Ludovico Quaroni's Lesson in Space and the Limits of Visual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Casting Call: Spatial Impressions in the Work of Rachel Whiteread

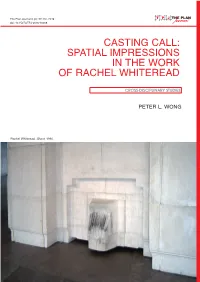

The Plan Journal 0 (0): 97-110, 2016 doi: 10.15274/TPJ-2016-10008 CASTING CALL: SPATIAL IMPRESSIONS IN THE WORK OF RACHEL WHITEREAD CROSS-DISCIPLINARY STUDIES PETER L. WONG Rachel Whiteread, Ghost, 1990. Casting Call: Spatial Impressions in the Work of Rachel Whiteread Peter L. Wong ABSTRACT - For more than 20 years, Rachel Whiteread has situated her sculpture inside the realm of architecture. Her constructions elicit a connection between: things and space, matter and memory, assemblage and wholeness by drawing us toward a reciprocal relationship between objects and their settings. Her chosen means of casting solids from “ready- made” objects reflect a process of visual estrangement that is dependent on the original artifact. The space beneath a table, the volume of a water tank, or the hollow undersides of a porcelain sink serve as examples of a technique that aligns objet-trouvé with a reverence for the everyday. The products of this method, now rendered as space, acquire their own autonomous presence as the formwork of things is replaced by space as it solidifies and congeals. The effect is both reliant and independent, familiar yet strange. Much of the writing about Whiteread’s work occurs in the form of art criticism and exhibition reviews. Her work is frequently under scrutiny, fueled by the popular press and those holding strict values and expectations of public art. Little is mentioned of the architectural relevance of her process, though her more controversial pieces are derived from buildings themselves – e,g, the casting of surfaces (Floor, 1995), rooms (Ghost, 1990 and The Nameless Library, 2000), or entire buildings (House, 1993). -

Watergate Landscaping Watergate Innovation

Innovation Watergate Watergate Landscaping Landscape architect Boris Timchenko faced a major challenge Located at the intersections of Rock Creek Parkway and in creating the interior gardens of Watergate as most of the Virginia and New Hampshire Avenues, with sweeping views open grass area sits over underground parking garages, shops of the Potomac River, the Watergate complex is a group of six and the hotel meeting rooms. To provide views from both interconnected buildings built between 1964 and 1971 on land ground level and the cantilivered balconies above, Timchenko purchased from Washington Gas Light Company. The 10-acre looked to the hanging roof gardens of ancient Babylon. An site contains three residential cooperative apartment buildings, essential part of vernacular architecture since the 1940s, green two office buildings, and a hotel. In 1964, Watergate was the roofs gained in popularity with landscapers and developers largest privately funded planned urban renewal development during the 1960s green awareness movement. At Watergate, the (PUD) in the history of Washington, DC -- the first project to green roof served as camouflage for the underground elements implement the mixed-use rezoning adopted by the District of of the complex and the base of a park-like design of pools, Columbia in 1958, as well as the first commercial project in the fountains, flowers, open courtyards, and trees. USA to use computers in design configurations. With both curvilinear and angular footprints, the configuration As envisioned by famed Italian architect Dr. Luigi Moretti, and of the buildings defines four distinct areas ranging from public, developed by the Italian firm Società Generale Immobiliare semi-public, and private zones. -

The Watergate Project: a Contrapuntal Multi-Use Urban Complex in Washington, Dc

THE WATERGATE PROJECT: A CONTRAPUNTAL MULTI-USE URBAN COMPLEX IN WASHINGTON, DC Adrian Sheppard, FRAIC Professor of Architecture McGill University Montreal Canada INTRODUCTION Watergate is one of North America’s most imaginative and powerful architectural ensembles. Few modern projects of this scale and inventiveness have been so fittingly integrated within an existing and well-defined urban fabric without overpowering its neighbors, or creating a situation of conflict. Large contemporary urban interventions are usually conceived as objects unto themselves or as predictable replicas of their environs. There are, of course, some highly successful exceptions, such as New York’s Rockefeller Centre, which are exemplars of meaningful integration of imposing projects on an existing city, but these are rare. By today’s standards where significance in architecture is measured in terms of spectacle and flamboyance, Watergate is a dignified and rigorous urban project. Neither conventional as an urban design project, nor radical in its housing premise, it is nevertheless as provocative as anything in Europe. Because Moretti grasped the essence of Washington so accurately, he was able to bring to the city a new vision of urbanity. Watergate would prove to be an unequivocally European import grafted unto a typical North-American city, its most remarkable and successful characteristic being its relationship to its immediate context and the city in general. As an urban intervention, Watergate is an inspiring example of how a Roman architect, Luigi Moretti, succeeded in introducing a project of considerable proportions in the fabric of Washington, a city he had never visited before he received the commission. 1 Visually and symbolically, the richness of the traditional city is derived from the fact that there exists a legible distinction and balance between urban fabric and urban monument. -

