LGBTQ Policy Journal at the John F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STRENGTHENING PARENT and CHILD INTERACTIONS (13-18 Years)

STRENGTHENING PARENT AND CHILD INTERACTIONS (13-18 years) A Blue Dot indicates agencies that are a member of the Maternal Mental Health Collaborative and/or have attended the Postpartum Support International training. Being a parent can be very rewarding, but it can also be very challenging. Because your child is always growing, the information you need to know about parenting and child development changes constantly, too. Learning what behaviors are appropriate for your child’s age and how to handle them can help you better respond to your child. “WHERE CAN I LEARN MORE ABOUT MY CHILD’S DEVELOPMENT?” If you are concerned about your child’s development or need more help, contact your child’s pediatrician, teacher, or school counselor. EMPOWERINGPARENTS.COM Articles from the experts at Empowering Parents to help you manage your teen’s behavior more effectively. Is your adolescent breaking curfew, behaving defiantly or engaging in risky behavior? We offer concrete help for teen behavior problems. www.empoweringparents.com AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS Adolescence can be a rough time for parents. At times, your teen may be a source of frustration and exasperation, not to mention financial stress. But these years also bring many, many moments of joy, pride, laughter and closeness. Find information about privacy, stress, mental health, and other health-related topics. www.healthychildren.org/English/ages-stages/teen INFOABOUTKIDS.ORG This website has links to well-established, trustworthy websites with common parenting concerns related to your child’s body, mind, emotions, and relationships. infoaboutkids.org AHA! PARENTING Provides lots of great, useful advice on how to handle parenting challenges at all ages. -

Trans* Politics and the Feminist Project: Revisiting the Politics of Recognition to Resolve Impasses

Politics and Governance (ISSN: 2183–2463) 2020, Volume 8, Issue 3, Pages 312–320 DOI: 10.17645/pag.v8i3.2825 Article Trans* Politics and the Feminist Project: Revisiting the Politics of Recognition to Resolve Impasses Zara Saeidzadeh * and Sofia Strid Department of Gender Studies, Örebro University, 702 81 Örebro, Sweden; E-Mails: [email protected] (Z.S.), [email protected] (S.S.) * Corresponding author Submitted: 24 January 2020 | Accepted: 7 August 2020 | Published: 18 September 2020 Abstract The debates on, in, and between feminist and trans* movements have been politically intense at best and aggressively hostile at worst. The key contestations have revolved around three issues: First, the question of who constitutes a woman; second, what constitute feminist interests; and third, how trans* politics intersects with feminist politics. Despite decades of debates and scholarship, these impasses remain unbroken. In this article, our aim is to work out a way through these impasses. We argue that all three types of contestations are deeply invested in notions of identity, and therefore dealt with in an identitarian way. This has not been constructive in resolving the antagonistic relationship between the trans* movement and feminism. We aim to disentangle the antagonism within anti-trans* feminist politics on the one hand, and trans* politics’ responses to that antagonism on the other. In so doing, we argue for a politics of status-based recognition (drawing on Fraser, 2000a, 2000b) instead of identity-based recognition, highlighting individuals’ specific needs in soci- ety rather than women’s common interests (drawing on Jónasdóttir, 1991), and conceptualising the intersections of the trans* movement and feminism as mutually shaping rather than as trans* as additive to the feminist project (drawing on Walby, 2007, and Walby, Armstrong, and Strid, 2012). -

Survival. Activism. Feminism?: Exploring the Lives of Trans* Individuals in Chicago

SURVIVAL. ACTIVISM. FEMINISM? Survival. Activism. Feminism?: Exploring the Lives of Trans* Individuals in Chicago Some radical lesbian feminists, like Sheila Jeffreys (1997, 2003, 2014) argue that trans individuals are destroying feminism by succumbing to the greater forces of the patriarchy and by opting for surgery, thus conforming to normative ideas of sex and gender. Jeffreys is not alone in her views. Janice Raymond (1994, 2015) also maintains that trans individuals work either as male-to-females (MTFs) to uphold stereotypes of femininity and womanhood, or as female-to-males (FTMs) to join the ranks of the oppressors, support the patriarchy, and embrace hegemonic masculinity. Both Jeffreys and Raymond conclude that sex/gender is fixed by genitals at birth and thus deny trans individuals their right to move beyond the identities that they were assigned at birth. Ironically, a paradox is created by these radical lesbians feminist theorists, who deny trans individuals the right to define their own lives and control their own bodies. Such essentialist discourse, however, fails to recognize the oppression, persecution, and violence to which trans individuals are subjected because they do not conform to the sex that they were assigned at birth. Jeffreys (1997) also claims there is an emergency and that the human rights of those who are now identifying as trans are being violated. These critiques are not only troubling to me, as a self-identified lesbian feminist, but are also illogical and transphobic. My research, with trans identified individuals in Chicago, presents a different story and will show another side of the complex relationship between trans and lesbian feminist communities. -

