GENDERED BODIES and NERVOUS MINDS: CREATING ADDICTION in AMERICA, 1770-1910 by ELIZABETH ANN SALEM Submitted in Partial Fulfill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calculated for the Use of the State Of

3i'R 317.3M31 H41 A Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from University of IVIassachusetts, Boston http://www.archive.org/details/pocketalmanackfo1839amer MASSACHUSETTS REGISTER, AND mmwo states ©alrntiar, 1839. ALSO CITY OFFICERS IN BOSTON, AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. BOSTON: PUBLISHED BY JAMES LORING, 13 2 Washington Street. ECLIPSES IN 1839. 1. The first will be a great and total eclipse, on Friday March 15th, at 9h. 28m. morning, but by reason of the moon's south latitude, her shadow will not touch any part of North America. The course of the general eclipse will be from southwest to north- east, from the Pacific Ocean a little west of Chili to the Arabian Gulf and southeastern part of the Mediterranean Sea. The termination of this grand and sublime phenomenon will probably be witnessed from the summit of some of those stupendous monuments of ancient industry and folly, the vast and lofty pyramids on the banks of the Nile in lower Egypt. The principal cities and places that will be to- tally shadowed in this eclipse, are Valparaiso, Mendoza, Cordova, Assumption, St. Salvador and Pernambuco, in South America, and Sierra Leone, Teemboo, Tombucto and Fezzan, in Africa. At each of these places the duration of total darkness will be from one to six minutes, and several of the planets and fixed stars will probably be visible. 2. The other will also be a grand and beautiful eclipse, on Satur- day, September 7th, at 5h. 35m. evening, but on account of the Mnon's low latitude, and happening so late in the afternoon, no part of it will be visible in North America. -

University of Notre Dame Commencement Program

The University of Notre Dame 1978 Commencement August4 z: . The University of Notre Dame 1978 Commencement August4 Events of the Day Events of the Day Friday, August 4, 1978 BACCALAUREATE MASS 8:35 a.m. Graduates assemble in Administration Building, Main Floor, for Academic Procession to Sacred Heart Church 8:50 a.m. Academic Procession departs for Sacred Heart Church 9:00 a.m. Concelebrated Baccalaureate Mass Sacred Heart Church Principal Celebrant: Rev. Ferdinand L. Brown, C.S.C., Ph.D. Acting Provost of the Univer sity Concelebrants: Priests who will receive degrees at the August Commencement Exercises Homilist: Rev. James F. Flanigan, C.S.C., M.F.A. Chaim1an and Associate Professor of Art University of Notre Dame COM~IENCEMENT EXERCISES CONFERRING OF DEGREES 10: 20 a.m. Graduates assemble in Athletic and Convocation Center Auxiliary Gym located between Gates 1 and 2 10:50 a.m. Academic Procession begins 11 :00 a.m. Commencement Exercises- Conferring of Degrees- Athletic and Convocation Center, Concourse Commencement Address: Elizabeth A. Christman, Ph.D. Associate Professor of American Studies University of Notre Dame (Guests are requested to please be seated on the Concourse in Athletic and Convocation Center no later than 10:50 a.m.) 2 I - - EM C "' ' - f@ i · §?Ji nfM49P&&.Y 91) 8 #8 §ii@ &8 2& § 'Sttam&M· 61 5 &*·¥& &$ f*1Mi# e s- · aa *'* Baccalaure'ate Mass ,j 1 Sacred Heart Church University of Notre Dame Notre Dame, Indiana At 9 a.m. (Eastern Standard Time) Friday, August 4, 1978 Principal Celebrant: Rev. Ferdinand L. Brown, C.S.C., Acting Provost University of Notre Dame Concelebrants: Priests who will receive degrees at the August Commencement Exercises Homilist: Rev. -

Back Matter (PDF)

