Striking out Competitive Balance in Sports, Antitrust, and Intellectual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record—Senate S13621

November 2, 1999 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð SENATE S13621 message from the Chicago Bears. Many ex- with him. You could tell he was very The last point I will make is, toward ecutives knew what it said before they read genuine.'' the end of his life when announcing he it: Walter Payton, one of the best ever to Bears fans in Chicago felt the same way, faced this fatal illness, he made a plea which is why reaction to his death was swift play running back, had died. across America to take organ donation For the past several days it has been ru- and universal. mored that Payton had taken a turn for the ``He to me is ranked with Joe DiMaggio in seriously. He needed a liver transplant worse, so the league was braced for the news. baseballÐhe was the epitome of class,'' said at one point in his recuperation. It Still, the announcement that Payton had Hank Oettinger, a native of Chicago who was could have made a difference. It did not succumbed to bile-duct cancer at 45 rocked watching coverage of Payton's death at a bar happen. and deeply saddened the world of profes- on the city's North Side. ``The man was such I do not know the medical details as sional football. a gentleman, and he would show it on the to his passing, but Walter Payton's ``His attitude for life, you wanted to be football field.'' message in his final months is one we around him,'' said Mike Singletary, a close Several fans broke down crying yesterday as they called into Chicago television sports should take to heart as we remember friend who played with Payton from 1981 to him, not just from those fuzzy clips of 1987 on the Bears. -

LANSING UNITED LANSING Unitedvs. Fort Pitt Regiment

LANSING UNITED 2014 MIDWEST REGION CHAMPIONS P.O. BOX 246 • HOLT, MI 48842 PHONE: (517) 812-0628 • WWW.LANUNITED.COM 20142015 SCHEDULE & RESULTS LANSING UNITED vs. Fort Pitt Regiment APRIL Match 9 • June 5, 2015 • 7 p.m. • East Lansing Soccer Complex • East Lansing, Mich. MAY Fri. 24 Northwood University [1] .......... L, 0-1 Fri. 2 Ann Arbor Football Club # ........ 5 p.m. LAST MATCH Wed. 7 @ Michigan Bucks # .....................TBA MAY Taking on in-state rival Detroit City FC at MSU’s DeMartin Stadium, Tue. 13 Ann Arbor Football Club # ........ 1 p.m. Sat. 2 AFC Ann Arbor [1] .....................W, 3-0 Fri. 16 Westfield Select * ..................... 7 p.m. Lansing United came out on top in a convincing 3-1 win. The victory Sat. 9 Grand Rapids FC [1] ................... L, 0-1 Sun. 18 Michigan Stars * ....................... 7 p.m. moved the club to a 2-0-1 record. United was strong from the first Wed. 13 RWB Adria [2] ................... D, 0-0 (4-2) Fri. 23 @ Detroit City FC * .............. 7:30 p.m. Wed. 20 Louisville City FC [2] ................... L, 0-1 whistle and won the possession battle, 57 percent to 43 percent. Sat. 31 @ Erie Admirals ........................ 7 p.m. Fri. 22 Indiana Fire * .............................D, 0-0 Stephen Owusu’s 13th minute goal put United ahead, and second half Sun. 24 @ Michigan Stars * ..................W, 0-1 subs Jason Stacy and Matt Rickard found the back of the net to give the JUNE Sun. 31 Detroit City FC * [3] ..................W, 3-1 Sun. 1 @ Fort Pitt Regiment ................ 2 p.m. club the win. -

