Delerium Tremens and Popular Culture In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Life of John H.W. Hawkins

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES I LIFE JOHN H. W. HAWKINS COMPILED BY HIS SON, REV. WILLIAM GEOEGE HAWKINS, A.M. "The noble self the conqueror, earnest, generous friend of the inebriate, the con- devsted advocate of the sistent, temperance reform in all its stages of development, and the kind, to aid sympathising brother, ready by voice and act every form of suffering humanity." SIXTH THOUSAND. BOSTON: PUBLISHED BY. BRIGGS AND RICHAEDS, 456 WAsnujdTn.N (-'TKI:I:T, Con. ESSEX. NEW YORK I SHELDON, HLAKKMAN & C 0. 1862. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1859, by WILLIAM GEORGE HAWKINS, In the Clerk's Office of the District Court for the District of Massachusetts. LITHOTYPED BT COWLES AND COMPANY, 17 WASHINGTON ST., BOSTON. Printed by Geo. C. Rand and Ayery. MY GRANDMOTHER, WHOSE PRAYERS, UNINTERMITTED FOR MORE THAN FORTY" YEARS, HAVE, UNDER GOD, SAVED A SON, AND GIVEN TO HER NATIVE COUNTRY A PHILANTHROPIST, WHOSE MULTIPLIED DEEDS OF LOVE ARE EVERYWHERE TO BE SEEN, AND WHICH ARE HERE BUT IMPERFECTLY RECORDED, is $0lunu IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED 550333 PREFACE. THE compiler of this volume has endeavored to " obey the command taught him in his youth, Honor thy father," etc., etc. He has, therefore, turned aside for a brief period from his professional duties, to gather up some memorials of him whose life is here but imperfectly delineated. It has indeed been a la- bor of love how and ; faithfully judiciously performed must be left for others to say. The writer has sought to avoid multiplying his own words, preferring that the subject of this memoir and his friends should tell their own story. -

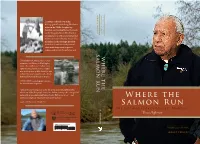

Where the Salmon Run: the Life and Legacy of Billy Frank Jr

LEGACY PROJECT A century-old feud over tribal fishing ignited brawls along Northwest rivers in the 1960s. Roughed up, belittled, and handcuffed on the banks of the Nisqually River, Billy Frank Jr. emerged as one of the most influential Indians in modern history. Inspired by his father and his heritage, the elder united rivals and survived personal trials in his long career to protect salmon and restore the environment. Courtesy Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission salmon run salmon salmon run salmon where the where the “I hope this book finds a place in every classroom and library in Washington State. The conflicts over Indian treaty rights produced a true warrior/states- man in the person of Billy Frank Jr., who endured personal tragedies and setbacks that would have destroyed most of us.” TOM KEEFE, former legislative director for Senator Warren Magnuson Courtesy Hank Adams collection “This is the fascinating story of the life of my dear friend, Billy Frank, who is one of the first people I met from Indian Country. He is recognized nationally as an outstanding Indian leader. Billy is a warrior—and continues to fight for the preservation of the salmon.” w here the Senator DANIEL K. INOUYE s almon r un heffernan the life and legacy of billy frank jr. Trova Heffernan University of Washington Press Seattle and London ISBN 978-0-295-99178-8 909 0 000 0 0 9 7 8 0 2 9 5 9 9 1 7 8 8 Courtesy Michael Harris 9 780295 991788 LEGACY PROJECT Where the Salmon Run The Life and Legacy of Billy Frank Jr. -