Do you havethese indispensable works in your referencelibrary? All priceshave been revised and most have been drastically reduced as of Octoberfirst, nineteen forty one. INDEX TO •THE AUK' The 10-YearIndex contains in onehandy volume references to all authors,localities, bird namesand publicationsreviewed that have appearedin 'The Auk' duringthe ten yearsconsidered. Subjects andtopics are indexedfully. Invaluablefor compilingthe litera- ture on any ornithologicalsubject. Volume 1 to 17, 1884-1900 Bound $3.00 Unbound $2.00 l also includesindex to the Nuttall Bulletin) Volume 18 to 27, 1901-1910 out-o/-print Unbound$2.00 Volume 28 to 37, 1911-1920 Bound $3.00 Unbound $2.00 Volume 30ø to 47, 1921-1930 Bound $3.00 Unbound $2.00 Volume 48 to 57, 1931-1940 in prepareion CHECK-LIST OF NORTH AMERICAN BIRDS Second Edition 1895 $1.00 Abridged Edition 1935 .50 (an abstracto/the 1931 Fourth Edition) The First,Third and FourthEditions are out-of-print The Fifth Editionis now beingprepared and will be published within the year CODE OF NOMENCLATURE First Edition 1892 $ .25 Revised Edition 1908 .50 FIFTY YEARS' PROGRESS IN ORNITHOLOGY. $1.00 On its fiftieth anniversaryin 1935 the Union publishedthis vol- ume of historical surveys. More facts are containedin its 200 pagesabout the marchof ornithologicalstudy in thiscountry and abroadthan in any other medium. Someof the titles: Bird Pro- tection,Photography, Economic Ornithology, Exhibition, Study Collections, etc. BO0# relatingto NATURAL HISTORY Out-of-print titles . ß . diligently sought for List issued yearly CHECK-LIST OF THE BIBLIOPHILE NORTH AMERICAN BIRDS 1836 N. HIGH STREET Abridged form o[ the out-o[-print COLUMBUS, OHIO Fourth Edition. -

Tennessee State Library and Archives Lindsley Family Genealogical

State of Tennessee Department of State Tennessee State Library and Archives Lindsley Family Genealogical Collection, 1784-2016 COLLECTION SUMMARY Creator: Rose, Stanley Frazer Inclusive Dates: 1784-2016, bulk 1850-1920 Scope & Content: Consists of genealogical research relating to the Lindsley family and its related branches. These records primarily contain photocopied research relating to the history of these families. There are two folders in Box 1 that hold information regarding Berrien family membership in the Society of the Cincinnati. Rose also compiled detailed genealogy trees and booklets for all of the family branches. This collection was kept in the original order in which it was donated. The compiler also created the folder titles. Physical Description/Extent: 6 cubic feet Accession/Record Group Number: 2016-028 Language: English Permanent Location: XV-E-5-6 1 Repository: Tennessee State Library and Archives, 403 Seventh Avenue North, Nashville, Tennessee, 37243-0312 Administrative/Biographical History Stanley Frazer Rose is a third great grandson Rev. Philip Lindsley (1786-1855). He received his law degree and master’s degree in management from Vanderbilt University. Organization/Arrangement of Materials Collection is loosely organized and retains the order in which it was received. Conditions of Access and Use Restrictions on Access: No restrictions. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction: While the Tennessee State Library and Archives houses an item, it does not necessarily hold the copyright on the item, nor may it be able to determine if the item is still protected under current copyright law. Users are solely responsible for determining the existence of such instances and for obtaining any other permissions and paying associated fees that may be necessary for the intended use. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

The Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania : an Historical Outline

