Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of Rock, a Monthly Magazine That Reaps the Benefits of Their Extraordinary Journalism for the Reader Decades Later, One Year at a Time

L 1 A MONTHLY TRIP THROUGH MUSIC'S GOLDEN YEARS THIS ISSUE:1969 STARRING... THE ROLLING STONES "It's going to blow your mind!" CROSBY, STILLS & NASH SIMON & GARFUNKEL THE BEATLES LED ZEPPELIN FRANK ZAPPA DAVID BOWIE THE WHO BOB DYLAN eo.ft - ink L, PLUS! LEE PERRY I B H CREE CE BEEFHE RT+NINA SIMONE 1969 No H NgWOMI WI PIK IM Melody Maker S BLAST ..'.7...,=1SUPUNIAN ION JONES ;. , ter_ Bard PUN FIRS1tintFaBil FROM 111111 TY SNOW Welcome to i AWORD MUCH in use this year is "heavy". It might apply to the weight of your take on the blues, as with Fleetwood Mac or Led Zeppelin. It might mean the originality of Jethro Tull or King Crimson. It might equally apply to an individual- to Eric Clapton, for example, The Beatles are the saints of the 1960s, and George Harrison an especially "heavy person". This year, heavy people flock together. Clapton and Steve Winwood join up in Blind Faith. Steve Marriott and Pete Frampton meet in Humble Pie. Crosby, Stills and Nash admit a new member, Neil Young. Supergroups, or more informal supersessions, serve as musical summit meetings for those who are reluctant to have theirwork tied down by the now antiquated notion of the "group". Trouble of one kind or another this year awaits the leading examples of this classic formation. Our cover stars The Rolling Stones this year part company with founder member Brian Jones. The Beatles, too, are changing - how, John Lennon wonders, can the group hope to contain three contributing writers? The Beatles diversification has become problematic. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

14302 76969 1 1>

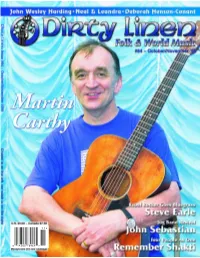

11> 0514302 76969 establishment,” he hastened to clarify. “I wish it were called the Legion of Honour, but it’s not.” Still in all, he thinks it’s good for govern- M artin C arthy ments to give cultural awards and is suitably honored by this one, which has previously gone to such outstanding folk performers as Jeannie Robertson. To decline under such circum- stances, he said, would have been “snotty.” Don’t More importantly, he conceives of his MBE as recognition he shares with the whole Call Me folk scene. “I’ve been put at the front of a very, very long queue of people who work hard to make a folk revival and a folk scene,” he said. Sir! “All those people who organized clubs for nothing and paid you out of their own pocket, and fed you and put you on the train the next morning, and put you to bed when you were drunk! What [the government is] doing, is taking notice of the fact that something’s going on for the last more than 40 years. It’s called the folk revival. They’ve ignored it for that long. And someone has suddenly taken notice, and that’s okay. A bit of profile isn’t gonna hurt us — and I say us, the plural, for the folk scene — isn’t gonna hurt us at all.” In the same year as Carthy’s moment of recognition, something happened that did hurt the folk scene. Lal Waterson, Carthy’s sister-in- law, bandmate, near neighbor and close friend, died of cancer. -

Summer 2013 and Music Club Snape and Potiphar’S Apprentices

NNootteess The Newsletter of Readifolk Issue 18 Reading's folk song Summer 2013 and music club Snape and Potiphar’s Apprentices. You can read all about these me two acts, as well as all the other artists who are appearing at Welco the club during the coming quarter, in the preview section on pages 4 and 5. to another Readifolk Do make a special note of our Grand Charity Concert on 14 newsletter July which features our very own band Rye Wolf. Rye Wolf play a mix of traditional and selfpenned songs in true folk style and Rumblings from the Roots are rapidly making a name for themselves in the local area and further afield. The concert is in support of the local community Welcome to the Summer edition of Notes. radio station, Reading4U, which is of course where many of the band performers and others from Readifolk broadcast the Once again our editor has managed to put together a weekly Readifolk Radio Show (Friday evenings 6 8 pm on newsletter packed with interesting articles and information www.reading4u.co.uk). Reading Community Radio is run which we hope you will enjoy reading. We thank all of the entirely by volunteers there are no paid employees, and it contributors to this issue of Notes for their considerable efforts. relies on donations, sponsorship etc. for its funding. We hope that with your help this concert will be able to make a sizeable As usual you will find on the back page the full programme of contribution to those funds. events at Readifolk during the next three months. -

