MUSSOLINI's ITALIAN and ITALIAN AMERICAN STUDIES Stanislao G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Casting Call: Spatial Impressions in the Work of Rachel Whiteread

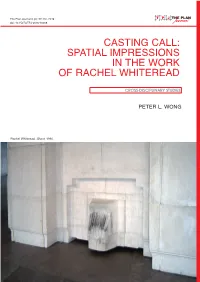

The Plan Journal 0 (0): 97-110, 2016 doi: 10.15274/TPJ-2016-10008 CASTING CALL: SPATIAL IMPRESSIONS IN THE WORK OF RACHEL WHITEREAD CROSS-DISCIPLINARY STUDIES PETER L. WONG Rachel Whiteread, Ghost, 1990. Casting Call: Spatial Impressions in the Work of Rachel Whiteread Peter L. Wong ABSTRACT - For more than 20 years, Rachel Whiteread has situated her sculpture inside the realm of architecture. Her constructions elicit a connection between: things and space, matter and memory, assemblage and wholeness by drawing us toward a reciprocal relationship between objects and their settings. Her chosen means of casting solids from “ready- made” objects reflect a process of visual estrangement that is dependent on the original artifact. The space beneath a table, the volume of a water tank, or the hollow undersides of a porcelain sink serve as examples of a technique that aligns objet-trouvé with a reverence for the everyday. The products of this method, now rendered as space, acquire their own autonomous presence as the formwork of things is replaced by space as it solidifies and congeals. The effect is both reliant and independent, familiar yet strange. Much of the writing about Whiteread’s work occurs in the form of art criticism and exhibition reviews. Her work is frequently under scrutiny, fueled by the popular press and those holding strict values and expectations of public art. Little is mentioned of the architectural relevance of her process, though her more controversial pieces are derived from buildings themselves – e,g, the casting of surfaces (Floor, 1995), rooms (Ghost, 1990 and The Nameless Library, 2000), or entire buildings (House, 1993). -

Michelangelo's Locations

1 3 4 He also adds the central balcony and the pope’s Michelangelo modifies the facades of Palazzo dei The project was completed by Tiberio Calcagni Cupola and Basilica di San Pietro Cappella Sistina Cappella Paolina crest, surmounted by the keys and tiara, on the Conservatori by adding a portico, and Palazzo and Giacomo Della Porta. The brothers Piazza San Pietro Musei Vaticani, Città del Vaticano Musei Vaticani, Città del Vaticano facade. Michelangelo also plans a bridge across Senatorio with a staircase leading straight to the Guido Ascanio and Alessandro Sforza, who the Tiber that connects the Palace with villa Chigi first floor. He then builds Palazzo Nuovo giving commissioned the work, are buried in the two The long lasting works to build Saint Peter’s Basilica The chapel, dedicated to the Assumption, was Few steps from the Sistine Chapel, in the heart of (Farnesina). The work was never completed due a slightly trapezoidal shape to the square and big side niches of the chapel. Its elliptical-shaped as we know it today, started at the beginning of built on the upper floor of a fortified area of the Apostolic Palaces, is the Chapel of Saints Peter to the high costs, only a first part remains, known plans the marble basement in the middle of it, space with its sail vaults and its domes supported the XVI century, at the behest of Julius II, whose Vatican Apostolic Palace, under pope Sixtus and Paul also known as Pauline Chapel, which is as Arco dei Farnesi, along the beautiful Via Giulia. -

