Color and Number Patters in the Symbolic Cosmologies of the Crow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CSE Big Brochure

PRODUCT CATALOG ULTIMATE OPTIQUE GLASS Cardinal is pleased to offer this industry-exclusive product combining cast and clear glass in the same panel. See page 14 for more details. www.cardinalshower.com LOUISVILLE MANUFACTURING FACILITY CARDINAL SHOWER ENCLOSURES Cardinal Shower Enclosures is a full service domestic manufacturer of shower enclosures, offering a wide selection of models, finishes and glass options, from cast to patterned glass. Our enclosures are engineered to the highest possible standards for maximum reliability and carry a lifetime guarantee against defects in craftsmanship and materials on extruded aluminum parts. With our network of trucks and locations across the U.S. we can reach 80% of the population with twice-a-week deliveries. From our in-house 80,000 square foot tempering facility, we can be your single source for enclosures and Venetian Cast Glass. While the industry standard is a 20% reject rate for tempered panels, we’re running at a less than 2% reject rate, virtually eliminating the need for return trips to the job. Our large 280,000 square foot manufacturing facility means we can provide hundreds of enclosures at a time for your large projects. We also produce all of our stunning cast glass in-house, ensuring the best quality for your enclosures and architectural glass applications. 2 SLIDING DOOR ENCLOSURES OPTIONS SPECIFICATIONS Cardinal Builder Series 4 Cast Glass Patterns 15 Cardinal Shower Enclosures, manufactured by Hoskin & Craftsman Builder Series 4 Heavy Glass Patterns 16 Muir, Inc., are fabricated with extruded 5000 and 6000 Craftsman Series 5 Thin Glass Patterns 17 series billet. All exposed surfaces are polished before anodizing in the Cardinal line. -

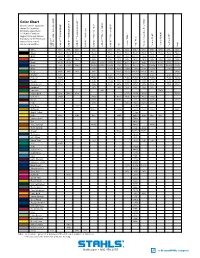

Color Chart ® ® ® ® Closest Pantone® Equivalent Shown

™ ™ II ® Color Chart ® ® ® ® Closest Pantone® equivalent shown. Due to printing limitations, colors shown 5807 Reflective ® ® ™ ® ® and Pantone numbers ® ™ suggested may vary from ac- ECONOPRINT GORILLA GRIP Fashion-REFLECT Reflective Thermo-FILM Thermo-FLOCK Thermo-GRIP ® ® ® ® ® ® ® tual colors. For the truest color ® representation, request Scotchlite our material swatches. ™ CAD-CUT 3M CAD-CUT CAD-CUT CAD-CUT CAD-CUT CAD-CUT CAD-CUT Felt Perma-TWILL Poly-TWILL Thermo-FILM Thermo-FLOCK Thermo-GRIP Vinyl Pressure Sensitive Poly-TWILL Sensitive Pressure CAD-CUT White White White White White White White White White* White White White White White Black Black Black Black Black Black Black Black Black* Black Black Black Black Black Gold 1235C 136C 137C 137C 123U 715C 1375C* 715C 137C 137C 116U Red 200C 200C 703C 186C 186C 201C 201C 201C* 201C 186C 186C 186C 200C Royal 295M 294M 7686C 2747C 7686C 280C 294C 294C* 294C 7686C 2758C 7686C 654C Navy 296C 2965C 7546C 5395M 5255C 5395M 276C 532C 532C* 532C 5395M 5255C 5395M 5395C Cool Gray Warm Gray Gray 7U 7539C 7539C 415U 7538C 7538C* 7538C 7539C 7539C 2C Kelly 3415C 341C 340C 349C 7733C 7733C 7733C* 7733C 349C 3415C Orange 179C 1595U 172C 172C 7597C 7597C 7597C* 7597C 172C 172C 173C Maroon 7645C 7645C 7645C Black 5C 7645C 7645C* 7645C 7645C 7645C 7449C Purple 2766C 7671C 7671C 669C 7680C 7680C* 7680C 7671C 7671C 2758U Dark Green 553C 553C 553C 447C 567C 567C* 567C 553C 553C 553C Cardinal 201C 188C 195C 195C* 195C 201C Emerald 348 7727C Vegas Gold 616C 7502U 872C 4515C 4515C 4515C 7553U Columbia 7682C 7682C 7459U 7462U 7462U* 7462U 7682C Brown Black 4C 4675C 412C 412C Black 4C 412U Pink 203C 5025C 5025C 5025C 203C Mid Blue 2747U 2945U Old Gold 1395C 7511C 7557C 7557C 1395C 126C Bright Yellow P 4-8C Maize 109C 130C 115U 7408C 7406C* 7406C 115U 137C Canyon Gold 7569C Tan 465U Texas Orange 7586C 7586C 7586C Tenn. -