A Folkrocker's Guide

A FOLKROCKER’S GUIDE – FOLKROCKENS FRAMVEKST 1965–1975 «The eletricifcation of all this stuf was A FOLKROCKER’S GUIDE some thing that was waiting to happen» TO THE UNIVERSE •1965–1975 – Martin Carthy «Folkrock» ble først brukt i 1965 som betegnelse på på Framveksten av folkrock i USA I Storbritania, i motsetning til i USA, kom «folkrock» til amerikanske musikere som The Byrds, den elektrifserte Bob og UK i tiåret 65–75 skapte Dylan, Simon & Garfunkel og – pussig nok – Sonny & Cher. mye av inspirasjonen for den å betegne elektrisk musikk basert på tradisjonell folke- Likevel er det i større grad møtet mellom rock og folkemusikk moderne visebølgen i Norden. musikk. i Storbritannia ca 1969–70 som ble bestemmende for hva vi Vi har bedt Morten Bing om å skrive om dette. Han er kon- på 1970-tallet kom til å legge i begrepet her hjemme. servator ved Norsk Folkemu- som hadde bakgrunn i folkrevivalen, en sanger og en felespiller – Sandy seum og var initiativtaker til men som allerede hadde forlatt Denny og Dave Swarbrick – som MORTEN BING Norges første folkrock gruppe tradisjonell folkemusikk til fordel for begge hadde bakgrunn i den Folque i 1973. egenskrevne låter. britiske folkrevivalen. Det var denne rdet «folke-rock» kombinasjonen, og resultatet, LP’n ble brukt første gang Dylan og Byrds Gruppa har sin kanskje siste På mange måter kan en si at den konsert på Rockefeller i Oslo Liege & Lief (1969), som var begyn- i Billboard 12.06.1965, engelske utviklingen gikk mot- nelsen på den britiske folkrocken. i en artikkel om Bob En viktig katalysator for framveksten 18. -

Martin Carthy Shearwater Mp3, Flac, Wma

Martin Carthy Shearwater mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: Shearwater Country: UK Released: 1972 Style: Folk MP3 version RAR size: 1865 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1296 mb WMA version RAR size: 1745 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 267 Other Formats: MP4 MMF MP1 APE MP2 AIFF VOX Tracklist A1 I Was A Young Man A2 Banks Of Green Willow A3 Handsome Polly-O A4 Outlandish Knight A5 He Called For A Candle A6 John Blunt B1 Lord Randall B2 William Taylor B3 Famous Flower Of Serving Men B4 Betsy Bell And Mary Gray Companies, etc. Printed By – E.J. Day Group Credits Arranged By, Vocals, Acoustic Guitar – Martin Carthy Art Direction, Design – David Berney Wade, Farrell Engineer – Jerry Boys Photography By – Keith Morris Producer – Terry Brown Vocals – Maddy Prior (tracks: B4) Written-By – Traditional Notes The LP includes a one-sided printed sheet with notes on all songs (probably written by Martin Carthy) and a contact print with a sequence of 14 photographs of Carthy in a studio. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Martin Shearwater (LP, CREST 008 Mooncrest CREST 008 UK 1991 Carthy Album, RE) Martin Shearwater (CD, CAS 36210-2 Castle Music CAS 36210-2 US 2005 Carthy Album) Martin Shearwater (CD, Mooncrest, TWA CRESTCD 008 CRESTCD 008 UK 1991 Carthy Album, RE) Records Martin Shearwater (CD, CMQCD1096 Castle Music CMQCD1096 UK 2005 Carthy Album, RE) Martin Shearwater (8-Trk, Y8PEG 12 PEG Y8PEG 12 UK 1972 Carthy Album) Related Music albums to Shearwater by Martin Carthy Roy Bailey - Roy Bailey Martin Carthy And Dave Swarbrick - Both Ears And The Tail Various - Classic Folk Guitar Martin Carthy - Signs Of Life Brass Monkey - The Complete Brass Monkey Spiers & Boden - The Works Ray Fisher - Traditional Songs Of Scotland Eliza Carthy - Anglicana Various - English Originals Eliza Carthy, Hannah James, Hannah Read, Hazel Askew, Jenn Butterworth, Jenny Hill , Karine Polwart, Kate Young , Mary Macmaster, Rowan Rheingans - Songs Of Separation. -