Nota De Prensa

Cuadrante de actividades y proyecciones para el público -XVII SICF (8-16 de noviembre de 2007)- Teatro Cervantes Salón Actos Rectorado Invitados/homenajes/galas Actividades paralelas ▲ Cine Alameda Paraninfo Presentación películas Proyecciones ► Jueves 8 Viernes 9 Sábado 10 Domingo 11 Lunes 12 Martes 13 Miércoles 14 Jueves 15 Viernes 16 + ►21:00 ▲20:30 Gala inaugural + Homenaje Concierto de BSO a cargo de la Tippi Hedren + cortos The Quiet OCUMA y la Orquesta Sinfónica y Fairy Tale y largo Mr. Brooks. Provincial de Málaga. ►16:30 ►16:30 ►16:30 ►16:30 ►16:30 ►16:30 ►16:30 The Quiet + Fairy Tale La muerte en directo (fantástico The entrance (Informativa). Cortometrajes andaluces a The last winter (Informativa). Black night (Informaiva). Película sorpresa (Premieres (cortometrajes) + Mr. Brooks €). ►18:15 Concurso*. + ►18:30 ►18:30 2007). (largometraje). ►18:45 Cecilie (Concurso). ►18:45 Cello (Concurso). Presenta Lee I’m a cyborg, but that’s OK + ►21:00 + ►18:45 Storm warning (Concurso). ►20:15 Cold prey (Concurso). Woo Chul (director). (Concurso). Gala de clausura + entrega de The 4th dimension (Concurso). ►20:30 Kilómetro 31 (Premieres 2007). ►20:30 + ►20:15 ►20:30 premios + proyección de Exiled. Presentan Tom Mattera y David La habitación de Fermat ►22:15 Rec (Premieres 2007). Kaena. The Prophecy The mad (Concurso). Mazzoni (directores). (Concurso). La antena (Concurso). ►22:30 (Homenaje a Lauren Films). ►22:15 ►20:30 + ►22:15 Wicked flowers (Concurso). Presenta Antonio Llorens The ferryman (Informativa). Rogue (Concurso). (distribuidor). Sala 1 Los pájaros (Homenaje a Tippi ►00:00 + ►22:30 Hedren). Presenta Tippi Hedren ►22:15 1408 (Premieres 2007). -

GENDERED BODIES and NERVOUS MINDS: CREATING ADDICTION in AMERICA, 1770-1910 by ELIZABETH ANN SALEM Submitted in Partial Fulfill

GENDERED BODIES AND NERVOUS MINDS: CREATING ADDICTION IN AMERICA, 1770-1910 by ELIZABETH ANN SALEM Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY August 2016 ii CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the dissertation of Elizabeth Ann Salem candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy.* Committee Chair Renée M. Sentilles Committee Member Jonathan Sadowsky Committee Member Daniel A. Cohen Committee Member Athena Vrettos Date of Defense February 29, 2016 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. iii For Richard, who believed. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vi ABSTRACT viii INTRODUCTION 10 CHAPTER ONE “Addiction” and the Nervous Body, 31 1770-1840 CHAPTER TWO “A Burden and a Curse for Life”: The Early 53 Temperance Movement Explains Addiction, 1770-1840 CHAPTER THREE “The Drunkard, Low as He is, is a Man...”: 90 Addiction during the Mid-Nineteenth Century, 1835-1860 CHAPTER FOUR “Mere Bundles of Nerves”: Opium, 122 Nervousness, and the Beginnings of Modern Addiction, 1840-1910 CONCLUSION 166 BIBLIOGRAPHY 176 v LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE 1: William Hogarth, Gin Lane (1751) 68 FIGURE 2: Nathaniel Currier and James Merritt Ives, “The 91 Drunkard’s Progress, From the First Glass to the Grave” (1846) FIGURE 3: “The Death-Bed of Madalina,” from Solon Robinson, 110 Hot Corn (1854) FIGURE 4: Depiction of a Drunkard, from Charles Jewett, 115 Temperance Toy (1840) FIGURE 5: Depiction of a Johnston, Rhode Island, fire, from 118 Charles Jewett, The Youth’s Temperance Lecturer (1841) vi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The road to a completed doctorate is often a long one, and long journeys incur multiple debts of gratitude. -

Rigorous Honesty: a Cultural History of Alcoholics Anonymous 1935-1960

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2011 Rigorous Honesty: A Cultural History of Alcoholics Anonymous 1935-1960 Kevin Kaufmann Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kaufmann, Kevin, "Rigorous Honesty: A Cultural History of Alcoholics Anonymous 1935-1960" (2011). Dissertations. 73. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/73 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2011 Kevin Kaufmann LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO RIGOROUS HONESTY: A CULTURAL HISTORY OF ALCOHOLICS ANONYMOUS 1935-1960 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN HISTORY BY KEVIN KAUFMANN CHICAGO, IL AUGUST 2011 Copyright by Kevin Kaufmann, 2011 All Rights Reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This page was about seven years in the making and I’m still concerned that I will miss someone that aided me in this process. The best way to recognize everyone is to focus on three groups of people that have been supportive, inspiring, and encouraging in all manner of ways. Of course any method of organization is bound to have its flaws and none of these groupings are exclusive. The first group is professional. I owe great thanks to my advisor and chair of my dissertation committee, Lewis Erenberg. -