The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini Valentina Follo University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Follo, Valentina, "The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 858. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/858 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/858 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini Abstract The year 1937 marked the bimillenary of the birth of Augustus. With characteristic pomp and vigor, Benito Mussolini undertook numerous initiatives keyed to the occasion, including the opening of the Mostra Augustea della Romanità , the restoration of the Ara Pacis , and the reconstruction of Piazza Augusto Imperatore. New excavation campaigns were inaugurated at Augustan sites throughout the peninsula, while the state issued a series of commemorative stamps and medallions focused on ancient Rome. In the same year, Mussolini inaugurated an impressive square named Forum Imperii, situated within the Foro Mussolini - known today as the Foro Italico, in celebration of the first anniversary of his Ethiopian conquest. The Forum Imperii's decorative program included large-scale black and white figural mosaics flanked by rows of marble blocks; each of these featured inscriptions boasting about key events in the regime's history. This work examines the iconography of the Forum Imperii's mosaic decorative program and situates these visual statements into a broader discourse that encompasses the panorama of images that circulated in abundance throughout Italy and its colonies. -

The Economic Costs of Civil War: Synthetic Counterfactual Evidence and the Effects of Ethnic Fractionalization 1

H i C N Households in Conflict Network The Institute of Development Studies - at the University of Sussex - Falmer - Brighton - BN1 9RE www.hicn.org The Economic Costs of Civil War: Synthetic Counterfactual Evidence and the Effects of Ethnic Fractionalization 1 Stefano Costalli 2, Luigi Moretti3 and Costantino Pischedda4 HiCN Working Paper 184 September 2014 Abstract: There is a consensus that civil wars entail enormous economic costs, but we lack reliable estimates, due to the endogenous relationship between violence and socio-economic conditions. This paper measures the economic consequences of civil wars with the synthetic control method. This allows us to identify appropriate counterfactuals for assessing the national-level economic impact of civil war in a sample of 20 countries. We find that the average annual loss of GDP per capita is 17.5 percent. Moreover, we use our estimates of annual losses to study the determinants of war destructiveness, focusing on the effects of ethnic heterogeneity. Building on an emerging literature on the relationships between ethnicity, trust, economic outcomes, and conflict, we argue that civil war erodes interethnic trust and highly fractionalized societies pay an especially high “price”, as they rely heavily on interethnic business relations. We find a consistent positive effect of ethnic fractionalization economic war-induced loss. 1 We would like to thank participants at the Conflict Research Society Conference (University of Essex, 2013), the Midwest Political Science Association 72nd Annual Conference (Chicago, 2014), and the European Political Science Association Conference (Edinburgh, 2014) for comments on previous drafts of the paper. The usual disclaimer applies. 2 Stefano Costalli, Department of Government, University of Essex, Wivenhoe Park, Colchester, CO43SQ, United Kingdom. -

MUSSOLINI's ITALIAN and ITALIAN AMERICAN STUDIES Stanislao G

MUSSOLINI'S ITALIAN AND ITALIAN AMERICAN STUDIES Stanislao G. Pugliese Hofstra University Series Editor This publishing initiative seeks to bring the latest scholarship in Italian and Ital ian American history, literature, cinema, and cultural studies to a large audience of specialists, general readers, and students. I&IAS will feature works on mod ern Italy (Renaissance to the present) and Italian American culture and society by established scholars as well as new voices in the academy. This endeavor will help to shape the evolving fields of Italian and Italian American Studies by re emphasizing the connection between the two. The following editorial board of esteemed senior scholars are advisors to the series editor. REBECCA WEST JOHN A. DAVIS University of Chicago University of Connecticut FRED GARDAPHE PHILIP V. CANNISTRARO Stony Brook University Queens College and the Graduate School, CUNY JOSEPHINE GATTUSO HENDIN VICTORIA DeGRAZIA New York University Columbia University Queer Italia: Same-Sex Desire in Italian Literature and Film edited by Gary P. Cestaro July 2004 Frank Sinatra: History, Identity, and Italian American Culture edited by Stanislao G. Pugliese October 2004 The Legacy ofPrimo Levi edited by Stanislao G. Pugliese December 2004 Italian Colonialism edited by Ruth Ben-Ghiat and Mia Fuller July 2005 Mussolini's Rome: Rebuilding the Eternal City Borden W Painter Jr. July 2005 Representing Sacco and Vanzetti edited by Jerome A. Delamater and Mary Ann Trasciatti forthcoming, September 2005 Carlo Tresca: Portrait ofa Rebel Nunzio Pernicone forthcoming, October 2005 MUSSOLINI'S Rebuilding the Eternal City BORDEN W. PAINTER, JR. MUSSOLINI'S ROME Copyright © Borden Painter, 2005. Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2005 978-1-4039-6604-9 All rights reserved. -