WDMAN^S MEDICAL :eDtl;EGI OF PENNSYimNll^^ N,lll||»|,;,l,|l4^,.^, William ©Ecamaxx. Jr. /a1> - Purrha'^«>d for the University of Toronto Library from funds donated by Hannah Institute for the History of Medicine ^^-^^^-^^'Z^ i^^j=-<^^^^.^4^^ THE Woman's Medical College Of Pennsylvania. AN HISTORICAL OUTLINE BY CLARA MARSHALL, M.D., Dean of the College. Philadelphia : P. BLAKISTON, SON & CO., I0I2 WALNUT STREET, 1897. >.rB»^aR^ Copyright, 1897, BY P. BLAKISTON, SON & CO. TO THE ALUMN/E OF THE woman's medical college OF PENNSYLVANIA. PREFACE. T^HE following account of the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania was originally prepared with the expectation that it would constitute one of a collection of histories of the medical colleges for women in this country, which were to be embodied " in the as part of the Report on Women in Medicine United States," prepared by Dr. Frances Emily White for the World's Congress of Representative Women, held in Chicago in 1893. The delay in the publication of the large body of the reports of this Congress, promised by the United States Govern- ment, and the receipt of frequent and urgent re- the quests for more detailed information in regard to part taken by this College in the education of women in medicine, have induced the author to publish this report as a separate volume. C. M. Philadelphia^ July i, iSgf. " 'T'HE history of the movement for introducing wo- men into the full practice of the medical profes- sion is one of the most interesting of modern times. This movement has already achieved much, and far more than is often supposed. -

Chronology of the Addiction Recovery Advocacy Movement

Chronology of the Addiction Recovery Advocacy Movement Pat Taylor, Tom Hill and William White We’ve described the rich history of people in recovery, family members, friends and allies coming together to support recovery by highlighting key moments from the 1700s leading up to the present day. Please join us in acknowledging the shoulders we stand on and in forging a movement that embraces recovery as a civil right for all Americans and people all across the world. Earlier Organizing Efforts 1730s- 1830s Abstinence-based, Native American religious and cultural revitalization movements mark the first recovery focused advocacy efforts in North America. 1799 Prophet-led Recovery Movements: Handsome Lake (1799), Shawnee Prophet (Tenskwatawa, 1805), Kickapoo Prophet (Kennekuk, 1830s) 1840s The Washingtonian movement marks the first Euro-American movement organized by and for those recovering from alcoholism—a movement that involved a public pledge of sobriety and public acknowledgement of one’s recovery status. 1840s Conflict within Washingtonian societies rises over the question of legal prohibition of the sale of alcohol and the role of religion in recovery; recovering alcoholics go underground in following decades within fraternal temperance societies and ribbon reform clubs. 1845 Frederick Douglass acknowledges past intemperance, signs temperance pledge and becomes central figure in “Colored Temperance Movement”—framing sobriety as essential for full achievement of citizenship. 1895 Keeley League members (patient alumni association of the Keeley Institutes—a national network of addiction cure institutes) march on the Pennsylvania capital in support of a Keeley Law that would provide state funds for people who could not afford the Keeley cure. -

Life of John H.W. Hawkins

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES I LIFE JOHN H. W. HAWKINS COMPILED BY HIS SON, REV. WILLIAM GEOEGE HAWKINS, A.M. "The noble self the conqueror, earnest, generous friend of the inebriate, the con- devsted advocate of the sistent, temperance reform in all its stages of development, and the kind, to aid sympathising brother, ready by voice and act every form of suffering humanity." SIXTH THOUSAND. BOSTON: PUBLISHED BY. BRIGGS AND RICHAEDS, 456 WAsnujdTn.N (-'TKI:I:T, Con. ESSEX. NEW YORK I SHELDON, HLAKKMAN & C 0. 1862. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1859, by WILLIAM GEORGE HAWKINS, In the Clerk's Office of the District Court for the District of Massachusetts. LITHOTYPED BT COWLES AND COMPANY, 17 WASHINGTON ST., BOSTON. Printed by Geo. C. Rand and Ayery. MY GRANDMOTHER, WHOSE PRAYERS, UNINTERMITTED FOR MORE THAN FORTY" YEARS, HAVE, UNDER GOD, SAVED A SON, AND GIVEN TO HER NATIVE COUNTRY A PHILANTHROPIST, WHOSE MULTIPLIED DEEDS OF LOVE ARE EVERYWHERE TO BE SEEN, AND WHICH ARE HERE BUT IMPERFECTLY RECORDED, is $0lunu IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED 550333 PREFACE. THE compiler of this volume has endeavored to " obey the command taught him in his youth, Honor thy father," etc., etc. He has, therefore, turned aside for a brief period from his professional duties, to gather up some memorials of him whose life is here but imperfectly delineated. It has indeed been a la- bor of love how and ; faithfully judiciously performed must be left for others to say. The writer has sought to avoid multiplying his own words, preferring that the subject of this memoir and his friends should tell their own story. -

