History of North Dakota Chapter 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise and Fall of the Lake Pepin “Half-Breed Tract” Allison C. Bender

Valuable People: The Rise and Fall of the Lake Pepin “Half-Breed Tract” Allison C. Bender History 489: Research Seminar Fall Term 2016 Contents Abstract………...……….……………………………...…………………………………………iii Introduction and Historiography…………………………………………………………………..1 Race as a Social Construct.....……………………………………………………………………..5 Treaty of Prairie du Chien 1825…………………………………………………….......................7 Understanding the Treaty of Prairie du Chien 1830......................................................................10 The Lake Pepin “Half-Breed” Tract..............................................................................................16 Franklin Steele and the Fort Snelling Internment Camp...............................................................18 Call for Further Research………………………………………………………………………...22 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………….24 Works Cited.………………………………………………………………….………………….27 ii Abstract This paper focuses on the Dakota nation during the early nineteenth century while discussing the various tribes within the Midwest during that time. These tribes include the Ojibwe, confederated Sacs and Foxes, Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Ioway, Ottowa, and Potawatomi. As intertribal warfare disrupted the peace between these tribes, it also disrupted the plans of many European settlers who had wanted to live, farm, hunt, mineral mine, and trade in the Midwest. One can see evidence of this disruption by visiting treaties from the early nineteenth century as well as accounts from various Indian Agents from this time. Several treaties -

The Practical A-Z Guide to Going on Safari.Pages

The Practical A-Z Guide to Going on Safari Everything You Need to Know Copyright © 2016-2017 Michaël Theys. http://africafreak.com All rights are reserved. You may not sell, or reprint any part of this document without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review. WARNING: This eBook is for your personal use only. You may NOT sell this intellectual property in any way. The Practical Guide to Going on Safari What is Safari? 5 Who is Michael Theys? 6 The Practical Guide to Going on Safari 8 A = Accessories 8 B = Binoculars 9 B = Books 10 B = Baboon Protection 12 B = Big Five 13 C = Clothing 14 D = Debit and Credit Cards 15 E = Electricity Plug Converters 16 E = Emergency Toilet Paper 16 F = Food 17 G = Great Wildebeest Migration 18 H = Hat 19 H = Handwash 20 I = Insect Repellent 20 I = Insurance Certificate 21 J = Jambo 21 K = Kilimanjaro 23 L = Leave the Fashion at Home 24 L = Luggage 24 M = Malaria Medication 25 N = Neutral Colours 26 O = Ornithology 27 P = Patience 28 P = Packing Light 28 P = Passport 29 P = Photography 29 Q = Quenching Your Thirst 31 R = Random Safari Activities 31 R = Respect the Environment 32 S = Shop 33 S = Shoes 34 S = Sun Protection 35 T = Torch 36 Find us on Facebook AfricaFreak.com !3 The Practical Guide to Going on Safari T = Tipping 36 U = U.S. Dollars in Cash 37 V = Vaccinations 37 V = Visas for Travel 37 W = Walking Safaris 38 W = Wifi (or lack of) 39 X = X-Rated Wildlife Situations 39 Y = Yellow Fever Certificate 40 Z = Zzzz.. -

Thursday, June 15, 2017 Thursday, June 15, 2017 2016 Integrated Report - Walsh County

Thursday, June 15, 2017 Thursday, June 15, 2017 2016 Integrated Report - Walsh County Thursday, June 15, 2017 Cart Creek Waterbody ID Waterbody Type Waterbody Description Date TMDL Completed ND-09020310-044-S_00 RIVER Cart Creek from its confluence with A tributary 2 miles east of Mountain, ND downstream to its confluence with North Branch Park River Size Units Beneficial Use Impaired Beneficial Use Status Cause of Impairment TMDL Priority 36.32 MILES Fish and Other Aquatic Biota Not Supporting Fishes Bioassessments L ND-09020310-044-S_00 RIVER Cart Creek from its confluence with A tributary 2 miles east of Mountain, ND downstream to its confluence with North Branch Park River Size Units Beneficial Use Impaired Beneficial Use Status Cause of Impairment TMDL Priority 36.32 MILES Fish and Other Aquatic Biota Not Supporting Benthic-Macroinvertebrate Bioassessments L Forest River Waterbody ID Waterbody Type Waterbody Description Date TMDL Completed ND-09020308-001-S_00 RIVER Forest River from Lake Ardoch, downstream to its confluence with the Red River Of The North. Size Units Beneficial Use Impaired Beneficial Use Status Cause of Impairment TMDL Priority 15.49 MILES Fish and Other Aquatic Biota Not Supporting Benthic-Macroinvertebrate Bioassessments L ND-09020308-001-S_00 RIVER Forest River from Lake Ardoch, downstream to its confluence with the Red River Of The North. Size Units Beneficial Use Impaired Beneficial Use Status Cause of Impairment TMDL Priority 15.49 MILES Fish and Other Aquatic Biota Not Supporting Fishes Bioassessments L ND-09020308-001-S_00 RIVER Forest River from Lake Ardoch, downstream to its confluence with the Red River Of The North. -