View Full Issue As

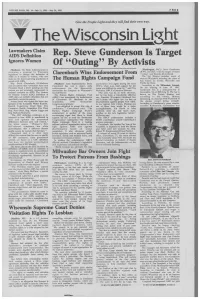

VOLUME FOUR, NO. 14—July 11, 1991—July 24, 1991 FREE Give the People Light and they will find their own way. The Wisconsin Light Lawmakers Claim AIDS Definition Rep. Steve Gunderson Is Target Ignores Women Of "Outing" By Activists [Madison]- The Bush Administration is [Washington, D.C.]- Steve Gunderson reviewing a proposal by Wisconsin (R-WI, 3rd Dist.) was the target of heavy legislators to change the definition of Clarenbach Wins Endorsement From "outing" over the July 4th weekend. AIDS as it relates to women, who now The 3rd District includes much of make up the fastest-growing population of The Human Rights Campaign Fund western Wisconsin including the cities of people with AIDS. Eau Claire, La Crosse, Platteville and Rep. David Clarenbach (D-Madison) [Madison]. State Representative David and Lesbian civil rights during the early Prairie du Chien. and seventeen other lawmakers have sent Clarenbach has won a major, early 1970's, when even mild support for the According to the Milwaukee Journal, President Bush a letter pointing out that endorsement for the Democratic cause was difficult to come by," said Tim On the evening of June 30, 1991, woman are not accurately represented in nomination for Congress in Wisconsin's McFeeley, HRCF's Executive Director. Gunderson was in a restaurant/bar in national statistics on AIDS. The Centers Second District. "Not only was he an early advocate, Alexandria, VA at 808 King St. The bar is for Disease Control (CDC) definition of The Human Rights Campaign Fund but he has been a remarkable effective known as The French Quarter and AIDS does not include infections that are (HRCF) has announced its endorsement one. -

Queer Baroque: Sarduy, Perlongher, Lemebel

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2020 Queer Baroque: Sarduy, Perlongher, Lemebel Huber David Jaramillo Gil The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3862 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] QUEER BAROQUE: SARDUY, PERLONGHER, LEMEBEL by HUBER DAVID JARAMILLO GIL A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Latin American, Iberian and Latino Cultures in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 HUBER DAVID JARAMILLO GIL All Rights Reserved ii Queer Baroque: Sarduy, Perlongher, Lemebel by Huber David Jaramillo Gil This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Latin American, Iberian and Latino Cultures in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Carlos Riobó Chair of Examining Committee Date Carlos Riobó Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Paul Julian Smith Magdalena Perkowska THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Queer Baroque: Sarduy, Perlongher, Lemebel by Huber David Jaramillo Gil Advisor: Carlos Riobó Abstract: This dissertation analyzes the ways in which queer and trans people have been understood through verbal and visual baroque forms of representation in the social and cultural imaginary of Latin America, despite the various structural forces that have attempted to make them invisible and exclude them from the national narrative. -

The Gay Revolution: the Story of the Struggle PDF Book

THE GAY REVOLUTION: THE STORY OF THE STRUGGLE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lillian Faderman | 798 pages | 22 Oct 2015 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9781451694116 | English | New York, United States The Gay Revolution: The Story of the Struggle PDF Book The days of rage become years of struggle. In general, Faderman only pays periodic lip service to trans-led movements in the same cursory way she only pays lip service to radical movements altogether. I know from my own perspective as a life-long lesbian activist, it was my finding these organizations as a teenager that led me to my own activism. But, in a stunning disconnect, lawmakers and the medical doctors who influenced them preferred to insist that people who engaged in such acts comprised a tiny distinct group, different from the rest of humanity. The inspiring history told in this book testifies to the truth of Margaret Mead's famous words: 'Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. We need to be mad. In her prologue, Faderman starts with Johnson and ends with the ceremony to bestow the rank of brigadier general two stars to Army Colonel Tammy Smith. Family Values. It treats so many of the important, but lesser-known moments in this history and brings to life the many players that have made the movement successful as well as highlighting some of the failures in instructive ways. Anisfield- Wolf Book Award. While the history was fascinating, by the time I got near the end I was missing a sense of what it was actually like to live as a gay person in each of the eras she described. -

