Furling Gear and Trailers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Feel the Need…

44 AUSTRALIAN SAILING AUGUST-SEPTEMBER 2017 MYSAILING.COM.AU 45 SPORTSBOATS BETH MORLEY SPORTSAILINGPHOTOGRAPHY.COM SPORTS BOATS I FEEL THE NEED… ANDREW YORK LOOKS AT THE DEVELOPMENT OF SPORTSBOATS AND HOW THEY NEED TO BE SAILED IT was in the early years of this century that sports boats broke away from their trailer-sailer forebears. A more competitive group of owners started adding sail area and stripping out accommodation from their boats. Most people’s perception of a sports boat is a trailerable sailing boat with masses of sail area. While this was the genesis of sports boats there has been a gradual change. It became evident that sports boats needed to form their own separate group. ASBA was founded in 2007 by Cameron Rae, Mark Roberts and Richard Parkes. They wanted a more scientific handicapping system than had been employed in the past. In 2008 the Sportsboat Measurement System (SMS) was put in place by a body independent to ASBA. It was created by the same people who formulated the Australian Measurement System (AMS) in 1997. Sports boat racing has flourished across Australia under the ASBA banner, with the SMS rule encouraging high performance designs without the penalties that existed under other systems. Large asymmetrical spinnakers, in particular, are not penalised as harshly in the rating as the working sail area is, so that is why you see the sports boats with clouds of sails downwind. In Australia sports boats are defined as being between 5.8m and 8.5m in length and no more than 3.5m wide including hiking racks. -

CYCA-Annual-Report-2003-04.Pdf

2003 2004 Cruising Yacht Club of Australia Annual Report Cruising Yacht Club of Australia Board of Directors 2003 – 2004 Back row left to right: Front row left to right: L. Goodridge Rear Commodore M. James M. Cranitch Vice Commodore G. Lavis R. Skellet Commodore J. Messenger G. Linacre Rear Commodore R. Hickman M. Allen G. Swan Treasurer A. Green Photo: Ian Mainsbridge CONTENTS Board of Directors, Management and Sub-Commitees 2 Associate Committee Report 16 Membership No.’s, Life Members, Past Commodores Directors’ Report 17 and Obituary 3 Independent Audit Report 22 Commodore’s Report 4 Directors’ Declaration 23 Treasurer’s Report 5 Statement of Financial Performance 24 Audit, Planning & Risk Committee Report 7 Statement of Financial Position 25 Sailing Committee Report 8 Statement of Cash Flows 26 Training & Development Committee Report 10 Notes to the Financial Statements 27 CYCA Cruising Report 12 Disclaimer 43 Marina & Site Committee Report 13 Supplementary Information 44 Member Services Committee Report 14 Members List 45 Archives Report 15 CYCA Yacht Register 54 Cruising Yacht Club of Australia Annual Report: year end 31 March 2004 1 2003-2004 Board of Directors Commodore J. C. Messenger Vice Commodore G. R. Lavis Rear-Commodore R. J. Hickman and M. R. James Treasurer A. Green Directors M. Allen, M. Cranitch, L. Goodridge, G. Linacre, R. Skellet, G. Swan Management Assistant to Chief Executive Officer C. Del Conte Accountant N. McKinnon Sailing Manager J. Kirkjian Operations Supervisor A. Payne Youth Sailing Academy Manager/Coach J. Bonnitcha Communications Manager L. Ratcliff Duty Manager M.Gibson Sub-Committees Archives R. Skellet (Chairman), B. -

The Sailing Magazine for the Rest of Us

The sailing magazine for the rest of us. 10 00 00 $8 (Canada $8 CDN) 10 0 62825 97035 7 goodoldboat.com Issue 128 September/October 2019 Automatic/Manual Inflatable PFD USCG Approved Type V with Type II Performance! Full 35 lbs buoyancy! Comfortable, low profile, with wide neoprene neckline. Universal sizing, fits 30"-65" chest. Hi-Vis inflation chamber. Durable 400 denier nylon. Super bright retro-reflective areas on front and a high-visibility BEACON logo on the back. H Reg 179.99 HAMILTON SAVE $ 99 $30 NEW! 149 ea Pre-order MARINE Part# Color Order# ™ HMI-BCNI35OG Orange/Gray 773536 today! HMI-BCNI35BG Blue/Light Gray 773535 BOATERS' STORE! Moisture Absorber Dries air in cabins, lockers, closets, rooms, basements and other enclosed State-of-the-art line areas. Super-dry concentrated pellet of premium coatings, formula absorbs up to 50% more adhesives and putties. moisture than flake formulas. Search# SYT- $ 29 7 ea MK-6912 Order# 144114 Hamilton Wayne Photo by Tea Tree Power® Mold & Mildew Eliminator Non-toxic, bio-degradable. Blended from 100% Australian tea tree oil. Available in gel or spray. Tarps Starting At • Lightweight Blue 3 GRADES, $ 99 • Premium White 27 SIZES! 17 ea • Super Heavy Duty Silver HAMILTON Search# FOR-77020 Search# STT- Premium 7 Mil. White Oil Absorbent Sheets Shrink Wrap Each 15" x 19" sheet CAN HELP! absorbs 13 to 25 times Some sizes are available its weight in oil, fuel Many Hamilton Marine employees maintain in clear and blue. Shrink and other hydrocar- their own boats. And there is no better teacher wrap accessories are also bons. -