Native American Context Statement and Reconnaissance Level Survey Supplement

NATIVE AMERICAN CONTEXT STATEMENT AND RECONNAISSANCE LEVEL SURVEY SUPPLEMENT Prepared for The City of Minneapolis Department of Community Planning & Economic Development Prepared by Two Pines Resource Group, LLC FINAL July 2016 Cover Image Indian Tepees on the Site of Bridge Square with the John H. Stevens House, 1852 Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society (Neg. No. 583) Minneapolis Pow Wow, 1951 Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society (Neg. No. 35609) Minneapolis American Indian Center 1530 E Franklin Avenue NATIVE AMERICAN CONTEXT STATEMENT AND RECONNAISSANCE LEVEL SURVEY SUPPLEMENT Prepared for City of Minneapolis Department of Community Planning and Economic Development 250 South 4th Street Room 300, Public Service Center Minneapolis, MN 55415 Prepared by Eva B. Terrell, M.A. and Michelle M. Terrell, Ph.D., RPA Two Pines Resource Group, LLC 17711 260th Street Shafer, MN 55074 FINAL July 2016 MINNEAPOLIS NATIVE AMERICAN CONTEXT STATEMENT AND RECONNAISSANCE LEVEL SURVEY SUPPLEMENT This project is funded by the City of Minneapolis and with Federal funds from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. The contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior. This program receives Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, or disability in its federally assisted programs. -

Transportation on the Minneapolis Riverfront

RAPIDS, REINS, RAILS: TRANSPORTATION ON THE MINNEAPOLIS RIVERFRONT Mississippi River near Stone Arch Bridge, July 1, 1925 Minnesota Historical Society Collections Prepared by Prepared for The Saint Anthony Falls Marjorie Pearson, Ph.D. Heritage Board Principal Investigator Minnesota Historical Society Penny A. Petersen 704 South Second Street Researcher Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 Hess, Roise and Company 100 North First Street Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 May 2009 612-338-1987 Table of Contents PROJECT BACKGROUND AND METHODOLOGY ................................................................................. 1 RAPID, REINS, RAILS: A SUMMARY OF RIVERFRONT TRANSPORTATION ......................................... 3 THE RAPIDS: WATER TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS .............................................. 8 THE REINS: ANIMAL-POWERED TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ............................ 25 THE RAILS: RAILROADS BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ..................................................................... 42 The Early Period of Railroads—1850 to 1880 ......................................................................... 42 The First Railroad: the Saint Paul and Pacific ...................................................................... 44 Minnesota Central, later the Chicago, Milwaukee and Saint Paul Railroad (CM and StP), also called The Milwaukee Road .......................................................................................... 55 Minneapolis and Saint Louis Railway ................................................................................. -

Chapter 1: Introduction and Overview

PROJECT 6 – ALL-SEASON ROAD ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Chapter 1: Introduction and Overview PROJECT 6 – ALL-SEASON ROAD ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW ......................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 The Proponent – Manitoba Infrastructure ...................................................................... 1-1 1.1.1 Contact Information ........................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.2 Legal Entity .......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.3 Corporate and Management Structures ............................................................. 1-1 1.1.4 Corporate Policy Implementation ...................................................................... 1-2 1.1.5 Document Preparation ....................................................................................... 1-2 1.2 Project Overview .............................................................................................................. 1-3 1.2.1 Project Components ......................................................................................... 1-11 1.2.2 Project Phases and Scheduling ......................................................................... 1-11 1.2.3 The East Side Transportation Initiative ............................................................. 1-14 1.3 Project Location ............................................................................................................ -

