Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pulitzer Prizes for International Reporting in the Third Phase of Their Development, 1963-1977

INTRODUCTION THE PULITZER PRIZES FOR INTERNATIONAL REPORTING IN THE THIRD PHASE OF THEIR DEVELOPMENT, 1963-1977 Heinz-Dietrich Fischer The rivalry between the U.S.A. and the U.S.S.R. having shifted, in part, to predomi- nance in the fields of space-travel and satellites in the upcoming space age, thus opening a new dimension in the Cold War,1 there were still existing other controversial issues in policy and journalism. "While the colorful space competition held the forefront of public atten- tion," Hohenberg remarks, "the trained diplomatic correspondents of the major newspa- pers and wire services in the West carried on almost alone the difficult and unpopular East- West negotiations to achieve atomic control and regulation and reduction of armaments. The public seemed to want to ignore the hard fact that rockets capable of boosting people into orbit for prolonged periods could also deliver atomic warheads to any part of the earth. It continued, therefore, to be the task of the responsible press to assign competent and highly trained correspondents to this forbidding subject. They did not have the glamor of TV or the excitement of a space shot to focus public attention on their work. Theirs was the responsibility of obliging editors to publish material that was complicated and not at all easy for an indifferent public to grasp. It had to be done by abandoning the familiar cliches of journalism in favor of the care and the art of the superior historian .. On such an assignment, no correspondent was a 'foreign' correspondent. The term was outdated. -

The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes Michael A

Brooklyn Law Review Volume 71 | Issue 4 Article 1 2006 It's Not About the Money: The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes Michael A. McCann Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr Recommended Citation Michael A. McCann, It's Not About the Money: The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes, 71 Brook. L. Rev. (2006). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr/vol71/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Law Review by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. ARTICLES It’s Not About the Money: THE ROLE OF PREFERENCES, COGNITIVE BIASES, AND HEURISTICS AMONG PROFESSIONAL ATHLETES Michael A. McCann† I. INTRODUCTION Professional athletes are often regarded as selfish, greedy, and out-of-touch with regular people. They hire agents who are vilified for negotiating employment contracts that occasionally yield compensation in excess of national gross domestic products.1 Professional athletes are thus commonly assumed to most value economic remuneration, rather than the “love of the game” or some other intangible, romanticized inclination. Lending credibility to this intuition is the rational actor model; a law and economic precept which presupposes that when individuals are presented with a set of choices, they rationally weigh costs and benefits, and select the course of † Assistant Professor of Law, Mississippi College School of Law; LL.M., Harvard Law School; J.D., University of Virginia School of Law; B.A., Georgetown University. Prior to becoming a law professor, the author was a Visiting Scholar/Researcher at Harvard Law School and a member of the legal team for former Ohio State football player Maurice Clarett in his lawsuit against the National Football League and its age limit (Clarett v. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

A Giant Whiff: Why the New CBA Fails Baseball's Smartest Small Market Franchises

DePaul Journal of Sports Law Volume 4 Issue 1 Summer 2007: Symposium - Regulation of Coaches' and Athletes' Behavior and Related Article 3 Contemporary Considerations A Giant Whiff: Why the New CBA Fails Baseball's Smartest Small Market Franchises Jon Berkon Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jslcp Recommended Citation Jon Berkon, A Giant Whiff: Why the New CBA Fails Baseball's Smartest Small Market Franchises, 4 DePaul J. Sports L. & Contemp. Probs. 9 (2007) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jslcp/vol4/iss1/3 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Sports Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A GIANT WHIFF: WHY THE NEW CBA FAILS BASEBALL'S SMARTEST SMALL MARKET FRANCHISES INTRODUCTION Just before Game 3 of the World Series, viewers saw something en- tirely unexpected. No, it wasn't the sight of the Cardinals and Tigers playing baseball in late October. Instead, it was Commissioner Bud Selig and Donald Fehr, the head of Major League Baseball Players' Association (MLBPA), gleefully announcing a new Collective Bar- gaining Agreement (CBA), thereby guaranteeing labor peace through 2011.1 The deal was struck a full two months before the 2002 CBA had expired, an occurrence once thought as likely as George Bush and Nancy Pelosi campaigning for each other in an election year.2 Baseball insiders attributed the deal to the sport's economic health. -

