Morton R. Godine Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trans* Politics and the Feminist Project: Revisiting the Politics of Recognition to Resolve Impasses

Politics and Governance (ISSN: 2183–2463) 2020, Volume 8, Issue 3, Pages 312–320 DOI: 10.17645/pag.v8i3.2825 Article Trans* Politics and the Feminist Project: Revisiting the Politics of Recognition to Resolve Impasses Zara Saeidzadeh * and Sofia Strid Department of Gender Studies, Örebro University, 702 81 Örebro, Sweden; E-Mails: [email protected] (Z.S.), [email protected] (S.S.) * Corresponding author Submitted: 24 January 2020 | Accepted: 7 August 2020 | Published: 18 September 2020 Abstract The debates on, in, and between feminist and trans* movements have been politically intense at best and aggressively hostile at worst. The key contestations have revolved around three issues: First, the question of who constitutes a woman; second, what constitute feminist interests; and third, how trans* politics intersects with feminist politics. Despite decades of debates and scholarship, these impasses remain unbroken. In this article, our aim is to work out a way through these impasses. We argue that all three types of contestations are deeply invested in notions of identity, and therefore dealt with in an identitarian way. This has not been constructive in resolving the antagonistic relationship between the trans* movement and feminism. We aim to disentangle the antagonism within anti-trans* feminist politics on the one hand, and trans* politics’ responses to that antagonism on the other. In so doing, we argue for a politics of status-based recognition (drawing on Fraser, 2000a, 2000b) instead of identity-based recognition, highlighting individuals’ specific needs in soci- ety rather than women’s common interests (drawing on Jónasdóttir, 1991), and conceptualising the intersections of the trans* movement and feminism as mutually shaping rather than as trans* as additive to the feminist project (drawing on Walby, 2007, and Walby, Armstrong, and Strid, 2012). -

Survival. Activism. Feminism?: Exploring the Lives of Trans* Individuals in Chicago

SURVIVAL. ACTIVISM. FEMINISM? Survival. Activism. Feminism?: Exploring the Lives of Trans* Individuals in Chicago Some radical lesbian feminists, like Sheila Jeffreys (1997, 2003, 2014) argue that trans individuals are destroying feminism by succumbing to the greater forces of the patriarchy and by opting for surgery, thus conforming to normative ideas of sex and gender. Jeffreys is not alone in her views. Janice Raymond (1994, 2015) also maintains that trans individuals work either as male-to-females (MTFs) to uphold stereotypes of femininity and womanhood, or as female-to-males (FTMs) to join the ranks of the oppressors, support the patriarchy, and embrace hegemonic masculinity. Both Jeffreys and Raymond conclude that sex/gender is fixed by genitals at birth and thus deny trans individuals their right to move beyond the identities that they were assigned at birth. Ironically, a paradox is created by these radical lesbians feminist theorists, who deny trans individuals the right to define their own lives and control their own bodies. Such essentialist discourse, however, fails to recognize the oppression, persecution, and violence to which trans individuals are subjected because they do not conform to the sex that they were assigned at birth. Jeffreys (1997) also claims there is an emergency and that the human rights of those who are now identifying as trans are being violated. These critiques are not only troubling to me, as a self-identified lesbian feminist, but are also illogical and transphobic. My research, with trans identified individuals in Chicago, presents a different story and will show another side of the complex relationship between trans and lesbian feminist communities. -

