Dr. King's Struggle Then And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radio Essentials 2012

Artist Song Series Issue Track 44 When Your Heart Stops BeatingHitz Radio Issue 81 14 112 Dance With Me Hitz Radio Issue 19 12 112 Peaches & Cream Hitz Radio Issue 13 11 311 Don't Tread On Me Hitz Radio Issue 64 8 311 Love Song Hitz Radio Issue 48 5 - Happy Birthday To You Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 21 - Wedding Processional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 22 - Wedding Recessional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 23 10 Years Beautiful Hitz Radio Issue 99 6 10 Years Burnout Modern Rock RadioJul-18 10 10 Years Wasteland Hitz Radio Issue 68 4 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night Radio Essential IssueSeries 44 Disc 44 4 1975, The Chocolate Modern Rock RadioDec-13 12 1975, The Girls Mainstream RadioNov-14 8 1975, The Give Yourself A Try Modern Rock RadioSep-18 20 1975, The Love It If We Made It Modern Rock RadioJan-19 16 1975, The Love Me Modern Rock RadioJan-16 10 1975, The Sex Modern Rock RadioMar-14 18 1975, The Somebody Else Modern Rock RadioOct-16 21 1975, The The City Modern Rock RadioFeb-14 12 1975, The The Sound Modern Rock RadioJun-16 10 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 4 2 Pistols She Got It Hitz Radio Issue 96 16 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This Radio Essential IssueSeries 23 Disc 23 3 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 16 21 Savage Feat. J. Cole a lot Mainstream RadioMay-19 11 3 Deep Can't Get Over You Hitz Radio Issue 16 6 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Hitz Radio Issue 46 6 3 Doors Down Be Like That Hitz Radio Issue 16 2 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Hitz Radio Issue 62 16 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Hitz Radio Issue 12 15 3 Doors Down Here Without You Hitz Radio Issue 41 14 3 Doors Down In The Dark Modern Rock RadioMar-16 10 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time Hitz Radio Issue 95 3 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Hitz Radio Issue 3 9 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Hitz Radio Issue 57 15 3 Doors Down One Light Modern Rock RadioJan-13 6 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone Hitz Radio Issue 31 2 3 Doors Down Feat. -

People with Disabilities Get Ready: Curtis Mayfield in the 1990S Ray Pence, Ph.D

People with Disabilities Get Ready: Curtis Mayfield in the 1990s Ray Pence, Ph.D. University of Kansas Abstract: This article breaks with precedent by emphasizing disability’s role in the life and work of Curtis Mayfield (1942-1999) and by arguing that his experience of quadriplegia had both positive and difficult dimensions. Analysis focuses on Mayfield’s representation by journalists and other writers in the 1990s, and on how Mayfield answered their portrayals as an interview subject and as a musician with his final studio album New World Order (1996). Considered within the whole of Mayfield’s career, quadriplegia is revealed as one among many difficulties that he answered with critical positive thinking and powerful music. Key Words: quadriplegia, African-American music, civil rights “When a celebrity is ‘stricken’... editors and producers of national news organizations fall all over each other to run a mass-market variation on the theme, but in terms of narrative structure the celebrity story is simply the same notes scored for a symphony orchestra rather than a string quartet” (Riley, 2005, p. 13). Introduction Curtis Lee Mayfield (1942-1999) was a master of soul, rhythm, and blues with enormous and positive cultural influence in the last forty years of the twentieth century. Mayfield was also a person with disabilities—diabetes and, more significantly, quadriplegia—that he acquired late in life. Images are as important as sounds to understanding relationships between Mayfield’s quadriplegia and his music. Three contrasting views of Mayfield lying flat on his back during the 1990s provide a sort of visual synopsis of public perceptions of his final years. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Lupe Fiasco Discography Torrent

