Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survival. Activism. Feminism?: Exploring the Lives of Trans* Individuals in Chicago

SURVIVAL. ACTIVISM. FEMINISM? Survival. Activism. Feminism?: Exploring the Lives of Trans* Individuals in Chicago Some radical lesbian feminists, like Sheila Jeffreys (1997, 2003, 2014) argue that trans individuals are destroying feminism by succumbing to the greater forces of the patriarchy and by opting for surgery, thus conforming to normative ideas of sex and gender. Jeffreys is not alone in her views. Janice Raymond (1994, 2015) also maintains that trans individuals work either as male-to-females (MTFs) to uphold stereotypes of femininity and womanhood, or as female-to-males (FTMs) to join the ranks of the oppressors, support the patriarchy, and embrace hegemonic masculinity. Both Jeffreys and Raymond conclude that sex/gender is fixed by genitals at birth and thus deny trans individuals their right to move beyond the identities that they were assigned at birth. Ironically, a paradox is created by these radical lesbians feminist theorists, who deny trans individuals the right to define their own lives and control their own bodies. Such essentialist discourse, however, fails to recognize the oppression, persecution, and violence to which trans individuals are subjected because they do not conform to the sex that they were assigned at birth. Jeffreys (1997) also claims there is an emergency and that the human rights of those who are now identifying as trans are being violated. These critiques are not only troubling to me, as a self-identified lesbian feminist, but are also illogical and transphobic. My research, with trans identified individuals in Chicago, presents a different story and will show another side of the complex relationship between trans and lesbian feminist communities. -

Delayed Critique: on Being Feminist, Time and Time Again

Delayed Critique: On Being Feminist, Time and Time Again In “On Being in Time with Feminism,” Robyn Emma McKenna is a Ph.D. candidate in English and Wiegman (2004) supports my contention that history, Cultural Studies at McMaster University. She is the au- theory, and pedagogy are central to thinking through thor of “‘Freedom to Choose”: Neoliberalism, Femi- the problems internal to feminism when she asks: “… nism, and Childcare in Canada.” what learning will ever be final?” (165) Positioning fem- inism as neither “an antidote to [n]or an ethical stance Abstract toward otherness,” Wiegman argues that “feminism it- In this article, I argue for a systematic critique of trans- self is our most challenging other” (164). I want to take phobia in feminism, advocating for a reconciling of seriously this claim in order to consider how feminism trans and feminist politics in community, pedagogy, is a kind of political intimacy that binds a subject to the and criticism. I claim that this critique is both delayed desire for an “Other-wise” (Thobani 2007). The content and productive. Using the Michigan Womyn’s Music of this “otherwise” is as varied as the projects that femi- Festival as a cultural archive of gender essentialism, I nism is called on to justify. In this paper, I consider the consider how rereading and revising politics might be marginalization of trans-feminism across mainstream, what is “essential” to feminism. lesbian feminist, and academic feminisms. Part of my interest in this analysis is the influence of the temporal Résumé on the way in which certain kinds of feminism are given Dans cet article, je défends l’idée d’une critique systéma- primacy in the representation of feminism. -

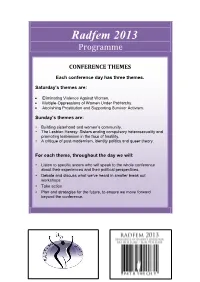

Radfem 2013 Programme

Radfem 2013 Programme CONFERENCE THEMES Each conference day has three themes. Saturday’s themes are: Eliminating Violence Against Women. Multiple-Oppressions of Women Under Patriarchy. Abolishing Prostitution and Supporting Survivor Activism. Sunday’s themes are: Building sisterhood and women’s community. The Lesbian Heresy: Sisters ending compulsory heterosexuality and promoting lesbianism in the face of hostility. A critique of post-modernism, identity politics and queer theory. For each theme, throughout the day we will: Listen to specific sisters who will speak to the whole conference about their experiences and their political perspectives. Debate and discuss what we’ve heard in smaller break out workshops Take action Plan and strategise for the future, to ensure we move forward beyond the conference. Programme Timetable SATURDAY, 8 JUNE TIME / DESCRIPTION ACTIVITY 8.30 – 9.00 Arrive, sign in, optional activities. 9.00 – 9.10 Vita and Lakha Mahila Welcome 9.10 – 9.40 Choose one of the following: Connecting with A. LIVING LIBRARY: TELLING OUR STORIES - RADFEM STORY Sisters BOOKS We all have a herstory and we are all unique with empowering stories to tell about how we are survivors of patriarchy. Come and be a story book and/or listen to other story books about our struggles and our survival. A couple of examples are: “I live in a women’s community” or “I am a political lesbian”. Decide on at least one story before you arrive to this workshop and we’ll help you do the rest. Radfem story books will be told throughout the 2 days and you can tell as many stories as you like to as many women as you like. -