Life of John H.W. Hawkins

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES I LIFE JOHN H. W. HAWKINS COMPILED BY HIS SON, REV. WILLIAM GEOEGE HAWKINS, A.M. "The noble self the conqueror, earnest, generous friend of the inebriate, the con- devsted advocate of the sistent, temperance reform in all its stages of development, and the kind, to aid sympathising brother, ready by voice and act every form of suffering humanity." SIXTH THOUSAND. BOSTON: PUBLISHED BY. BRIGGS AND RICHAEDS, 456 WAsnujdTn.N (-'TKI:I:T, Con. ESSEX. NEW YORK I SHELDON, HLAKKMAN & C 0. 1862. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1859, by WILLIAM GEORGE HAWKINS, In the Clerk's Office of the District Court for the District of Massachusetts. LITHOTYPED BT COWLES AND COMPANY, 17 WASHINGTON ST., BOSTON. Printed by Geo. C. Rand and Ayery. MY GRANDMOTHER, WHOSE PRAYERS, UNINTERMITTED FOR MORE THAN FORTY" YEARS, HAVE, UNDER GOD, SAVED A SON, AND GIVEN TO HER NATIVE COUNTRY A PHILANTHROPIST, WHOSE MULTIPLIED DEEDS OF LOVE ARE EVERYWHERE TO BE SEEN, AND WHICH ARE HERE BUT IMPERFECTLY RECORDED, is $0lunu IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED 550333 PREFACE. THE compiler of this volume has endeavored to " obey the command taught him in his youth, Honor thy father," etc., etc. He has, therefore, turned aside for a brief period from his professional duties, to gather up some memorials of him whose life is here but imperfectly delineated. It has indeed been a la- bor of love how and ; faithfully judiciously performed must be left for others to say. The writer has sought to avoid multiplying his own words, preferring that the subject of this memoir and his friends should tell their own story. -

THE RISE of the FOURTH REICH Escape the Disgrace of Deposition Or Capitulation—Choose Death.” He Or- Dered That Their Bodies Be Burned Immediately

T H E S EC R ET SO C I ET I E S T H AT TH RE AT EN TO TAK E OV ER AMER I C A JIM MARRS This book is dedicated to my father, my uncles, and all the Allied soldiers who sacrificed so willingly to serve their country in World War II. They deserve better. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 The Escape of Adolf Hitler 2 A Definition of Terms 5 Communism versus National Socialism 8 PART ONE THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF THE THIRD REICH 1. A New Reich Begins 19 2. The Strange Case of Rudolf Hess 36 3. Nazi Wonder Weapons 50 4. A Treasure Trove 92 5. The Writing on the Wall 106 PART TWO THE REICH CONSOLIDATES 6. The Ratlines 125 7. Project Paperclip and the Space Race 149 8. Nazi Mind Control 178 vi CONTENTS 9. Business as Usual 204 10. Kennedy and the Nazis 220 PART THREE THE REICH ASCENDANT 11. Rebuilding the Reich, American-Style 235 12. Guns, Drugs, and Eugenics 262 13. Religion 286 14. Education 296 15. Psychology and Public Control 321 16. Propaganda 343 EPILOGUE 361 SOURCES 377 INDEX 413 Acknowledgments About the Author Other Books by Jim Marrs Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher INTRODUCTION ADOLF HIT LER’S THI R D REICH EN DED I N BER LI N ON APR I L 30, 1945. Thunder reverberated from a storm of Rus sian artillery that was bom- barding the ruined capital. The day before, along with the incoming shells, came particularly bad news for the fuehrer, who by this late date in World War II was confined to his underground bunker beneath the Reich chan- cellery. -

The Changing Face of Baseball: in an Age of Globalization, Is Baseball Still As American As Apple Pie and Chevrolet?

