Download Complete [PDF]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (APO)

E-Book - 22. Checklist - Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (A.P.O) By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 22. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 8th May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 27 Nos. Date/Year Details of Issue 1 2 1971 - 1980 1 01/12/1954 International Control Commission - Indo-China 2 15/01/1962 United Nations Force - Congo 3 15/01/1965 United Nations Emergency Force - Gaza 4 15/01/1965 International Control Commission - Indo-China 5 02/10/1968 International Control Commission - Indo-China 6 15.01.1971 Army Day 7 01.04.1971 Air Force Day 8 01.04.1971 Army Educational Corps 9 04.12.1972 Navy Day 10 15.10.1973 The Corps of Electrical and Mechanical Engineers 11 15.10.1973 Zojila Day, 7th Light Cavalary 12 08.12.1973 Army Service Corps 13 28.01.1974 Institution of Military Engineers, Corps of Engineers Day 14 16.05.1974 Directorate General Armed Forces Medical Services 15 15.01.1975 Armed Forces School of Nursing 03.11.1976 Winners of PVC-1 : Maj. Somnath Sharma, PVC (1923-1947), 4th Bn. The Kumaon 16 Regiment 17 18.07.1977 Winners of PVC-2: CHM Piru Singh, PVC (1916 - 1948), 6th Bn, The Rajputana Rifles. 18 20.10.1977 Battle Honours of The Madras Sappers Head Quarters Madras Engineer Group & Centre 19 21.11.1977 The Parachute Regiment 20 06.02.1978 Winners of PVC-3: Nk. -

SABHA & Armed Forces

WHAT THEY SAY sabha & ARMED FORCES The Sabha has forged a unique function is witnessed by men from year, the Republic day celebrations partnership with the armed forces. the forces in this area alongwith are devoted to the “Wounded It is for the first time that a civil their families. The army band plays Warrior”. Army men incapacitated society engaged in furthering fine on the occasion. The goC presides to varying degrees of disability arts has joined hands with the over the function. while defending the nation are armed forces to celebrate the On the 26th January each honoured on the occasion. Independence and Republic day each year for the welfare of the armed forces. The general Officer Commanding (Maharashtra, gujarat and goa) headquartered at Mumbai represents the Armed forces in the celebrations. The Independence Day is devoted to “Martyrs”. Families of the men in uniform who sacrificed their lives in the cause of the nation and hailing from this command area are honoured and given a solatium of Rs. 2,00,000/- each and mementos worth Rs. 50,000/-. The § 108 § Shanmukhananda culture redefined2A-Original.indd 108 02/05/19 9:03 AM IT0NDIA A 7 The Sabha celebrated the completion of the 70th year of Indian independence and the commencement of the 71st anniversary on 15th August 2017. It was for the first time in the history of the Sabha that the Indian army actively participated in the celebrations. Lt. gen. Vishwambhar Singh, AVSM, VSM, general Officer Commanding, Maharashtra, gujarat and goa Area presided over the function. The programme was marked by patriotic fervor, emotions and a never before experienced tribute for the martyrs. -

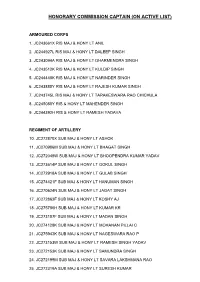

Honorary Commission Captain (On Active List)