The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes Michael A

Brooklyn Law Review Volume 71 | Issue 4 Article 1 2006 It's Not About the Money: The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes Michael A. McCann Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr Recommended Citation Michael A. McCann, It's Not About the Money: The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes, 71 Brook. L. Rev. (2006). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr/vol71/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Law Review by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. ARTICLES It’s Not About the Money: THE ROLE OF PREFERENCES, COGNITIVE BIASES, AND HEURISTICS AMONG PROFESSIONAL ATHLETES Michael A. McCann† I. INTRODUCTION Professional athletes are often regarded as selfish, greedy, and out-of-touch with regular people. They hire agents who are vilified for negotiating employment contracts that occasionally yield compensation in excess of national gross domestic products.1 Professional athletes are thus commonly assumed to most value economic remuneration, rather than the “love of the game” or some other intangible, romanticized inclination. Lending credibility to this intuition is the rational actor model; a law and economic precept which presupposes that when individuals are presented with a set of choices, they rationally weigh costs and benefits, and select the course of † Assistant Professor of Law, Mississippi College School of Law; LL.M., Harvard Law School; J.D., University of Virginia School of Law; B.A., Georgetown University. Prior to becoming a law professor, the author was a Visiting Scholar/Researcher at Harvard Law School and a member of the legal team for former Ohio State football player Maurice Clarett in his lawsuit against the National Football League and its age limit (Clarett v. -

Statista European Football Benchmark 2018 Questionnaire – July 2018

Statista European Football Benchmark 2018 Questionnaire – July 2018 How old are you? - _____ years Age, categorial - under 18 years - 18 - 24 years - 25 - 34 years - 35 - 44 years - 45 - 54 years - 55 - 64 years - 65 and older What is your gender? - female - male Where do you currently live? - East Midlands, England - South East, England - East of England - South West, England - London, England - Wales - North East, England - West Midlands, England - North West, England - Yorkshire and the Humber, England - Northern Ireland - I don't reside in England - Scotland And where is your place of birth? - East Midlands, England - South East, England - East of England - South West, England - London, England - Wales - North East, England - West Midlands, England - North West, England - Yorkshire and the Humber, England - Northern Ireland - My place of birth is not in England - Scotland Statista Johannes-Brahms-Platz 1 20355 Hamburg Tel. +49 40 284 841-0 Fax +49 40 284 841-999 [email protected] www.statista.com Statista Survey - Questionnaire –17.07.2018 Screener Which of these topics are you interested in? - football - painting - DIY work - barbecue - cooking - quiz shows - rock music - environmental protection - none of the above Interest in clubs (1. League of the respective country) Which of the following Premier League clubs are you interested in (e.g. results, transfers, news)? - AFC Bournemouth - Huddersfield Town - Brighton & Hove Albion - Leicester City - Cardiff City - Manchester City - Crystal Palace - Manchester United - Arsenal F.C. - Newcastle United - Burnley F.C. - Stoke City - Chelsea F.C. - Swansea City - Everton F.C. - Tottenham Hotspur - Fulham F.C. - West Bromwich Albion - Liverpool F.C. -

"The Olympics Don't Take American Express"

“…..and the Olympics didn’t take American Express” Chapter One: How ‘Bout Those Cowboys I inherited a predisposition for pain from my father, Ron, a born and raised Buffalonian with a self- mutilating love for the Buffalo Bills. As a young boy, he kept scrap books of the All American Football Conference’s original Bills franchise. In the 1950s, when the AAFC became the National Football League and took only the Cleveland Browns, San Francisco 49ers, and Baltimore Colts with it, my father held out for his team. In 1959, when my father moved the family across the country to San Jose, California, Ralph Wilson restarted the franchise and brought Bills’ fans dreams to life. In 1960, during the Bills’ inaugural season, my father resumed his role as diehard fan, and I joined the ranks. It’s all my father’s fault. My father was the one who tapped his childhood buddy Larry Felser, a writer for the Buffalo Evening News, for tickets. My father was the one who took me to Frank Youell Field every year to watch the Bills play the Oakland Raiders, compliments of Larry. By the time I had celebrated Cookie Gilcrest’s yardage gains, cheered Joe Ferguson’s arm, marveled over a kid called Juice, adapted to Jim Kelly’s K-Gun offense, got shocked by Thurman Thomas’ receptions, felt the thrill of victory with Kemp and Golden Wheels Dubenion, and suffered the agony of defeat through four straight Super Bowls, I was a diehard Bills fan. Along with an entourage of up to 30 family and friends, I witnessed every Super Bowl loss. -