University of Miami International and Comparative Law Review Volume 8 Issue 1 Article 4 1-1-2000 The Changing Face Of Baseball: In An Age Of Globalization, Is Baseball Still As American As Apple Pie And Chevrolet? Jason S. Weiss Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umiclr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Jason S. Weiss, The Changing Face Of Baseball: In An Age Of Globalization, Is Baseball Still As American As Apple Pie And Chevrolet?, 8 U. Miami Int’l & Comp. L. Rev. 123 (2000) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umiclr/vol8/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CHANGING FACE OF BASEBALL: IN AN AGE OF GLOBALIZATION, IS BASEBALL STILL AS AMERICAN AS APPLE PIE AND CHEVROLET?* JASON S. WEISS** I. INTRODUCTION II. THE MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL DRAFT AND HOW IT WORKS III. THE HANDLING OF THE FIRST CUBAN DEFECTOR IN MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL IV. THE CURRENT PROCEDURE FOR CUBAN PLAYERS TO ENTER THE UNITED STATES AND JOIN MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL V. EXAMPLES OF HOW THE LOOPHOLE HAS WORKED VI. THE DISCOVERY AND EXPLOITATION OF MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL'S LOOPHOLE VI. WHAT FUTURE LIES AHEAD FOR CUBANS WHO WANT TO ENTER THE UNITED STATES TO PLAY MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL? VIII. -

The Disparate Treatment of Latin American Baseball Players in Major League Baseball

University of St. Thomas Journal of Law and Public Policy Volume 2 Issue 1 Spring 2008 Article 4 January 2008 El Monticulo ("The Mound"): The Disparate Treatment of Latin American Baseball Players in Major League Baseball Jeffrey S. Storms Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/ustjlpp Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey S. Storms, El Monticulo ("The Mound"): The Disparate Treatment of Latin American Baseball Players in Major League Baseball, 2 U. ST. THOMAS J.L. & PUB. POL'Y 81 (2008). Available at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/ustjlpp/vol2/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UST Research Online and the University of St. Thomas Journal of Law and Public Policy. For more information, please contact the Editor-in-Chief at [email protected]. No. 1] El Monticulo ("The Mound') 81 EL MONTiCULO ("THE MOUND"): THE DISPARATE TREATMENT OF LATIN AMERICAN BASEBALL PLAYERS IN MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL JEFFREY S. STORMS* I. INTRODUCTION While baseball is commonly recognized as the great American pastime, the game is undeniably becoming a global pursuit.' In fact, as of the 2002 season, over one quarter of the players in Major League Baseball ("MLB") were born outside of the United States.2 Latin American ballplayers, in particular, have long contributed to baseball's deep and rich history, and today occupy a substantial portion of MLB rosters.' Major League Baseball recently recognized this long standing contribution by naming a Latin American Legends team.4 In announcing the Legends team, MLB *Jeff Storms is an associate at the Minneapolis law firm of Flynn, Gaskins & Bennett LLP; J.D., University of St. -

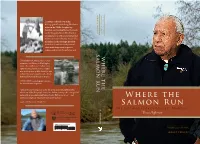

Where the Salmon Run: the Life and Legacy of Billy Frank Jr

LEGACY PROJECT A century-old feud over tribal fishing ignited brawls along Northwest rivers in the 1960s. Roughed up, belittled, and handcuffed on the banks of the Nisqually River, Billy Frank Jr. emerged as one of the most influential Indians in modern history. Inspired by his father and his heritage, the elder united rivals and survived personal trials in his long career to protect salmon and restore the environment. Courtesy Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission salmon run salmon salmon run salmon where the where the “I hope this book finds a place in every classroom and library in Washington State. The conflicts over Indian treaty rights produced a true warrior/states- man in the person of Billy Frank Jr., who endured personal tragedies and setbacks that would have destroyed most of us.” TOM KEEFE, former legislative director for Senator Warren Magnuson Courtesy Hank Adams collection “This is the fascinating story of the life of my dear friend, Billy Frank, who is one of the first people I met from Indian Country. He is recognized nationally as an outstanding Indian leader. Billy is a warrior—and continues to fight for the preservation of the salmon.” w here the Senator DANIEL K. INOUYE s almon r un heffernan the life and legacy of billy frank jr. Trova Heffernan University of Washington Press Seattle and London ISBN 978-0-295-99178-8 909 0 000 0 0 9 7 8 0 2 9 5 9 9 1 7 8 8 Courtesy Michael Harris 9 780295 991788 LEGACY PROJECT Where the Salmon Run The Life and Legacy of Billy Frank Jr. -