Lupe fiasco discography torrent Continue Lupe Piasco - Food and Liquor of Lupe Piasco (2006) 1. Intro 2. Real (Feat. Sarah Green) 3. It might just be fine (Feat. Gemini) 4. Kick, Push 5. I'm a high-order 6. Instrumental (feat Jonah Matraranga) 7. He says she (Feat Gemini and Sarah Green) 8. Sunshine 9. Daydreaming ' (Feat Jill Scott) 10. Cool 11. Wounds or souls 12. Pressure (Feat. J-Z) 13. American Terrorist (Feat Matthew Santos) 14. Emperor's Soundtrack 15. Kick, Push II 16. Outro Lupe Fiasco – Chi Town Guevara Mixtape (2006) 01 Intro 02 Touch Sky 03 Pressure 04 Kick Push 05 Failed 05 Failed 06 Twilight Zone 07 Average and Vicious 08 Just Ok Ft. Gemini 09 Switch 10 Dead Prez 11 Outty 5000 12 Pence and Needles 13 Lupe Gorilla 14 Lupe Killa 15 Jedi Mind Trick 16 Hurt or Soul 17 Kick Push Remix Ft. Skateboard P Lupe Piasco - Fahrenheit 1/15 (Part I - Truth Of Us 106) 106) Intro 2. Twilight Zone 3. Penn and Needles 4. Knockinin' Champ here (freestyle) 6 at Door 5. Failure 7. Bose Playa (Feat. Gemini and Bishop G) 8. Jesus Walk (Arc-A-Pella version) 9. WGCI (Freestyle) 10. Hate Hop 11. Run down 12. Oh 13. 14. Coffin' where I came from (feat Anthony Hamilton) 15. Sheila G Up (Feat. Sheila G) 16. Radio 17. Welcome back to chilly rupee piasco - Fahrenheit 1/15 (Part II - Nerd Revenge) (2006) 1. Revenge begins... 2. Much more 3. Average and vicious 4. Didn't you know? (Feat. Sheila G) 5. -

Title Format Released Abyssinians, the Satta Dub CD 1998 Acklin

Title Format Released Abyssinians, The Satta Dub CD 1998 Acklin, Barbara The Brunswick Anthology (Disc 2) CD 2002 The Brunswick Anthology (Disc 1) CD 2002 Adams Johnny Johnny Adams Sings Doc Pomus: The Real Me CD 1991 Adams, Johnny I Won't Cry CD 1991 Walking On A Tightrope - The Songs Of Percy Mayfield CD 1989 Good Morning Heartache CD 1993 Ade & His African Beats, King Sunny Juju Music CD 1982 Ade, King Sunny Odu CD 1998 Alabama Feels So Right CD 1981 Alexander, Arthur Lonely Just Like Me CD 1993 Allison, DeAnn Tumbleweed CD 2000 Allman Brothers Band, The Beginnings CD 1971 American Song-poem Anthology, The Do You Know The Difference Between Big Wood And Brush CD 2003 Animals, The Animals - Greatest Hits CD 1983 The E.P. Collection CD 1964 Aorta Aorta CD 1968 Astronauts, The Down The Line/ Travelin' Man CD 1997 Competition Coupe/Astronauts Orbit Kampus CD 1997 Rarities CD 1991 Go Go Go /For You From Us CD 1997 Surfin' With The Astronauts/Everything Is A-OK! CD 1997 Austin Lounge Lizards Paint Me on Velvet CD 1993 Average White Band Face To Face - Live CD 1997 Page 1 of 45 Title Format Released Badalamenti, Angelo Blue Velvet CD 1986 Twin Peaks - Fire Walk With Me CD 1992 Badfinger Day After Day [Live] CD 1990 The Very Best Of Badfinger CD 2000 Baker, Lavern Sings Bessie Smith CD 1988 Ball, Angela Strehli & Lou Ann Barton, Marcia Dreams Come True CD 1990 Ballard, Hank Sexy Ways: The Best of Hank Ballard & The Midnighters CD 1993 Band, The The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down: The Best Of The Band [Live] CD 1992 Rock Of Ages [Disc 1] CD 1990 Music From Big Pink CD 1968 The Band CD 1969 The Last Waltz [Disc 2] CD 1978 The Last Waltz [Disc 1] CD 1978 Rock Of Ages [Disc 2] CD 1990 Barker, Danny Save The Bones CD 1988 Barton, Lou Ann Read My Lips CD 1989 Baugh, Phil 64/65 Live Wire! CD 1965 Beach Boys, The Today! / Summer Days (And Summer Nights!!) CD 1990 Concert/Live In London [Bonus Track] [Live] CD 1990 Pet Sounds [Bonus Tracks] CD 1990 Merry Christmas From The Beach Boys CD 2000 Beatles, The Past Masters, Vol. -

