Bisexual Politics: a Superior Form of Feminism?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sovereign Invulnerability: Sexual Politics and the Ontology of Rape

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Sovereign Invulnerability: Sexual Politics and the Ontology of Rape A Dissertation Presented by Jane Clare Jones to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy Stony Brook University December 2016 Copyright by Jane Clare Jones 2016 ii Stony Brook University The Graduate School Jane Clare Jones We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Dissertation Advisor – Dr. Edward S Casey Distinguished Professor, Department of Philosophy Chairperson of Defense – Dr. Megan Craig Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy Internal Reader – Dr. Eva Kittay Distinguished Professor, Department of Philosophy External Reader – Dr. Fiona Vera-Gray Durham Law School, Durham University, UK This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School iii Abstract of the Dissertation Sovereign Invulnerability: Sexual Politics and the Ontology of Rape by Jane Clare Jones Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy Stony Brook University 2016 As Rebecca Whisnant has noted, notions of “national…and…bodily (especially sexual) sovereignty are routinely merged in -

Katy Shannahan Edited

1 Katy Shannahan OUHJ 2013 Submission The Impact of Failed Lesbian Feminist Ideology and Rhetoric Lesbian feminism was a radical feminist separatist movement that developed during the early 1970s with the advent of the second wave of feminism. The politics of this movement called for feminist women to extract themselves from the oppressive system of male supremacy by means of severing all personal and economic relationships with men. Unlike other feminist separatist movements, the politics of lesbian feminism are unique in that their arguments for separatism are linked fundamentally to lesbian identification. Lesbian feminist theory intended to represent the most radical form of the idea that the personal is political by conceptualizing lesbianism as a political choice open to all women.1 At the heart of this solution was a fundamental critique of the institution of heterosexuality as a mechanism for maintaining masculine power. In choosing lesbianism, lesbian feminists asserted that a woman was able to both extricate herself entirely from the system of male supremacy and to fundamentally challenge the patriarchal organization of society.2 In this way they privileged lesbianism as the ultimate expression of feminist political identity because it served as a means of avoiding any personal collaboration with men, who were analyzed as solely male oppressors within the lesbian feminist framework. Political lesbianism as an organized movement within the larger history of mainstream feminism was somewhat short lived, although within its limited lifetime it did produce a large body of impassioned rhetoric to achieve a significant theoretical 1 Radicalesbians, “The Woman-Identified Woman,” (1971). 2 Charlotte Bunch, “Lesbians In Revolt,” The Furies (1972): 8. -

Sexual Liberty and Same-Sex Marriage: an Argument from Bisexuality

University at Buffalo School of Law Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2012 Sexual Liberty and Same-Sex Marriage: An Argument from Bisexuality Michael Boucai University at Buffalo School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Gender and Sexuality Commons Recommended Citation Michael Boucai, Sexual Liberty and Same-Sex Marriage: An Argument from Bisexuality, 49 San Diego L. Rev. 415 (2012). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles/66 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sexual Liberty and Same-Sex Marriage: An Argument from Bisexuality MICHAEL BOUCAI* TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION.........................................................416 II. SEXUAL LIBERTY AND SAME-SEX MARRIAGE .............................. 421 A. A Right To Choose Homosexual Relations and Relationships.........................................421 B. Marriage'sBurden on the Right............................426 1. Disciplineor Punishment?.... 429 2. The Burden's Substance and Magnitude. ................... 432 III. BISEXUALITY AND MARRIAGE.. ......................................... -

