Place Victoria: a Joint Venture Between Luigi Moretti and Pier Luigi Nervi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CTBUH Technical Paper

CTBUH Technical Paper http://technicalpapers.ctbuh.org Subject: Other Paper Title: Talking Tall: The Global Impact of 9/11 Author(s): Klerks, J. Affiliation(s): CTBUH Publication Date: 2011 Original Publication: CTBUH Journal 2011 Issue III Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat/Author(s) CTBUH Journal International Journal on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat Tall buildings: design, construction and operation | 2011 Issue III Special Edition World Trade Center: Ten Years On Inside Case Study: One World Trade Center, New York News and Events 36 Challenging Attitudes on 14 “While, in an era of supertall buildings, big of new development. The new World Trade Bridging over the tracks was certainly an Center Transportation Hub alone will occupy engineering challenge. “We used state-of-the- numbers are the norm, the numbers at One 74,300 square meters (800,000 square feet) to art methods of analysis in order to design one Codes and Safety serve 250,000 pedestrians every day. Broad of the primary shear walls that extends all the World Trade are truly staggering. But the real concourses (see Figure 2) will connect Tower way up the tower and is being transferred at One to the hub’s PATH services, 12 subway its base to clear the PATH train lines that are 02 This Issue story of One World Trade Center is the lines, the new Fulton Street Transit Center, the crossing it,” explains Yoram Eilon, vice Kenneth Lewis Nicholas Holt World Financial Center and Winter Garden, a president at WSP Cantor Seinuk, the structural innovative solutions sought for the ferry terminal, underground parking, and retail engineers for the project. -

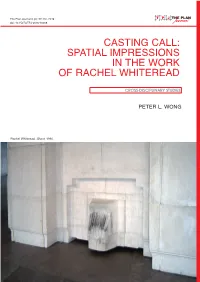

Casting Call: Spatial Impressions in the Work of Rachel Whiteread

The Plan Journal 0 (0): 97-110, 2016 doi: 10.15274/TPJ-2016-10008 CASTING CALL: SPATIAL IMPRESSIONS IN THE WORK OF RACHEL WHITEREAD CROSS-DISCIPLINARY STUDIES PETER L. WONG Rachel Whiteread, Ghost, 1990. Casting Call: Spatial Impressions in the Work of Rachel Whiteread Peter L. Wong ABSTRACT - For more than 20 years, Rachel Whiteread has situated her sculpture inside the realm of architecture. Her constructions elicit a connection between: things and space, matter and memory, assemblage and wholeness by drawing us toward a reciprocal relationship between objects and their settings. Her chosen means of casting solids from “ready- made” objects reflect a process of visual estrangement that is dependent on the original artifact. The space beneath a table, the volume of a water tank, or the hollow undersides of a porcelain sink serve as examples of a technique that aligns objet-trouvé with a reverence for the everyday. The products of this method, now rendered as space, acquire their own autonomous presence as the formwork of things is replaced by space as it solidifies and congeals. The effect is both reliant and independent, familiar yet strange. Much of the writing about Whiteread’s work occurs in the form of art criticism and exhibition reviews. Her work is frequently under scrutiny, fueled by the popular press and those holding strict values and expectations of public art. Little is mentioned of the architectural relevance of her process, though her more controversial pieces are derived from buildings themselves – e,g, the casting of surfaces (Floor, 1995), rooms (Ghost, 1990 and The Nameless Library, 2000), or entire buildings (House, 1993). -