Delayed Critique: on Being Feminist, Time and Time Again

Delayed Critique: On Being Feminist, Time and Time Again In “On Being in Time with Feminism,” Robyn Emma McKenna is a Ph.D. candidate in English and Wiegman (2004) supports my contention that history, Cultural Studies at McMaster University. She is the au- theory, and pedagogy are central to thinking through thor of “‘Freedom to Choose”: Neoliberalism, Femi- the problems internal to feminism when she asks: “… nism, and Childcare in Canada.” what learning will ever be final?” (165) Positioning fem- inism as neither “an antidote to [n]or an ethical stance Abstract toward otherness,” Wiegman argues that “feminism it- In this article, I argue for a systematic critique of trans- self is our most challenging other” (164). I want to take phobia in feminism, advocating for a reconciling of seriously this claim in order to consider how feminism trans and feminist politics in community, pedagogy, is a kind of political intimacy that binds a subject to the and criticism. I claim that this critique is both delayed desire for an “Other-wise” (Thobani 2007). The content and productive. Using the Michigan Womyn’s Music of this “otherwise” is as varied as the projects that femi- Festival as a cultural archive of gender essentialism, I nism is called on to justify. In this paper, I consider the consider how rereading and revising politics might be marginalization of trans-feminism across mainstream, what is “essential” to feminism. lesbian feminist, and academic feminisms. Part of my interest in this analysis is the influence of the temporal Résumé on the way in which certain kinds of feminism are given Dans cet article, je défends l’idée d’une critique systéma- primacy in the representation of feminism. -

Whipping Girl

Table of Contents Title Page Dedication Introduction Trans Woman Manifesto PART 1 - Trans/Gender Theory Chapter 1 - Coming to Terms with Transgen- derism and Transsexuality Chapter 2 - Skirt Chasers: Why the Media Depicts the Trans Revolution in ... Trans Woman Archetypes in the Media The Fascination with “Feminization” The Media’s Transgender Gap Feminist Depictions of Trans Women Chapter 3 - Before and After: Class and Body Transformations 3/803 Chapter 4 - Boygasms and Girlgasms: A Frank Discussion About Hormones and ... Chapter 5 - Blind Spots: On Subconscious Sex and Gender Entitlement Chapter 6 - Intrinsic Inclinations: Explaining Gender and Sexual Diversity Reconciling Intrinsic Inclinations with Social Constructs Chapter 7 - Pathological Science: Debunking Sexological and Sociological Models ... Oppositional Sexism and Sex Reassignment Traditional Sexism and Effemimania Critiquing the Critics Moving Beyond Cissexist Models of Transsexuality Chapter 8 - Dismantling Cissexual Privilege Gendering Cissexual Assumption Cissexual Gender Entitlement The Myth of Cissexual Birth Privilege Trans-Facsimilation and Ungendering 4/803 Moving Beyond “Bio Boys” and “Gen- etic Girls” Third-Gendering and Third-Sexing Passing-Centrism Taking One’s Gender for Granted Distinguishing Between Transphobia and Cissexual Privilege Trans-Exclusion Trans-Objectification Trans-Mystification Trans-Interrogation Trans-Erasure Changing Gender Perception, Not Performance Chapter 9 - Ungendering in Art and Academia Capitalizing on Transsexuality and Intersexuality -

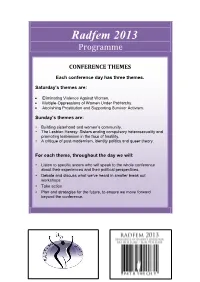

Radfem 2013 Programme

Radfem 2013 Programme CONFERENCE THEMES Each conference day has three themes. Saturday’s themes are: Eliminating Violence Against Women. Multiple-Oppressions of Women Under Patriarchy. Abolishing Prostitution and Supporting Survivor Activism. Sunday’s themes are: Building sisterhood and women’s community. The Lesbian Heresy: Sisters ending compulsory heterosexuality and promoting lesbianism in the face of hostility. A critique of post-modernism, identity politics and queer theory. For each theme, throughout the day we will: Listen to specific sisters who will speak to the whole conference about their experiences and their political perspectives. Debate and discuss what we’ve heard in smaller break out workshops Take action Plan and strategise for the future, to ensure we move forward beyond the conference. Programme Timetable SATURDAY, 8 JUNE TIME / DESCRIPTION ACTIVITY 8.30 – 9.00 Arrive, sign in, optional activities. 9.00 – 9.10 Vita and Lakha Mahila Welcome 9.10 – 9.40 Choose one of the following: Connecting with A. LIVING LIBRARY: TELLING OUR STORIES - RADFEM STORY Sisters BOOKS We all have a herstory and we are all unique with empowering stories to tell about how we are survivors of patriarchy. Come and be a story book and/or listen to other story books about our struggles and our survival. A couple of examples are: “I live in a women’s community” or “I am a political lesbian”. Decide on at least one story before you arrive to this workshop and we’ll help you do the rest. Radfem story books will be told throughout the 2 days and you can tell as many stories as you like to as many women as you like. -