Temperance," in American History Through Literature, 1820- 1870

Claybaugh, Amanda. "Temperance," in American History Through Literature, 1820- 1870. Eds. Janet Gabler-Hover and Robert Sattlemeyer. Detroit: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2006, 1152-58. TEMPERANCE The antebellum period was famously a time of social reform Reformers agitated for the abolition of slavery and the expansion of women's rights, but they also renovated prisons and poorhouses and instituted mental asylums and schools for the deaf and the blind. They passed out religious tracts and insisted that the Sabbath be observed. They improved sewers and drains, inspected the homes of the poor, and cam- paigned against the death penalty and for world peace. They lived in communes, rejected fashion in favor of rational dress, and took all sorts of water cures. But above all else, they advocated temperance reform. Antebellum temperance reform was the largest mass . movement in United States history—and certainly one i of the most influential. Temperance reform unfolded in five sometimes ; ovei l a p p i n g phases: (1) the licensing movement of the , eighteenth century, (2) the moderationist societies of the early nineteenth century, (3) the temperance soci- f eties of the early to mid-nineteenth century, (4) the teetotal societies of the mid-nineteenth century, and (5) the prohibitionist movement of the mid-nine- teenth century. The essay that follows will sketch out "•' the history of temperance reform, pausing to consider -, four milestone temperance texts, and will conclude by discussing the effects that temperance reform had on the non-canonical and canonical literary texts of the antebellum period. H I THROUGH LITERATURE, 1820-187 0 A>1 TEMPERANCE THE PREHISTORY OF TEMPERANCE Mather is anticipating the form that temperance activ- REFORM: LICENSING ity would take throughout the eighteenth century, Throughout the seventeenth century and much of the when the so-called licensing movement would seek to eighteenth, drinking was frequent and alcohol was abun- ensure that drinking houses and the drink trade re- dant. -

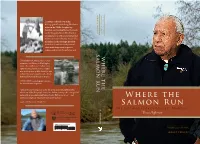

Where the Salmon Run: the Life and Legacy of Billy Frank Jr

LEGACY PROJECT A century-old feud over tribal fishing ignited brawls along Northwest rivers in the 1960s. Roughed up, belittled, and handcuffed on the banks of the Nisqually River, Billy Frank Jr. emerged as one of the most influential Indians in modern history. Inspired by his father and his heritage, the elder united rivals and survived personal trials in his long career to protect salmon and restore the environment. Courtesy Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission salmon run salmon salmon run salmon where the where the “I hope this book finds a place in every classroom and library in Washington State. The conflicts over Indian treaty rights produced a true warrior/states- man in the person of Billy Frank Jr., who endured personal tragedies and setbacks that would have destroyed most of us.” TOM KEEFE, former legislative director for Senator Warren Magnuson Courtesy Hank Adams collection “This is the fascinating story of the life of my dear friend, Billy Frank, who is one of the first people I met from Indian Country. He is recognized nationally as an outstanding Indian leader. Billy is a warrior—and continues to fight for the preservation of the salmon.” w here the Senator DANIEL K. INOUYE s almon r un heffernan the life and legacy of billy frank jr. Trova Heffernan University of Washington Press Seattle and London ISBN 978-0-295-99178-8 909 0 000 0 0 9 7 8 0 2 9 5 9 9 1 7 8 8 Courtesy Michael Harris 9 780295 991788 LEGACY PROJECT Where the Salmon Run The Life and Legacy of Billy Frank Jr. -

