Charter Schools: a Philadelphia Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

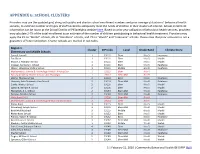

School Cluster List

APPENDIX G: SCHOOL CLUSTERS Providers may use the updated grid, along with public and charter school enrollment numbers and prior average utilization of behavioral health services, to estimate number and types of staff needed to adequately meet the needs of children in their clusters of interest. School enrollment information can be found at the School District of Philadelphia website here. Based on prior year utilization of behavioral health services, providers may calculate 2-7% of the total enrollment as an estimate of the number of children participating in behavioral health treatment. Providers may apply the 2% to “Model” schools, 4% to “Reinforce” schools, and 7% to “Watch” and “Intervene” schools. Please note that prior utilization is not a guarantee of future utilization. Charter schools are marked in red italics. Region 1 Cluster ZIP Code Level Grade Band Climate Score Elementary and Middle Schools Carnell, Laura H. 1 19111 Elem K to 5 Intervene Fox Chase 1 19111 Elem K to 5 Model Moore, J. Hampton School 1 19111 Elem K to 5 Model Crossan, Kennedy C. School 1 19111 Elem K to 5 Reinforce Wilson, Woodrow Middle School 1 19111 Middle 6 to 8 Reinforce Mathematics, Science & Technology II-MaST II Rising Sun 1 19111 Elem K to 4 Tacony Academy Charter School - Am. Paradigm 1 19111 Elem-Mid K to 8 Holme, Thomas School 2 19114 Elem K to 6 Reinforce Hancock, John Demonstration School 2 19114 Elem-Mid K to 8 Reinforce Comly, Watson School 2 19116 Elem K to 5 Model Loesche, William H. School 2 19116 Elem K to 5 Model Fitzpatrick, A. -

2013-‐2014 Learning Networks

2013-2014 Learning Networks NETWORK 1: Dion Betts, Assistant Superintendent Elementary Schools (K-5 and K-8) 24 Middle ScHools 1 High Schools 7 TOTAL 32 SOUTH PHILADELPHIA HIGH SCHOOL • Bregy, F. Amedee K-8 • Childs, George W. K-8 • Fell, D. Newlin K-8 o Jenks, Abram K-4 • McDaniel, Delaplaine K-8 • Southwark K-8 o Key, Francis Scott K-6 • Stanton, Edwin M. K-8 FURNESS HIGH SCHOOL • Jackson, Andrew K-8 • Kirkbride, Elizabeth B. K-8 • Meredith, William M. K-8 • Nebinger, George W. K-8 • Sharswood, George K-8 • Taggart, John H. K-8 • Vare, Abigail K-8 (@G. Washington El) BARTRAM HIGH SCHOOL • Comegys, Benjamin B. K-7 • Longstreth, William K-8 • Penrose K-8 • Tilden, William 5-8 o Catharine, Joseph K-5 • Mitchell, Weir K-6 o Morton, Thomas G. K-5 o Patterson, John M. K-4 MOTIVATION HIGH SCHOOL GAMP ACADEMY AT PALUMBO CAPA Arthur, Chester A. K-8 Girard, Stephen K-4 Note: PA = Promise Academy 1 2013-2014 Learning Networks NETWORK 2: Donyall Dickey, Assistant Superintendent Elementary Schools (K-5 and K-8) 20 Middle ScHools 2 High Schools 6 TOTAL 28 OVERBROOK HIGH SCHOOL • Beeber, Dimner 7-8 o Cassidy, Lewis C. K-6 o Gompers, Samuel K-6 o Overbrook Elementary K-6 • Heston, Edward K-8 • Lamberton K-8 • Overbrook Educational Center 1-8 • Rhoads, James K-8 SAYRE HIGH SCHOOL • Anderson, Add B. K-8 • Barry, Commodore John K-8 (PA) • Bryant, William Cullen K-8 (PA) • Hamilton, Andrew K-8 • Harrington, Avery K-7 • Huey, Samuel B. -