San Giovanni Report

San Giovanni Living Next to a Transit Corridor Brooke Shin Madeleine Galvin Raphael Laude Shareef Hussam Rome Workshop 00 Introduction San Giovanni in the urban context of Rome Image Subject Rome Workshop Outline Contents 00 Introduction 1 Outline Getting Oriented A Transit Corridor Methodology Hypotheses 01 History 15 Summary Timeline A Plan for San Giovanni Construction Begins A Polycentric Plan Metro Construction 02 Statistics 19 Summary Key Data Points Demographics & Housing Livability Audit 03 Built Form 25 Summary Solids Voids Mobility 04 Services 37 Summary Ground-Floor Use Primary Area Services Secondary Area Services Institutions 05 Engagement 49 Summary Key Stakeholders Intercept Interviews Cognitive Mapping 06 Conclusion 57 Key Takeaways Next Steps Bibliography, Appendix 3 Introduction Graphics / Tables Images Urban Context Study Area Broader / Local Transit Network 1909 Master Plan 1936 Historical Map 1962 Master Plan Population Density Population Pyramids Educational Attainment Homeownership San Giovanni Transit Node Building Typologies/Architectural Styles Public Spaces Sidewalks, Street Typologies, Flows Primary Area Services Secondary Area Services Ground Floor Use Map Daily Use Services Livability Audit Key 4 Rome Workshop Introduction The Rome Workshop is a fieldwork-based course that takes students from the classroom to the city streets in order to conduct a physical assess- ment of neighborhood quality. Determining the child and age-friendliness of public spaces and services was the main goal of this assessment. The San Giovanni neighborhood starts at the Por- ta San Giovanni and continues over two kilome- ters south, but this study focused specifically on the area that flanks the Aurelian Walls, from the Porta San Giovanni gate to the Porta Metronio gate. -

Falda's Map As a Work Of

The Art Bulletin ISSN: 0004-3079 (Print) 1559-6478 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcab20 Falda’s Map as a Work of Art Sarah McPhee To cite this article: Sarah McPhee (2019) Falda’s Map as a Work of Art, The Art Bulletin, 101:2, 7-28, DOI: 10.1080/00043079.2019.1527632 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2019.1527632 Published online: 20 May 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 79 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcab20 Falda’s Map as a Work of Art sarah mcphee In The Anatomy of Melancholy, first published in the 1620s, the Oxford don Robert Burton remarks on the pleasure of maps: Methinks it would please any man to look upon a geographical map, . to behold, as it were, all the remote provinces, towns, cities of the world, and never to go forth of the limits of his study, to measure by the scale and compass their extent, distance, examine their site. .1 In the seventeenth century large and elaborate ornamental maps adorned the walls of country houses, princely galleries, and scholars’ studies. Burton’s words invoke the gallery of maps Pope Alexander VII assembled in Castel Gandolfo outside Rome in 1665 and animate Sutton Nicholls’s ink-and-wash drawing of Samuel Pepys’s library in London in 1693 (Fig. 1).2 There, in a room lined with bookcases and portraits, a map stands out, mounted on canvas and sus- pended from two cords; it is Giovanni Battista Falda’s view of Rome, published in 1676. -

Watergate Landscaping Watergate Innovation

Innovation Watergate Watergate Landscaping Landscape architect Boris Timchenko faced a major challenge Located at the intersections of Rock Creek Parkway and in creating the interior gardens of Watergate as most of the Virginia and New Hampshire Avenues, with sweeping views open grass area sits over underground parking garages, shops of the Potomac River, the Watergate complex is a group of six and the hotel meeting rooms. To provide views from both interconnected buildings built between 1964 and 1971 on land ground level and the cantilivered balconies above, Timchenko purchased from Washington Gas Light Company. The 10-acre looked to the hanging roof gardens of ancient Babylon. An site contains three residential cooperative apartment buildings, essential part of vernacular architecture since the 1940s, green two office buildings, and a hotel. In 1964, Watergate was the roofs gained in popularity with landscapers and developers largest privately funded planned urban renewal development during the 1960s green awareness movement. At Watergate, the (PUD) in the history of Washington, DC -- the first project to green roof served as camouflage for the underground elements implement the mixed-use rezoning adopted by the District of of the complex and the base of a park-like design of pools, Columbia in 1958, as well as the first commercial project in the fountains, flowers, open courtyards, and trees. USA to use computers in design configurations. With both curvilinear and angular footprints, the configuration As envisioned by famed Italian architect Dr. Luigi Moretti, and of the buildings defines four distinct areas ranging from public, developed by the Italian firm Società Generale Immobiliare semi-public, and private zones. -