MADDY PRIOR– EFDSS Gold Badge Testimonial Maddy Prior Is Without Doubt One of the Best Known Voices from the English Folk Revi

MADDY PRIOR– EFDSS Gold Badge Testimonial Maddy Prior is without doubt one of the best known voices from the English folk revival, with a career spanning over forty years which continues today, and several key recordings which will always be identified with her, including by generations born long after the original release of those songs. Her work, however, has extended way beyond her global hits Gaudete and All Around my Hat. Born in Blackpool to Z-Cars co-creator Alan Prior, Maddy grew up in St Albans where she came to prominence in the late 1960’s in a duo with singer/ guitarist Tim Hart, who built a reputation on the folk club circuit, releasing two albums. In the early 1970’s they joined forces with Ashley Hutchings (of Fairport Convention) and Gay & Terry Woods, with the idea of fusing folk song with rock instrumentation and technique. The new group took its name from a traditional Lincolnshire ballad 'Horkstow Grange' - the tale of a character called Steeleye Span. As is well known, Steeleye Span took folk music out of the clubs and into the charts with a string of consistently strong hit albums, gold discs and world tours. Tim Hart and Maddy Prior remained the core of the group whose changing line-ups read like a Who's Who of British folk until Tim left for health reasons in 1980. Maddy continued to work with the band in its changing line-ups until 1997, when after two massive tours around the release of the album Time, she left the band after 28 years, only to return to work with them again from 2002 onwards, and is still touring with them today. -

EVERLYPEDIA (Formerly the Everly Brothers Index – TEBI) Coordinated by Robin Dunn & Chrissie Van Varik

EVERLYPEDIA (formerly The Everly Brothers Index – TEBI) Coordinated by Robin Dunn & Chrissie van Varik EVERLYPEDIA PART 2 E to J Contact us re any omissions, corrections, amendments and/or additional information at: [email protected] E______________________________________________ EARL MAY SEED COMPANY - see: MAY SEED COMPANY, EARL and also KMA EASTWOOD, CLINT – Born 31st May 1930. There is a huge quantity of information about Clint Eastwood his life and career on numerous websites, books etc. We focus mainly on his connection to The Everly Brothers and in particular to Phil Everly plus brief overview of his career. American film actor, director, producer, composer and politician. Eastwood first came to prominence as a supporting cast member in the TV series Rawhide (1959–1965). He rose to fame for playing the Man with No Name in Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy of spaghetti westerns (A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More, and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly) during the 1960s, and as San Francisco Police Department Inspector Harry Callahan in the Dirty Harry films (Dirty Harry, Magnum Force, The Enforcer, Sudden Impact and The Dead Pool) during the 1970s and 1980s. These roles, along with several others in which he plays tough-talking no-nonsense police officers, have made him an enduring cultural icon of masculinity. Eastwood won Academy Awards for Best Director and Producer of the Best Picture, as well as receiving nominations for Best Actor, for his work in the films Unforgiven (1992) and Million Dollar Baby (2004). These films in particular, as well as others including Play Misty for Me (1971), The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), Pale Rider (1985), In the Line of Fire (1993), The Bridges of Madison County (1995) and Gran Torino (2008), have all received commercial success and critical acclaim. -