Safe Zone Training Special

Safe Zone Training School of Social Work Lunch & Learn Series Ellen Belchior Rodrigues, Ph.D. Interim Director - LGBTQ+ Center West Virginia University Ellen Belchior Rodrigues, Ph.D. WVU LGBTQ+ CENTER Outline • Policy • Gender 101: Basic definitions • Specific issues that affect the LGBTQ+ community • Institutional obstacles • Ways to assess your current work and organization • Inclusive language and solutions to positively impact your organizational climate • Learning to be a better ally and advocate Ellen Belchior Rodrigues, Ph.D. WVU LGBTQ+ CENTER Policy Ellen Belchior Rodrigues, Ph.D. WVU LGBTQ+ CENTER Gender 101: Basic Definitions Ellen Belchior Rodrigues, Ph.D. WVU LGBTQ+ CENTER Definitions • “LGBTQ+” is just a start. • Gender: humans have at least 5 chromosomal genders. Other genome and hormonal diversities mean there are many more possibilities for gender than two. Children begin to think about their gender identity around ages 2-4. • Cisgender people identify as the same gender attributed to them at birth. Ellen Belchior Rodrigues, Ph.D. WVU LGBTQ+ CENTER Definitions • Transgender may be an umbrella term to cover people whose gender identity does not match the sex assigned to them at birth. • Nonbinary people do not identify as male or female, finding the gender binary inadequate. • Intersex people are born with variations in gender beyond binary.1.7% of population. Ellen Belchior Rodrigues, Ph.D. WVU LGBTQ+ CENTER Legal recognition of non-binary gender Multiple countries legally recognize non-binary or third gender classifications. Argentina Austria Australia Canada Denmark Germany Iceland India The Netherlands Nepal New Zealand Pakistan Thailand United Kingdom United States Ellen Belchior Rodrigues, Ph.D. -

Whipping Girl

Table of Contents Title Page Dedication Introduction Trans Woman Manifesto PART 1 - Trans/Gender Theory Chapter 1 - Coming to Terms with Transgen- derism and Transsexuality Chapter 2 - Skirt Chasers: Why the Media Depicts the Trans Revolution in ... Trans Woman Archetypes in the Media The Fascination with “Feminization” The Media’s Transgender Gap Feminist Depictions of Trans Women Chapter 3 - Before and After: Class and Body Transformations 3/803 Chapter 4 - Boygasms and Girlgasms: A Frank Discussion About Hormones and ... Chapter 5 - Blind Spots: On Subconscious Sex and Gender Entitlement Chapter 6 - Intrinsic Inclinations: Explaining Gender and Sexual Diversity Reconciling Intrinsic Inclinations with Social Constructs Chapter 7 - Pathological Science: Debunking Sexological and Sociological Models ... Oppositional Sexism and Sex Reassignment Traditional Sexism and Effemimania Critiquing the Critics Moving Beyond Cissexist Models of Transsexuality Chapter 8 - Dismantling Cissexual Privilege Gendering Cissexual Assumption Cissexual Gender Entitlement The Myth of Cissexual Birth Privilege Trans-Facsimilation and Ungendering 4/803 Moving Beyond “Bio Boys” and “Gen- etic Girls” Third-Gendering and Third-Sexing Passing-Centrism Taking One’s Gender for Granted Distinguishing Between Transphobia and Cissexual Privilege Trans-Exclusion Trans-Objectification Trans-Mystification Trans-Interrogation Trans-Erasure Changing Gender Perception, Not Performance Chapter 9 - Ungendering in Art and Academia Capitalizing on Transsexuality and Intersexuality -

Harvey Milk LGBT Democratic Club Questionnaire for Candidates for November 2014

Harvey Milk LGBT Democratic Club Questionnaire for Candidates for November 2014 Dear Candidate, Congratulations on declaring your candidacy. The Harvey Milk LGBT Democratic Club invites you to get to know us better as we seek to learn more about you. As we plan our endorsements for the 2014 election cycle, your participation in our club questionnaire allows our membership to better understand you as a candidate: who you are, what you stand for, and what you plan to accomplish in office. There are two parts to our questionnaire. Part 1 is a series of short-answer questions. We invite you to be descriptive in this section, however, please keep your responses to under 5 sentences. Part 2 is a simple Yes/No questionnaire that covers a broader set of issues than Part 1. You may expand upon Part 2 answers on a separate sheet of paper. Please return the completed questionnaire by 11:59 PM Thursday, August 14th. E-mail all questionnaires to PAC Chair Alex Walker at [email protected]. Please bring at least 5 copies (printed front and back) of your questionnaire to our PAC interviews on Saturday, August 16. If you are unable to do so, please let Alex know ASAP. Please do not print this cover sheet. We will be having our candidate interviews on Saturday, August 16 from 9:30 AM to 4:30 PM at the LGBT Center's Ceremonial Room (1800 Market at Octavia). Alex should be in touch to schedule a 10-minute slot (5 minute speech and the rest for questions and wrap-up). -