Place Victoria: a Joint Venture Between Luigi Moretti and Pier Luigi Nervi

PLACE VICTORIA: A JOINT VENTURE BETWEEN LUIGI MORETTI AND PIER LUIGI NERVI Adrian Sheppard, FRAIC McGill University, Montreal INTRODUCTION lace Victoria stands alone amongst Moretti’s many buildings. The very fact that it deviates ideologically and formally from the rest of his oeuvre makes the project significant and P revelatory of Moretti’s architecture and of the man. The project neither follows the architectural principles of his prewar Rationalist period, nor those of his later expressionist phase. This divergence from his lifelong thinking is more the result of circumstances than the outcome of a re-evaluation of a well-defined design approach. The saga of the design process is a fascinating one for it illustrates how Moretti’s early ideas for the urban skyscraper changed continuously with his increased knowledge and awareness of the problem. He began by attempting to redefine the form and the use of the modern high-rise, but ended with an elegant landmark rather than a breakthrough. Instead of the heroic sculptural object he had hoped to create, he produced a highly functional and very beautiful tower. By Moretti’s earlier (and later) standards, the final version of Place Victoria is a remarkably disciplined and controlled work of architecture in which the usual concerns for self- expression and visual exhilaration are absent. This new formal clarity and structural logic are in great part attributable to his collaborator, engineer, Pier Luigi Nervi. The concept of Place Victoria is the outcome of a coming together of a radical architect and a conservative engineer. In culture and temperament, Nervi and Moretti were opposites. -

The Architect Luigi Moretti. from Rationalism to Informalism1

Jedno z ostatnich zdj B4 architekta zrobionych pod nowy, strukturalny paradygmat tworzenia architek- koniec bycia to podsumowanie, czy mo be raczej wi- tury, który realn = nieci =goV4 form przeciwstawia zja Vwiata kultury Luigiego Morettiego (il. 53). Ar- ich poza realnej ci =goVci, tak jak ci Bb ar materialnej chitekt fotografuje si B z makiet = Palazzo dei Conser- rzeczywisto Vci – lekko Vci jej obrazu, aby stworzy 4 vatori, symbolem bliskiego zwi =zku jego prac z hi- rodzaj architektury marze L, która b Bdzie w stanie stori =, trzyma uformowany w kul B zwój metalowych dostarczy 4 prze by4 najintensywniejszych, jakich do- pasków od Claire Falkenstein, wyra baj =cy emocjo- zna 4 jeste Vmy w stanie, nazwanych przez Morettie- nalny zwi =zek z nowoczesn = sztuk = l‘art informel , go - incantamento – zakl Bciem, bo to ono stanowi przed nim stoi makieta [ lara z Fiuggi, obrazuj =ca gówny cel sztuki. Tumaczenie I. Szyma Lska, D. K osek-Koz owska Annalisa Viati Navone, dr arch. Archivio del Moderno Accademia di Architettura Università della Svizzera italiana Mendrisio THE ARCHITECT LUIGI MORETTI. FROM RATIONALISM TO INFORMALISM 1 ANNALISA VIATI NAVONE Many pictures portray Luigi Moretti in his materials, which led him to a kind of Informal elegant, enormous and famous of [ ce extended Art called «materic». Many artists of this circle on two \ oors of Palazzo Colonna, rented from were fascinated with gestural art (action painting), the Colonna Princes, near Piazza Venezia, in the among them Lucio Fontana, the famous author historical heart of Rome. This was the place where of cuts, Jackson Pollock with his drippings, and Moretti spent most of his life, his of [ ce, but at the Georges Mathieu, author of abstract compositions same time his home, where he kept his great art made by repeating a few signs many times on the collection and his very rich library, in the 1960s used canvas. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NFS Form 10-900 (Rev. 11-90) Y5&2&\ \Opafto.l0024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties or districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to compete all items. 1. Name of Property______________________________________________ Historic name: Watergate______________________________________________ Other names/site number:_________________________________________________ 2. T vocation____________________________________________________ Street fc Number 2500^ 7.6003 2650. 7.600 Virginia Avemie3 N.W.; 6003 700 New Hampshire Avenue., N.W.__________________________________[ ] Not for Publication_____ City or town: Washington_____________________[ ] Vicinity___________________ State: DC________Code- 001 County_________Code:______Zip Code: 20037______ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification__________________________________ -