HONORARY COMMISSION CAPTAIN (ON ACTIVE LIST) ARMOURED CORPS 1. JC243661X RIS MAJ & HONY LT ANIL 2. JC244927L RIS MAJ & HONY LT DALEEP SINGH 3. JC243094A RIS MAJ & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH 4. JC243512K RIS MAJ & HONY LT KULDIP SINGH 5. JC244448K RIS MAJ & HONY LT NARINDER SINGH 6. JC243880Y RIS MAJ & HONY LT RAJESH KUMAR SINGH 7. JC243745L RIS MAJ & HONY LT TARAKESWARA RAO CHICHULA 8. JC245080Y RIS & HONY LT MAHENDER SINGH 9. JC244392H RIS & HONY LT RAMESH YADAVA REGIMENT OF ARTILLERY 10. JC272870X SUB MAJ & HONY LT ASHOK 11. JC270906M SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHAGAT SINGH 12. JC272049W SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHOOPENDRA KUMAR YADAV 13. JC273614P SUB MAJ & HONY LT GOKUL SINGH 14. JC272918A SUB MAJ & HONY LT GULAB SINGH 15. JC274421F SUB MAJ & HONY LT HANUMAN SINGH 16. JC270624N SUB MAJ & HONY LT JAGAT SINGH 17. JC272863F SUB MAJ & HONY LT KOSHY AJ 18. JC275786H SUB MAJ & HONY LT KUMAR KR 19. JC273107F SUB MAJ & HONY LT MADAN SINGH 20. JC274128K SUB MAJ & HONY LT MOHANAN PILLAI C 21. JC275943K SUB MAJ & HONY LT NAGESWARA RAO P 22. JC273153W SUB MAJ & HONY LT RAMESH SINGH YADAV 23. JC272153K SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAMUNDRA SINGH 24. JC272199M SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAVARA LAKSHMANA RAO 25. JC272319A SUB MAJ & HONY LT SURESH KUMAR 26. JC273919P SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 27. JC271942K SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 28. JC279081N SUB & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH RATHORE 29. JC277689K SUB & HONY LT KAMBALA SREENIVASULU 30. JC277386P SUB & HONY LT PURUSHOTTAM PANDEY 31. JC279539M SUB & HONY LT RAMESH KUMAR SUBUDHI 32. -

Answered On:04.05.2000 Army Regiments Rasa Singh Rawat

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA DEFENCE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:5981 ANSWERED ON:04.05.2000 ARMY REGIMENTS RASA SINGH RAWAT Will the Minister of DEFENCE be pleased to state: (a) the names of different regiments in Indian Army as on date; (b) whether only the people of a particular caste and class are recruited in a particular regiment; (c) whether the Government propose to give equal recruitment opportunities to the people of all the communities; (d) if so, the reason for not recruiting the people of other communities in a regiment named under a particular community; (e) whether the Government have received any complaints in this regard; (f) if so, the details thereof and the steps being taken by the Government to remove this imbalance; (g) whether the Government have also received any proposals to raise some new regiments; (h) if so, the details thereof and the reaction of the Government thereto; (i) whether in the past, there had been a regiment named as `Azmer Regiment`; and (j) if so, the reasons for disbanding the same? Answer MINISTER OF DEFENCE (SHRI GEORGE FERNANDES) (a) A list of names of 29 regiments of the Indian Army is enclosed. (b) No, Sir. The regimental vacancies are filled up based on the class composition of the regiment which need not be confined to a particular caste or community. Besides, the class composition of the regiment does not include officers, clerks, cooks, washermen, barbars, safaiwalas and other tradesmen who are recruited on all-India all class vacancies. (c) & (d): Recruitment to the Army is open to all Indian nationals irrespective of class, caste, creed, religion or region subject to educational qualification and physical fitness. -

Answered On:18.12.2003 Opening of Army Colleges Institutes Schools Amir Alam Khan;Ratilal Kalidas Varma

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA DEFENCE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:2514 ANSWERED ON:18.12.2003 OPENING OF ARMY COLLEGES INSTITUTES SCHOOLS AMIR ALAM KHAN;RATILAL KALIDAS VARMA Will the Minister of DEFENCE be pleased to state: (a) the number of Army Colleges, Institutes and Schools existed in country, State-wise; (b) whether there is any proposal to open more Army Colleges, Institutes and Schools in the country; (c) if so, the details thereof, State-wise; and (d) if not, the reasons therefor? Answer MINISTER OF DEFENCE (SHRI GEORGE FERNANDES) (a) List of Army Colleges, Institutes or Schools as existing in the country, State-wise, is attached. (b) & (c): At present there is no proposal to open additional Army Colleges, Institutes or Schools in the country. (d) The training needs of the Army are adequately being met by the presently existing training establishments. ANNEXURE `A`R EFERRED TO IN THE REPLY GIVEN IN PART (a) OF LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 2514 FOR 18.12.2003 LIST OF ARMY COLLEGES, INSTITUTES OR SCHOOLS CATEGORY `A` ESTABLISHMENTS (Catering mainly to officers) Sr No. State Name of Establishment City 1. Andhra Pradesh College of Defence Management Secunderabad 2. Andhra Pradesh Military College of Electronics Secunderabad and Mechanical Engineering 3. Andhra Pradesh Simulator Development Division Trimulgherry CO/ MCEME 4. Gujarat Electrical and Mechanical Baroda Engineering School 5. Himachal Pradesh Military School Chail 6. J&K High Altitude Warfare School Gulmarg 7 Jharkhand Junior Leader`s Academy Ramgarh 8. Karnataka Junior Leaders Wing, Inf School Belgaum 9. Karnataka Army Service Corps Centre Bangalore and School 10. -