Representing Trans Road Narratives in Mainstream Cinema (1970-2016)

Wish You Were Here: Representing Trans Road Narratives in Mainstream Cinema (1970-2016) by Evelyn Deshane A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2019 © Evelyn Deshane 2019 Examining Committee Membership The following served on the Examining Committee for this thesis. The decision of the Examining Committee is by majority vote. External Examiner Dr. Dan Irving Associate Professor Supervisor Dr. Andrew McMurry Associate Professor Internal-external Member Dr. Kim Nguyen Assistant Professor Internal Members Dr. Gordon Slethaug Adjunct Professor Dr. Victoria Lamont Associate Professor ii Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. iii Abstract When Christine Jorgensen stepped off a plane in New York City from Denmark in 1952, she became one of the first instances of trans celebrity, and her intensely popular story was adapted from an article to a memoir and then a film in 1970. Though not the first trans person recorded in history, Jorgensen's story is crucial in the history of trans representation because her journey embodies the archetypal trans narrative which moves through stages of confusion, discovery, cohesion, and homecoming. This structure was solidified in memoirs of the 1950- 1970s, and grew in popularity alongside the booming film industry in the wake of the Hays Production Code, which finally allowed directors, producers, and writers to depict trans and gender nonconforming characters and their stories on-screen. -

Transgender History / by Susan Stryker

u.s. $12.95 gay/Lesbian studies Craving a smart and Comprehensive approaCh to transgender history historiCaL and Current topiCs in feminism? SEAL Studies Seal Studies helps you hone your analytical skills, susan stryker get informed, and have fun while you’re at it! transgender history HERE’S WHAT YOU’LL GET: • COVERAGE OF THE TOPIC IN ENGAGING AND AccESSIBLE LANGUAGE • PhOTOS, ILLUSTRATIONS, AND SIDEBARS • READERS’ gUIDES THAT PROMOTE CRITICAL ANALYSIS • EXTENSIVE BIBLIOGRAPHIES TO POINT YOU TO ADDITIONAL RESOURCES Transgender History covers American transgender history from the mid-twentieth century to today. From the transsexual and transvestite communities in the years following World War II to trans radicalism and social change in the ’60s and ’70s to the gender issues witnessed throughout the ’90s and ’00s, this introductory text will give you a foundation for understanding the developments, changes, strides, and setbacks of trans studies and the trans community in the United States. “A lively introduction to transgender history and activism in the U.S. Highly readable and highly recommended.” SUSAN —joanne meyerowitz, professor of history and american studies, yale University, and author of How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality In The United States “A powerful combination of lucid prose and theoretical sophistication . Readers STRYKER who have no or little knowledge of transgender issues will come away with the foundation they need, while those already in the field will find much to think about.” —paisley cUrrah, political -