Copyrighted Material Not for Distribution Fidler in Context

TABLE OF CONTENTS acknowledgements vii introduction Fidler in Context 1 first journal From York Factory to Buckingham House 43 second journal From Buckingham House to the Rocky Mountains 95 notes to the first journal 151 notes to the second journal 241 sources and references 321 index 351 COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION FIDLER IN CONTEXT In July 1792 Peter Fidler, a young surveyor for the Hudson’s Bay Company, set out from York Factory to the company’s new outpost high on the North Saskatchewan River. He spent the winter of 1792‐93 with a group of Piikani hunting buffalo in the foothills SW of Calgary. These were remarkable journeys. The river brigade travelled more than 2000 km in 80 days, hauling heavy loads, moving upstream almost all the way. With the Piikani, Fidler witnessed hunts at sites that archaeologists have since studied intensively. On both trips his assignment was to map the fur-trade route from Hudson Bay to the Rocky Mountains. Fidler kept two journals, one for the river trip and one for his circuit with the Piikani. The freshness and immediacy of these journals are a great part of their appeal. They are filled with descriptions of regional landscapes, hunting and trading, Native and fur-trade cultures, all of them reflecting a young man’s sense of adventure as he crossed the continent. But there is noth- ing naive or spontaneous about these remarks. The journals are transcripts of his route survey, the first stages of a map to be sent to the company’s head office in London. -

NWC-3361 Cover Layout2.Qx

2 0 0 1 A N N U A L R E P O R T vision growth value N O R T H W E S T C O M P A N Y F U N D 2 0 0 1 A N N U A L R E P O R T 2001 financial highlights in thousands of Canadian dollars 2001 2000 1999 Fiscal Year 52 weeks 52 weeks 52 weeks Results for the Year Sales and other revenue $ 704,043 $ 659,032 $ 626,469 Trading profit (earnings before interest, income taxes and amortization) 70,535 63,886 59,956 Earnings 29,015 28,134 27,957 Pre-tax cash flow 56,957 48,844 46,747 Financial Position Total assets $ 432,033 $ 415,965 $ 387,537 Total debt 151,581 175,792 171,475 Total equity 219,524 190,973 169,905 Per Unit ($) Earnings for the year $ 1.95 $ 1.89 $ 1.86 Pre-tax cash flow 3.82 3.28 3.12 Cash distributions paid during the year 1.455 1.44 1.44 Equity 13.61 13.00 11.33 Market price – January 31 17.20 13.00 12.00 – high 17.50 13.00 15.95 – low 12.75 9.80 11.25 Financial Ratios Debt to equity 0.69:1 0.92:1 1.01:1 Return on net assets* 12.7% 11.5% 11.6% Return on average equity 14.9% 15.2% 16.8% *Earnings before interest and income taxes as a percent of average net assets employed All currency figures in this report are in Canadian dollars, unless otherwise noted. -

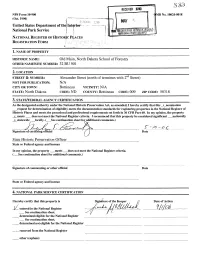

NATIONAL REGISTER of HISTORIC P$ACES REGISTRATION FORM I = R

NFS Form 10-900 ( MB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of thc Interior- National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC P$ACES REGISTRATION FORM I = r - 1. NAME OF PROPERTY HISTORIC NAME: Old Main, North Dakota School of Forestry OTHER NAME/SITE NUMBER: 32 BU 501 2. LOCATION STREET & NUMBER: Alexander Street (north of terminus with 2nd Street) NOT FOR PUBLICATION: N/A CITY OR TOWN: Bottineau VICINITY: N/A STATE: North Dakota CODE.-ND COUNTY: Bottineau CODE: 009 ZIP CODE: 58318 3. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this _x_nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _x_meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant __ nationally _x_statewide __ locally. ( __ See continuation sheet for additional comments.) _ Signature of certifying official Date State Historic Preservation Officer State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property __meets __does not meet the National Register criteria. (__See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4. NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CERTIFICATION I hereby certify that this property is Signature of the Keeper Date of Action entered in the National Register __ See continuation sheet. determined eligible for the National Register __ See continuation sheet. -