Reiterations of Misogyny Embedded in Lesbian and Feminist Communities' Framing of Lesbian Femme Identities

Uncompromising Positions: Reiterations of Misogyny Embedded in Lesbian and Feminist Communities' Framing of Lesbian Femme Identities Anika Stafford is a PhD student with the Introduction Centre for Women's and Gender Studies at There is a popular conception that the University of British Columbia. Her work misogyny, a hatred of women, is solely has been published in anthologies such as perpetuated by "men" as a group against Queers in American Popular Culture and "women" as a group. This notion has Who's Your Daddy? And Other Writings on contributed to the idea that lesbians and/or Queer Parenting. She is currently conducting feminists would not be capable of institutional ethnographic research on perpetuating misogyny. However, misogynist transgender people and elementary school conceptualizations of female bodies have experience. created insidious cultural norms wherein associations with traits deemed feminine Abstract come to be seen in a derogatory light. As Queer femmes in 1950s bar cultures were everyone, regardless of gender or gender often not viewed as "real lesbians;" radical expression, is indoctrinated into dominant feminism condemned femmes as trying to cultural misogynist systems of power, please patriarchy. This paper investigates everyone is implicated in reproducing or ways such views regarding femmes reiterate challenging such norms. misogynist notions of female bodies. It places Within feminist/queer theory, much femme narratives challenging such debate has taken place regarding lesbian conceptualizations as contesting butch-femme bar cultures of the 1950s and counter-cultural reiterations of misogyny. 1960s. Despite myriad debates regarding Résumé revolutionary potentials of such gendered Les femmes queer dans la culture des bars identities, an examination of how views of des années 50 souvent n’étaient pas vues femininity within feminist/queer discourses comme de “vraies lesbiennes”, le féminisme can reiterate misogynist views of female radical condamnait les femmes queer disant bodies has remained under-theorized. -

Sex and the State

COURSE SYLLABUS POLI 3426 – Sex and the State Department of Political Science Dalhousie University Class Time: Wednesday 1:30-4:30 Location: Tupper Theatre Instructor: Dr. Margaret Denike Office: 362 Henry Hicks Administration Building Telephone: (902) 494-6298 Email: [email protected] (please make sure to use this email address, rather than the BLS system for any correspondence) Office Hours: Monday 10-12, or by appointment Teaching Asst.: Katie Harper COURSE DESCRIPTION With a focus sexual minorities, this course will consider the role of the state and other institutions in the social, moral and legal production and regulation of sex and gender, particularly in Canada and the US. It will begin with a brief historical overview of the relation between the church and the state in the development of prescriptions for sexual conduct, and in the refinement of laws and policies that have been implicated in sex- and gender-based discrimination and normative formations over the years. It will also examine strategies and initiatives of sexual minorities for social and legal reform, particularly in the past century. We will also address a range of contemporary topics such as the initiatives –and the implications- of engaging or advancing equality human rights in courts and legislatures; the politics of relationship recognition; same-sex marriage and appeals to religious freedom; and the role of the state in regulating sex and gender identity. REQUIRED TEXTS: • The course materials are available electronically, either through web links to library or internet resources (provided on the syllabus), or in PDF format through the BLS system. ASSIGNMENT PROFILE Class Participation 10% Essay 1 30% (2000 words max; due Feb 6) 1 Essay 30% (2000 words max; due Mar 5) Test 30% (March 26) GRADING PROFILE A+ = 88%+ B+ = 77- 79% C+ = 67- 69% D = 50-59% A = 84 - 87% B = 74 - 76% C = 64 - 66% F = 0 - 49% A- = 80-83% B- = 70 - 73% C- = 60 - 63% CLASS PARTICIPATION The preparation and participation of each and every student in the class discussions will determine the success of the course. -

Helen Hester, Xenofeminism (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2018), 169 P