Sailing a Dabber Owning a Drifter Tim Severin

DDRASCOMBEA ASSOCIATIONN NEWS www.drascombe-association.org.uk DDRASCOMBEA ASSOCIATIONN NEWS No. 136 • Spring 2021 Sailing a Dabber Owning a Drifter Tim Severin SAMPLE EDITION Netherlands Ireland Italy Association Business Association Business The Association Shop Association Items Drascombe Association News Spring 2021 • No.136 The magazine of the Drascombe Owners’ Association Do you have an article for DAN? Car Sticker Please read this first! Contents Badge Boat Sticker Burgee Cloth Badge We love receiving your articles and would appreciate your Association Business help in getting them printed in DAN. Just follow these simple rules: Who’s Who 4 Chaiman’s Log 4 Length – try to keep to 1500 words; but we can split New Members 5 longer artlicles over two issues. Editor 6 Rally Programme 7 Tie Tea Towel Format – Unformatted Word Document (not pdf or typed onto an email, each of which require retyping or Rally Form 10 Mugs Knitted Beanie reformatting). Photo Competition 12 Committee News 13 Burgee Tan Lugger on cream, supplied with toggle and eye £15.50 Photos – please: Drascombe Mug features the Dabber, Lugger & Coaster. By Bob Heasman £8.00 • Provide captions or explanations; Regular Features Knitted Beanies Navy with Bronze Lugger logo. One size fits all £9.50 • Tell us who took them; News from the Netherlands 14 Lapel Pin Badge Metal enameled Drascombe Lugger £4.00 • Send as separate, high resolution, jpg files; Tim Severin - Obituary 15 Drascombe Car Sticker “Drascombe – the sail that becomes a way of life” £1.50 • Do not send me links to websites – photo quality will Junior DAN 16 Drascombe Boat Sticker. -

Pint Sized Low Water Drifter

Pint sized Low water Drifter This neatly designed trailer-sailer’s traditional looks and easy handling impressed Sam Fortescue rascombes have had classic look to them – hard chines in something of a split the hull, wooden spars, tan sails and personality since the a bowsprit and bumkin. She has a licence to use the name gentle sheer with a nice iroko toerail Dparted company from and rubbing strake. Her relatively the original moulds. high cabin top and cockpit coaming hese last are owned by Honnor give her a sturdy look. Marine, which produces its Devon In fact Stewart says she’ll heel to Originals line of luggers, while 72° before water laps over the side. Churchouse Boats in Hampshire owns We couldn’t test this in the gentle a later set of moulds (which it claims 8-10 knots on ofer in Chichester are better) and the Drascombe name. Harbour, but she should self-drain he very irst Drascombe was a 19t into the outboard well, as the cockpit (5.7m) lugger designed by John sole is above the water. Another nice Watkinson in 1968 and built in ply. touch is the fold-up washboard, which He took the boat to the London Boat battens down to the sole when not in Show, where it sold 12 times over, use, but hinges up to help keep water and he began producing glassibre out of the cabin on a sploshy day. versions the following year. More designs were launched, including the Simple interior 21t 6in (6.6m) Driter in 1987. Below, she is designed to a budget, but A few decades later and over 5,000 well thought through and Churchouse examples of Watkinson’s designs have will it her out to any speciication. -