Brian Keech, Vice President Office of Government And

7828_OGCR_vMISSION:Layout 3 4/14/10 4:59 PM Page 2 BRIAN KEECH, VICE PRESIDENT OFFICE OF GOVERNMENT AND COMMUNITY RELATIONS DREXEL UNIVERSITY 3141 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104 215-895-2000 drexel.edu/admin/ogcr 7828_OGCR_vMISSION:Layout 3 4/14/10 4:59 PM Page 3 DREXEL UNIVERSITY COMMUNITY IMPACT REPORT 2010 Good Neighbors, Great Partners 7828_OGCR_vMISSION:Layout 3 4/14/10 4:59 PM Page 4 UNIVERSITY MISSION To serve our students and society through comprehensive integrated academic offerings enhanced by technology, co-operative education, and clinical practice in an urban setting, with global outreach embracing research, scholarly L Drexel students and neighbors alike enjoy the space and the views of the new Drexel Park, developed by the University on a former industrial site at 32nd Street and Powelton Avenue. activities, and community initiatives. 7828_OGCR_vMISSION:Layout 3 4/14/10 4:59 PM Page 1 FROM THE PRESIDENT Drexel has deep roots in our neighborhood, our city, our region and Pennsylvania. It is these roots that nurtured a university strong enough to develop a global reach and comprehensive aca- demics. Our success owes much to the vibrant “living laboratory” around us, and we are proud to pay that debt through ever-increasing service to our neighbors. Our expanding mission has created exciting new opportunities to engage our community. Drexel’s medical, nursing and public health programs provide vital care to local residents, especially the under- served. Our new Earle Mack School of Law has made pro bono legal work a centerpiece of its activities. Across Drexel, our students, faculty and staff are finding innovative ways to make a difference. -

Education Outreach Programs Annual Report 2018–19

Education Outreach Programs Annual Report 2018–19 PB THE BARNES FOUNDATION 2018–19 EDUCATION REPORT I Contents 2 About the Barnes 4 School Outreach Programs in Philadelphia and Camden 6 Look! Reflect! Connect! (Pre-K) 10 Pictures and Words (Grade 3) 13 Art of Looking (Grade 5–6) 16 Artist Voices (Grade 7) 19 Community Programming 19 Puentes a las Artes / Bridges to the Arts (Ages 3–5) 21 Additional Programming and Resources for Teachers and Students 21 Community Connections 22 STEAM Initiatives 24 High School Partnerships 25 Single-Visit Opportunities 25 Teacher Training 27 2018–19 Education Outreach Donors 28 Participating Schools Photos by Michael Perez, Sean Murray (p. 2) and Darren Burton (p. 19, 26) SECTION HEADER About the Barnes The Barnes Foundation was founded in 1922 by Dr. a teaching method that encouraged students to read Recent Highlights Albert C. Barnes “to promote the advancement of art as an artist does and to study its formal elements • Nearly 1.8 million visitors since 2012 education and the appreciation of the fine arts and of light, line, color, and space. Dr. Barnes wrote that horticulture.” As a nonprofit cultural and educa- his approach to education “comprises the observation • 240,000+ visitors in 2018 tional institution, the Barnes shares its unparalleled of facts, reflection upon them, and the testing of • 18,000+ member households in 2018 art collection with the public, organizes special the conclusions by their success in application. It exhibitions, and presents education and public pro- stipulates that an understanding and appreciation • 4 million+ online visitors engaged since the gramming that fosters new ways of thinking about of paintings is an experience that can come only launch of the new website in 2017 human creativity. -