Museo Delle Mura Passeggiata Da Porta San Sebastiano a Via C

Municipio I copertura costituita da una volta a vela con una particolare da notare, infine, due stemmi papali: uno, fra le torri 5 e tessitura di mattoni, e l'assenza della scala di accesso alla 6, ricorda i restauri di Alessandro VI (1492 - 1507) d P camera superiore. a a La terza torre nel XV sec. fu usata, probabilmente, come P o luogo di ritiro di un eremita che lasciò a ricordo l'immagine s r t di una Madonna con Bambino, dipinta sul muro all'uscita s a della torre. La galleria che porta verso la torre 4 conserva la S e pavimentazione originaria con al centro una fessura che a g indica l'attacco fra la struttura di Aureliano e quella di n S Onorio, aggiunta per allargare la piattaforma su cui g e b costruire i pilastri e le arcate della galleria. La parete i a frontale della quarta torre crollò e fu ricostruita in età a s t medioevale in posizione più arretrata restringendone così t i a la camera di manovra; stessa cosa accadde nelle torri 6 e 7 a n o dove il restauro medioevale ridusse la camera ad un l u semplice passaggio. a v In alcuni punti lungo il cammino di ronda si possono notare n i a delle feritoie di forma quadrata che furono così trasformate g nel 1848 per adattarle alla fucileria, quando le mura furono C . o teatro di scontri durante la Repubblica Romana. C o Nell'ottava torre si può notare la copertura a volta rivestita di l l e laterizi come quella vista nella torre 2 del tratto in esame, o m mentre la nona torre ha perso del tutto la struttura originaria M b all'interno e all'esterno, manca anche la copertura della o camera le cui pareti sono costituite da murature medievali, u del XIX sec. -

January 2006 ********** February 2006 ********** March 2006

January 2006 Sunday, 1st January 2006 - 11.00 am Via della Conciliazione - St. Peter's Square - Rome NEW YEAR'S DAY PARADE With the participation of: University of Nebraska Marching Band Rioni di Cori Flag Throwers Banda del Comune di Recanati Banda della Aeronautica Militare Friday, 6th January 2006 - 9.00 pm Church S. Ignazio, Piazza S. Ignazio - Rome Benedictine College Choir USA Program: sacred choir music Sunday, 22nd January 2006 – 5.00 pm Church S. Cipriano, Via di Torrevecchia 169 - Rome St. Cyprian Liturgical Choir - USA Iubilate Deo - Italy Program: sacred choir music ********** February 2006 Tuesday, 21st February 2006 - 9.00 pm Church S. Rufino, P. zza S. Rufino, Assisi Abbotts Bromley School Chapel Choir United Kingdom Program: Schubert, Elgar, Kodaly ********** March 2006 Sunday, 12th March 2006 - 9.00 pm Church S. Ignazio, Piazza S. Ignazio - Rome Curé of Ars Church Choir USA 1 Program: sacred choir music Tuesday, 14th March 2006 - 9.00 pm Church S. Ignazio, Piazza S. Ignazio - Rome Holy Trinity Church Choir USA Program: sacred choir music Sunday, 19th March 2006 - 9.00 pm Church S. Ignazio, Piazza S. Ignazio - Rome Cathedral of St. James’s Choir USA Program: sacred choir music Saturday, 25th March 2006 - 9.00 pm Auditorium Parco della Musica - Petrassi Hall Viale Pietro De Coubertin - Rome Sant'Ignazio di Loyola an Eighteenth Century chamber music piece by Domenico Zipoli S.J., Martin Schmid S.J., Anonymous Ensemble Abendmusik Interpreters: Randall Wong, Robin Blaze, Patricia Vaccari, Nicola Pascoli, Marco Andriolo, Mira Andriolo Conductor: John Finney Reservation required - Tel. nr. 0039 329 2395598 Sunday, 26th March 2006 - 5.00 pm Church Sant'Andrea al Quirinale - Via del Quirinale - Rome Sant'Ignazio di Loyola an Eighteenth Century chamber music piece by Domenico Zipoli S.J., Martin Schmid S.J., Anonymous Ensemble Abendmusik Interpreters: Randall Wong, Robin Blaze, Patricia Vaccari, Nicola Pascoli, Marco Andriolo, Mira Andriolo Conductor: John Finney Reservation required - Tel. -