Terrorizing Gender: Transgender Visibility and the Surveillance Practices of the U.S

Terrorizing Gender: Transgender Visibility and the Surveillance Practices of the U.S. Security State A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Mia Louisa Fischer IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Mary Douglas Vavrus, Co-Adviser Dr. Jigna Desai, Co-Adviser June 2016 © Mia Louisa Fischer 2016 Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank my family back home in Germany for their unconditional support of my academic endeavors. Thanks and love especially to my Mom who always encouraged me to be creative and queer – far before I knew what that really meant. If I have any talent for teaching it undoubtedly comes from seeing her as a passionate elementary school teacher growing up. I am very thankful that my 92-year-old grandma still gets to see her youngest grandchild graduate and finally get a “real job.” I know it’s taking a big worry off of her. There are already several medical doctors in the family, now you can add a Doctor of Philosophy to the list. I promise I will come home to visit again soon. Thanks also to my sister, Kim who has been there through the ups and downs, and made sure I stayed on track when things were falling apart. To my dad, thank you for encouraging me to follow my dreams even if I chased them some 3,000 miles across the ocean. To my Minneapolis ersatz family, the Kasellas – thank you for giving me a home away from home over the past five years. -

Representing Trans Road Narratives in Mainstream Cinema (1970-2016)

Wish You Were Here: Representing Trans Road Narratives in Mainstream Cinema (1970-2016) by Evelyn Deshane A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2019 © Evelyn Deshane 2019 Examining Committee Membership The following served on the Examining Committee for this thesis. The decision of the Examining Committee is by majority vote. External Examiner Dr. Dan Irving Associate Professor Supervisor Dr. Andrew McMurry Associate Professor Internal-external Member Dr. Kim Nguyen Assistant Professor Internal Members Dr. Gordon Slethaug Adjunct Professor Dr. Victoria Lamont Associate Professor ii Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. iii Abstract When Christine Jorgensen stepped off a plane in New York City from Denmark in 1952, she became one of the first instances of trans celebrity, and her intensely popular story was adapted from an article to a memoir and then a film in 1970. Though not the first trans person recorded in history, Jorgensen's story is crucial in the history of trans representation because her journey embodies the archetypal trans narrative which moves through stages of confusion, discovery, cohesion, and homecoming. This structure was solidified in memoirs of the 1950- 1970s, and grew in popularity alongside the booming film industry in the wake of the Hays Production Code, which finally allowed directors, producers, and writers to depict trans and gender nonconforming characters and their stories on-screen. -

Transgender History / by Susan Stryker

u.s. $12.95 gay/Lesbian studies Craving a smart and Comprehensive approaCh to transgender history historiCaL and Current topiCs in feminism? SEAL Studies Seal Studies helps you hone your analytical skills, susan stryker get informed, and have fun while you’re at it! transgender history HERE’S WHAT YOU’LL GET: • COVERAGE OF THE TOPIC IN ENGAGING AND AccESSIBLE LANGUAGE • PhOTOS, ILLUSTRATIONS, AND SIDEBARS • READERS’ gUIDES THAT PROMOTE CRITICAL ANALYSIS • EXTENSIVE BIBLIOGRAPHIES TO POINT YOU TO ADDITIONAL RESOURCES Transgender History covers American transgender history from the mid-twentieth century to today. From the transsexual and transvestite communities in the years following World War II to trans radicalism and social change in the ’60s and ’70s to the gender issues witnessed throughout the ’90s and ’00s, this introductory text will give you a foundation for understanding the developments, changes, strides, and setbacks of trans studies and the trans community in the United States. “A lively introduction to transgender history and activism in the U.S. Highly readable and highly recommended.” SUSAN —joanne meyerowitz, professor of history and american studies, yale University, and author of How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality In The United States “A powerful combination of lucid prose and theoretical sophistication . Readers STRYKER who have no or little knowledge of transgender issues will come away with the foundation they need, while those already in the field will find much to think about.” —paisley cUrrah, political