young artists (ages 14-21) with the tools and setting to rehearse and perform music under the direction of industry mentors and professionals. The program culminates with two performances at The Moore Theatre, an 11am student matinee and 7:30pm public performance (March 24, 2017). STG is thrilled to welcome Robert Glasper as the Music Director of the 16th annual MM@M. A dynamic producer, composer, and pianist Robert Glasper has won 3 Grammy Awards of his own and contributed to a number of other award winning albums. What sets MM@M apart from other young artist performances is a focus on original work and cross-cultural collaboration. This year, over 150 musicians auditioned to be part of the program, the standard was higher than ever. The 14 selected musicians have come together for 2 months of outside rehearsal before a week of rehearsals at the Moore Theatre to create an innovative, collaborative performance under the artistic direction of Robert Glasper. MM@M is one of a number of STG programs that invests in the next generation of artists in Seattle. STG MISSION: Making performances and arts education in the Pacific Northwest enriching, while keeping Seattle’s historic Paramount, Moore and Neptune Theatres healthy and vibrant. ABOUT EDUCATION: Seattle Theatre Group Education and Community Programs extend beyond The Paramount, Moore and the Neptune Theatre stages and into the lives of the greater Seattle community. STG offered over 1000 programs last seasons impacting 41,695 students and community members from diverse ages and backgrounds. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Beil & Howell Information Company 300 Nortfi Z eeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 -1 3 4 6 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9218977 Shirley Caesar: A woman of words Harrington, Brooksie Eugene, Ph D. The Ohio State University, 1992 UMI 300 N. -

The Politics of Soul Music

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2005 Soul shakedown: The politics of soul music Melanie Catherine Young University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Young, Melanie Catherine, "Soul shakedown: The politics of soul music" (2005). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1917. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/9hmc-nb38 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOUL SHAKEDOWN: THE POLITICS OF SOUL MUSIC by Melanie Catherine Young Bachelor of Arts University of Nevada, Las Vegas 1 9 9 9 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Political Science Department of Political Science College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1435648 Copyright 2006 by Young, Melanie Catherine All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.