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections C. Ross Hume Collection Hume, Carleton Ross (1878–1960). Papers, 1838–1948. 10.50 feet. Attorney. Personal and business correspondence (1893–1948) relating to Hume’s family, his attendance at the University of Oklahoma, his contact with the university as an alumnus, and his law practice as an attorney for the Caddo Indians. Also included are numerous legal documents (1838–1948) relating to Indian claims and the Indians of Oklahoma, the Shirley Trading Post, the Anadarko, Oklahoma, area and the University of Oklahoma. ___________ Biographical Note: Carleton Ross Hume, who along with Roy P. Stoops made up the first graduating class of the University of Oklahoma in 1898. He was born at Tontogany, Ohio, in 1878. He was the son of Charles Robinson Hume and Annette Ross Hume. The Humes moved to Anadarko, Oklahoma Territory, in December of 1890, when Dr. Hume was appointed as government physician to the Anadarko Indian Agency. C. Ross Hume later served as attorney for the Caddo Nation, and a judge in Anadarko. Box 1 Native American Tribal Materials Apaches (1925-26) 1. Legal inquiry concerning an Apache woman Various Individual claims- includes letter to Hume from Sen. E. Thomas Folder of Clippings Cherokees 2. Power of Attorney Notes on Sequoyah Treaties with Republic of Texas (1836 and 1837) Cherokee Indians' Claim Texas Land Research notes - secondary sources Cheyennes 3. Historical notes including origins, dates of wars, movements, etc. 47th Congress, 1st session -1882. Message from the President of the United States. Confirmation of Certain Land in Indian Territory to Cheyenne and Arapahoe Indians Comanches 4. -

CARDINAL FLOWER Lobelia Cardinalis

texas parks and wildlife CARDINAL FLOWER Lobelia cardinalis ©Jim Whitcomb Cardinal flower has vivid scarlet flowers that seem to be particularly attractive to hummingbirds. This plant blooms during late summer and early fall when hummingbirds are passing through on their southerly migration. Hummingbirds are attracted to plants with red tubular flowers. Range Plants CARDINAL FLOWER Lobelia cardinalis Appearance Life Cycle Height: 6 inches to 6 feet Plant type: Perennial Flower size: Individual flowers are 2 inches long on 8 inch spikes Bloom time: May-October Flower color: Intense red Method of reproduction: Layering. Bend a Cardinal flowers produce one to several stalks stem over and partially bury it. It will that are topped by spikes of deep velvet red produce new plants from the leaf nodes. flowers. They form basal rosettes in the winter. Planting time: Young plants should be transplanted during early spring or late fall. Planting Information Soil: Moist sand, loam, clay or limestone, poor Legend Has It ... drainage is okay Sunlight: Prefers partial shade The scarlet-red flower was named for Spacing: 1 foot apart the red robes worn by cardinals in the Lifespan: Short lived perennials whose size Catholic Church. Although native to varies according to environmental conditions. North America, it's been cultivated in Europe since the 1600s for its lovely flower. One legend claims that touching the root of this plant will bring love to Now You Know! the lives of elderly women! = Cardinal flowers grow tallest and flower best in wet, partially sunny areas. = Cardinal flowers time their blooms with the Habitat fall migration of hummingbirds, their chief pollinator. -

Kiowa and Cheyenne's Story

Kiowa and Cheyenne's Story Along the Santa Fe Trail My life changed forever along the Santa Fe Trail. It was hot August 2, 2003 as my family traveled homeward to Littleton, Colorado from a family vacation through Kansas. This side of Dodge City my husband, Jeff, nine-year-old Michael and seven-year-old Stacia and I debated whether or not to stop at a Point of Interest close to the highway. It was educational and free, so, why not, we stopped. The parking lot was completely empty except for an elderly man sitting on a bench and two skinny dogs close by him. As we headed up the trail leading to a sign explaining the local history, the dogs approached us. We glanced at the man for permission to pet the dogs. He just smiled in silence. We petted their thin sides, receiving kisses in return. The brown Boxer mix and the black Lab wearily followed us up the trail, laying down each time we stopped. After a brief rabbit chase, both dogs returned, following us back to the dry, dusty parking lot. I told the man to call his dogs since we were leaving. He said they weren‛t his. But, they had to be; no one else was around. I called him a liar and we began arguing! A Winnebago arrived and Jeff asked if the dogs belonged to them. No. The old man kept telling me to take the dogs. Finally Jeff whispered to me that the dogs didn‛t act like they knew the old man any better than they did us. -