The Janus Arch

Proceedings of the 38th Annual Conference on Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology, CAA2010 F. Contreras, M. Farjas and F.J. Melero (eds.) Digital Mediation from Discrete Model to Archaeological Model: the Janus Arch Ippolito, A.1, Borgogni, F.1, Pizzo, A.2 1 Dpto. RADAAr Università di Roma “Sapienza”, Italy 2 Instituto de Arqueologia (CSIC, Junta de Extremadura, Consorcio de Mérida), Spain [email protected]; [email protected] ; [email protected] Survey operations and the representation of acquired data should today be considered as consolidated. New acquisition methods such as point clouds obtained using 3D laser scanners are also part of today’s scenario. The scope of this paper is to propose a protocol of operations based on extensive previous experience and work to acquire and elaborate data obtained using complex 3D survey. This protocol focuses on illustrating the methods used to turn a numerical model into a system of two-dimensional and three-dimensional models that can help to understand the object in question. The study method is based on joint practical work by architects and archaeologists. The final objective is to create a layout that can satisfy the needs of scholars and researchers working in different disciplinary fields. The case study in this paper is the Arch of Janus in Rome near the Forum Boarium. The paper will illustrate the entire acquisition process and method used to transform the acquired data after the creation of a model. The entire operation was developed in close collaboration between the RADAAr Dept., University of Rome “Sapienza,” Italy and the Istituto de Arqueologia (CSIC, Junta de Extremadura, Consorcio de Mérida), Spain. -

C HAPTER THREE Dissertation I on the Waters and Aqueducts Of

Aqueduct Hunting in the Seventeenth Century: Raffaele Fabretti's De aquis et aquaeductibus veteris Romae Harry B. Evans http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=17141, The University of Michigan Press C HAPTER THREE Dissertation I on the Waters and Aqueducts of Ancient Rome o the distinguished Giovanni Lucio of Trau, Raffaello Fabretti, son of T Gaspare, of Urbino, sends greetings. 1. introduction Thanks to your interest in my behalf, the things I wrote to you earlier about the aqueducts I observed around the Anio River do not at all dis- please me. You have in›uenced my diligence by your expressions of praise, both in your own name and in the names of your most learned friends (whom you also have in very large number). As a result, I feel that I am much more eager to pursue the investigation set forth on this subject; I would already have completed it had the abundance of waters from heaven not shown itself opposed to my own watery task. But you should not think that I have been completely idle: indeed, although I was not able to approach for a second time the sources of the Marcia and Claudia, at some distance from me, and not able therefore to follow up my ideas by surer rea- soning, not uselessly, perhaps, will I show you that I have been engaged in the more immediate neighborhood of that aqueduct introduced by Pope Sixtus and called the Acqua Felice from his own name before his ponti‹- 19 Aqueduct Hunting in the Seventeenth Century: Raffaele Fabretti's De aquis et aquaeductibus veteris Romae Harry B. -

Writing Rome

TRAVEL SEMINAR TO ROME JACKIE MURRAY “Writing Rome” (TX201) is a one-credit travel seminar that will introduce students to interdisciplinary perspectives on Rome. “All roads lead to Rome.” This maxim guides our study tour of the Eternal City. In “Writing Rome” students will travel to KAITLIN CURLEY ANDERS, Rome and compare the city constructed in texts with the city constructed of brick, concrete, marble, wood, and metal. This travel seminar will offer tours of the major ancient sites (includ- ing the Fora, the Palatine, the Colosseum, the Pantheon), as well as the Vatican, the major museums, churches and palazzi, Fascist monuments, the Jewish quarter and other locales ripe with the PHOTOS BY: DAN CURLEY, DAN CURLEY, PHOTOS BY: historical and cultural layering that is the city’s hallmark. In addi- OFF-CAMPUS STUDY & EXCHANGES tion, students will keep travel journals and produce a culminat- ing essay (or other written work) about their experiences on the tour, thereby continuing the tradition of writing Rome. WHY ROME? Rome is the Eternal City, a cradle of western culture, and the root of the English word “romance.” Founded on April 21, 753 BCE (or so tradition tells us), the city was the heart of the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, and today serves as the capitol of Italy. Creative Thought Matters Bustling, dense, layered, and sublime, Rome has withstood tyrants, invasions, disasters, and the ravages of the centuries. The Roman story is the story of civilization itself, with chapters ? written by citizens and foreigners alike. Now you are the author. COURSE SCHEDULE “Reading Rome,” the 3-credit lecture and discussion-based course, will be taught on the Skidmore College campus during the Spring 2011 semester. -