Masters of Horror Vol 2 2 Bs.Indd

VERKAUF AB 23.02.2018 DREI HORROR-SPEKTAKEL JETZT IN EINER BOX! Peter Medak präsentiert: „THE WASHINGTONIANS - DIE MENSCHENFRESSER“ 3 FILME Stuart Gordon präsentiert: 1 BOX „THE BLACK CAT“ 1 PREIS Norio Tsuruta präsentiert: „DREAM CRUISE“ Titel: Masters Of Horror 2 Vol. 2 Originaltitel: Masters Of Horror 2 Vol. 2 MASTERS OF HORROR 2 VOL. 2 Prod.-Land/-jahr: USA 2007 Genre: Horror Sprachen: Deutsch/Englisch ERSTMALS Untertitel: Deutsch AUF BLU-RAY! 4 0 1 3 5 4 9 0 9 6 5 1 5 Best.-Nr.: 4013549096515 Verpackung: Softbox Laufzeit: ca. 168 Min. + Bonus Ton: DTS-HD 5.1 Bildformat: 16:9 (1,78:1) CAST MARKETING-FACTS Peter Medak präsentiert „The Washingtonians - Die Menschenfresser“: Nach dem Tod seiner Großmutter entdeckt Johnathon Schaech („The Legend of Hercules“) • Erstmals auf Blu-ray! Mike (Johnathon Schaech) hinter einem alten Gemälde eine Schriftrolle, welche die amerikanische Geschichte in einem Venus Terzo („Stephen Kings Es“) ganz anderen Licht erscheinen lässt. George Washington war ein unersättlicher, blutrünstiger Kannibale. • Gruselvergnügen x3 in einer Daniel Gillies („The Vampire Diaries“) Box! Stuart Gordon präsentiert „The Black Cat“: Basierend auf einer Erzählung von Edgar Allan Poe schuf Gruselmeister Jeffrey Combs („Beyond Re-Animator“) Stuart Gordon ein mystisches Meisterwerk, welches zwischen Realität und Fiktion, Abgrund und Liebe, Wahnsinn und • Eine Hommage an das Horror Genie wandelt. Fantastisch besetzt mit Jeffrey Combs, der die Zuschauer als Edgar Allan Poe in die tiefen Abgründe seiner CREW Genre! Fantasie entführt. -

Washingtonians.Green.09.05

1 EXT. COUNTRY ROAD - NIGHT 1 We PAN from an OWL sitting high atop a tree to... ...A PRETTY GIRL, early 20’s, walking down a lonely, moonlit country road. Carrying a knapsack. HEADLIGHTS approach from behind. She sticks her thumb out... ...and the CAR passes... ...leaving her alone again. The owl HOOTS high in the tree. The girl turns and keeps walking...until she hears something. She stops, looks over her shoulder. Sees nothing. Hears nothing. Starts walking again... ...until she hears something a second time. She glances over her shoulder again, but this time she doesn’t stop. She’s spooked. She starts to walk faster... ...and then she’s almost jogging, because whatever she hears is getting closer... She drops her knapsack, fumbles to pick it up, in a panic now...and before she can start running again... ...a RIDER ON HORSEBACK hurtles over a split-rail fence... ...we hear a CLASH OF METAL... ...and then a shiny SABER flashes in the moonlight... ...and we follow the GIRL’S SEVERED HEAD as it cartwheels through the air and lands in the middle of the country road. The BLOODY HEAD (eyes wide open) rolls to a stop and we HOLD on it for a quiet beat...then the owl HOOTS again...and we slowly PAN back to the girl’s crumpled body on the side of the road... ...where the RIDER dismounts in the background. We only see him in silhouette, framed by moonlight. And then the sound of an APPROACHING HORSE fills the night... ...and A SECOND RIDER arrives and dismounts. -