Sainik 16-28 February Covers

In This Issue Since 1909 BIRTH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATIONS Beating the Retreat 2018 4 (Initially published as FAUJI AKHBAR) Vol. 65 q No 4 27 Magha - 9 Phalguna, 1939 (Saka) 16-28 February 2018 The journal of India’s Armed Forces published every fortnight in thirteen languages including Hindi & English on behalf of Ministry of Defence. It is not necessarily an organ for the expression of the Government’s defence policy. The published items represent the views of respective writers and correspondents. Editor-in-Chief Hasibur Rahman Senior Editor Ms Ruby T Sharma Raksha Mantri felicitates 6 Raksha Mantri visits INS Editor Ehsan Khusro winners of Republic… Parundu and INS… 8 Sub Editor Sub Maj KC Sahu Coordination Kunal Kumar Business Manager Rajpal Our Correspondents DELHI: Col Aman Anand; Capt DK Sharma VSM; Wg Cdr Anupam Banerjee; Manoj Tuli; Nampibou Marinmai; Ved Pal; Divyanshu Kumar; Photo Editor: K Ramesh; ALLAHABAD: Gp Capt BB Pande; BENGALURU: Guruprasad HL; CHANDIGARH: Anil Gaur; CHENNAI: T Shanmugam; GANDHINAGAR: Wg Cdr Abhishek Matiman; GUWAHATI: Lt Col Suneet Newton; IMPHAL: Lt Col Ajay Kumar Sharma; JALANDHAR : Anil Gaur; JAMMU: Col Lt Col Devender Anand; JAIPUR: Lt Col Manish Ojha; KOCHI: Cdr Sridhar E Warrier ; KOHIMA: Col Chiranjeet Konwer; KOLKATA: 11 GOC Dakshin Bharat Area visits… Wg Cdr SS Birdi; Dipannita Dhar; LUCKNOW: Ms Gargi Malik Sinha; MUMBAI: Cdr Visit of Raksha Mantri to Rahul Sinha; Narendra Vispute; NAGPUR: Wg Cdr Samir S Gangakhedkar; PALAM: 14 Third Scorpene Submarine… Wg Cdr AR Giri;PUNE: Mahesh Iyengar; SECUNDERABAD: G Surendra Babu; 16 NCC cadets and students visit… 14 Corps Zone 10 Wg Cdr Ratnakar Singh; Col Rajesh Kalia; Lt SHILLONG; SRINAGAR: TEZPUR: 17 Passing Out Parade of Military… Col Sombit Ghosh; THIRUVANANTHAPURAM: Ms Dhanya Sanal K; UDHAMPUR: Col NN Joshi; VISAKHAPATNAM: Cdr CG Raju. -

Martial Races' and War Time Unit Deployment in the Indian Army

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2019 Who Does The Dying?: 'Martial Races' and War Time Unit Deployment in the Indian Army Ammon Frederick Harteis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Comparative Politics Commons Recommended Citation Frederick Harteis, Ammon, "Who Does The Dying?: 'Martial Races' and War Time Unit Deployment in the Indian Army" (2019). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1417. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1417 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Who Does The Dying? ‘Martial Races’ and War Time Unit Deployment in the Indian Army Ammon Frederick Harteis Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori Frederick Harteis 1 Abstract During the Second World War, the Indian Army held back units and soldiers that were not from the so-called “martial races” from frontline combat service. The British “martial races” theory held that only a small number of communities in India were fit for military service and people from all “non-martial” communities should be excluded from the Army. Has the Indian Army, after gaining independence from British leadership, contended the Second World War practice of deploying “martial” units in combat while assigning “non-martial” units to non- combat roles? It has been conclusively demonstrated that “martial race” groups have contended to be overrepresented in the post-colonial Indian Army. -

S. No. Rank & Name Service Mahavir Chakra Ic-64405M

S. NO. SERVICE RANK & NAME MAHAVIR CHAKRA 1. IC-64405M COLONEL BIKUMALLA SANTOSH BABU ARMY 16 TH BATTALION THE BIHAR REGIMENT (POSTHUMOUS) KIRTI CHAKRA 1. JC-413798Y SUBEDAR SANJIV KUMAR ARMY 4TH BATTALION THE PARACHUTE REGIMENT (SPECIAL FORCES) (POSTHUMOUS) 2. SHRI PINTU KUMAR SINGH, INSPECTOR /GD, MHA CRPF (POSTHUMOUS) 3. SHRI SHYAM NARAIN SINGH YADAVA, HEAD MHA CONSTABLE/GD, CRPF (POSTHUMOUS) 4. SHRI VINOD KUMAR, CONSTABLE, CRPF (POSTHUMOUS) MHA 5. SHRI RAHUL MATHUR, DEPUTY COMMANDANT, CRPF MHA VIR CHAKRA 1. JC-561645F NAIB SUBEDAR NUDURAM SOREN ARMY 16 TH BATTALION THE BIHAR REGIMENT (POSTHUMOUS) 2. 15139118Y HAVILDAR K PALANI ARMY 81 FIELD REGIMENT (POSTHUMOUS) 3. 15143643M HAVILDAR TEJINDER SINGH ARMY 3 MEDIUM REGIMENT 4. 15439373K NAIK DEEPAK SINGH ARMY THE ARMY MEDICAL CORPS, 16 TH BATTALION THE BIHAR REGIMENT (POSTHUMOUS) S. NO. SERVICE RANK & NAME 5. 2516683X SEPOY GURTEJ SINGH ARMY 3RD BATTALION THE PUNJAB REGIMENT (POSTHUMOUS) SHAURYA CHAKRA 1. IC-76429H MAJOR ANUJ SOOD ARMY BRIGADE OF THE GUARDS, 21 ST BATTALION THE RASHTRIYA RIFLES (POSTHUMOUS) 2. G/5022546P RIFLEMAN PRANAB JYOTI DAS ARMY 6TH BATTALION THE ASSAM RIFLES 3. 13631414L PARATROOPER SONAM TSHERING TAMANG ARMY 4TH BATTALION THE PARACHUTE REGIMENT (SPECIAL FORCES) 4. SHRI ARSHAD KHAN, INSPECTOR, J&K MHA POLICE (POSTHUMOUS) 5. SHRI GH MUSTAFA BARAH, SGCT, J&K MHA POLICE (POSTHUMOUS) 6. SHRI NASEER AHMAD KOLIE, SGCT, CONSTABLE, J&K MHA POLICE (POSTHUMOUS) 7. SHRI BILAL AHMAD MAGRAY, SPECIAL POLICE OFFICER, MHA J&K POLICE (POSTHUMOUS) BAR TO SENA MEDAL (GALLANTRY) 1. IC-65402L COLONEL ASHUTOSH SHARMA, BAR TO SENA ARMY MEDAL (POSTHUMOUS) BRIGADE OF THE GUARDS, 21 ST BATTALION THE RASHTRIYA RIFLES 2. -

S. No. RANK and NAME SERVICE KIRTI CHAKRA SHRI ABDUL

S. No. RANK AND NAME SERVICE KIRTI CHAKRA 1. SHRI ABDUL RASHID KALAS, HEAD CONSTABLE, JAMMU AND KASHMIR MHA POLICE (POSTHUMOUSLY) SHAURYA CHAKRA 1. IC-68482Y LIEUTENANT COLONEL KRISHAN SINGH RAWAT, SENA MEDAL ARMY FIRST BATTALION THE PARACHUTE REGIMENT (SPECIAL FORCES) 2. IC-73334X MAJOR ANIL URS ARMY 4TH BATTALION THE MARATHA LIGHT INFANTRY 3. 3003914X HAVILDAR ALOK KUMAR DUBEY ARMY THE RAJPUT REGIMENT, 44TH BATTALION THE RASHTRIYA RIFLES 4. WING COMMANDER VISHAK NAIR (28993) FLYING (PILOT) AIR FORCE 5. SHRI AMIT KUMAR, DEPUTY INSPECTOR GENERAL OF POLICE, JAMMU AND KASHMIR POLICE MHA 6. LATE SHRI MAHAVEER PRASAD GODARA, SUB-INSPECTOR (EXECUTIVE), CISF (POSTHUMOUSLY) MHA 7. LATE SHRI ERANNA NAYAKA, HEAD CONSTABLE, CISF (POSTHUMOUSLY) MHA 8. LATE SHRI MAHENDRA KUMAR PASWAN, CONSTABLE/DCPO, CISF (POSTHUMOUSLY) MHA 9. LATE SHRI SATISH PRASAD KUSHWAHA, CONSTABLE (FIRE) ONGC, MUMBAI, MHA CISF (POSTHUMOUSLY) BAR TO SENA MEDAL(GALLANTRY) 1. IC-65911K LIEUTENANT COLONEL AMIT KANWAR, SENA MEDAL ARMY THE PUNJAB REGIMENT, 22ND BATTALION THE RASHTRIYA RIFLES 2. IC-66127H LIEUTENANT COLONEL AMRENDRA PRASAD DWIVEDI, SENA MEDAL ARMY THE ASSAM REGIMENT, 42ND BATTALION THE RASHTRIYA RIFLES 3. IC-72542A MAJOR AMIT SAH, SENA MEDAL ARMY THE GARHWAL RIFLES, 14TH BATTALION THE RASHTRIYA RIFLES 4. IC-75350N MAJOR AKHIL KUMAR TRIPATHI, SENA MEDAL THE RAJPUT REGIMENT, 10TH BATTALION ARMY THE RASHTRIYA RIFLES 5. JC-4141561Y NAIB SUBEDAR ANIL KUMAR, SENA MEDAL ARMY 9TH BATTALION THE PARACHUTE REGIMENT (SPECIAL FORCES) SENA MEDAL(GALLANTRY) 6. IC-63375N LIEUTENANT COLONEL MANOJ KUMAR BHARDWAJ ARMY THE REGIMENT OF ARTILLERY, 36TH BATTALION THE RASHTRIYA RIFLES 7. IC-67124F LIEUTENANT COLONEL RAKESH KUMAR ARMY 19TH BATTALION THE GARHWAL RIFLES 8. -

1251 Governor Addresses Special Sainik Sammelan

No IPR (PR) 03/2008 Dated, Naharlagun, 15th November, 2010. PRESS RELERSE NO- 1251 Governor addresses special Sainik Sammelan Itanagar, Nov 14: Arunachal Pradesh Governor Gen JJ Singh addressed a special Sainik Sammelan of 17 Maratha Light Infantry, on its raising day celebration at Tenga in West Kameng district on Nov 14 last. The battalion was re-raised at Belgaum on 15th November 1962 under the Command of Lt. Col (Maj Gen) E D’Souza, PVSM (Retd.), reports PRO to Governor Speaking on the occasion, Gen Singh, who is the Honorary Colonel of the Regiment for life said, I feel proud to see your enthusiasm, battle readiness, disciple and high standard of your unit. I am very proud to learn about your warfare proficiency. Touching bit of the History of battalion, he said, in World War II in Myebon Peninsula your battalion was awarded with Battle Honour Ruywa. After you’re re-raising in 1962, you have continued the rich tradition in 1965 and 1971 wars. In operation Pawan and Operation Parakram, you displayed yourself as the premier, fervour and capable unit. Exhorting the officers and jawans, Gen Singh, whose grandfather fought in World War II along with 1 Maratha Light Infantry (103rd Battalion), 2 Maratha Light Infantry and 5 Maratha Light Infantry said, in my life I am an example for you that a soldier’s son can be a Colonel and a Colonel’s son can be a General. I always kept my motto and that is ‘Fight to Win’ and ‘Win by a knock out punch.’ There is no second best in war. -

Jangi Paltan: Moments of Glory (1St Battalion Maratha Light Infantry)

scholar warrior Jangi Paltan: Moments of Glory (1st Battalion Maratha Light Infantry) SATISH NAMBIAR Preamble In early January 1971, I was posted from the Military Operations Directorate of the Army Headquarters to the 1st Battalion, Maratha Light Infantry (Jangi Paltan). The Paltan was then in Nagaland and was part of 95 Mountain Brigade under 8 Mountain Division. In early September, my name came up for attending the Senior Command course at the then College of Combat (now Army War College). As war clouds gathered over the subcontinent, the course was terminated prematurely, and we were directed to return to our units post-haste. I rejoined the battalion on November 5, 1971, at a location south of Tura in Meghalaya on the border with Bangladesh, to which location it had moved as part of 95 Mountain Brigade operationally under 101 Communication Zone Area. I was asked to assume command of ‘Y’ Company (also referred to in the battalion as ‘VC’ Company in context of the fact that Sepoy Namdeo Jadhav of the company had been awarded the Victoria Cross at the battle of the Senio river in Italy during World War II). A Copy-Book Ambush The battalion was actively engaged in patrolling, raids and ambushes across the border in preparation for the war that was to inevitably follow. Though the citation for the award of the Vir Chakra is specific to my actions during the intense battle at Jamalpur on December 10-11, 1971, it would be of interest to the readers 120 ä SPRING 2020 ä scholar warrior scholar warrior to be made aware of the details of an ambush undertaken by the battalion on the night of November 13/14, 1971. -

Armed Forces Tribunal, Regional Bench, Kochi, Sitting Circuit Bench At

ARMED FORCES TRIBUNAL, REGIONAL BENCH, KOCHI, SITTING CIRCUIT BENCH AT PARA REGIMENTAL TRAINING CENTRE, BANGALORE O A NOS.127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135,136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153 and 154 of 2013 TUESDAY, THE 4th DAY OF MARCH 2014/13th PHALGUNA, 1935 CORAM: HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE SHRIKANT TRIPATHI, MEMBER (J) HON'BLE VICE ADMIRAL M.P.MURALIDHARAN,AVSM & BAR, NM, MEMBER (A) O.A.No.127 of 2103 APPLICANT: NO.2809673K EX-RECRUIT/CHEF TILBIR DARGEE, AGED 24 YEARS, MARATHA LIGHT INFANTRY, S/O.SHRI DARGEE, AT: CHEHEMI, PO-ASEEWA CHAURA, THE-TULOLUM PE3AK & CHEHEMI, DISTT-GULUNI, WEST NEPAL. BY ADV. SRI. RAMESH C.R. versus RESPONDENTS: 1. UNION OF INDIA, THROUGH THE SECRETARY, MINISTRY OF DEFENCE(ARMY), SOUTH BLOCK, NEW DELHI – 110001. 2. THE CHIEF OF ARMY STAFF, DHQ P.O., INTEGRATED HQRS, MINISTRY OF DEFENCE, SOUTH BLOCK. NEW DELHI – 110001. 3. THE COMMANDANT, THE MARATHA LIGHT INFANTRY, REGIMENTAL CENTRE, BELGAUM, KARNATAKA STATE 590 009. 4. THE OFFICER-IN-CHARGE (RECORDS) RECORDS, THE MARATHA LIGHT INFANTRY, BELGAUM, KARNATAKA STATE -590 009. BY ADV. SRI. K.M.JAMALUDHEEN, SENIOR PANEL COUNSEL. 2 OA.127/2013 & connected cases O.A.NO.128 OF 2013:- APPLICANT:- NO.2809675P EX-RECRUIT MAN BAHADUR B.K, AGED 24 YEARS, MARATHA LIGHT INFANTRY, S/O SHRI BAHADUR, VILL: TALLO LAMAI BRATHAW, P O- GALKOT HATIYA, TEHSIL-DAHULAGARI, DISTT-BAGLUNG, NEPAL. BY ADV.SRI.C.R.RAMESH versus RESPONDENTS:- 1. THE UNION OF INDIA, THROUGH THE SECRETARY, MINISTRY OF DEFENCE (ARMY), SOUTH BLOCK, NEW DELHI-110001.