15 Years of Arts Education & Advocacy

15 YEARS OF ARTS EDUCATION & ADVOCACY PICASSO PROJECT: 15 YEARS OF ARTS EDUCATION & ADVOCACY At Picasso Project, we believe that all 15 YEARS OF IMPACT: students deserve access to the arts. This core belief sparked Picasso Project’s inception 15 years ago, when PCCY and a group of concerned citizens 40,750 177 joined together in response to lack of adequate funding students inspired school-based arts for public educaiton and the resultant near elimination of through the arts projects funded arts education from Philadelphia’s public schools. By providing grants to support innovative arts projects in Philadelphia public schools, and advocating for equitable access to arts education, Picasso Project has played a critical role in assuring that Philly’s kids have access to high quality arts education. It is with great pride that we celebrate 15 years of Picasso 813 256 Project and share our story here. As we look back at our teachers initiated arts & community roots, we simultaneously look ahead towards new and innovative arts projects organizations exciting directions for Picasso Project. partnered for projects Tim Gibbon Picasso Project Director Public Citizens for Children and Youth 1 2003 In 2003, the Picasso Project began with support and engagement from the community. Pennsylvania had just completed a “Give Back” initiative in which citizens were sent back “excess” funds collected by the State. At the same time, “Reminding the arts were disappearing from the Philadelphia’s public schools due to lack people of the of funding. A group of concerned individuals, including Vicki Ellis, Lucinda Post, Dennis Barnebey, and Germaine Ingram met with PCCY leadership and launched importance the Give Back the Give Back Campaign to urge citizens to help support the arts of the arts in in our public schools by sending in their ‘Give Back” funds. -

FALL 2018 ADMISSIONS Table of Contents

HIGH SCHOOL DIRECTORY FALL 2018 ADMISSIONS Table of Contents Letter from the Superintendent ....................................................3 Mastbaum, Jules High School (CW) ...........................................42 Types of High Schools ................................................................... 4 Masterman, Julia R. High School (SA) .......................................43 High School Locations by Type ....................................................5 Motivation High School (SA) .......................................................44 School Progress Report ................................................................6 Northeast High School (NS)........................................................45 Purpose and Use: ...........................................................................6 Northeast Medical, Engineering and Aerospace Magnet (SA) .......................................................46 Performance Tiers .........................................................................6 Northeast Pre-International Baccalaureate SAMPLE ..........................................................................................6 Diploma Program (SA) .................................................................46 Academic and Specialty Programs .........................................7 - 8 Overbrook High School (NS) .......................................................47 All Academy High Schools ............................................................ 8 Parkway Center City Middle College (SA) -

05 Annual Rpt for Web.Indd

The Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education 2005 Annual Report Celebrating 40thOur OUR MISSION To promote, through environmental education, the preservation and improvement of our natural environment. We do this by: Fostering appreciation, understanding and responsible use of the ecosystem; Disseminating information on current environmental issues; Encouraging appropriate public response to environmental problems; Maintaining the facilities of the Center and conserving its land for the purpose of environmental education. 2 MESSAGE FROM THE BOARD CHAIR & EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR ur 40th anniversary year has been extraordinary! Celebrations throughout the year honored all those whose vision and hard work laid the foundation Ofor our current success. Sadly, we also paid our last respects to one of our founders, Henry H. H. Meigs, whose passing in February signified the end of an era. This milestone year has been marked by a renewed connection to our neighbors. A series of informal gatherings has strengthened relations, and the formation of the new Schuylkill Center Community Council has opened the door to ongoing dialogue about partnership efforts within the local community. Outside recognition from prominent local institutions brought validation for our efforts and commitment to environmental leadership. Our Education staff’s work with the Green Woods Charter School received commendation from the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, and our land restoration efforts garnered renewed funding from the Horace Acting Director, Dennis Burton (seated on left) and Goldsmith Foundation. We also received a substantial Board Chair, Harry Weiss (standing on right) with grant from the Pennsylvania Historical & Museum neighbors Mark Soffa, Brendan Binder and Ruth Ann Fitzpatrick celebrating the Center at a reception in the Commission. -