Madonna - 1982 - 2009 : the Lyrics Book - 1 SOMMAIRE

Madonna - 1982 - 2009 : The Lyrics Book - www.madonnalex.net 1 SOMMAIRE P.03 P.21 P.51 P.06 P.26 P.56 P.09 P.28 P.59 P.10 P.35 P.66 P.14 P.40 P.74 P.15 P.42 P.17 P.47 Madonna - 1982 - 2009 : The Lyrics Book - www.madonnalex.net 2 ‘Cause you got the best of me Chorus: Borderline feels like I’m going to lose my mind You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline (repeat chorus again) Keep on pushing me baby Don’t you know you drive me crazy You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline Something in your eyes is makin’ such a fool of me When you hold me in your arms you love me till I just can’t see But then you let me down, when I look around, baby you just can’t be found Stop driving me away, I just wanna stay, There’s something I just got to say Just try to understand, I’ve given all I can, ‘Cause you got the best of me (chorus) Keep on pushing me baby MADONNA / Don’t you know you drive me crazy You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline THE FIRST ALBUM Look what your love has done to me 1982 Come on baby set me free You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline You cause me so much pain, I think I’m going insane What does it take to make you see? LUCKY STAR You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline written by Madonna 5:38 You must be my Lucky Star ‘Cause you shine on me wherever you are I just think of you and I start to glow BURNING UP And I need your light written by Madonna 3:45 Don’t put me off ‘cause I’m on fire And baby you know And I can’t quench my desire Don’t you know that I’m burning -

The Sounds of Liberation: Resistance, Cultural Retention, and Progressive Traditions for Social Justice in African American Music

THE SOUNDS OF LIBERATION: RESISTANCE, CULTURAL RETENTION, AND PROGRESSIVE TRADITIONS FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE IN AFRICAN AMERICAN MUSIC A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Professional Studies by Luqman Muhammad Abdullah May 2009 © 2009 Luqman Muhammad Abdullah ABSTRACT The cultural production of music in the Black community has traditionally operated as much more than a source of entertainment. In fact, my thesis illustrates how progressive traditions for social justice in Black music have acted as a source of agency and a tool for resistance against oppression. This study also explains how the music of African Americans has served as a primary mechanism for disseminating their cultural legacy. I have selected four Black artists who exhibit the aforementioned principles in their musical production. Bernice Johnson Reagon, John Coltrane, Curtis Mayfield and Gil Scott-Heron comprise the talented cadre of musicians that exemplify the progressive Black musical tradition for social justice in their respective genres of gospel, jazz, soul and spoken word. The methods utilized for my study include a socio-historical account of the origins of Black music, an overview of the artists’ careers, and a lyrical analysis of selected songs created by each of the artists. This study will contribute to the body of literature surrounding the progressive roles, functions and utilities of African American music. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH My mother garners the nickname “gypsy” from her siblings due to the fact that she is always moving and relocating to new and different places. -