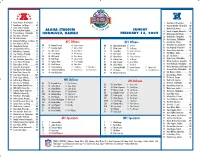

NFC Defense ALOHA STADIUM HONOLULU, HAWAII AFC Offense

4 Adam Vinatieri, New England. K 2 David Akers, Philadelphia. K 9 Drew Brees, San Diego . QB 5 Donovan McNabb, Philadelphia . QB 9 Shane Lechler, Oakland . P 7 Michael Vick, Atlanta . QB 12 Tom Brady, New England. QB ALOHA STADIUM SUNDAY 11 Daunte Culpepper, Minnesota. QB 18 Peyton Manning, Indianapolis . QB HONOLULU, HAWAII FEBRUARY 13, 2005 17 Mitch Berger, New Orleans . P 20 Tory James, Cincinnati . CB 20 Ronde Barber, Tampa Bay . CB 20 Ed Reed, Baltimore . SS 20 Brian Dawkins, Philadelphia . FS 21 LaDainian Tomlinson, San Diego . RB AFC Offense 20 Allen Rossum, Atlanta. KR 22 Nate Clements, Buffalo . CB NFC Offense 21 Tiki Barber, New York Giants . RB 24 Champ Bailey, Denver . CB WR 88 Marvin Harrison 80 Andre Johnson WR 87 Muhsin Muhammad 87 Joe Horn 26 Lito Sheppard, Philadelphia . CB 24 Terrence McGee, Buffalo . CB LT 75 Jonathan Ogden 77 Marvel Smith LT 71 Walter Jones 72 Tra Thomas 30 Ahman Green, Green Bay. RB 32 Rudi Johnson, Cincinnati . RB LG 66 Alan Faneca 54 Brian Waters LG 73 Larry Allen 76 Steve Hutchinson 43 Troy Polamalu, Pittsburgh . SS C 68 Kevin Mawae 64 Jeff Hartings C 57 Olin Kreutz 78 Matt Birk 31 Roy Williams, Dallas . SS 47 John Lynch, Denver . FS RG 68 Will Shields 54 Brian Waters RG 62 Marco Rivera 76 Steve Hutchinson 32 Dre’ Bly, Detroit . CB 49 Tony Richardson, Kansas City . FB RT 78 Tarik Glenn 77 Marvel Smith RT 76 Orlando Pace 72 Tra Thomas 32 Michael Lewis, Philadelphia. SS 51 James Farrior, Pittsburgh . ILB TE 85 Antonio Gates 88 Tony Gonzalez TE 83 Alge Crumpler 82 Jason Witten 33 William Henderson, Green Bay . -

Special Edition

The Patriot Special Issue January 21, 2005 Senior Directed Cabaret takes center stage Jamie Valentine ‘05 direct, and this year’s directors are Meghan Mucciarelli and Mike The Senior Directed Cabaret is a DiMatessa. tradition begun ten years ago with the When she found out, Mucciarelli class of 1996. It was started as a said, “I jumped up and down and fundraiser for Project Graduation, screamed like a little girl, honestly.” which was also founded that same year. DiMatessa said, “I’ve wanted to In the past decade, this show has do this since freshman year. I want to earned a reputation as an off-the-wall be a director, so this is a great chance funny and very relatable production. to get some experience. And I was In ’96, then-seniors Beth excited to work with Meghan.” Wodnick and Brian Nocella were the Directing a show like this one is first directors. Since then, two seniors no easy task. The Senior Directed who are dedicated to theater at Cabaret is made up of several skits, all Township have been chosen by the selected, cast, and directed by previous year’s cast and crew as co- Mucciarelli and DiMatessa. Over the directors every year. summer, they read through dozens of It is an honor to be chosen to plays and episodes of TV shows to decide which ones would work best. Jamie Valentine / The Patriot The chosen skits range Directors Mike DiMatessa (left) and Meghan Mucciarelli from serious to romantic (center) work on a scene with actor, Carl Jewell ‘07. -