Spring Office Market Report 2018 Greater Montreal

SPRING OFFICE MARKET REPORT 2018 GREATER MONTREAL Image Credit: Avison Young Québec Inc. PAGE 1 SPRING 2018 OFFICE MARKET REPORT | GREATER MONTREAL SPRING OFFICE MARKET REPORT 2018 GREATER MONTREAL Office market conditions have Class-A availability Downtown been very stable in the Greater Montreal reached 11.7% at the Montreal Area (GMA) over the end of the first quarter, which past year, but recent news lead represents an increase of only 20 to believe this could change basis points year-over-year. drastically over the years to come as major projects were announced Landlords who invested in their and the construction of Montreal’s properties and repositioned their Réseau Express Métropolitain assets in Downtown Montreal over (REM) began. New projects and the past years are benefiting from future developments are expected their investments as their portfolios to shake up Montreal’s real estate show more stability and success markets and put a dent in the than most. stability observed over the past quarters. It is the case at Place Ville Marie, where Ivanhoé Cambridge is Even with a positive absorption of attracting new tenants who nearly 954,000 square feet (sf) of are typically not interested in space over the last 12 months, the traditional office space Downtown total office availability in the GMA Montreal, such as Sid Lee, who will remained relatively unchanged be occupying the former banking year-over-year with the delivery of halls previously occupied by the new inventory, reaching 14.6% at Royal Bank of Canada. Vacancy and the end of the first quarter of 2018 availability in the iconic complex from 14.5% the previous year. -

Cahiers De Géographie Du Québec

Document généré le 24 sept. 2021 23:27 Cahiers de géographie du Québec Le nouveau centre-ville de Montréal Clément Demers Volume 27, numéro 71, 1983 Résumé de l'article Le centre-ville de Montréal vient de connaître un boom immobilier qui n'a URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/021609ar d'égal que celui des années 1960-62. Cette activité fébrile sera suivie d'un DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/021609ar inévitable ralentissement, puis d'une éventuelle reprise. Les bâtiments publics et privés qui viennent d'être construits ont en quelque sorte refaçonné Aller au sommaire du numéro certaines parties du quartier. Cette transformation s'inscrit dans le prolongement du développement des décennies précédentes, bien qu'elle présente certaines particularités à divers points de vue. Le présent article Éditeur(s) effectue l'analyse de cette récente relance et propose certaines réflexions sur l'avenir du centre-ville de Montréal. Département de géographie de l'Université Laval ISSN 0007-9766 (imprimé) 1708-8968 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Demers, C. (1983). Le nouveau centre-ville de Montréal. Cahiers de géographie du Québec, 27(71), 209–235. https://doi.org/10.7202/021609ar Tous droits réservés © Cahiers de géographie du Québec, 1983 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. -

Review Market Report 2017 Greater Montreal Area

YEAR-END OFFICE REVIEW MARKET REPORT 2017 GREATER MONTREAL AREA PAGE 1 2017 YEAR-END REVIEW OFFICE MARKET REPORT | GREATER MONTREAL YEAR-END OFFICE REVIEW MARKET REPORT 2017 GREATER MONTREAL AREA 2017 proved to be a very successful 15.5% to 14.7%. The GMA’s vacancy year for the Greater Montreal Area, rate is expected to tick back up as the Province’s unemployment over the next months, as many rates dropped to unprecedented mixed-use and office projects are lows and the city’s economy currently under construction on thrived in numerous activity and off-island. sectors. Artificial intelligence (AI) stole the spotlight last year, as Overall, the average net rental rates Montreal is becoming a growing in the GMA remained relatively hub for AI. The city is now home unchanged over the past year, to AI research laboratories from hovering around $14.00 per square Microsoft, Facebook, Google, foot (psf) for all office classes, while Samsung and Thales, and local- the additional rates remained in based AI players such as Element the vicinity of $13.00 psf. However, AI keep on expanding at a the gap between rental rates in drastic pace. The metropolitan the Downtown core and the other area maintained the sustained submarkets remains significant, as economic growth witnessed over net rental rates in the central areas the past years in 2017, leaning are closer to $17.00 psf and the towards an optimistic outlook for additional rents are approaching the years to come. $18.00 psf. From an office market perspective, The demand for quality office there has been a healthy decrease space in the Downtown Core is in available space, slightly shifting improving. -