Sex, Violence and the Body: the Erotics of Wounding

Sex, Violence and the Body The Erotics of Wounding Edited by Viv Burr and Jeff Hearn PPL-UK_SVB-Burr_FM.qxd 9/24/2008 2:33 PM Page i Sex, Violence and the Body PPL-UK_SVB-Burr_FM.qxd 9/24/2008 2:33 PM Page ii Also by Viv Burr AN INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIONISM GENDER AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY INVITATION TO PERSONAL CONSTRUCT PSYCHOLOGY (with Trevor W. Butt) THE PERSON IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY Also by Jeff Hearn BIRTH AND AFTERBIRTH: A Materialist Account ‘SEX’ AT ‘WORK’: The Power and Paradox of Organisation Sexuality (with Wendy Parkin) THE GENDER OF OPPRESSION: Men, Masculinity and the Critique of Marxism MEN, MASCULINITIES AND SOCIAL THEORY (co-editor with David Morgan) MEN IN THE PUBLIC EYE: The Construction and Deconstruction of Public Men and Public Patriarchies THE VIOLENCES OF MEN: How Men Talk about and How Agencies Respond to Men’s Violence to Women CONSUMING CULTURES: Power and Resistance (co-editor with Sasha Roseneil) TRANSFORMING POLITICS: Power and Resistance (co-editor with Paul Bagguley) GENDER, SEXUALITY AND VIOLENCE IN ORGANIZATIONS: The Unspoken Forces of Organization Violations (with Wendy Parkin) ENDING GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE: A Call for Global Action to Involve Men (with Harry Ferguson et al.) INFORMATION SOCIETY AND THE WORKPLACE: Spaces, Boundaries and Agency (co-editor with Tuula Heiskanen) GENDER AND ORGANISATIONS IN FLUX? (co-editor with Päivi Eriksson et al.) HANDBOOK OF STUDIES ON MEN AND MASCULINITIES (co-editor with Michael Kimmel and R. W. Connell) MEN AND MASCULINITIES IN EUROPE (with Keith Pringle et al.) -

Patricia Highsmith's Queer Disruption: Subverting Gay Tragedy in the 1950S

Patricia Highsmith’s Queer Disruption: Subverting Gay Tragedy in the 1950s By Charlotte Findlay A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Literature Victoria University of Wellington 2019 ii iii Contents Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………..……………..iv Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………v Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..1 1: Rejoicing in Evil: Queer Ambiguity and Amorality in The Talented Mr Ripley …………..…14 2: “Don’t Do That in Public”: Finding Space for Lesbians in The Price of Salt…………………44 Conclusion ...…………………………………………………………………………………….80 Works Cited …………..…………………………………………………………………………83 iv Acknowledgements Thanks to my supervisor, Jane Stafford, for providing always excellent advice, for helping me clarify my ideas by pointing out which bits of my drafts were in fact good, and for making the whole process surprisingly painless. Thanks to Mum and Tony, for keeping me functional for the last few months (I am sure all the salad improved my writing immensely.) And last but not least, thanks to the ladies of 804 for the support, gossip, pad thai, and niche literary humour I doubt anybody else would appreciate. I hope your year has been as good as mine. v Abstract Published in a time when tragedy was pervasive in gay literature, Patricia Highsmith’s 1952 novel The Price of Salt, published later as Carol, was the first lesbian novel with a happy ending. It was unusual for depicting lesbians as sympathetic, ordinary women, whose sexuality did not consign them to a life of misery. The novel criticises how 1950s American society worked to suppress lesbianism and women’s agency. It also refuses to let that suppression succeed by giving its lesbian couple a future together. -

Survival. Activism. Feminism?: Exploring the Lives of Trans* Individuals in Chicago

SURVIVAL. ACTIVISM. FEMINISM? Survival. Activism. Feminism?: Exploring the Lives of Trans* Individuals in Chicago Some radical lesbian feminists, like Sheila Jeffreys (1997, 2003, 2014) argue that trans individuals are destroying feminism by succumbing to the greater forces of the patriarchy and by opting for surgery, thus conforming to normative ideas of sex and gender. Jeffreys is not alone in her views. Janice Raymond (1994, 2015) also maintains that trans individuals work either as male-to-females (MTFs) to uphold stereotypes of femininity and womanhood, or as female-to-males (FTMs) to join the ranks of the oppressors, support the patriarchy, and embrace hegemonic masculinity. Both Jeffreys and Raymond conclude that sex/gender is fixed by genitals at birth and thus deny trans individuals their right to move beyond the identities that they were assigned at birth. Ironically, a paradox is created by these radical lesbians feminist theorists, who deny trans individuals the right to define their own lives and control their own bodies. Such essentialist discourse, however, fails to recognize the oppression, persecution, and violence to which trans individuals are subjected because they do not conform to the sex that they were assigned at birth. Jeffreys (1997) also claims there is an emergency and that the human rights of those who are now identifying as trans are being violated. These critiques are not only troubling to me, as a self-identified lesbian feminist, but are also illogical and transphobic. My research, with trans identified individuals in Chicago, presents a different story and will show another side of the complex relationship between trans and lesbian feminist communities. -

Rethinking Coalitions: Anti-Pornography Feminists, Conservatives, and Relationships Between Collaborative Adversarial Movements