LGBTQ Policy Journal at the John F

LGBTQ Policy Journal at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University Volume 11 Spring 2021 ACKNOWLEDGMENT & APPRECIATION Editorial Staff Kamille Washington, Editor-in-Chief Elizabeth Zwart, Editor-in-Chief Marty Amaya, Managing Editor Morgan Benson, Associate Editor Ben Demers, Associate Editor Craig Johnson, Associate Editor Rachel Rostad, Associate Editor Jacob Waggoner, Associate Editor Individual Supporters Tim McCarthy, Faculty Advisor Richard Parker, Faculty Advisor Martha Foley, Publisher Nicole Lewis, Copyeditor Cerise Steel, Designer A Note of Gratitude Thank you to Open Gate, without whose support we would not have been able to produce as inclusive and meaningful a journal. Your generosity and commitment to justice were crucial in making this journal what is it. 2 LGBTQ Policy Journal 66 Taking off the ‘Masc’ Contents How Gay-Identifying Men Perceive and Navigate Hyper-Masculinity and “Mascing” 4 Letter from the Editor Culture Online By Alexander Löwstedt Granath 5 Absolute Sovereignty Exceptions as well as Legal 77 The United States Is Not Safe Obligations of States to Protect for LGBT Refugees the Rights of LGBTQI and Gender A Call to Abandon the Canada-United Diverse Persons (GDP), States Safe Third Country Agreement By Portia Comenetia Allen, James By Ella Hartsoe Katlego Chibamba, Shawn Mugisha, 80 Exploring the Need for and and Augusta Aondoaver Yaakugh Benefits of LGBTQA Faculty and 13 Up to Us Staff Groups in Higher Education A Community-Led Needs Assessment of By Ariel Schorr Lesnick Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming 90 Mutual Aid as a Queer Asians and Pacific Islanders in the Bay Intervention in Public Library Area By APIENC Service By Flan Park 24 Breaking the “First Rule of Masculinity” 93 Carving Spaces for A Conversation with Thomas Page McBee Engagement in Indonesia By Morgan Benson An Interview with Hendrika Mayora Victoria Kelan 31 Religious Equity By Eki Ramadhan A Path to Greater LGBTQ Inclusion By Rev. -

Reiterations of Misogyny Embedded in Lesbian and Feminist Communities' Framing of Lesbian Femme Identities

Uncompromising Positions: Reiterations of Misogyny Embedded in Lesbian and Feminist Communities' Framing of Lesbian Femme Identities Anika Stafford is a PhD student with the Introduction Centre for Women's and Gender Studies at There is a popular conception that the University of British Columbia. Her work misogyny, a hatred of women, is solely has been published in anthologies such as perpetuated by "men" as a group against Queers in American Popular Culture and "women" as a group. This notion has Who's Your Daddy? And Other Writings on contributed to the idea that lesbians and/or Queer Parenting. She is currently conducting feminists would not be capable of institutional ethnographic research on perpetuating misogyny. However, misogynist transgender people and elementary school conceptualizations of female bodies have experience. created insidious cultural norms wherein associations with traits deemed feminine Abstract come to be seen in a derogatory light. As Queer femmes in 1950s bar cultures were everyone, regardless of gender or gender often not viewed as "real lesbians;" radical expression, is indoctrinated into dominant feminism condemned femmes as trying to cultural misogynist systems of power, please patriarchy. This paper investigates everyone is implicated in reproducing or ways such views regarding femmes reiterate challenging such norms. misogynist notions of female bodies. It places Within feminist/queer theory, much femme narratives challenging such debate has taken place regarding lesbian conceptualizations as contesting butch-femme bar cultures of the 1950s and counter-cultural reiterations of misogyny. 1960s. Despite myriad debates regarding Résumé revolutionary potentials of such gendered Les femmes queer dans la culture des bars identities, an examination of how views of des années 50 souvent n’étaient pas vues femininity within feminist/queer discourses comme de “vraies lesbiennes”, le féminisme can reiterate misogynist views of female radical condamnait les femmes queer disant bodies has remained under-theorized. -

Sex and the State

COURSE SYLLABUS POLI 3426 – Sex and the State Department of Political Science Dalhousie University Class Time: Wednesday 1:30-4:30 Location: Tupper Theatre Instructor: Dr. Margaret Denike Office: 362 Henry Hicks Administration Building Telephone: (902) 494-6298 Email: [email protected] (please make sure to use this email address, rather than the BLS system for any correspondence) Office Hours: Monday 10-12, or by appointment Teaching Asst.: Katie Harper COURSE DESCRIPTION With a focus sexual minorities, this course will consider the role of the state and other institutions in the social, moral and legal production and regulation of sex and gender, particularly in Canada and the US. It will begin with a brief historical overview of the relation between the church and the state in the development of prescriptions for sexual conduct, and in the refinement of laws and policies that have been implicated in sex- and gender-based discrimination and normative formations over the years. It will also examine strategies and initiatives of sexual minorities for social and legal reform, particularly in the past century. We will also address a range of contemporary topics such as the initiatives –and the implications- of engaging or advancing equality human rights in courts and legislatures; the politics of relationship recognition; same-sex marriage and appeals to religious freedom; and the role of the state in regulating sex and gender identity. REQUIRED TEXTS: • The course materials are available electronically, either through web links to library or internet resources (provided on the syllabus), or in PDF format through the BLS system. ASSIGNMENT PROFILE Class Participation 10% Essay 1 30% (2000 words max; due Feb 6) 1 Essay 30% (2000 words max; due Mar 5) Test 30% (March 26) GRADING PROFILE A+ = 88%+ B+ = 77- 79% C+ = 67- 69% D = 50-59% A = 84 - 87% B = 74 - 76% C = 64 - 66% F = 0 - 49% A- = 80-83% B- = 70 - 73% C- = 60 - 63% CLASS PARTICIPATION The preparation and participation of each and every student in the class discussions will determine the success of the course. -