[email protected] Division of Food Services After School Programs

Division of Food Services Questions? Email: [email protected] After School Programs - Approval List Updated: 1/3/2019 Confirmed MEAL START Loc School Name Type FS Monitor Name Program Name Program schedule Enrollment DATE 444 ALLEN, DR. ETHEL SCHOOL SAT_R LS Bruce Harvey Girl Scouts, Dr. Ethel Allen Girl Scouts 21 Monday, Tuesday 9/24/2018 444 ALLEN, DR. ETHEL SCHOOL SAT_R LS Bruce Harvey Salvation Army, 21st Century 31 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 9/24/2018 444 ALLEN, DR. ETHEL SCHOOL SAT_R LS Bruce Harvey PhiladelphiaOIC-OST 19 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 10/1/2018 Episcopal Community Services, ECS 146 ANDERSON, ADD B. SCHOOL SAT_P BD Yvette Herrington OST @ Anderson 92 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 9/4/2018 146 ANDERSON, ADD B. SCHOOL SAT_P BD Yvette Herrington Harlem Lacrosse - Philadelphia 19 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 10/1/2018 Sunrise of Philadelphia Inc., Sunrise 248 ARTHUR, CHESTER A. SCHOOL SAT_P KC Barbara Bauhof Afterschool at Chester A Arthur 85 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 9/4/2018 221 BACHE-MARTIN SCHOOL SAT_P KA Nikia Davenport Extended Day 55 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 9/17/2018 120 BARRY, JOHN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL FS DS Yvette Herrington Change 4a dollar 24 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 11/21/2018 720 BARTON SCHOOL SAT_P KA George Clay Young Achievers Learning Center 50 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 8/29/2018 Public Health Management Corporation, 101 BARTRAM, JOHN HIGH SCHOOL FS DS Yvette Herrington Project Lyft 41 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 11/7/2018 751 BETHUNE, MARY MCLEOD SCHOOL SAT_R JL Bruce Harvey PAEP, STEAM After-School Program 30 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday 10/1/2018 751 BETHUNE, MARY MCLEOD SCHOOL SAT_R JL Bruce Harvey City Year 36 Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday 10/9/2018 Intergenerational Center, Grandma's 422 BLAINE, JAMES G. -

Computer Support Specialists IT Apprenticeship Program

Computer Support Specialist Locations 2011 - 2012 Academy at Palumbo Bache-Martin Elementary School Communications Technology High School What’s being said about the Murrell Dobbins High School Computer Support Specialists Thomas A. Edison High School Samuel Fels High School program: Thomas Fitzsimons High School Computer Support Frankford High School “This is a great program. By having an on-site technician, Franklin Learning Center we are able to be more productive and integrate our Specialists IT Benjamin Franklin High School technology better within the school.” High School of the Future Apprenticeship Program Kensington Business Principal William Loesche Elementary School Martin Luther King High School The Computer Support Specialist program Jules E. Mastbaum High School is designed to meet the demand for full-time Julia R. Masterman High School Motivation High School technology support staff for teachers and students. Northeast High School Overbrook High School The Computer Support Specialist program Parkway Center City High School offers School District of Philadelphia graduates Philadelphia High School for Business who are interested in technology careers the Philadelphia Learning Academy South Randolph Technical High School opportunity to gain technical skills and utilize them Roxborough High School in Philadelphia high schools. Science Leadership Academy South Philadelphia High School The Computer Support Specialist program Strawberry Mansion High School West Philadelphia High School is a School District of Philadelphia initiative in partnership with Communities In Schools of Philadelphia, Inc. The CSS Program is managed by the Registered with the Pennsylvania School District’s Office of Educational Technology. Department of Labor utp-philly.org Creating Future Technology Leaders Committing to the Future The School District of Philadelphia and Communi- What is next for the Computer Support Specialist ties In School of Philadelphia, Inc. -

Questions? E-Mail: [email protected] Division of Food Service Updated :9/25/2017 After School Programs- Approval List

Questions? E-mail: [email protected] Division of Food Service Updated :9/25/2017 After School Programs- Approval List Confirmed Enrollment. Authorized # for Loc type FS School Name Program Name Meal Delivery Program schedule Meal Start Date 101 FS DS BARTRAM, JOHN HIGH SCHOOL Athletic Enrichment 43 Friday 9/29/17 102 FS DS WEST PHILADELPHIA HIGH SCHOOL Netter Center for Community Partnerships- UPENN 120 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 9/11/17 110 FS BD SAYRE, WILLIAM L. HIGH SCHOOL The Netter Center for Community Partnerships 50 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 9/11/17 113 FS BD TILDEN MIDDLE SCHOOL Project L.Y.F.T (Stem N2 Action) 38 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 10/2/17 120 FS DS BARRY, JOHN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL Change 4 a Dollar Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 123 SAT BD BRYANT, WILLIAM C. SCHOOL theVillage 22 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 9/25/17 123 SAT BD BRYANT, WILLIAM C. SCHOOL theVillage 0 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 125 SAT BD CATHARINE, JOSEPH SCHOOL theVillage 50 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 9/25/17 126 FS BD COMEGYS, BENJAMIN B. SCHOOL Netter Center For Community Partnerships 95 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 9/12/17 129 SAT DS HAMILTON, ANDREW SCHOOL WES OST program 80 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 9/11/17 134 SAT DS LEA, HENRY C. University-Assisted Community Schools After-school Enrichment Program 45 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 9/11/17 134 SAT DS LEA, HENRY C. Whiz Kidz 77 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 9/25/17 135 SAT BD LONGSTRETH, WILLIAM C. -