Tribal and House District Boundaries

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tribal Boundaries and Oklahoma House Boundaries ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 22 ! 18 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 13 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 20 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 7 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Cimarron ! ! ! ! 14 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 11 ! ! Texas ! ! Harper ! ! 4 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! n ! ! Beaver ! ! ! ! Ottawa ! ! ! ! Kay 9 o ! Woods ! ! ! ! Grant t ! 61 ! ! ! ! ! Nowata ! ! ! ! ! 37 ! ! ! g ! ! ! ! 7 ! 2 ! ! ! ! Alfalfa ! n ! ! ! ! ! 10 ! ! 27 i ! ! ! ! ! Craig ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! h ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 26 s ! ! Osage 25 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! a ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 6 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tribes ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 16 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! W ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 21 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 58 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 38 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tribes by House District ! 11 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 Absentee Shawnee* ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Woodward ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 2 ! 36 ! Apache* ! ! ! 40 ! 17 ! ! ! 5 8 ! ! ! Rogers ! ! ! ! ! Garfield ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 40 ! ! ! ! ! 3 Noble ! ! ! Caddo* ! ! Major ! ! Delaware ! ! ! ! ! 4 ! ! ! ! ! Mayes ! ! Pawnee ! ! ! 19 ! ! 2 41 ! ! ! ! ! 9 ! 4 ! 74 ! ! ! Cherokee ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ellis ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 41 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 72 ! ! ! ! ! 35 4 8 6 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 5 3 42 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 77 -

Vascular Plants and a Brief History of the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands

United States Department of Agriculture Vascular Plants and a Brief Forest Service Rocky Mountain History of the Kiowa and Rita Research Station General Technical Report Blanca National Grasslands RMRS-GTR-233 December 2009 Donald L. Hazlett, Michael H. Schiebout, and Paulette L. Ford Hazlett, Donald L.; Schiebout, Michael H.; and Ford, Paulette L. 2009. Vascular plants and a brief history of the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS- GTR-233. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 44 p. Abstract Administered by the USDA Forest Service, the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands occupy 230,000 acres of public land extending from northeastern New Mexico into the panhandles of Oklahoma and Texas. A mosaic of topographic features including canyons, plateaus, rolling grasslands and outcrops supports a diverse flora. Eight hundred twenty six (826) species of vascular plant species representing 81 plant families are known to occur on or near these public lands. This report includes a history of the area; ethnobotanical information; an introductory overview of the area including its climate, geology, vegetation, habitats, fauna, and ecological history; and a plant survey and information about the rare, poisonous, and exotic species from the area. A vascular plant checklist of 816 vascular plant taxa in the appendix includes scientific and common names, habitat types, and general distribution data for each species. This list is based on extensive plant collections and available herbarium collections. Authors Donald L. Hazlett is an ethnobotanist, Director of New World Plants and People consulting, and a research associate at the Denver Botanic Gardens, Denver, CO. -