Maddy Prior Silly Sisters Mp3, Flac, Wma

Maddy Prior Silly Sisters mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: Silly Sisters Country: Germany Released: 1976 Style: Folk MP3 version RAR size: 1283 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1248 mb WMA version RAR size: 1403 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 683 Other Formats: WMA MP1 VQF ADX TTA FLAC DXD Tracklist Hide Credits A1 Doffin' Mistress 2:09 A2 Burning Of Auchidoon 1:13 Lass Of Loch Royal A3 4:25 Bagpipes [Uilleann Pipes] – Gabriel McKeonGuitar – Nic Jones The Seven Joys Of Mary A4 3:16 Bassoon, Saxophone [Sopranino], Bombarde – John Gillaspie A5 My Husband's Got No Courage In Him 3:07 Singing The Travels (Symondsbury Mummers) A6 2:46 Bouzouki – Johnny MoynihanDrums [Drum] – Martin Carthy Silver Whistle A7 4:08 Whistle – Johnny Moynihan The Grey Funnel Line B1 3:03 Fiddle [5-string] – Brian GolbeyWritten-By – Cyril Tawney B2 Geordie 4:00 The Seven Wonders B3 4:31 Bombarde – John GillaspieBouzouki – Johnny MoynihanHurdy Gurdy – Andy Irvine B4 Four Loom Weaver 2:36 The Game Of Cards B5 3:16 Guitar – Nic JonesWhistle – Johnny Moynihan Dame Durdan B6 Percussion – Louis Jardin*Performer – Andy Irvine, Brian Golbey, Danny Thompson, Gabriel 2:59 McKeon, John Gillespie, Johnny Moynihan, Martin Carthy, Nic Jones, Tony Hall Credits Arranged By – June Tabor (tracks: A1 to A7, B2 to B6) Bass – Danny Thompson (tracks: A1, A3, A6 to B1, B3, B6) Design [Sleeve] – Edward Barker Engineer, Producer – Robin Black Fiddle – Nic Jones (tracks: A1, A7, B1) Guitar – Martin Carthy (tracks: A1, A6, B2, B3) Mandolin – Andy Irvine (tracks: -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1974-05-14

ride Concerning fi'ngerprint, hair samples Cowens hit from the key seconds later its largest lead t~ 43-34. Hall's attorney ob.jects to trial evidenc~ By CHUCK lji\WKINS found on the cold water faucet handle or placing Hall in Rienow Hall at any time on jury the state's case rests on "cir individual were seen by Jones getting off to the basement for cigarettes. She II8kI and tbe sink or the dormitory room where March 13. cumstantial evidence," saying that their the elevator at the fourth floor about 4 p.m. this was the last time she saw Ottens alive . ROD MAC-JOHNSON Ottens' body was fOlind . Woodward outlined to the jury the "whole case is a fingerprint and two the day of the murder. SlmpslMI lia.lel she tIIen went to Slater Starr Writers Also found on the blouse Ottens was grizzly circumstances of Ollens' death . hairs." The first witness called by the HaU to watch televilloll with ller In his opening statement preceding wearing, Woodward said, was a hair that Saying the autopsy reported death bv He said the state is fully aware of how prosecution, Brenda Simpson, AS, 612 S. boyfrleDd. George Proctor. At. now livillg testimony Monday in the James W. HaU corresponded "beyond a reasonable asphyxiation caused by strangulation, he the fingerprint on the faucet handle got Dodge St., testified she discovered the al 527 RIeDOW HaU. They retallled to murder trial, prosecutor Garl'y D. doubt" with a sample of Hall's hair. said Ottens wore only a blouse and that an there and he said tests have only shown body of Ottens sometime after 10 :30 p.m . -

Jethro Tull Discography (By Undertull)