Nota De Prensa

Cuadrante de actividades y proyecciones para el público -XVII SICF (8-16 de noviembre de 2007)- Teatro Cervantes Salón Actos Rectorado Invitados/homenajes/galas Actividades paralelas ▲ Cine Alameda Paraninfo Presentación películas Proyecciones ► Jueves 8 Viernes 9 Sábado 10 Domingo 11 Lunes 12 Martes 13 Miércoles 14 Jueves 15 Viernes 16 + ►21:00 ▲20:30 Gala inaugural + Homenaje Concierto de BSO a cargo de la Tippi Hedren + cortos The Quiet OCUMA y la Orquesta Sinfónica y Fairy Tale y largo Mr. Brooks. Provincial de Málaga. ►16:30 ►16:30 ►16:30 ►16:30 ►16:30 ►16:30 ►16:30 The Quiet + Fairy Tale La muerte en directo (fantástico The entrance (Informativa). Cortometrajes andaluces a The last winter (Informativa). Black night (Informaiva). Película sorpresa (Premieres (cortometrajes) + Mr. Brooks €). ►18:15 Concurso*. + ►18:30 ►18:30 2007). (largometraje). ►18:45 Cecilie (Concurso). ►18:45 Cello (Concurso). Presenta Lee I’m a cyborg, but that’s OK + ►21:00 + ►18:45 Storm warning (Concurso). ►20:15 Cold prey (Concurso). Woo Chul (director). (Concurso). Gala de clausura + entrega de The 4th dimension (Concurso). ►20:30 Kilómetro 31 (Premieres 2007). ►20:30 + ►20:15 ►20:30 premios + proyección de Exiled. Presentan Tom Mattera y David La habitación de Fermat ►22:15 Rec (Premieres 2007). Kaena. The Prophecy The mad (Concurso). Mazzoni (directores). (Concurso). La antena (Concurso). ►22:30 (Homenaje a Lauren Films). ►22:15 ►20:30 + ►22:15 Wicked flowers (Concurso). Presenta Antonio Llorens The ferryman (Informativa). Rogue (Concurso). (distribuidor). Sala 1 Los pájaros (Homenaje a Tippi ►00:00 + ►22:30 Hedren). Presenta Tippi Hedren ►22:15 1408 (Premieres 2007). -

The Effects of Collective Bargaining on Minor League Baseball Players

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLS\4-1\HLS102.txt unknown Seq: 1 14-MAY-13 15:57 Touching Baseball’s Untouchables: The Effects of Collective Bargaining on Minor League Baseball Players Garrett R. Broshuis* Abstract Collective bargaining has significantly altered the landscape of labor relations in organized baseball. While its impact on the life of the major league player has garnered much discussion, its impact on the majority of professional baseball players—those toiling in the minor leagues—has re- ceived scant attention. Yet an examination of every collective bargaining agreement between players and owners since the original 1968 Basic Agree- ment reveals that collective bargaining has greatly impacted minor league players, even though the Major League Baseball Players Association does not represent them. While a few of the effects of collective bargaining on the minor league player have been positive, the last two agreements have estab- lished a dangerous trend in which the Players Association consciously con- cedes an issue with negative implications for minor leaguers in order to receive something positive for major leaguers. Armed with a court-awarded antitrust exemption solidified by legisla- tion, Major League Baseball has continually and systematically exploited mi- * Prior to law school, the author played six years as a pitcher in the San Francisco Giants’ minor league system and wrote about life in the minors for The Sporting News and Baseball America. He has represented players as an agent and is a J.D. Candidate, 2013, at Saint Louis University School of Law. The author would like to thank Professor Susan A. FitzGibbon, Director, William C.