Addiction, Culture, and Narrative During the War on Drugs

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--English English 2016 The Age of Intervention: Addiction, Culture, and Narrative During the War on Drugs Ashleigh M. Hardin University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.151 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hardin, Ashleigh M., "The Age of Intervention: Addiction, Culture, and Narrative During the War on Drugs" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--English. 34. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/english_etds/34 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the English at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--English by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 473 793 CS 511 778 TITLE Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (85th, Miami, Florida, August 5-8, 2002). History Division. PUB DATE 2002-08-00 NOTE 375p.; For other sections of these proceedings, see CS 511 769-787. PUB TYPE Collected Works Proceedings (021) Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MFO1 /PC16 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Childrens Television; Females; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; Japanese; *Journalism Education; *Journalism History; Libel and Slander; Media Coverage; *Newspapers; Obscenity; Periodicals; Public Relations; Radio; Social Status; World War II IDENTIFIERS Alabama; Black Press; Brennan (William J); Douglass (Frederick); Great Britain; Japanese Relocation Camps; *Journalists; New York Times; Radical Press; Supreme Court ABSTRACT The History Division of the proceedings contains the following 13 papers: "Repositioning Radio: NBC & the 'Kitchen Radio Campaign' of 1953" (Glenda C. Williams); "The 'Poor Man's Guardian': Radicalism as a Precursor to Marxism" (Eugenie P. Almeida); "Magazine Coverage of Katharine Meyer Graham, 1963-1975" (Mary Rinkoski); "Building Resentment: How the Alabama Press Prepared the Ground for 'New York Times v. Sullivan'" (Doug Cumming); "Conjunction Junction, What Was Your Function? The Use of 'Schoolhouse Rock' to Quiet Critics of Children's Television" (David S. Silverman); "Suppression of An Enemy Language During World War II: Prohibition of the Japanese Language Speech and Expression in Japanese American Assembly Camps" (Takeya Mizuno); "The Adventures of Cuff, Massa Grub, and Dinah Snowball: Race, Ethnicity, and Gender in Frederick Douglass' Hometown Newspapers, 1847" (Frank E. Fee, Jr.); "William Brennan's Century: How a Justice Changed His Mind About Obscenity" (John M. -

The New Yorker , Published Weekly by the F - R Pub

February 28 , 1925 Price 15 cents NEW YORKER OLURD BALLOON RE . O - ( 0 U . S . Royal Cord Balloon Tires Note the Scientific Tread Design UJERE is a convincing sales point with strain and wear evenly over the entire tread 11 which the U . S . Tire Dealer is selling surface . Now note also that the tread blocks many a tire these days — are made relatively small . Visualize the action of a Balloon Tire on This is very necessary in a balloon tire . If the the road , and the science of this Royal Cord tread blocks are made larger , they throw heavy tread design immediately makes itself clear . strains on the tire . The U . S . Royal Cord Balloon Tire is built of Under load , the entire width of the tread latex - treated Web Cord - strong and flexible . is in contact with the road . So the outside It is accurately balanced . It is scientifically tread blocks have been built up to give a designed for maximum comfort , safety and ser semi - flat contour . vice life . This reduces the flexing action of the tread shoulders , distributing the United States Rubber Company TRADE TRADE MARK UNITED STATES TIRES A R E GOOD TIRES The New YorkER , published weekly by The F - R Pub . Corp . , 25 W . 45th St . , New York , N . Y . Subscription $ 5 . 00 . Vol . 1 , No . 2 . Feb . 28 , 1925 . Application for entry as second class matter pending . THE NEW YORKER Advisory Editors : Ralph Barton , Marc Connelly , Rea Irvin , George S . Kaufman , Alice Duer Miller , Dorothy Parker , Alexander Woollcott THE TALK OF THE TOWN I AST week saw Spring coquetting on Fifth Ave I hope that eventually the orderly arrangement of nue , but aside from that uncalendared escapade dining car sittings will be able to do away with the ( did you ever notice that sunny late - winter days annoying no - smoking - in - the - diner rule . -

Gallagher Dissertation

GOOD HOUSEKEEPING, GOOD HOMESTEADING: WENDELL BERRY’S DOMESTIC-PASTORAL IDEOLOGY AND LITERARY AESTHETIC by PATRICK J. GALLAGHER (Under the Direction of Major Professor Hubert McAlexander, Jr.) The adventurous and domestic muses are the warp and woof of the fabric of American culture, and these two worldviews have competed for preeminence from the beginning of American history. Being a family man and a farmer as well as a writer, it is not surprising that Wendell Berry espouses domestic ideology and sees himself as a defender of the domestic tradition in America. As such, his fiction is inspired by the domestic muse and shares similarities with the domestic-pastoral literary tradition. I begin this study by tracing the history of the domestic tradition in America from John Winthrop’s sermon “A Modell of Christian Charity” through the nineteenth-century cult of domesticity and into the twentieth century. I show that Berry’s fiction is best discussed and understood using the terms and conventions of the domestic-pastoral literary tradition: his plots are driven by concerns related to marriage, home, and farm; his characters are presented as relatively good or bad according to how well they conform to the standards of success as defined by domestic-pastoral ideology; and all of the important themes concern relationships to family members, neighbors, and home. Chapter Two shows how Berry started to idealize home and farm life in his fiction after moving back to Kentucky in the mid 1960s. The influence of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn on Berry as a writer is also discussed. Berry’s entire corpus can be seen as a response to the ideological battle between adventurousness and domesticity being played out in Twain’s masterpiece.