Indian Lands of Federally Recognized Tribes of the United States

132°W 131°W 130°W 129°W 128°W 127°W 126°W 125°W 124°W 123°W 122°W 121°W 120°W 119°W 118°W 117°W 116°W 115°W 114°W 113°W 112°W 111°W 110°W 109°W 108°W 107°W 106°W 105°W 104°W 103°W 102°W 101°W 100°W 99°W 98°W 97°W 96°W 95°W 94°W 93°W 92°W 91°W 90°W 89°W 88°W 87°W 86°W 85°W 84°W 83°W 82°W 81°W 80°W 79°W 78°W 77°W 76°W 75°W 74°W 73°W 72°W 71°W 70°W 69°W 68°W 67°W 66°W 65°W 64°W 63°W 48°N 46°N 47°N Neah Bay 4 35 14 45°N Everett 46°N Taholah CANADA Seattle Nespelem 40 Aberdeen 44°N Wellpinit Browning Spokane 45°N Harlem Belcourt WAS HIN Box Wagner E GTO Plummer Elder IN N MA 10 Pablo E SUPER Wapato IO Poplar K R Toppenish A 43°N New L Town Fort Totten Red Lake NT 44°N O Lapwai RM Portland VE Sault MO Sainte Marie NTANA Cass Lake Siletz Pendleton 42°N K NH NORTH DAKOTA Ashland YOR EW 43°N Warm N Springs LA KE No H r Fort U t Yates Boston hw Billings R TS e Crow ET 41°N s Agency O S t HU Worcester O R N AC RE eg Lame Deer OTA NTARIO SS GON io MINNES E O MA 42°N n Sisseton K A Providence 23 Aberdeen L N I 39 Rochester R A Springfield Minneapolis 51 G Saint Paul T SIN I C WISCON Eagle H 40°N IDA Butte Buffalo Boise HO C I 6 41°N R M o E cky M SOUTH DAKOTA ou K AN ntai ICHIG n R A M egion Lower Brule Fort Thompson L E n Grand Rapids I io New York g 39°N e Milwaukee R Fort Hall R west 24 E d Detroit Mi E 40°N Fort Washakie K WYOMING LA Rosebud Pine Ridge Cleveland IA Redding Wagner AN Toledo LV 32 NSY PEN Philadelphia 38°N Chicago NJ A 39°N IOW Winnebago Pittsburgh Fort Wayne Elko 25 Great Plains Region Baltimore Des Moines MD E NEBRASKA OHIO D -

Pac-Clad® Color Chart

pa c - c l a d ® c O l O R c H a RT Cardinal Red Colonial Red Burgundy Terra Cotta Sierra Tan Mansard Brown Stone White Granite Sandstone Almond Medium Bronze Dark Bronze Slate Gray Bone White Musket Gray Charcoal Midnight Bronze Matte Black Cityscape Interstate Blue Hemlock Green Arcadia Green Patina Green Hunter Green Military Blue Award Blue Teal Hartford Green Forest Green Evergreen Denotes PAC-CLAD Metallic Colors Denotes Energy Star® Colors Denotes PAC-CLAD Cool Colors Kynar 500® or Hylar 5000® pre-finished galvanized steel and aluminum for roofing, curtainwall and storefront applications. Berkshire Blue Slate Blue PAC-CLAD Metallic Colors Zinc Silver Copper Penny Aged Copper Champagne Weathered Zinc PETERSEN ALUMINUM CORPORATION HQ: 1005 Tonne Road 9060 Junction Drive 10551 PAC Road 350 73rd Ave., NE, Ste 1 102 Northpoint Pkwy Ext, Bldg 1, Ste 100 Elk Grove Village, IL 60007 Annapolis Junction, MD 20701 Tyler, TX 75707 Fridley, MN 55432 Acworth, GA 30102 P: 800-PAC-CLAD P: 800-344-1400 P: 800-441-8661 P: 877-571-2025 P: 800-272-4482 F: 800-722-7150 F: 301-953-7627 F: 903-581-8592 F: 866-901-2935 F: 770-420-2533 pa c - c l a d ® c O l O R aVa I l a BI l ITY PAC-CLAD 3 year STeeL ALuMiNuM eNeRGy STANDARD RefLectiviTy EmissiviTy SRi 24ga. 22ga. .032 .040 .050 .063 ® COLORS exposuRe STAR Almond 0.56 0.83 0.27 64 √ √ √ √ √ • Arcadia Green 0.33 0.84 0.32 33 √ √ • Bone White 0.71 0.85 0.71 86 √ √ √ √ √ √ • Cardinal Red 0.42 0.84 0.41 45 √ √ √ • Charcoal 0.28 0.84 0.28 27 √ √ √ • Cityscape 0.37 0.85 0.34 39 √ √ √ √ • Colonial Red 0.34 -