Rethinking Coalitions: Anti-Pornography Feminists, Conservatives, and Relationships between Collaborative Adversarial Movements Nancy Whittier This research was partially supported by the Center for Advanced Study in Behavioral Sciences. The author thanks the following people for their comments: Martha Ackelsberg, Steven Boutcher, Kai Heidemann, Holly McCammon, Ziad Munson, Jo Reger, Marc Steinberg, Kim Voss, the anonymous reviewers for Social Problems, and editor Becky Pettit. A previous version of this paper was presented at the 2011 Annual Meetings of the American Sociological Association. Direct correspondence to Nancy Whittier, 10 Prospect St., Smith College, Northampton MA 01063. Email: [email protected]. 1 Abstract Social movements interact in a wide range of ways, yet we have only a few concepts for thinking about these interactions: coalition, spillover, and opposition. Many social movements interact with each other as neither coalition partners nor opposing movements. In this paper, I argue that we need to think more broadly and precisely about the relationships between movements and suggest a framework for conceptualizing non- coalitional interaction between movements. Although social movements scholars have not theorized such interactions, “strange bedfellows” are not uncommon. They differ from coalitions in form, dynamics, relationship to larger movements, and consequences. I first distinguish types of relationships between movements based on extent of interaction and ideological congruence and describe the relationship between collaborating, ideologically-opposed movements, which I call “collaborative adversarial relationships.” Second, I differentiate among the dimensions along which social movements may interact and outline the range of forms that collaborative adversarial relationships may take. Third, I theorize factors that influence collaborative adversarial relationships’ development over time, the effects on participants and consequences for larger movements, in contrast to coalitions. -

Delayed Critique: on Being Feminist, Time and Time Again

Delayed Critique: On Being Feminist, Time and Time Again In “On Being in Time with Feminism,” Robyn Emma McKenna is a Ph.D. candidate in English and Wiegman (2004) supports my contention that history, Cultural Studies at McMaster University. She is the au- theory, and pedagogy are central to thinking through thor of “‘Freedom to Choose”: Neoliberalism, Femi- the problems internal to feminism when she asks: “… nism, and Childcare in Canada.” what learning will ever be final?” (165) Positioning fem- inism as neither “an antidote to [n]or an ethical stance Abstract toward otherness,” Wiegman argues that “feminism it- In this article, I argue for a systematic critique of trans- self is our most challenging other” (164). I want to take phobia in feminism, advocating for a reconciling of seriously this claim in order to consider how feminism trans and feminist politics in community, pedagogy, is a kind of political intimacy that binds a subject to the and criticism. I claim that this critique is both delayed desire for an “Other-wise” (Thobani 2007). The content and productive. Using the Michigan Womyn’s Music of this “otherwise” is as varied as the projects that femi- Festival as a cultural archive of gender essentialism, I nism is called on to justify. In this paper, I consider the consider how rereading and revising politics might be marginalization of trans-feminism across mainstream, what is “essential” to feminism. lesbian feminist, and academic feminisms. Part of my interest in this analysis is the influence of the temporal Résumé on the way in which certain kinds of feminism are given Dans cet article, je défends l’idée d’une critique systéma- primacy in the representation of feminism. -

Bisexual Crime Victims: Least Visible, Most at Risk

Bisexual Crime Victims: Least Visible, Most at Risk Loree Cook-Daniels and michael munson July 2019 forge-forward.org Thank you OVC ! This training was produced by FORGE under 2016- XV-GX-K015, awarded by the Office for Victims of Crime, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this training are those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. forge-forward.org Welcome & Housekeeping • Take care of yourself • PPTs 3 forge-forward.org FORGE Webinar Leads Loree Cook-Daniels michael munson Policy & Program Director Executive Director 4 forge-forward.org FORGE’s Role in Resource Center • One of eight population groups • FORGE leads the LGBTQ working group • National transgender anti-violence group • Headquartered in Milwaukee, Wisconsin Facebook Twitter Instagram 5 forge-forward.org Agenda • Makeup of the LGBTQ community • Bisexuality: Definitions and Data • Invisibility • Disparities (victimization, health, other) • Best or worst of both worlds? • Service provider barriers • What providers can do to help • Take home messages 6 forge-forward.org Makeup of U.S. LGB Community 7 forge-forward.org 2015 White House Bisexual Community Policy Briefing 8 forge-forward.org Definitions and Data forge-forward.org What about trans people and gender diversity? forge-forward.org Our definition of bisexual A person who is romantically and/or sexually attracted to individuals of their own gender and to individuals of other genders. forge-forward.org “I call myself bisexual because I acknowledge that I have in myself the potential to be attracted – romantically and/or sexually – to people of more than one sex and/or gender, not necessarily at the same time, not necessarily in the same way, and not necessarily to the same degree.” 12 forge-forward.org U.S. -