Contradictions A Journal for Critical Thought Volume 3 number 2 (2019) Helen Hester, Xenofeminism (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2018), 169 p. ISBN 9781509520633. As feminists we inhabit many houses. Nancy Fraser is a feminist, Sheryl Sandberg is a feminist, Sheila Jeffreys is a feminist. But each one means something quite different, and so we cannot simply take the claim at face value. Thus, xenofeminism is feminism, but a variety which stands in contrast to other developments in recent times. Helen Hester’s book describes itself as an admixture of cyberfeminism, posthumanism, ac- celerationism, material feminism, “and so on.” It is divided into three uneven chapters; “What is Xenofeminism?,” “Xenofeminist Futurities”, and “Xenofeminist Technologies.” So let us now take a look at Xenofeminist Futurities. In 2014 Deep Green Resistance, a US-based militant ecological movement, hit something of a bump in the road – it could even be called a scandal if it wasn’t of such manifestly ideological content – when they expelled a leading member for supporting the heresy of transgenderism. This was defended on the grounds that the movement regarded gender as a social construct to be opposed, and so antithetical to their militant green politics. Once again, the contest between biological sex and gender identity had fallen victim to sexual fundamentalism.1 Hester’s chapter on “Futurities” deals with this element of fundamentalism, while also incorporating some of the analysis of Lee Edelman’s classic of Queer Theory, No Future.2 Edelman sees the Child as a heteronormative symbol of the (political) future. His response is a refusal of the Child, a refusal which Hester picks up on, and asks how we can fight for a more emancipatory future without falling back on the theme of making the world a better place for our children. -

Trafficking, Prostitution, and Inequalitya

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLC\46-2\HLC207.txt unknown Seq: 1 30-JUN-11 9:28 Trafficking, Prostitution, and Inequalitya Copyright Catharine A. MacKinnon 2009, 2010, 2011 ROMEO [F]amine is in thy cheeks, Need and oppression starveth in thine eyes, Contempt and beggary hangs upon thy back; The world is not thy friend nor the world’s law; The world affords no law to make thee rich; Then be not poor, but break it, and take this. APOTHECARY My poverty, but not my will, consents. ROMEO I pay thy poverty, and not thy will.* No one defends trafficking. There is no pro-sex-trafficking position any more than there is a public pro-slavery position for labor these days. The only issue is defining these terms so nothing anyone wants to defend is covered. It is hard to find overt defenders of inequality either, even as its legal definition is also largely shaped by existing practices the powerful want to keep. Prostitution is not like this. Some people are for it; they affirmatively support it. Many more regard it as politically correct to tolerate and oppose doing anything effective about it. Most assume that, if not exactly desirable, prostitution is necessary or inevitable and harmless. These views of prostitu- tion lie beneath and surround any debate on sex trafficking, whether prosti- tution is distinguished from trafficking or seen as indistinguishable from it, whether seen as a form of sexual freedom or understood as its ultimate de- nial. The debate on the underlying reality, and its relation to inequality, intensifies whenever doing anything effective about either prostitution or trafficking is considered. -

Womensst 392Ef

Sex and European Feminism during the “long nineteenth century” Bartlett Hall Rm 121 Tuesdays and Thursdays, 1:00-2:15pm Kirsten Leng [email protected] Office Hours: Thursdays 2:30-3:50pm 11D Bartlett Hall 1 Course Description Why has sex been a central preoccupation for feminism throughout its history? How have feminist attitudes towards sex changed over time, and how have attitudes varied amongst feminists themselves? What connections did feminists make between sexual reform, women’s rights, and broader social, political, and economic change? And what are the legacies of past feminist sexual politics for the present day? This course addresses these questions by exploring the history of feminist sexual politics in Europe over the course of the “long nineteenth century” (1789-1914), and will focus on developments in Britain, France, and Germany. We will examine feminists’ writings on and activism surrounding sex and sexuality to understand how definitions of sex, feminism, and sexual politics changed over time, and how issues of class and race shaped feminist sexual politics. We will also analyze contradictions, tensions, and continuities within diverse feminist approaches to sexuality, and assess similarities and differences amongst feminists from different national backgrounds. By adopting a focus on feminism and sexuality, this course offers a unique lens on the major events of modern European history. Requirements and Evaluation Participation: 30% This course will combine lecture and seminar formats. Each class, students are expected to complete the readings and actively participate in class discussions. If for any reason a student is unable to participate in this manner, s/he should contact me as soon as possible to make alternative arrangements. -

Feminist Sexual Politics in Historical Perspective Syllabus Fall 2013

Feminist Sexual Politics in Historical Perspective 754 Schermerhorn Extension Wednesdays, 4:10-6:00pm Dr. Kirsten Leng [email protected] Office Hours: TBD 757 Schermerhorn Extension 1 Course Description Why, and in what ways, has sex been a central issue for feminism throughout its history? How have feminist attitudes towards sex changed over time, and how did attitudes vary amongst feminists themselves? What connections did feminists make between sexual reform, women’s rights, and broader social, political, and economic change? And what are the legacies of past feminist sexual politics for the present day? This course addresses these questions by exploring the history of feminist sexual politics in Europe over the course of the “long nineteenth century,” that is, between the years 1789 and 1918, and will focus on developments in Britain, France, and Germany. We will examine feminists’ writings on and activism surrounding sex and sexuality to understand how definitions of “sex,” “feminism,” and “sexual politics” changed over time, and how issues of class and race shaped feminist sexual politics. We will also analyze contradictions, tensions and continuities within diverse feminist approaches to sexuality, and assess similarities and differences amongst feminists from different national backgrounds. Furthermore, by adopting a focus on feminism and sexuality, this course offers a unique lens on the major “world historical” events of modern European history. Requirements and Evaluation Participation: 30% Students are expected not only to complete the readings, but also to participate in class discussions. If for any reason a student is unable to participate in this manner, s/he should contact me as soon as possible to make alternative arrangements. -