Aprilsmokesignal.Pdf

Vol. 63 Issue 8 moke Bands Softball page 4 page 9 Check out the student bands of Hear from the girl’s softball MHS and find out what new CDs ignal team and see when its first are out. game is. Mississinewa High School #1 Indian Trail Gas City, IN Corporation makesS administrative shifts Just a by John Hueston Prom to be held At the start of the 2011-2012 school year, Mrs. Stephanie Lockwood will April 16 at fill the head principal position at MHS and Fabulous 105 Mrs. Lezlie Winter will be at central office as the Director of Curriculum and Educa- by Kristin Cassidy tional Programming. Prom 2011, Just a Dream, is less than three “It definitely will not be same Winter since Mrs. Winter will not be at the high weeks away so any junior or school on a daily basis. She has mentored senior student who wishes to Dream me through my life as my teacher, my attend prom must purchase a principal, and as a fellow administrator,” ticket by April 12. Magical Night-Juniors Danielle Mill and Alison Avery sell Lockwood said. Prom is organized by a prom ticket to junior Lexi Sands. photo by Kristin Cassidy The biggest thing Winter will miss junior class officers and junior about being head principal at MHS is the class sponsers, Ms. Collins and clouds, and a giant moon pre- After prom will be held Mrs. Jones. sented at Fabulous 105 from from 12 a.m. to 3 a.m. at the students. Lockwood “It has been an honor and privi- This year’s prom has the hours of 8 p.m. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

2017MM@M Study Guide

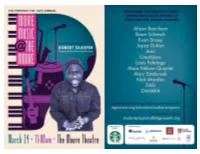

About Us Produced by STG’s Education and Community Programs, More Music @ The Moore (MM@M) is a young artist development program that provides talented young artists (ages 14-21) with the tools and setting to rehearse and perform music under the direction of industry mentors and professionals. The program culminates with two performances at The Moore Theatre, an 11am student matinee and 7:30pm public performance (March 24, 2017). STG is thrilled to welcome Robert Glasper as the Music Director of the 16th annual MM@M. A dynamic producer, composer, and pianist Robert Glasper has won 3 Grammy Awards of his own and contributed to a number of other award winning albums. What sets MM@M apart from other young artist performances is a focus on original work and cross-cultural collaboration. This year, over 150 musicians auditioned to be part of the program, the standard was higher than ever. The 14 selected musicians have come together for 2 months of outside rehearsal before a week of rehearsals at the Moore Theatre to create an innovative, collaborative performance under the artistic direction of Robert Glasper. MM@M is one of a number of STG programs that invests in the next generation of artists in Seattle. STG MISSION: Making performances and arts education in the Pacific Northwest enriching, while keeping Seattle’s historic Paramount, Moore and Neptune Theatres healthy and vibrant. ABOUT EDUCATION: Seattle Theatre Group Education and Community Programs extend beyond The Paramount, Moore and the Neptune Theatre stages and into the lives of the greater Seattle community. STG offered over 1000 programs last seasons impacting 41,695 students and community members from diverse ages and backgrounds. -

November 2009

24 - Twp. Sports The Patriot - W.T.H.S. May, 2011 Township Sports The Patriot Washington Township High School, Boys tennis team seeking success Vol. XVI, Issue 6 529 Hurffville-Cross Keys Road, Sewell, NJ May, 2011 Anthony Dentino ‘11 Of course, experience and even coaching role as varsity members of the team and takes ability can be for naught in any sport if the players their leadership responsibilities seriously. As the harsh winter weather is starting to do not buy into the system. However, it is evident Sharma stated, “As a senior I definitely try give way to the warmth and sunshine, excitement that this is not the case for Washington to encourage the underclassmen as much I can. Sibert’s success Ally Gallo ‘11 is brewing about many of Washington Township Township. While it has certainly been an Tennis can become a very frustrating sport High School’s spring sports teams. And while adjustment period, the players all agree that because your technique has to be dead on, you When walking through the doors of many people associate spring with the ping of Surplus runs the program similarly to Flemming, need to have a good head on your shoulders and Washington Township High School on the first balls flying off of aluminum bats, a certain group and whatever differences there may be, are all a lot of teams [we play throughout the season] day of his freshman year, little did Shane Sibert of athletes is focused on the pop of balls positive. are really tough. Whenever we do exercises I try realize he would be crowned the 2011 Mr.