Nota De Prensa

Cuadrante de actividades y proyecciones para el público -XVII SICF (8-16 de noviembre de 2007)- Teatro Cervantes Salón Actos Rectorado Invitados/homenajes/galas Actividades paralelas ▲ Cine Alameda Paraninfo Presentación películas Proyecciones ► Jueves 8 Viernes 9 Sábado 10 Domingo 11 Lunes 12 Martes 13 Miércoles 14 Jueves 15 Viernes 16 + ►21:00 ▲20:30 Gala inaugural + Homenaje Concierto de BSO a cargo de la Tippi Hedren + cortos The Quiet OCUMA y la Orquesta Sinfónica y Fairy Tale y largo Mr. Brooks. Provincial de Málaga. ►16:30 ►16:30 ►16:30 ►16:30 ►16:30 ►16:30 ►16:30 The Quiet + Fairy Tale La muerte en directo (fantástico The entrance (Informativa). Cortometrajes andaluces a The last winter (Informativa). Black night (Informaiva). Película sorpresa (Premieres (cortometrajes) + Mr. Brooks €). ►18:15 Concurso*. + ►18:30 ►18:30 2007). (largometraje). ►18:45 Cecilie (Concurso). ►18:45 Cello (Concurso). Presenta Lee I’m a cyborg, but that’s OK + ►21:00 + ►18:45 Storm warning (Concurso). ►20:15 Cold prey (Concurso). Woo Chul (director). (Concurso). Gala de clausura + entrega de The 4th dimension (Concurso). ►20:30 Kilómetro 31 (Premieres 2007). ►20:30 + ►20:15 ►20:30 premios + proyección de Exiled. Presentan Tom Mattera y David La habitación de Fermat ►22:15 Rec (Premieres 2007). Kaena. The Prophecy The mad (Concurso). Mazzoni (directores). (Concurso). La antena (Concurso). ►22:30 (Homenaje a Lauren Films). ►22:15 ►20:30 + ►22:15 Wicked flowers (Concurso). Presenta Antonio Llorens The ferryman (Informativa). Rogue (Concurso). (distribuidor). Sala 1 Los pájaros (Homenaje a Tippi ►00:00 + ►22:30 Hedren). Presenta Tippi Hedren ►22:15 1408 (Premieres 2007). -

The Ancestry of James Patten

THE ANCESTRY OF JAMES PATTEN THE ANCESTRY OF JAMES PATTEN 1747?-1817 OF ARUNDEL (KENNEBUNKPORT) MAINE BY WALTER GOODWIN DA VIS PORTLAND, MAINE THE SOUTHWORTH-.ANTHOENSEN PRESS 1941 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Vil I. MATTHEW PATTEN OF BIDDEFORD 1 II. HECTOR p A TTEN OF SACO 11 III. WILLIAM PATTEN OF Bosnrn 43 IV. RonERT PATTEN oF ARUNDEL HJ V. WILLIAM PATTEN 01<' WELLS ,·0 VI. JOHNSTON OF STROUDWATER. 89 INDEX 105 INTRODUCTION 'I'HE title of this pamphlet, The Ancestry of James Patten, is to a great extent deceptive, for on the paternal side James Patten's father is his only "ancestor" now, or likely to be, discovered, while on the maternal side we can trace a slight three generations to a shadowy great-grandfather. However, the pamphlet is the sev enth in a series dealing with the ancestry of my great-great grandparents, and for the sake of uniformity it is so entitled. Actually it deals with the descendants of six men who emigrated to New England in the early years of the eighteenth century, four of them being the brothers Matthew Patten of Biddeford, Hector Patten of Saco, Robert Patten of Arundel, and '\Villiam Patten of Boston. The fifth, ·william Patten of Wells, presumably a close kinsman of the brothers, is included as by so doing all of the Pat ten emigrants who settled in Maine are conveniently grouped in one volume, while the sixth, James Johnston, finds an appropriate place herein as his granddaughter was James Patten's mother. All of these men were of Scotch descent, springing from fami lies which left Scotland in the seventeenth century, encouraged by the British government, to settle in the northern counties of Ireland which formed the ancient kingdom of Ulster, where they became a tough and unwelcome minority.