Jethro Tull Discography (By Undertull) Jethro Tull – Discography (by Undertull) Year Album Details Pag. 1968 This Was 4 1969 Stand Up 4 1970 Benefit 5 1971 Aqualung 5 1972 Thick As A Brick 6 1972 Living In The Past 6 1973 A Passion Play 7 1974 War Child 7 1975 Minstrel In The Gallery 8 1976 M.U. - The Best Of Jethro Tull 8 1976 Too Old To Rock'N'Roll: Too Young To Die 9 1977 Songs From The Wood 9 1977 Repeat - The Best Of Jethro Tull - Vol. II 10 1978 Heavy Horses 10 1978 Live - Bursting Out 2-CD European release 11 1978 Live - Bursting Out 1 CD US release 11 1979 Stormwatch 11 1980 A 12 1982 The Broadsword And The Beast 12 1984 Under Wraps 13 1985 A Classic Case 13 1985 Original Masters 14 1987 Crest Of A Knave 14 1988 20 Years Of Jethro Tull (Box) 3-CD/ 5-LP/ 5-MC - Box 15 1988 Thick As A Brick Mobile Fidelity Gold CD 17 1988 20 Years Of Jethro Tull (Sampler) European release 17 1988 20 Years Of Jethro Tull (Sampler) US release 17 1989 Rock Island 18 1989 Stand Up Mobile Fidelity Gold CD 18 1990 Live At Hammersmith '84 19 1991 Catfish Rising 19 1992 A Little Light Music 20 1993 The Best Of Jethro Tull: The Anniversary Collection 2-CD 21 1993 25th Anniversary Box Set 4-CD Box 22 1993 Nightcap 2-CD 24 1994 Aqualung - Chrysalis 25th Anniversary Special De Luxe Edition 25 1995 Roots To Branches 25 1995 In Concert 26 1996 Aqualung - 25th Anniversary Special Edition 26 1996 The Ultimate Set 1 CD, 1 Video, 1 Book, 1 LP 27 1997 Through The Years 28 1997 Aqualung DCC Gold CD 28 1997 A Jethro Tull Collection 29 1997 Thick As A Brick - 25th Anniversary Special Edition 29 1997 The Originals: This Was/Stand Up/Benefit 3-CD 30 1997 Living In The Past Mobile Fidelity Gold 2-CD 31 1998 In Concert BBC Re-release 32 1998 A Passion Play Mobile Fidelity Gold CD 32 1998 Original Masters DCC Gold CD 33 1998 Songs From The Wood Mobile Fidelity Gold CD 33 1998 36 Greatest Hits 3-CD Box 34 2 Jethro Tull – Discography (by Undertull) Year Album Details Pag. -

Mittelalter' Im Erzählen Des Englischen Folkrock Und Wege, Sie Zu Deuten

Z i t a t i o n: Werner Bies, Die Suche nach einem „Mittelalter“ im Erzählen des englischen Folkrock und Wege, sie zu deuten, in: Mittelalter. Interdisziplinäre Forschung und Rezeptionsgeschichte, 11. Januar 2017, https://mittelalter.hypotheses.org/9450. Die Suche nach einem ‚Mittelalter’ im Erzählen des englischen Folkrock und Wege, sie zu deuten von Werner Bies An der Musik ist unter anderem reizvoll, daß sie in uns uralte Erinnerungen weckt, die oft nicht unsere eigenen, sondern Gemeingut der ganzen Menschheit sind. (Julien Green, Tagebucheintragung vom 8. März 1941).1 Szene aus dem Wandteppich "La Dame a la licorne", spaetes 15. Jh., heute im Museee de Cluny. Das Bild wurde als Cover des Folk-Albums TThe Lady and the Unicorn“ von John Renbourn verwendet. Quelle: Wikimedia Commons. Lizenz: keine (gemeinfrei). 1 Z i t a t i o n: Werner Bies, Die Suche nach einem „Mittelalter“ im Erzählen des englischen Folkrock und Wege, sie zu deuten, in: Mittelalter. Interdisziplinäre Forschung und Rezeptionsgeschichte, 11. Januar 2017, https://mittelalter.hypotheses.org/9450. 1. Definitorische Probleme 2. Räume und Orte 3. Figuren 4. Typen 5. ‚Bestiarium’ 6. Feudale Ordnungen und Tugenden 7. Christliche Frömmigkeit 8. Mittelalterliche Zeichenwelten: „le goût des énigmes“ 9. Mittelalterliche Balladen: die Stärkung des Erzählens 10. Elektrifizierung des Mittelalters, Übergänge und fusions, Bewegungen und Aufbrüche 11. Imaginationen und Konstruktionen als Überlagerungen 12. Erratisches Mittelalter statt einer Großdeutung 13. Entamerikanisierung 14. Das ‚lange Mittelalter’ vor der Industrialisierung: eine Meistererzählung? 15. Projekte einer Wiederverzauberung der Welt: Symbolwelten und Lebensstile 16. Fantasy-Literatur 17. Folkrock als Erinnerungsort für das Mittelalter? 18. Mittelalter als Imaginationen der Adoleszenz – Folkrock als Jugendliteratur? 19.