Reflections of Italy November 4 – 13, 2020

Windsor Locks Senior Center presents… Reflections of Italy November 4 – 13, 2020 Book Now & Save $200 Per Person SPECIAL TRAVEL PRESENTATION Date: Thursday, November 7, 2019 Time: 10:00 AM Windsor Locks Senior Center, 41 Oak St. Windsor Locks, CT 06096 For more information contact Sherry Townsend, Windsor Locks Senior Center (860) 627-1426 [email protected] Day 1: Wednesday, November 4, 2020 Overnight Flight Welcome to Italy, a land rich in history, culture, art and romance. Your journey begins with an overnight flight. Day 2: Thursday, November 5, 2020 Rome, Italy - Tour Begins We begin in Rome, the “Eternal City.” This evening, join your fellow travelers for a special welcome dinner at a popular local restaurant featuring regional delicacies and fine Italian wines. (D) Day 3: Friday, November 6, 2020 Rome This morning, a locally guided tour of Classical Rome will allow you to discover famous sights such as the Baths of Caracalla, the legendary Aventine and Palatine Hills, the ancient Circus Maximus, and the Arch of Constantine. During an in-depth visit to the Colosseum, your guide recounts its rich history. The remainder of the day is at leisure. Perhaps a trip to Vatican City, with an optional tour to the Vatican Museums and St. Peter's Basilica,* will be on your personal sightseeing list. (B) Day 4: Saturday, November 7, 2020 Rome - Assisi - Perugia/Assisi Ease your way into the local culture as your Tour Manager shares a few key Italian phrases. Travel to Assisi, birthplace of St. Francis. Take in the old-world atmosphere on a guided walking tour of the old city, including the Basilica of St. -

Progetto Per Un Parco Integrato Delle Mura Storiche

ROMA PARCO INTEGRATO DELLE MURA STORICHE Mura Aureliane - Mura da Paolo III a Urbano VIII Esterno delle Mura lungo viale Metronio Mura storiche di Roma 2 Pianta di Roma di Giovanni Battista Nolli - 1748 3 Mura di Roma, Grande Raccordo Anulare e anello ciclabile 4 Piano Regolatore Generale di Roma - 2003/2008 5 Ambiti di programmazione strategica: quadro di unione 1-Tevere 2-Mura 3-Anello ferroviario 1 4-Parco dell’Appia 5-Asse nord-sud 5 2 3 4 6 Pianta di Pietro Visconti (Archeologo) e Carlo Pestrini (Incisore)- 1827 7 Quadro di unione Forma Urbis Romae di Rodolfo Lanciani - 1893/1901 8 Piano Regolatore Generale di Roma - 1883 9 Piano Regolatore Generale di Roma - 1909 10 Piano Regolatore Generale di Roma - 1931 11 Piano Regolatore Generale di Roma - 1961 12 Stralcio Piano Regolatore Generale di Roma - 1961 13 Intersezioni delle Mura con gli assi viari storici e ambiti di progettazione 2 1 - Corso_Flaminia 2 - XX Settembre_Salario 3 - Laterano_Appio 4 - Caracalla_Appia Antica 1 5 - Marmorata_Ostiense 6 - Trastevere_Gianicolo Aurelia antica 6 5 3 4 14 Centralità lungo le Mura storiche 15 Parchi e ambiti di valorizzazione ambientale Villa Borghese Villa Doria Pamphili Parco dell’Appia 16 Ambito di programmazione strategica Mura - Risorse 17 Ambito di programmazione strategica Mura - Obiettivi 18 Progetto «Porte del Tempo» Museo del Sito UNESCO a Porta del Museo dei Bersaglieri Popolo di Porta Pia Museo garibaldino e repubblica Romana a Porta Portese e Porta San Pancrazio Museo delle Mura Museo della resistenza a Porta San a Porta Ostiense Sebastiano 19 Porta del Popolo (Flaminia) 20 Porta San Sebastiano (Appia Antica) 21 Porta San Paolo (Ostiense) 22 Parco lineare integrato 23 Schema direttore generale del progetto urbano delle Mura 24 Parco lineare integrato delle Mura - Progetti realizzati e approvati Responsabili del procedimento: Arch.