Auction List 2019

Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum Charity Boat Donation Program 2019 Charity Auction August 31, 2019 See Photos and more info:bitly.com/buyaboat From luxury boats to dinghies, CBMM accepts and sells donated boats all year-round. 213 N. Talbot St., St. Michaels, MD 21663 410-745-4942 [email protected] Inv. # ***BOATS IN THE WATER ARE LISTED SEPARATELY AT THE END*** Trailer TREAD LIGHTLY YAWL. The ultimate pocket cruiser from the design board of John Welsford, similar to the more well known Scamp. Custom built to very nice 5213 Y/U standards and fully rigged and ready. Very good untitled storage trailer included. Untitled, unregistered small craft not intended for motorization. 1978 Cobalt Bowrider 19 with a Replaced 5 litre GM V-8 sterndrive. 2017 USCG 6005 safety inspection sticker. Runs well, electric shift, new upper outdrive, new lower Y/T outdrive, new prop. 9.9 hp Evinrude kicker motor and transom mount. Beautiful Cedar Strip rowing dinghy with sail rig. Would be a fun rowing dinghy for 6016 an adult or sailing dinghy for a kid. N 1980 North American Spirit 21 with titled trailer. Boat is in good overall condition. 6018 Sails and rigging are in good shape. Titled galvanized trailer and Nissan 5 HP Y/T outboard included. Great trailer sailer. 1988 18' Ebbtide Campione Bow Rider. 150 HP Mercury Engine that runs. great 6030 Y/U boat for skiing, tubing or just cruising. Sitting on a nice trailer 1987 Foli Star boat. She is in good overall condition with the expected wear and 6039 Y/T tear for her age and comes with a nice trailer with storage lockers. -

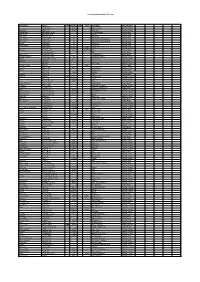

C:\Boatlists\Boatlistdraft-2021.Xlsx Boat Name Owner Prefix Sail No

C:\BoatLists\boatlistdraft-2021.xlsx Boat Name Owner Prefix Sail No. Suffix Hull Boat Type Classification Abraham C 2821 RS Feva XL Sailing Dinghy Dunikolu Adams R 10127 Wayfarer Sailing Dinghy Masie Mary Adlington CPLM 18ft motorboat Motor Boat Isla Rose Adlington JPN Tosher Sailing Boat Demelza Andrew JA 28 Heard 28 Sailing Boat Helen Mary Andrew KC 11 Falmouth Working Boat Sailing Boat Mary Ann Andrew KC 25 Falmouth Working Boat Sailing Boat Verity Andrew N 20 Sunbeam Sailing Boat West Wind Andrew N 21 Tosher 20 Sailing Boat Andrews K 208210 white Laser 4.7 Sailing Dinghy Hermes Armitage AC 70 dark blue Ajax Sailing Boat Armytage CD RIB Motor Boat Alice Rose Ashworth TGH Cockwell's 38 Motor Boat Maggie O'Nare Ashworth TGH 10 Cornish Crabber Sailing Cruiser OMG Ashworth* C & G 221 Laser Pico Sailing Dinghy Alcazar Bailey C Motor Boat Bailey C RS Fevqa Sailing Dinghy Dither of Dart Bailey T white Motor Sailer Coconi Barker CB 6000 Contessa 32 Sailing Cruiser Diana Barker G Rustler 24 Sailing Boat Barker G 1140 RS200 Sailing Dinghy Gemini Barnes E RIB Motor Boat Pelorus Barnes E GBR 3731L Arcona 380 Sailing Cruiser Barnes E 177817 Laser Sailing Dinghy Barnes F & W 1906 29er Sailing Dinghy Lady of Linhay Barnes MJ Catamaran Motor Boat Triumph Barnes MJ Westerly Centaur Sailing Cruiser Longhaul Barstow OG Orkney Longliner 16 Motor Boat Barö Barstow OG 2630 Marieholm IF-Boat Sailing Cruiser Rinse & Spin Bateman MCW 5919 Laser Pico Sailing Dinghy Why Hurry Batty-Smith JR 9312 Mirror Sailing Dinghy Natasha Baylis M Sadler 26 Sailing Cruiser -

Elliott 22 Day Sailer Sweet Little Lies Shaping a Dream

& ' ( % BOAT REVIEWS FEATURES NEWS READ MAG DIRECTORY VIDEOS SUBSCRIBE FEATURES LATEST ARTICLES $% SHAPING A DREAM by Boating New Zealand ! JANUARY 30, 2020 BOAT WORLD ! APRIL 7, 2020 FREE DIGITAL MAGAZINE FOR BOAT WORLD HOUSE-BOUND FISHERS LOCKDOWN DELIVERIES Your accountant, partner and gol0ng friends will all tell you that with boats, chartering is better than buying, and buying second-hand rather than building is common sense. But common sense can be very unsatisfying, writes Stewart Halliwell. The idea of building a boat is like a cloud that hangs over you until it’s done. I’d built a Canadian canoe and a Phase 2 yacht in GRP and worked in the GRP supply business. I was a passionate sailor and had crewed on numerous racing yachts. I’d previously owned a Laser and a Whiting 16 trailer-sailer. But the desire to build a unique yacht – my yacht – was always there. I’d met designer Greg Elliot a couple of times – once on his boat Party Pro – reverse sheer, big cockpit with side trenches and a cavernous (mostly empty) interior. Inside and out, this yacht looked like no other. