Civilian Structures As Military Restrictions the Sudden Transition to Heavy Tanks in Sweden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Soviet-German Tank Academy at Kama

The Secret School of War: The Soviet-German Tank Academy at Kama THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ian Johnson Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Master's Examination Committee: Jennifer Siegel, Advisor Peter Mansoor David Hoffmann Copyright by Ian Ona Johnson 2012 Abstract This paper explores the period of military cooperation between the Weimar Period German Army (the Reichswehr), and the Soviet Union. Between 1922 and 1933, four facilities were built in Russia by the two governments, where a variety of training and technological exercises were conducted. These facilities were particularly focused on advances in chemical and biological weapons, airplanes and tanks. The most influential of the four facilities was the tank testing and training grounds (Panzertruppenschule in the German) built along the Kama River, near Kazan in North- Central Russia. Led by German instructors, the school’s curriculum was based around lectures, war games, and technological testing. Soviet and German students studied and worked side by side; German officers in fact often wore the Soviet uniform while at the school, to show solidarity with their fellow officers. Among the German alumni of the school were many of the most famous practitioners of mobile warfare during the Second World War, such as Guderian, Manstein, Kleist and Model. This system of education proved highly innovative. During seven years of operation, the school produced a number of extremely important technological and tactical innovations. Among the new technologies were a new tank chassis system, superior guns, and - perhaps most importantly- a radio that could function within a tank. -

Updates (1.3): New Scenario Loading Screen "Panzer III Ausf

INTRODUCTION Codename: PANZERS Phase 3 is a modification/total conversion package for the RTS game Codename: PANZERS Phase 2™. The mod is completely free, so trying to sell this mod is strictly prohibited. This is not an actual game but a modification package (or mod). WHAT’S NEW IN VERSION 1.3 Updates (1.3): New scenario loading screen "Panzer III Ausf. J" (created by VPf2/M&M) New desert scenario “DAK Mission” (created by Lucas_de_Escola) New scenario "End of the Line [1942]" (highly detailed map, new units, realistic gameplay)(created by VPf2) American shotgun squad (created by VPf2, custom skins, sounds and models) British A-34 Comet heavy tank (fully operatable 3xMG with custom SFX, edited & converted by VPf2) Custom skin for A-34 Comet (by VPf2) Winter skin for A-34 Comet (by VPf2) Panzer II Ausf. F tank Standard, African, 2xCamo and Winter skins (custom SFX, edited & converted by VPf2) Soviet NKL-16 snowmobile (converted by VPf2) German Wurfgerät 41 multiple rocket launching platform standard and winter skins (by VPf2) Winter skin for PaK 43 (by VPf2) New winter and African skin for the British Cromwell (VPf2) German Panzer III Ausf. J medium tank (3xMG, converted by VPf2) Camo skin for Panzer III Ausf. J (VPf2) Soviet KV-1C (custom SFX, converted, edited, re-skined, by VPf2) Winter skin for Soviet KV-1C (by VPf2) Winter Skin American M10 Wolverine (Skin by VPf2) Winter skins for German and Soviet reflectors/searchlights (skins by VPf2) Winter skin for the Sd. Kfz. 302 Goliath (VPf2) African skin for Crusader (by Kristof, edited by VPf2) African skin for Matilda MK II (by Kristof, edited by VPf2) Standard skin for Crusader (VPf2) Standard skin for Daimler MK I "Dingo" (old skin now as African)(VPf2) Camo 3 skin for Panzer III Ausf. -

Farbe 1-" 1934-45 Nzer "Maus" "Panther"· V Panzer "Königstiger"· IV· M Und Panzer "Tiger" 111· VI Panzer Panzer 11· Panzer I· Panzer

Sandini Archiv m nzer "Neubaufahrzeug" . Panzer I· Panzer 11· Panzer 111· Panzer IV· Panzer V "Panther"· 1-" Farbe Panzer VI "Tiger" und "Königstiger"· "Maus" 1934-45 Sonderheft 'CI ft D WAFFEN RSENAL 14.80 • 0. •Sandini Archiv Ein Kampfpanzer IV der Ausführung H. Sandini Archiv "Neubaufahrzeug" . Panzer I . Panzer II . Panzer III . Pan zer IV . Panzer V "Panther" . Deutsche Panzer VI "Tiger" und "Königs• tiger" . "Maus" Kampfpanzer inFarbe 1934-1945 Sonderheft der Waffen-Arsenal-Reihe Horst Scheibert Podzun-Pallas-Verlag GmbH - 6360 Friedberg 3 (Dorheim) Sandini Archiv Quellen: (zumeist le tzten ) AusrLi hrunge n und zeige n nur die für eine Bewer - Reihe: DAS WAFFENARSENAL IUng wi chtigste n Date n . Bei de n PS-Zahlen sind di e der Dauer - Archiv Podzun-Pallas- Verlag leistungen ge nomm en word en , da die der Höchstleistungen nur - H. L. Doyle (Skizze n) - Farbbilder Einb and: Horst Helmus th eoretbchcr Art sind. Von besonderem Interesse ist der Daten - EDITA S. A. Lausanne ve rgl eich auf Seite 52. Copyright 1985 PODZUN-PALLAS-VERLAG GMBH, 6360 Friedberg 3, Markt 9 Alle Rechte, auch die des auszugsweisen Nachdrucks, beim Podzun-Pallas- Verlag GmbH, Markt 9, 6360 Friedberg 3 Der Kampfpanzer Technische Herstellung: Freiburger Graphische Betriebe, 7800 Freiburg ISBN 3-7909-0239-X Neubaufahrzeug Das Waffen-Arsenal: Gesamtredaktion Horst Scheibert Unter der Tarnbezeichnung " Großtraktor" wurden in den Jahren Vertrieb: Alleinvertrieb 1927 bis 1929 Erfahrungen zum Bau schwerer Panzer gesammelt. Podzun-Pallas-Verlag GmbH für Österreich : Jedoch erst 1933 konnte das Oberkommando des Heeres einen Markt 9, Postfach 314 Pressegroßvertrieb Salzburg Auftrag zur Entwicklung dieser Panzer, zu denen ja nicht nur ein 6360 Friedberg 3 (Dorheim) 5081 Salzburg·Anif F ahrgesteU und Motor, sondern auch Panzerung und Waffen Telefon (0603 1)3 131 und 3160 Niederalm 300 gehörten, unter der Bezeichnung "Neubaufahrzeug", geben. -

MECHANIZED GHQ UNITS and WAFFEN-SS FORMATIONS (28Th June 1942) the GERMAN WORLD WAR II ORGANIZATIONAL SERIES

GERMAN WORLD WAR II ORGANIZATIONAL SERIES Volume 4/II MECHANIZED GHQ UNITS AND WAFFEN-SS FORMATIONS (28th June 1942) THE GERMAN WORLD WAR II ORGANIZATIONAL SERIES 1/I 01.09.39 Mechanized Army Formations and Waffen-SS Formations (3rd Revised Edition) 1/II-1 01.09.39 1st and 2nd Welle Army Infantry Divisions 1/II-2 01.09.39 3rd and 4th Welle Army Infantry Divisions 1/III 01.09.39 Higher Headquarters — Mechanized GHQ Units — Static Units (2nd Revised Edition) 2/I 10.05.40 Mechanized Army Formations and Waffen-SS Formations (2nd Revised Edition) 2/II 10.05.40 Higher Headquarters and Mechanized GHQ Units (2nd Revised Edition) 3/I 22.06.41 Mechanized Army Divisions - (2nd Revised Edition) 3/II 22.06.41 Higher Headquarters and Mechanized GHQ Units (2nd Revised Edition) 4/I 28.06.42 Mechanized Army Divisions - (2nd Revised Edition) 4/II 28.06.42 Mechanized GHQ Units and Waffen-SS Formations 5/I 04.07.43 Mechanized Army Formations 5/II 04.07.43 Higher Headquarters and Mechanized GHQ Units 5/III 04.07.43 Waffen-SS Higher Headquarters and Mechanized Formations IN PREPARATION FOR PUBLICATION 2007/2008 7/I 06.06.44 Mechanized Army Formations 2/III 10.05.40 Army Infantry Divisions 3/III 22.06.41 Army Infantry Divisions IN PREPARATION FOR PUBLICATION 01.09.39 Landwehr Division — Mountain Divisions — Cavalry Brigade 10.05.40 Non-Mechanized GHQ Units Static Units 22.06.41 Mechanized Waffen-SS Formations Static Units 28.06.42 Higher Headquarters Army Divisions Static Units 04.07.43 Army Divisions Static Units 01.11.43 Mechanized Army Formations Mechanized GHQ Units Mechanized Waffen-SS Formations Army Divisions Static Units Higher Headquarters 06.06.44 Mechanized GHQ Units Mechanized Waffen-SS Formations Army Divisions Static Units Higher Headquarters 16.12.44 Mechanized Army Formations Mechanized GHQ Units Mechanized Waffen-SS Formations Army Divisions Static Units Higher Headquarters 1939 – 45 Luftwaffen Ground Combat Forces 1944 – 45 The 1944 Brigades 1939 – 45 Organizational Handbook GERMAN WORLD WAR II ORGANIZATIONAL SERIES by Leo W.G. -

January Cover.Indd

Accessories 1:350 Scale 1:72 Scale Various Scale Kits Big Ed Set Detail Sets NEW LANCASTER B Mk.III SALE Spitfire PR.XIX Color 1:72 Scale Big Ed Accessory Set For Airfix kit Detail Set EUB7282 $79.95 $71.96 EU73479 $19.95 $14.99 SALE Vampire T.11 Color Interior Big Sin Set EU73480 $24.95 $18.99 NEW B-17G Engines Big Sin Set SALE Ilyushin Il-2M3 Self Adhesive Color Tamiya EU73481 $22.95 $16.99 For HK Model kit EUSIN63202 $110.00 $99.00 SALE Typhoon Mk.Ib Self Adhesive Color Airfix EU73483 $24.95 $18.99 Brassin SALE Lancaster B Mk.III Dambuster Interior Self Adhesive Color Detail Set For Airfix kit. RAF WWII Pt4 Figures Russian WWI 3D Self Adhesive Color NEW Il-2 Exhaust Stacks Brassin For Tamiya kit EU73484 $32.95 $24.99 EU672027 $7.95 FA0122 $25.99 $23.39 Detail Set For any kit. Gladiator Color Detail Set For Airfix kit. EU17524 $14.95 SALE S-21 Soviet Unguided Rocket Brassin EU73491 $14.95 EU672009 $9.99 Weapons Set III 1:76 Scale Lancaster B Mk.II Interior Self Adhesive Color HE35003 $9.99’ SALE Ju 88 Wheels Early Brassin For Revell kit. Detail Set For Airfix kit. EU672018 $6.99 EU73492 $26.95 $24.26 Il-2 Wheels Brassin For Tamiya kit. Fw 190A-8 Self Adhesive Color Airfix kit German Pilots and Ground Crew EU672026 $7.95 EU73493 $19.95 $17.96 RG2400 SALE PSP Display From Germany $20.99 $18.89 Detail Sets EU7701 $2.99 NEW SH-3D Sea King Exterior Cyber Hobby kit F-22 Interior Color Zoom Self Adhesive Detail Me 410 Canopy (1) EU72562 $29.95 $26.96 EUSS379 $14.95 SQ9153 NEW Lancaster B Mk.I/B Mk.III Bomb Bay Hellcat Mk.I Color Zoom Self Adhesive Detail $4.95 EUSS414 $9.95 Detail Set For Airfix kit DH Mosquito VI Canopy (2) for Airfix kit EU72577 $32.95 $29.66 Bf 109E Interior Color Zoom Self Adhesive SQ9156 $4.95 EUSS453 $10.95 RAF Airfield Recovery Set NEW Bf 110G-4 Weekend Edition Color Detail SALE Spitfire Mk.XVI/XIV AX03305 $10.99 Sunderland Mk.I Interior Color Zoom Self SQ9157 $4.95 $3.99 Set For Eduard kit Adhesive Detail Set For Italeri kit. -

A Modeller's Guide on How to Identify

A modeller’s guide on how to identify - German WWII Tank, Pak, Flak, Artillery Weapons and Ammunition. Directions for use of the outlines: There are three outlines. First outline contains information on the vehicle itself, starting with the Sd Kfz. number, name/designation and what armament it carried. Sd.Kfz. No. Name Armament Two 7,9 mm. MG 34 Sd.Kfz. 181 Pz.Kpfw. VI Ausf. E (Tiger ) One 8,8 cm. Kw.K. 36 L/56 Sd.Kfz. 181 = Sonderkraftfahrzeug 181 (Special motor vehicle 181). Pz.Kpfw. VI Ausf. E (Tiger ) = Panzerkampfwagen 6 Ausführung E Tiger, (Armoured battle car 6 execution E Tiger) 7,9mm. MG34 = Maschinengewehr 34, (Machinegun 34). 8,8cm. Kw.K. 36 L/56 = 8,8 Zentimeter Kampfwagenkanone 36 Lange/561, (8,8 centimetre battle car gun 36 length 56). 1. Lange/56 = Length of gun without muzzle brake expressed as a multiple of the calibre - 8,8 cm. Kw.K. 36 L/56 = 88mm x 56 = 4.92m. Second outline contains information on the gun type, in which way the ammunition was feed to the gun and how the ammunition was kept or transported by way of example: German designation of the gun Gun feed by Ammunition storage 8,8 cm. Kw.K. 36 L/56 Single shot Wooden box 3 cartridges. 8,8cm. Kw.K. 36 L/56 = 8,8 Zentimeter Kampfwagenkanone 36 Lange/56. Single shot = The gun was feed by a single shot. Wooden box 3 cartridges = Description on how the ammunition was kept and packed. Third outline describes the same guns as in the two previous outlines but contains more detailed information on what kind of cartridges the gun used, colours of the cartridge case and shell, what a standard cartridge looked like, shell type and what kind of ammunition identification markings there were printed on the specific box the ammunition was transported in. -

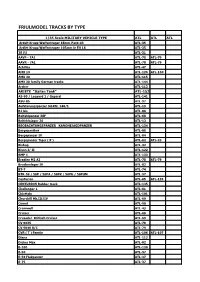

Friulmodel Tracks by Type

FRIULMODEL TRACKS BY TYPE 1/35 Scale MILITARY VEHICLE TYPE ATL ATL ATL Ardelt Krupp Waffentrager 88mm Pack-43 ATL-35 Ardlet Krupp Waffentrager 105mm le FH 18 ATL-35 35 (t) ATL-31 AAVP - 7A1 ATL-78 ATL-79 AAVR - 7A1 ATL-78 ATL-79 Achilles ATL-47 AMX 13 ATL-126 ATL-130 AMX 30 ATL-115 AMX 30 family German tracks ATL-144 Archer ATL-113 ARIETE "Italian Tank" ATL-152 AS-90 / Leopard 1 / Gepard ATL-141 ASU-85 ATL-97 Aufklarungspanzer Sd.Kfz. 140/1 ATL-13 B1 bis ATL-88 Belfehlpanzer 38F ATL-68 Belfehlsjager 38 ATL-13 BEOBACHTUNGSPANZER KANONEJAGDPANZER ATL-134 Bergepanther ATL-08 Bergepanzer IV ATL-04 Bergepanzer Tiger ( P ) ATL-62 ATL-23 Bishop ATL-32 Bison I/ II ATL-122 BMP 1 ATL-133 Bradley M2 A2 ATL-78 ATL-79 Bruckenleger IV ATL-02 BT-7 ATL-74 BTR-50 / 50P / 50PA / 50PK / 50PU / 50PUM ATL-97 Centurion ATL-65 ATL-135 CENTURION Rubber track ATL-135 Challenger 1 ATL-81 Chieftain ATL-101 Churchill Mk.III/IV ATL-60 Comet ATL-90 Cromwell ATL-43 Cruiser ATL-69 Crusader Britisch Cruiser ATL-69 CV 9035 ATL-79 CV 9040 B/C ATL-79 CVR ( T ) Family ATL-106 ATL-107 Diana ATL-112 Dicker Max ATL-02 E-100 ATL-120 E-50 ATL-37 E-50 Flakpanzer ATL-37 E-75 ATL-37 E-75 Flakpanzer ATL-37 Elefant ATL-23 Ersatz M10 ATL-08 Famo Half-Track ATL-57 ATL-58 Feldhaubitze 18/1 Sd.Kfz. -

German World War Ii Organizational Series

GERMAN WORLD WAR II ORGANIZATIONAL SERIES Volume 2/II HIGHER HEADQUARTERS — MECHANIZED GHQ UNITS (1.05.1940) THE GERMAN WORLD WAR II ORGANIZATIONAL SERIES 1/I 01.09.39 Mechanized Army Formations and Waffen-SS Formations (3rd Revised Edition) 1/II-1 01.09.39 1st and 2nd Welle Army Infantry Divisions 1/II-2 01.09.39 3rd and 4th Welle Army Infantry Divisions 1/III 01.09.39 Higher Headquarters — Mechanized GHQ Units — Static Units (2nd Revised Edition) 2/I 10.05.40 Mechanized Army Formations and Waffen-SS Formations (2nd Revised Edition) 2/II 10.05.40 Higher Headquarters and Mechanized GHQ Units (2nd Revised Edition) 3/I 22.06.41 Mechanized Army Divisions - (2nd Revised Edition) 3/II 22.06.41 Higher Headquarters and Mechanized GHQ Units (2nd Revised Edition) 4/I 28.06.42 Mechanized Army Divisions - (2nd Revised Edition) 4/II 28.06.42 Mechanized GHQ Units and Waffen-SS Formations 5/I 04.07.43 Mechanized Army Formations 5/II 04.07.43 Higher Headquarters and Mechanized GHQ Units 5/III 04.07.43 Waffen-SS Higher Headquarters and Mechanized Formations IN PREPARATION FOR PUBLICATION 2007/2008 7/I 06.06.44 Mechanized Army Formations 2/III 10.05.40 Army Infantry Divisions 3/III 22.06.41 Army Infantry Divisions IN PREPARATION FOR PUBLICATION 01.09.39 Landwehr Division — Mountain Divisions — Cavalry Brigade 10.05.40 Non-Mechanized GHQ Units Static Units 22.06.41 Mechanized Waffen-SS Formations Static Units 28.06.42 Higher Headquarters Army Divisions Static Units 04.07.43 Army Divisions Static Units 01.11.43 Mechanized Army Formations Mechanized GHQ Units Mechanized Waffen-SS Formations Army Divisions Static Units Higher Headquarters 06.06.44 Mechanized GHQ Units Mechanized Waffen-SS Formations Army Divisions Static Units Higher Headquarters 16.12.44 Mechanized Army Formations Mechanized GHQ Units Mechanized Waffen-SS Formations Army Divisions Static Units Higher Headquarters 1939 – 45 Luftwaffen Ground Combat Forces 1944 – 45 The 1944 Brigades 1939 – 45 Organizational Handbook GERMAN WORLD WAR II ORGANIZATIONAL SERIES by Leo W.G. -

Firestorm: Norway

BY GÍSLI JÖKULL GÍSLASON WITH DANE TKACS, EIRIK ULSUND AND MAURICE V. HOLMES JR. I Contents Operation Weserübung 4 Campaign Outcome 24 Firestorm: Norway 6 Warriors 25 Using the Maps 7 Turns 29 The Strategic Game 10 Firestorm Troops 34 The Game Turn 13 Firestorm Terms 38 How Firestorm Works 18 The General’s Wargame 39 General - Planning Phase 18 Setting up the Campaign 40 Commander - Battle Phase 19 Firestorm: Norway Maps 42 Strategic Phase 23 Introduction Why Norway? At first glance it may sound obscure, but it studied the Campaign so it was a lot of work. Actually isn’t. It was the first battlefield where British, French and Firestorm Norway could be called Firestorm Weserübung German soldiers would battle on land in World War II. since it does cover Denmark in an abstract way. I went for It would last longer than the Battle of France. It was the Firestorm Norway for reasons of familiarity with most people. first modern combined arms operation with navy, air and In all my Firestorms I have tried to capture the essence of land forces. One which the Wehrmacht performed to their each Campaign and soon I realised that it was impossible German perfection. It was a gross violation of neutral to separate the Naval Actions from the land Campaign and states and Operation Weserübung would conclude in the this added a whole new dimension. Another thing about the occupation of Norway and Denmark for the reminder of Battle of Norway is that Norway is very long and making the war in Europe. -

Gepanzerte Kleinfahrzeuge Leichte Panzerkampfwagen Mittlere

Einleitung 5 PzKpfw. III Ausf. N, Glossar 7 Sd.Kfz. 141/2 Sturmpanzer III 42 PzKpfw. IV Ausf. B, Sd.Kfz. 161 44 Gepanzerte Kleinfahrzeuge PzKpfw. IV Ausf. C bis F, Sd.Kfz. 161.... 45 Gepanzerter Munitionsschlepper PzKpfw. IV Ausf. G, Sd.Kfz. 161/1 VK 302 8 F2 und F6 48 Schwerer Ladungsträger, Sd. Kfz. 301 .... 9 PzKpfw. IV Ausf. H, Sd.Kfz. 161/2 und J . 50 Leichter Ladungsträger, Gefechtsaufklärer VK 1602 53 Sd. Kfz. 302, Goliath 10 VK 3002 (DB) 54 Mittlerer Ladungsträger Springer PzKpfw. V Ausf. D, Sd. KFZ. 304 11 Sd.Kfz. 171, Panther 55 PzKpfw. V Ausf. A, Leichte Panzerkampfwagen Sd.Kfz. 171, Panther 58 PzKpfw. lAusf. A, Sd.Kfz. 101 12 PzKpfw. V Ausf. G, PzKpfw. I Ausf. B, Sd.Kfz. 101 14 Sd.Kfz. 171, Panther 60 Kleiner Panzerbefehlswagen PzKpfw. V, Sd.Kfz. 171, Panther II 62 Sd.Kfz. 265 15 PzKpfw. I Ausf. C (VK 601) Schwere Kampfpanzer Sd.Kfz. 101 16 PzKpfw. Neubaufahrzeug V und VI 64 PzKpfw. I Ausf. F (VK 1801) VK 4501 (P) 65 Sd.Kfz. 101 17 PzKpfw. VI Ausf. E, Sd.Kfz. 181, Tiger ... 66 PzKpfw. II Ausf. b, Sd.Kfz. 121 18 PzKpfw. VI Ausf. B, PzKpfw. II Ausf. C, Sd.Kfz. 121 20 Sd.Kfz. 182, Tiger II 70 PzKpfw. II Ausf. D und E, Sd.Kfz. 121 ... 22 PzKpfw. VIII, Maus 72 PzKpfw. II (Flamm), E-100 73 Sd.Kfz. 122, Flamingo 23 PzKpfw. II Ausf. F, Sd.Kfz. 121 24 Panzerjäger / Jagdpanzer PzKpfw. II Ausf. L, 4,7-cm-Pak (t) (St) Sd.Kfz. -

ALL TIME INDEX Volumes 1-16

1935 – Basic airbrushes ALL TIME INDEX Volumes 1-16 ©2002, Kalmbach Publishing Co., 21027 Crossroads Circle, P. O. Box 1612, Waukesha, WI 53187-1612 Included in this index are articles and departments in the 1982-1998 issues of FineScale Modeler. Addtional copies of this index may be obtained by sending a large self-addressed, stamped envelope to our Customer Sales and Service Deparment at the address above. *1935 Morgan, Dec 1998 p28 Curtiss P-36, March 1994 p52 Attack Lizard, Summer 1983 p52 Honda Civic, Hasegawa, March 1996 p78 Aungst, David, A-4M Skyhawk, Sept 1997 p64 A Snapping up Ertl/AMT’s ‘93 Camaro, Jan 1994 p42 Aurelio Gimeno Ruiz’s “Star of Africa” diorama, July 1997 T-33A, Hobbycraft, March 1995 p90 p28 A-10A Ghost scheme, U.S. Air Force, July 1994 p40 Tackling Tamiya’s Triceratops, July 1994 p58 *Aurora kits that never were, Oct 1998 p50 A-10A MASK-10A schemes, Feb 1989 p56 *Amazing aircraft cutaways, May 1999 p26 *Aurora’s Albatros, Dec 1999 p71 A-4M Skyhawk conversion, Sept 1997 p64 *"American Graffiti" Deuce coupe, Nov 1999 p66 Aurora’s Batmania from the 1960s, Jan 1990 p33 A-5A Vigilante, Jan 1993 p42 Anderson, Ray Aurora’s colorful WWII 1994 fighters, WWII 1994 p26 A-6 Intruder diorama, Nov 1992 p26 Art of the diorama, Choosing a subject for a scene that Aurora’s Creature of the Black Lagoon, Sept 1996 p66 A6M2 Zero, July 1992 p22 tells a story, April 1987 p22 Aurora’s Dick Tracy Space Coupe, March 1997 p58 *A-36: Mustang dive bomber, Dec 1999 p36 Art of the diorama, Designing boxed scenes, June 1987 p50 Aurora’s F-9F -

German Weapons

GERMANY v 7.9 Stand Class Move Def. Weapons Ammo ROF C M L E IDF Year Horse-drawn Vehicles Cart II-1/- 8/4W Soft MG Cart II-1/- 12/8W Soft Wagon III,-2/- 8/2W Soft Light limber II-1/II 12/8W Soft Limber III-1/III 8/6W Soft Pack animal II-1/- 6/4L Soft Soft-Skinned Vehicles Car II-H/- 40/12W Soft Kubelwagen II-H/I 44/16W Soft Schwimwagen II-H/1 44/16WA Soft RSO III-2/I 12/12T Soft 43 sWS IV-3/III 16/12W Soft 44 SdKfz 6 tractor III-2/IV 24/12W Soft SdKfz 7 tractor III-2/V 22/12W Soft SdKfz 10 tractor III-2/III 28/16W Soft Maultier IV-2/III 22/12W Soft 43 Light truck II-1/II 48/16W Soft Medium truck III-2/III 36/8W Soft Heavy truck IV-3/IV 24/6W Soft Armored Cars and Transporters sWS gepz. IV-2/III 18/8W 2/1W 44 SdKfz 4 tractor III,-2/III 18/10W 2/1W 44 SdKfz 221 AC III 48/12W 1/1W T:MG SA 1 6(7)W 12(5)W xx xx 38 SdKfz 222 AC III 48/12W 1/1W T:MG SA 1 6(7)W 12(5)W xx xx 37 T:20L55 HE 2 6(4)W 12(3)W 18(2)W 36(1)W AP 2 6(7)3 12(5)2 18(3)1 36(1)0 -HV 2 6(7)4 12(5)2 xx xx SdKfz 223 AC III 48/12W 1/1W T:MG SA 1 6(7)W 12(5)W xx xx 38 SdKfz 231 AC III 48/8W 1/1W T:20L55 HE 2 6(4)W 12(3)W 18(2)W 36(1)W 33 (6 rad) AP 2 6(7)3 12(5)2 18(3)1 36(1)0 -HV 2 6(7)4 12(5)2 xx xx T:MG SA 1 6(7)W 12(5)W xx xx SdKfz 231 AC III 48/16W 2/1W T:20L55 HE 2 6(4)W 12(3)W 18(2)W 36(1)W 38 (8 rad) AP 2 6(7)3 12(5)2 18(3)1 36(1)0 -HV 2 6(7)4 12(5)2 xx xx T:MG SA 1 6(7)W 12(5)W xx xx SdKfz 232 AC III 48/16W 2/1W T:20L55 HE 2 6(4)W 12(3)W 18(2)W 36(1)W 38 AP 2 6(7)3 12(5)2 18(3)1 36(1)0 -HV 2 6(7)4 12(5)2 xx xx T:MG SA 1 6(7)W 12(5)W xx xx SdKfz 233 AC III 48/16W 2/1W T:75L24