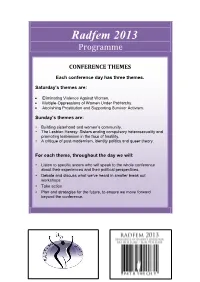

Radfem 2013 Programme

Radfem 2013 Programme CONFERENCE THEMES Each conference day has three themes. Saturday’s themes are: Eliminating Violence Against Women. Multiple-Oppressions of Women Under Patriarchy. Abolishing Prostitution and Supporting Survivor Activism. Sunday’s themes are: Building sisterhood and women’s community. The Lesbian Heresy: Sisters ending compulsory heterosexuality and promoting lesbianism in the face of hostility. A critique of post-modernism, identity politics and queer theory. For each theme, throughout the day we will: Listen to specific sisters who will speak to the whole conference about their experiences and their political perspectives. Debate and discuss what we’ve heard in smaller break out workshops Take action Plan and strategise for the future, to ensure we move forward beyond the conference. Programme Timetable SATURDAY, 8 JUNE TIME / DESCRIPTION ACTIVITY 8.30 – 9.00 Arrive, sign in, optional activities. 9.00 – 9.10 Vita and Lakha Mahila Welcome 9.10 – 9.40 Choose one of the following: Connecting with A. LIVING LIBRARY: TELLING OUR STORIES - RADFEM STORY Sisters BOOKS We all have a herstory and we are all unique with empowering stories to tell about how we are survivors of patriarchy. Come and be a story book and/or listen to other story books about our struggles and our survival. A couple of examples are: “I live in a women’s community” or “I am a political lesbian”. Decide on at least one story before you arrive to this workshop and we’ll help you do the rest. Radfem story books will be told throughout the 2 days and you can tell as many stories as you like to as many women as you like. -

Politics at the Intersection of Sexuality: Examining Political Attitudes and Behaviors of Sexual Minorities in the United States

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2017 Politics at the Intersection of Sexuality: Examining Political Attitudes and Behaviors of Sexual Minorities in the United States Royal Gene Cravens III University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the American Politics Commons Recommended Citation Cravens, Royal Gene III, "Politics at the Intersection of Sexuality: Examining Political Attitudes and Behaviors of Sexual Minorities in the United States. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/4453 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Royal Gene Cravens III entitled "Politics at the Intersection of Sexuality: Examining Political Attitudes and Behaviors of Sexual Minorities in the United States." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Political Science. Anthony J. Nownes, Major Professor -

Discipline Course – I Semester

Traditions in Political Theory: Feminism Discipline Course – I Semester - II Paper : Feminism Lesson Developer: Pushpa Kumari College: Miranda House, University of Delhi 1 Traditions in Political Theory: Feminism Table of Contents Chapter : Traditions in Political Theory: Feminism Introduction Origin and Development First Wave of Feminism Second Wave of Feminism Third Wave of Feminism Approaches in Feminist Studies Liberal Feminism Marxist Feminism Socialist Feminism Radical Feminism Psychoanalytic Feminism Black Feminism Post Modern Feminism Eco Feminism Central Themes in Feminism SexGender Differentiation Nature/Culture The Public/Private Divide Patriarchy and Violence Contemporary Engagements Gendering Political Theory Conclusion Exercise Bibliography Traditions in Political Theory : Feminism 2 Traditions in Political Theory: Feminism The new critical insight such as feminism has expanded the horizon of our understanding in political science. It offers crucial reflections and new ways of looking and making sense of the world around us. It can be observed that such developments have contributed to further evolution of the discipline by making it more inclusive, accommodative and open to new ideas and interpretations. Discourses such as feminism and postmodernism carry great emancipatory potential and have redefined the notion of freedom itself. Whereas feminist endeavours have radically changed the lives of millions of women, postmodernism has unleashed a new spirit to question the conventional ways of understanding and revealing that there can be multiplicity of truths. The dominant universalistic views as projected by white male, Christian, industrial class has been negated. These critical perspectives can lead the effort to dismantle conventional hierarchies and conceptualise a more plural and equal world. Introduction : Women all over the world face inequality, subordination, and secondary status compared to men.