Wildflower in Focus: Cardinal Flower

throated hummingbirds. Their vivid color is the traditional color of the robes worn by Roman Wildflower in Focus Catholic Cardinals - and thus the name. Their hue is also similar to the color of the native male bird Text by Melanie Choukas-Bradley that shares the name cardinal. Growing in wet Artwork by Tina Thieme Brown meadows, springs, freshwater marshes, and along streams, rivers, and ponds throughout the state, the Cardinal Flower cardinal flower is one of several members of the Lobelia cardinalis L. Lobelia genus native to Maryland and the only one Bellflower or Bluebell Family (Campanulaceae) with red flowers. Other Lobelias growing here [Some taxonomists place this genus in a separate have flowers ranging from blue to whitish-blue, family — the Lobelia Family (Lobeliaceae)] lilac, and rarely white. The cardinal flower blooms during the verdant days of mid to late summer and stays in bloom as autumn stirs. Specific Characteristics of the Cardinal Flower Flowers: Scarlet, irregular, 2-lipped, with a 2-lobed upper lip, a 3-lobed lower one and a tubular base. Sexual parts protrude in a beak-like fashion (see illustration). Flowers 1-2" long and wide in upright racemes. Five sepals are thin (almost hair-like). Leaves: Alternate, simple, lanceolate to oblong or narrowly ovate, tapered to apex and base, pubescent or glabrous. Toothed, often irregularly so (sometimes dentate). Short-petioled to sessile, 2-7" long. Height and Growth Habit: 1-5'; usually unbranched. Range: New Brunswick to Minnesota, south to the Gulf of Mexico. Herbal Lore: American Indians used the roots and leaves of this plant for a number of conditions, including syphilis, typhoid, fevers, headaches and rheumatism. -

TREMCO Color Chart

TREMCO Color Chart Our colors are deep, rich and true. Made of Valspar’s Fluropon® High Performance Hylar 5000®/Kynar 500® finish, they offer the ultimate in resistance against fading and weathering. In addition to our many standard colors, custom colors are also available. EXPRESS COLORS* Stone White l Bone White l Almond l Sandstone l Cityscape l Slate Gray l Sierra Tan l Medium Bronze l Dark Bronze l Clear Anodized STANDARD COLORS Charcoal l Midnight (Extra Dark) Matte Black Burgundy (Brandywine) Terra Cotta l Bronze Cardinal Red Sky Blue Interstate Blue Forest (Sherwood) Green Patina Green l (Brite Red) l (Roman Blue) l (Regal Blue) Hartford Green Musket Gray l Colonial Red l Evergreen l Mansard Brown l Granite (Ash Gray) l PREMIUM COLORS Classic Copper (Penny) l Silver Metallic l Champagne Metallic l Zinc l 24 GA GALVALUME ONLY Regal White Surrey Beige Patrician Bronze Buckskin Charcoal * = Also in Mill Finish l l = Energy Star Rated Tremco receives metal through multiple vendors. If a specific metal vendor is required for a project, please specify this at the time of order. TREMCO Color Chart QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE Color 24 ga. 22 ga. .040” .050” .063” Please Note Almond w w w w w Tremco receives metal through Bone White w w w w w multiple vendors. If a specific metal Burgundy (Brandywine) w w w vendor is required for a project, please specify this at the time of Cardinal Red (Brite Red) w w w order. Charcoal w w w w Express colors available in shorter lead times for w w w w Cityscape 24 ga., .040” and .050” only. -

Chapter 9 Kiowa Ethnohistory and Historical Ethnography

Chapter 9 Kiowa Ethnohistory and Historical Ethnography ______________________________________________________ 9.1 Introduction Kiowa oral and recorded traditions locate their original homeland in western Montana near the headwaters of the Yellowstone River. Through a series of migrations east, the Kiowa settled near the Black Hills, establishing and alliance with the Crow. Closely associated with the Kiowa were the Plains Apache, who were eventually incorporated into the Kiowa camp circle during ceremonies. While living in the Black Hills, the Kiowa adopted the horse becoming mobile.1 The intrusion of the Cheyenne and Sioux forced the Kiowa southwest. Spanish sources place the Kiowa on the southern plains as early as 1732.2 However Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, in 1805, located the tribe living along the Platte River. Jedediah Morse, in his 1822 work, A Report to the Secretary of War of the United States on Indian Affairs also reported to Secretary of War John C. Calhoun that the Wetapahato or Kiawas were located “…between the headwaters of the Platte River, and the Rocky Mountains.”3 Through changing political and economic circumstances the Kiowa eventually established a homeland north of Wichita Mountains and the headwaters of the Red River.4 The forays into Spanish territory enabled them to acquire more horses, captives, slaves, and firearms. The acquisition of horses, either through raiding or trade, completely reshaped Kiowa society. Differences in wealth and status emerged, a leadership structure evolved that united Kiowa bands into a singular polity with shared tribal ceremonies and societies.5 Possibly as early as 1790, the Kiowa concluded an alliance with the Comanche.