PIER LUIGI NERVI Art and Science of Building • the TRAVELING EXHIBITION •

PIER LUIGI NERVI Art and Science of Building • THE TRAVELING EXHIBITION • a project by Comunicarch Associates with PLN project Who is Pier Luigi Nervi? Why an exhibition For whom? The international exhibition on Pier Luigi Nervi? After the successes of previous “Pier Luigi Nervi. Art and Internationally esteemed and editions, the exhibition was Science of Building” celebrates praised during his lifetime, after transformed in 2014 in a light the life and work of one of the his death in 1979 the work of format and it will embark in a greatest and most inventive Pier Luigi Nervi fell into a period wide international tour towards structural engineers of the 20th of oblivion and it is only in recent other prospective locations in century, the Italian Pier Luigi years that extensive research Asia, North America and other Nervi (1891-1979). into his work has recommenced. parts of the world to celebrate With his masterpieces, In 2010, to commemorate the not only the genius and scattered the world over, Nervi thirtieth anniversary of Nervi’s inventiveness of Pier Luigi Nervi, contributed to create a glorious death, an international itinerant but also his genuine period for structural exhibition was developed. This international spirit, as a architecture. Nikolaus Pevsner, work marks the outcome of a designer, builder and educator. the distinguished historian of multifaceted research project Such an extended analysis and architecture, described him as that assembled a vast team of critical appraisal of Nervi’s “the most brilliant artist in scholars, with the aim of work is expected to offer a reinforced concrete of our time”. -

Rascacielos a La Italiana. Construcción De Gran Altura En Los Años Cincuenta Y Sesenta

Informes de la Construcción Vol. 72, 558, e342 abril-junio 2020 ISSN-L: 0020-0883 https://doi.org/10.3989/ic.71572 Italian style skyscrapers. High-rise construction in the fifties and sixties Rascacielos a la italiana. Construcción de gran altura en los años cincuenta y sesenta G. Capurso (*) ABSTRACT In the fifties and sixties, while Italian engineering was receiving important international awards, the theme of the tall building attracted the attention of the best architects. They made it a field of design experimentation, immediately sensing how the strategic use of the structure could revolutionize the already stereotyped image of the all-steel and glass towers proposed by the International Style. Gio Ponti, Luigi Moretti and the BBPR thus created formidable partnerships with Pier Luigi Nervi and Arturo Danusso, the most active engineers in the field of skyscraper design. The result was at least three masterpieces, among the works created in those years: the Velasca tower and the Pirelli skyscraper in Milan and the Stock Exchange tower in Montreal, which, at the time of its completion, also marked the record for the highest reinforced concrete building in the world. Keywords: Italian Engineering, skyscrapers, structures, reinforced concrete, Pier Luigi Nervi, Arturo Danusso, Italian Style, International Style, Construction History, SIXXI research project. RESUMEN En los años cincuenta y sesenta del siglo XX, mientras la ingeniería italiana recibía importantes premios internacionales, el diseño de los edificios en altura atraía la atención de los mejores arquitectos. Estos entendieron inmediatamente lo mucho que el empleo estratégico de la estructura habría podido revolucionar la ya de por sí estereotipada imagen de la torre de acero y vidrio propuesta por el Estilo Internacional, y lo convirtieron en un campo de experimentación. -

To Understand Luigi Moretti, the Man and the Architect, One Must

LUIGI MORETTI: A TESTIMONY Adrian Sheppard, FRAIC Professor of Architecture McGill University, Montreal MEETING MORETTI I first encountered Luigi Moretti in Rome in the summer of 1961 when seeking work as an architect. I learned that Moretti had recently received a commission to design a complex of high-rise towers in Montreal, and the idea of working for an Italian architect designing a project in my hometown appealed to me for obvious reasons. I had initially planned on spending three months in Rome, getting to know the city and its architecture but these three months were to become six months, then twelve, and finally two years. I arrived at Moretti’s office on the appointed day, after siesta, and was ushered into an elegant room. The space, comfortable and lived-in, was dominated by a large desk laden with objets d’art, sculptures, drawings, books, periodicals, and jars of pencils and paintbrushes. The walls of the office were covered with paintings, both modern and old. Behind the desk were a large Baroque painting and an abstract canvas by Mathieu. I found myself before a man of considerable physical proportions, with a powerful gaze, slow demeanour, and a sad and melancholic expression. Moretti received me with great reserve and formality. We spoke in French and after a lengthy introductory discussion, touching on the state of architecture in Montreal and my understanding and appreciation of Modernism, Moretti looked at my portfolio and asked why I wanted to work in Rome, and why with him? Upon learning that I had some experience in the design of high-rise building in Montreal and London1, Moretti indicated that he would like me to work on two projects, the Place Victoria Tower in Montreal and, at a later date, the Watergate Project in Washington, DC.2 THE MAN Moretti’s imposing physicality extended itself to all aspects of his life, and was most manifest in his body language.