Watergate Landscaping Watergate Innovation

Innovation Watergate Watergate Landscaping Landscape architect Boris Timchenko faced a major challenge Located at the intersections of Rock Creek Parkway and in creating the interior gardens of Watergate as most of the Virginia and New Hampshire Avenues, with sweeping views open grass area sits over underground parking garages, shops of the Potomac River, the Watergate complex is a group of six and the hotel meeting rooms. To provide views from both interconnected buildings built between 1964 and 1971 on land ground level and the cantilivered balconies above, Timchenko purchased from Washington Gas Light Company. The 10-acre looked to the hanging roof gardens of ancient Babylon. An site contains three residential cooperative apartment buildings, essential part of vernacular architecture since the 1940s, green two office buildings, and a hotel. In 1964, Watergate was the roofs gained in popularity with landscapers and developers largest privately funded planned urban renewal development during the 1960s green awareness movement. At Watergate, the (PUD) in the history of Washington, DC -- the first project to green roof served as camouflage for the underground elements implement the mixed-use rezoning adopted by the District of of the complex and the base of a park-like design of pools, Columbia in 1958, as well as the first commercial project in the fountains, flowers, open courtyards, and trees. USA to use computers in design configurations. With both curvilinear and angular footprints, the configuration As envisioned by famed Italian architect Dr. Luigi Moretti, and of the buildings defines four distinct areas ranging from public, developed by the Italian firm Società Generale Immobiliare semi-public, and private zones. -

1, PLACE VILLE MARIE MONTRÉAL (Québec)

1, PLACE VILLE MARIE MONTRÉAL (Québec) BUILDING SPECIFICATIONS Montreal’s iconic 46-storey cruciform-shaped tower offers the most prestigious and vibrant working any employee need is met or exceeded using the latest in ongoing environment available in the city. Thousands of people emerge daily from Montreal’s famous sustainable development practices. The Plave Ville Marie building underground city to make their way to work at PVM via one of the public transit arteries that received LEED Silver EB accreditation in December 2014. converge below the property, granting access to two metro stations, two train stations, and the city’s At the base of the property, the 189,000-square-foot retail plaza grants downtown bus terminal. 1 Place Ville Marie is the centerpiece of a four-building, 3-million-square-foot access to over 75 shops and amenities providing the convenience sought development that is widely recognized as the epicentre of Montreal’s business community. by all modern-day offce workers for whom time is in short supply. The building’s 36,000-square-foot foor plates provide effciency and fexibility and can be subdivided The building’s pedestrian plaza spreads out over two acres to provide into smaller pods. Each foor is equipped with over 200 windows measuring 32.5 square feet, safe and harmonious green spaces and seating areas for quiet which food the space with natural light and provide access to the best views the city has to offer. contemplation, or for casual gatherings and team meetings. Our on-site The building’s modern comfort control systems and access to power and redundancy ensure that management team is always available to cater to any tenant need. -

Project Report

St. Felicien Cogeneration Plant Project Description and Emission Reduction Report Period Covering: January 1, 2004 through December 31, 2004 Submitted by: CHI Canada, Inc. Version 2; revised February 7, 2005 Project Description and Emission Reduction Report – January – December 2004 Page 1 of 22 Table of Contents Corresponding Corresponding EMA Description Page Workbook section* Worksheet Proponent Identification 3 Not Applicable Section 3.1 Project Description 4 Not Applicable Section 3.2 Mandatory Criteria for Registration 6 Not Applicable Section 3.3 Project Details and Other Relevant Information 6 Not Applicable Section 3.4 Emission Reduction Report 10 Section 3.5 Section 1: Biomass Destruction 10 Biomass Subsection 1: Timing 13 Timing Section 2: Steam Delivery 13 Steam Section 3: Project Emissions 16 Project Emissions Section 4: Transportation Emissions 20 Transportation Section 5: Net Emissions 21 Attachments: A: Plant Schematic B: Letter for Quebec Government C: ASTM Designation E871: Standard Method for Moisture Analysis of Particulate Wood Fuels D: Emission Reduction Workbook Undertaking 22 Section 3.6 * As outlined in the CleanAir Canada Guidance Manual for the Registration of Emission Reductions as EMA Registry Credits, effective August 23, 2004 Project Description and Emission Reduction Report – January – December 2004 Page 2 of 22 St. Felicien Cogeneration Plant Project Description and Emission Reduction Report Period Covering: January 1, 2004 through December 31, 2004 Proponent Identification 1. Proponent Company Name: CHI Canada Inc. on behalf of the St. Felicien Cogeneration Limited Partnership. 2. Contact Information: Name: Pascal J. Brun Address: CHI Canada Inc. CIBC Tower 1155 Rene-Levesque Boul. West, Suite 1715 Montreal, Quebec, Canada H3B 3Z7 Phone Number: (514) 397-0463 x224 Fax Number: (514) 397-0284 Email Address: [email protected] 3. -