Virtual Graduation Ceremony

Virtual Graduation Class of 2020 Ceremony Class of 2020 Graduation Program Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance No. 1 - The Philadelphia Orchestra National Anthem - Saleka Superintendent Remarks - Dr. William R. Hite, Jr. Student Remarks - Doha Ibrahim, senior, Abraham Lincoln High School Original Song: Graduation - Saw Tar Thar Chit Ba, senior, Horace Furness High School Mayoral Remarks - Mayor Jim Kenney Student Remarks - Imere Williams, senior, Boys’ Latin Charter School Original Spoken Word: We Made It - Hailey Molina, senior, Philadelphia High School for Girls Keynote Address - Malcolm Jenkins 20 for 20: A Citywide Tribute for 1 p.m. - Brian Dawkins In Memoriam Turning of the Tassel - Superintendent William R. Hite, Jr. Student Remarks - Juliet Dempsey, senior, Arts Academy at Benjamin Rush Original Song: Only The Beginning - Jalyn Tabourn, senior, Franklin Learning Center Special Gift for Class of 2020 - Malcolm Jenkins Closing Scroll - senior names by high school (alphabetical order) Masters of Ceremony: Bob Kelly Cappuchino Anyea Lachelle Fox29 News Power 99 iHeart Media NBC 10’s Philly Live Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance No. 1 - The Philadelphia Orchestra National Anthem Superintendent Remarks Student Remarks Saleka Dr. William R. Hite, Jr. Doha Ibrahim, senior, Abraham Lincoln HS Saw Tar Thar Chit Ba With all we’ve learned senior, Horace Furness High School Throughout 4 years Original Song: Graduation And I will say We’ve earned it So now let’s celebrate it Time has arrived And start our own big visions We all know one day we will be -

Cover Page for Assessment Resource

Cover Page for Assessment Resource Department Institutional Research Submitting Report: Brief Description of Report/Document: Community College of Philadelphia Placement for Recent High School Graduates from Philadelphia Area High Schools, Fall 2011 Institution Wide Assessment Committee 3/21/2012 Fall 2011 Semester Community College of Philadelphia Placement for Recent High School Graduates from Philadelphia Area High Schools * Recent HS Placed Dev Percent Placed Placed Dev Percent Placed Placed Dev Percent Placed HS Category HS Graduates Writing Dev Writing Reading Dev Reading Math Dev Math Neighborhood Abraham Lincoln High School 50 42 84.0% 37 74.0% 31 62.0% Neighborhood Benjamin Franklin High School 20 19 95.0% 17 85.0% 9 45.0% Neighborhood Charles Carroll High School 10 10 100.0% 9 90.0% 6 60.0% Neighborhood Edison-fareira High School 30 29 96.7% 24 80.0% 20 66.7% Neighborhood Frankford High School 28 24 85.7% 21 75.0% 18 64.3% Neighborhood George Washington High School 64 46 71.9% 40 62.5% 27 42.2% Neighborhood Germantown High School 21 18 85.7% 17 81.0% 15 71.4% Neighborhood Horace Howard Furness High School 19 12 63.2% 11 57.9% 12 63.2% Neighborhood John Bartram High School 22 18 81.8% 17 77.3% 19 86.4% Neighborhood Kensington Capa 10 9 90.0% 9 90.0% 7 70.0% Neighborhood Kensington Culinary Arts 3 1 33.3% 1 33.3% 0 0.0% Neighborhood Kensington High School 2 2 100.0% 2 100.0% 1 50.0% Neighborhood Kensington International Business 11 10 90.9% 9 81.8% 7 63.6% Neighborhood Martin Luther King High School 20 16 80.0% 15 75.0% 14 70.0%