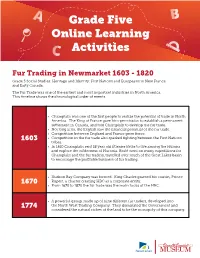

Grade Five Online Learning Activities

Grade Five Online Learning Activities Fur Trading in Newmarket 1603 - 1820 Grade 5 Social Studies: Heritage and Identity: First Nations and Europeans in New France and Early Canada. The Fur Trade was one of the earliest and most important industries in North America. This timeline shows the chronological order of events. • Champlain was one of the first people to realize the potential of trade in North America. The King of France gave him permission to establish a permanent settlement in Canada, and told Champlain to develop the fur trade. • Not long after, the English saw the financial potential of the fur trade. • Competition between England and France grew fierce. 1603 • Competition in the fur trade also sparked fighting between the First Nations tribes. • In 1610 Champlain sent 18 year old Étienne Brulé to live among the Hurons and explore the wilderness of Huronia. Brulé went on many expeditions for Champlain and the fur traders, travelled over much of the Great Lakes basin to encourage the profitable business of fur trading. • Hudson Bay Company was formed. King Charles granted his cousin, Prince 1670 Rupert, a charter creating HBC as a corporate entity. • From 1670 to 1870 the fur trade was the main focus of the HBC. • A powerful group, made up of nine different fur traders, developed into 1774 the North West Trading Company. They dominated the Government and considered the natural riches of the land to be the monopoly of this company. Grade Five Online Learning Activities Fur Trading in Newmarket 1603 - 1820 • Competition and jealousy raged between the North West Company and the 1793 Hudson Bay Company. -

CONTEXT DOCUMENT on the FUR TRADE of NORTHEASTERN

CONTEXT DOCUMENT on the FUR TRADE OF NORTHEASTERN NORTH DAKOTA (Ecozone #16) 1738-1861 by Lauren W. Ritterbush April 1991 FUR TRADE IN NORTHEASTERN NORTH DAKOTA {ECOZONE #16). 1738-1861 The fur trade was the commercia1l medium through which the earliest Euroamerican intrusions into North America were made. Tl;ns world wide enterprise led to the first encounters between Euroamericar:is and Native Americans. These contacts led to the opening of l1ndian lands to Euroamericans and associated developments. This is especial,ly true for the h,istory of North Dakota. It was a fur trader, Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, Sieur de la Ve--endrye, and his men that were the first Euroamericans to set foot in 1738 on the lar;ids later designated part of the state of North Dakota. Others followed in the latter part of the ,eighteenth and first half of the nineteenth century. The documents these fur traders left behind are the earliest knowr:i written records pertaining to the region. These ,records tell much about the ear,ly commerce of the region that tied it to world markets, about the indigenous popu,lations living in the area at the time, and the environment of the region before major changes caused by overhunting, agriculture, and urban development were made. Trade along the lower Red River, as well as along, the Misso1.:1ri River, was the first organized E uroamerican commerce within the area that became North Dakota. Fortunately, a fair number of written documents pertainir.1g to the fur trade of northeastern North 0akota have been located and preserved for study. -

Fishing the Red River of the North

FISHING THE RED RIVER OF THE NORTH The Red River boasts more than 70 species of fish. Channel catfish in the Red River can attain weights of more than 30 pounds, walleye as big as 13 pounds, and northern pike can grow as long as 45 inches. Includes access maps, fishing tips, local tourism contacts and more. TABLE OF CONTENTS YOUR GUIDE TO FISHING THE RED RIVER OF THE NORTH 3 FISHERIES MANAGEMENT 4 RIVER STEWARDSHIP 4 FISH OF THE RED RIVER 5 PUBLIC ACCESS MAP 6 PUBLIC ACCESS CHART 7 AREA MAPS 8 FISHING THE RED 9 TIP AND RAP 9 EATING FISH FROM THE RED RIVER 11 CATCH-AND-RELEASE 11 FISH RECIPES 11 LOCAL TOURISM CONTACTS 12 BE AWARE OF THE DANGERS OF DAMS 12 ©2017, State of Minnesota, Department of Natural Resources FAW-471-17 The Minnesota DNR prohibits discrimination in its programs and services based on race, color, creed, religion, national origin, sex, public assistance status, age, sexual orientation or disability. Persons with disabilities may request reasonable modifications to access or participate in DNR programs and services by contacting the DNR ADA Title II Coordinator at [email protected] or 651-259-5488. Discrimination inquiries should be sent to Minnesota DNR, 500 Lafayette Road, St. Paul, MN 55155-4049; or Office of Civil Rights, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1849 C. Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20240. This brochure was produced by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Division of Fish and Wildlife with technical assistance provided by the North Dakota Department of Game and Fish.