Nfl) Retirement System

S. HRG. 110–1177 OVERSIGHT OF THE NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE (NFL) RETIREMENT SYSTEM HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION SEPTEMBER 18, 2007 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 76–327 PDF WASHINGTON : 2012 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:26 Oct 23, 2012 Jkt 075679 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\DOCS\76327.TXT JACKIE SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii, Chairman JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia TED STEVENS, Alaska, Vice Chairman JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota TRENT LOTT, Mississippi BARBARA BOXER, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas BILL NELSON, Florida OLYMPIA J. SNOWE, Maine MARIA CANTWELL, Washington GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey JOHN ENSIGN, Nevada MARK PRYOR, Arkansas JOHN E. SUNUNU, New Hampshire THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware JIM DEMINT, South Carolina CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri DAVID VITTER, Louisiana AMY KLOBUCHAR, Minnesota JOHN THUNE, South Dakota MARGARET L. CUMMISKY, Democratic Staff Director and Chief Counsel LILA HARPER HELMS, Democratic Deputy Staff Director and Policy Director CHRISTINE D. KURTH, Republican Staff Director and General Counsel PAUL NAGLE, Republican Chief Counsel (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:26 Oct 23, 2012 Jkt 075679 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\GPO\DOCS\76327.TXT JACKIE C O N T E N T S Page Hearing held on September 18, 2007 .................................................................... -

Iles Herald- Spectator ;

-a ]...ILESHERALD- SPECTATOR ; -e. S1.50 Thursday, June 29,2017 nilesheraldspectator.com GO Riggio's final days All rights reserved Iconic restaurant in Nues to close 65 years after Chicago opening.Page 4 STEVE JOHNSTON/PIONEER PRESS A bright future in store this holiday Where to find Fourth of July fireworks and parades in your community Page 17 SPORTS MARK KODIAK UKENA/PIONEEP PRESS Forward thinking i MIKE ISAACS/ PIONEER PRESS PDL team gives area soccer players a Tony Rigglo, owner of Riggios restaurant In Nues, talks on iune 2 about the long history of tI'e restaurant, which began 65 years chance to prepare for college, audition for ago. The Riggios are closing the restaurant Aug. 27. next level. Page 31 ILLINOIS HOLOCAUST MUSEUM & EDUCATION CENTER 9603 Woods Drive, Skokie Advance tickets recommended: SPECIAL EXHtBTION: JUL. 16 - NOV. 12, 2017 ilholocaustmuseum.org/billgraham 2 SHOUT OUT o NILES HERALD- SPECTATOR nilesheraldspectator.com Kim Hacki, new businessco-owner Jim Rotche, General Manager Kim Hacki and her husband, ofcome back Craig, opened Fast Signs in the Q: A movie you'd recom- Phil Junk, Suburban Editor 3400 block of Dempster Street in mend? John Puterbaugh, Pioneer Press Editor: Skokie at the beginning ofthe yeat A: The most recent I saw that I ago Tribune Publication 312-222-2337; [email protected] In addition to a graphic design thought was very interesting was Georgia Garvey, Managing Editor background, Hacki said she has "Founder." It was interesting the Matt Bute, Vice President of Advertising also spent much time in retail, way McDonald's got started. -