The Mv Cabot and Chimo

CHAPTER 12 The m.v. Cabot and Chimo (above) each operated weekly from Montreal to St John’s THE 1960s: A NEW NAME, NEW SHIPS AND LAND TRANSPORT The 1960s would bring much change to the Clarke organization. The long-distance passenger services were coming to an end and the company was about to expand through a series of land-based acquisitions to become a nationwide transport operator, rather than the Eastern Canadian shipping company that it had been post-war. The company would have to deal with continued competition to Newfoundland and labour problems in St John's, but by doing so it would put itself in a position to be able to order two large and modern mechanized ships for what would come to be its main route between Montreal and St John's. Older ships would be sold off, others chartered and a new joint venture would be opened to serve Goose Bay and the Arctic. And as the Quebec North Shore highway system developed, the Rivière-du-Loup and Saguenay cross-river ferry operations would be renewed. As ferries replaced passenger ships and other cargo operators came onto the scene, the company would also lose some of its long-standing subsidized services. But at the same time, the scene would be set for entering the overseas trades. Peak Traffic Years In terms of ship movements, the years 1959 and 1960 were the busiest Clarke would ever see, with the company operating no fewer than 500 scheduled sailings in 1960. It also completed innumerable bulk voyages using a large number of chartered vessels. -

Conserving the Modern in Canada Buildings, Ensembles, and Sites: 1945-2005

Conserving the Modern in Canada Buildings, ensembles, and sites: 1945-2005 Conference Proceedings Trent University, Peterborough, May 6-8, 2005 Editors: Susan Algie, Winnipeg Architecture Foundation James Ashby, Docomomo Canada-Ontario Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Conserving the Modern in Canada (2005: Trent University) Conserving the Modern in Canada: buildings, ensembles, and sites, 1945-2005: conference proceedings, Trent University, Peterborough, May 6-8, 2005 / editors: Susan Algie and James Ashby. Papers presented at the Conserving the Modern in Canada conference held at Trent University, Peterborough, Ont., May 6-8, 2005. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-9683100-5-2 1. Architecture--Conservation and restoration--Canada. 2. Historic sites--Conservation and restoration--Canada. 3. Architecture--Canada--20th century. 4. Historic preservation--Canada. I. Algie, Susan, 1951 II. Ashby, James, 1962 III. Winnipeg Architecture Foundation. NA109.C3C66 2007 363.6'90971 C2007-902448-3 Also available in French. / Aussi disponible en francais. Conserving the Modern in Canada Conference Proceedings Table of Contents 1.0 Foreword . 1 2.0 Acknowledgements . 3 3.0 Conference Programme . 9 4.0 Introduction Session Papers . 15 5.0 Documentation Session Papers . 29 6.0 Evaluation Session Papers . 53 7.0 Legacy of Ronald J. Thom Session Papers . 87 8.0 Stewardship Session Papers . 113 9.0 Conservation Session Papers . 173 10.0 Education Session Papers . 203 11.0 Tours . 239 i Conserving the Modern in Canada Conference Proceedings ii Conserving the Modern in Canada Conference Proceedings FOREWORD The “Conserving the Modern in Canada” conference, held at Trent University in Peterborough from May 6 to 8, 2005, was Canada’s first national conference on the subject of the built heritage of the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s. -