Helen Hester, Xenofeminism (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2018), 169 P

Contradictions A Journal for Critical Thought Volume 3 number 2 (2019) Helen Hester, Xenofeminism (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2018), 169 p. ISBN 9781509520633. As feminists we inhabit many houses. Nancy Fraser is a feminist, Sheryl Sandberg is a feminist, Sheila Jeffreys is a feminist. But each one means something quite different, and so we cannot simply take the claim at face value. Thus, xenofeminism is feminism, but a variety which stands in contrast to other developments in recent times. Helen Hester’s book describes itself as an admixture of cyberfeminism, posthumanism, ac- celerationism, material feminism, “and so on.” It is divided into three uneven chapters; “What is Xenofeminism?,” “Xenofeminist Futurities”, and “Xenofeminist Technologies.” So let us now take a look at Xenofeminist Futurities. In 2014 Deep Green Resistance, a US-based militant ecological movement, hit something of a bump in the road – it could even be called a scandal if it wasn’t of such manifestly ideological content – when they expelled a leading member for supporting the heresy of transgenderism. This was defended on the grounds that the movement regarded gender as a social construct to be opposed, and so antithetical to their militant green politics. Once again, the contest between biological sex and gender identity had fallen victim to sexual fundamentalism.1 Hester’s chapter on “Futurities” deals with this element of fundamentalism, while also incorporating some of the analysis of Lee Edelman’s classic of Queer Theory, No Future.2 Edelman sees the Child as a heteronormative symbol of the (political) future. His response is a refusal of the Child, a refusal which Hester picks up on, and asks how we can fight for a more emancipatory future without falling back on the theme of making the world a better place for our children. -

Transfeminisms

Cáel M. Keegan—Sample syllabus (proposed) This is a proposed syllabus for an advanced WGSS seminar. Transfeminisms Course Overview:_________________________________________________ Description: Recent gains in visibility and recognition for transgender people have reactivated long- standing arguments over whether feminism can or should support trans rights, and whether transgender people should be considered feminist subjects. Rather than re- staging this decades-long debate as a zero-sum game, this course traces how—far from eradicating each other—“trans” and “feminist” share a co-constitutive history, each requiring and evolving the other. To quote Jack Halberstam from his talk "Why We Need a Transfeminism" at UC Santa Cruz in 2002, “Transgender is the gender trouble that feminism has been talking about all along.” We will explore the unfolding of the transfeminist imaginary from its roots in gay liberation and woman of color feminisms, through the sex wars of the 1970s and 80s, and into the 21st century. Throughout, we will examine a number of key points in feminist discourse and politics at which the paradoxical formation “transfeminism” becomes legible as a framework, necessity, legacy, or impending future. We will uncover transfeminist histories and grapple with the complexity of transfeminist communities, activisms, and relations. We will explore transfeminist world-building and practice our own transfeminist visions for the world. Required Text: Transgender Studies Quarterly, “Trans/Feminisms.” Eds. Susan Stryker and Talia Mae Bettcher. 3.1-2 (May 2016). The required text is available at the bookstore. All other readings are available via electronic reserve on Blackboard. Required Films: Films are on course reserve for viewing at the library.