A Giant Whiff: Why the New CBA Fails Baseball's Smartest Small Market Franchises

DePaul Journal of Sports Law Volume 4 Issue 1 Summer 2007: Symposium - Regulation of Coaches' and Athletes' Behavior and Related Article 3 Contemporary Considerations A Giant Whiff: Why the New CBA Fails Baseball's Smartest Small Market Franchises Jon Berkon Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jslcp Recommended Citation Jon Berkon, A Giant Whiff: Why the New CBA Fails Baseball's Smartest Small Market Franchises, 4 DePaul J. Sports L. & Contemp. Probs. 9 (2007) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jslcp/vol4/iss1/3 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Sports Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A GIANT WHIFF: WHY THE NEW CBA FAILS BASEBALL'S SMARTEST SMALL MARKET FRANCHISES INTRODUCTION Just before Game 3 of the World Series, viewers saw something en- tirely unexpected. No, it wasn't the sight of the Cardinals and Tigers playing baseball in late October. Instead, it was Commissioner Bud Selig and Donald Fehr, the head of Major League Baseball Players' Association (MLBPA), gleefully announcing a new Collective Bar- gaining Agreement (CBA), thereby guaranteeing labor peace through 2011.1 The deal was struck a full two months before the 2002 CBA had expired, an occurrence once thought as likely as George Bush and Nancy Pelosi campaigning for each other in an election year.2 Baseball insiders attributed the deal to the sport's economic health. -

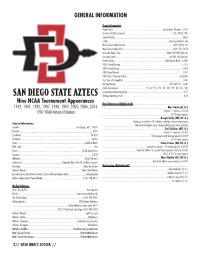

San Diego State Aztecs Starters Returning/Lost

GENERAL INFORMATION Team Information Head Coach ................................................................................. Lev Kirshner (Rutgers, 1991) Record at SDSU (Seasons) .............................................................................138-167-55 (19) Career Record ................................................................................................................Same E-mail .................................................................................................. [email protected] Men’s Soccer Office Phone ............................................................................. (619) 594-0136 Men’s Soccer Office Fax ................................................................................. (619) 594-1674 Associate Head Coach ...........................................................................Matt Hall (20th Season) Assistant Coach ......................................................................................Josh Hill (3rd Season) Home Facility ..................................................................................SDSU Sports Deck (1,250) 2018 Overall Record .................................................................................................... 7-10-1 2018 Home Record ....................................................................................................... 5-5-0 2018 Road Record ........................................................................................................ 2-5-1 2018 Pac-12 Record/Finish ......................................................................................2-8-0/6th -

Jim Brown, Ernie Davis and Floyd Little

The Ensley Athletic Center is the latest major facilities addition to the Lampe Athletics Complex. The $13 million building was constructed in seven months and opened in January 2015. It serves as an indoor training center for the football program, as well as other sports. A multi- million dollar gift from Cliff Ensley, a walk-on who earned a football scholarship and became a three-sport standout at Syracuse in the late 1960s, combined with major gifts from Dick and Jean Thompson, made the construction of the 87,000 square-foot practice facility possible. The construction of Plaza 44, which will The Ensley Athletic Center includes a 7,600 tell the story of Syracuse’s most famous square-foot entry pavilion that houses number, has begun. A gathering area meeting space and restrooms. outside the Ensley Athletic Center made possible by the generosity of Jeff and Jennifer Rubin, Plaza 44 will feature bronze statues of the three men who defi ne the Legend of 44 — Jim Brown, Ernie Davis and Floyd Little. Syracuse defeated Minnesota in the 2013 Texas Bowl for its third consecutive bowl victory and fi fth in its last six postseason trips. Overall, the Orange has earned invitations to every bowl game that is part of the College Football Playoff and holds a 15-9-1 bowl record. Bowl Game (Date) Result Orange Bowl (Jan. 1, 1953) Alabama 61, Syracuse 6 Cotton Bowl (Jan. 1, 1957) TCU 28, Syracuse 27 Orange Bowl (Jan. 1, 1959) Oklahoma 21, Syracuse 6 Cotton Bowl (Jan. 1, 1960) Syracuse 23, Texas 14 Liberty Bowl (Dec.