Italy Creates. Gio Ponti, America and the Shaping of the Italian Design Image

Politecnico di Torino Porto Institutional Repository [Article] ITALY CREATES. GIO PONTI, AMERICA AND THE SHAPING OF THE ITALIAN DESIGN IMAGE Original Citation: Elena, Dellapiana (2018). ITALY CREATES. GIO PONTI, AMERICA AND THE SHAPING OF THE ITALIAN DESIGN IMAGE. In: RES MOBILIS, vol. 7 n. 8, pp. 20-48. - ISSN 2255-2057 Availability: This version is available at : http://porto.polito.it/2698442/ since: January 2018 Publisher: REUNIDO Terms of use: This article is made available under terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Article ("["licenses_typename_cc_by_nc_nd_30_it" not defined]") , as described at http://porto.polito. it/terms_and_conditions.html Porto, the institutional repository of the Politecnico di Torino, is provided by the University Library and the IT-Services. The aim is to enable open access to all the world. Please share with us how this access benefits you. Your story matters. (Article begins on next page) Res Mobilis Revista internacional de investigación en mobiliario y objetos decorativos Vol. 7, nº. 8, 2018 ITALY CREATES. GIO PONTI, AMERICA AND THE SHAPING OF THE ITALIAN DESIGN IMAGE ITALIA CREA. GIO PONTI, AMÉRICA Y LA CONFIGURACIÓN DE LA IMAGEN DEL DISEÑO ITALIANO Elena Dellapiana* Politecnico di Torino Abstract The paper explores transatlantic dialogues in design during the post-war period and how America looked to Italy as alternative to a mainstream modernity defined by industrial consumer capitalism. The focus begins in 1950, when the American and the Italian curated and financed exhibition Italy at Work. Her Renaissance in Design Today embarked on its three-year tour of US museums, showing objects and environments designed in Italy’s post-war reconstruction by leading architects including Carlo Mollino and Gio Ponti. -

The Watergate Project: a Contrapuntal Multi-Use Urban Complex in Washington, Dc

THE WATERGATE PROJECT: A CONTRAPUNTAL MULTI-USE URBAN COMPLEX IN WASHINGTON, DC Adrian Sheppard, FRAIC Professor of Architecture McGill University Montreal Canada INTRODUCTION Watergate is one of North America’s most imaginative and powerful architectural ensembles. Few modern projects of this scale and inventiveness have been so fittingly integrated within an existing and well-defined urban fabric without overpowering its neighbors, or creating a situation of conflict. Large contemporary urban interventions are usually conceived as objects unto themselves or as predictable replicas of their environs. There are, of course, some highly successful exceptions, such as New York’s Rockefeller Centre, which are exemplars of meaningful integration of imposing projects on an existing city, but these are rare. By today’s standards where significance in architecture is measured in terms of spectacle and flamboyance, Watergate is a dignified and rigorous urban project. Neither conventional as an urban design project, nor radical in its housing premise, it is nevertheless as provocative as anything in Europe. Because Moretti grasped the essence of Washington so accurately, he was able to bring to the city a new vision of urbanity. Watergate would prove to be an unequivocally European import grafted unto a typical North-American city, its most remarkable and successful characteristic being its relationship to its immediate context and the city in general. As an urban intervention, Watergate is an inspiring example of how a Roman architect, Luigi Moretti, succeeded in introducing a project of considerable proportions in the fabric of Washington, a city he had never visited before he received the commission. 1 Visually and symbolically, the richness of the traditional city is derived from the fact that there exists a legible distinction and balance between urban fabric and urban monument.