Morton R. Godine Library

Electronic Reserve Document Please be advised that to use electronic material, you agree to the following: The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be "used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research." If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. For questions regarding electronic reserves, please contact the library at 617-879-7104. Type: Book Chapter Journal Article Other: ________________ Author: Title: Source: Publisher: Issue/Date: Pages: Trans* A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability Jack Halberstam cp UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Morton R. Godine Library University of California Press, one of the most distin guished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2018 by Jack Halberstam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Halberstam, Judith, 1961- author. Title: Trans* : a quick and quirky account of gender variability /Jack Halberstam. Description: Oakland, California : University of California Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references. -

Bisexual Politics: a Superior Form of Feminism?

Women’s Studies International Forum, Vol. 22, No. 3, pp. 273–285, 1999 Copyright © 1999 Elsevier Science Ltd Pergamon Printed in the USA. All rights reserved 0277-5395/99 $–see front matter PII S0277-5395(99)00020-5 BISEXUAL POLITICS: A SUPERIOR FORM OF FEMINISM? Sheila Jeffreys Department of Political Science, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia Synopsis — In this article, I shall examine the ideas and practices of the bisexual movement that has developed in the Western world in the last decade. I shall offer a lesbian feminist critique. Bisexual the- orists and activists have formulated critiques of lesbian feminism at their conferences and in anthologies of their writings. Lesbian feminists have been described as “gender fascists,” as monosexists, and as bi- phobic for their failure to embrace bisexuals in theory or in person, but little has been published from a lesbian feminist perspective on these developments. I argue that bisexual politics, rather than forming a superior form of feminism, tends toward a belief in the naturalness of desire, a revaluing of the hetero- sexual imperative that women should love men, and an undermining of the power and resistance in- volved in the lesbian feminist decision to choose for women and not men. © 1999 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. Over the last 10 years, a “bisexual movement” California in the 1970s (Weinberg, Williams, & has developed with conferences and anthologies Pryor, 1995). These male sexual freedom bi- full of ideas on bisexual theory and practice from sexuals adopted a bisexual identity which dis- the United States and the United Kingdom (Fir- tinguishes them from those very numerous estein, 1996; Hutchins & Kaahumanu, 1991; Rose men in heterosexual relationships who engage & Stevens, 1996; Tucker, 1995; Weise, 1992). -

![[Vol. Xxix, No. 2 1991] the Sexual Liberals and the Attack On](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2943/vol-xxix-no-2-1991-the-sexual-liberals-and-the-attack-on-4072943.webp)

[Vol. Xxix, No. 2 1991] the Sexual Liberals and the Attack On

518 ALBERTA LAW REVIEW [VOL. XXIX, NO. 2 1991] THE SEXUAL LIBERALS AND THE ATTACK ON FEMINISM by Dorchen Leidholdt & Janice G. Raymond, eds, (New York: Pergamon Press, 1990) I. INTRODUCTION Whether it be democracy, aristocracy, oligarchy or monarchy it is still all "cockocracy". Thus the term is coined by Mary Daly in a wild and truly ecstatic flurry of thoughts entitled "Be-Witching: Recalling the Archimagical Powers of Women". 1 The dishevelled tone of Daly's piece, which appears in the final section of the collection, is by no means characteristic of the whole, but the notion of cockocracy, as distinct from patriarchy, is central to the unified purpose of this gathering of feminists. Indeed, the word perhaps ought to have taken on a grander significance in the context of this conference. 2 The ways in which it is a better, more accurate word than patriarchy explain the essential point of all the voices in the anthology. The word patriarchy, when used by feminists, broadly refers to a hierarchical ordering of social, political, economic, familial, and sexual relations where men are on the top and women are on the bottom. Feminists are against it. But there is something about the word patriarchy that is misleading or at least incomplete. It conjures up images of "Father Knows Best", and of the kind of subordination of women that we associate with the fifties and those who cling to the values of the fifties like Marabel Morgan and Anita Bryant The denunciation of patriarchy puts feminists into the ring with right wing ideas of how and why women must be subordinated.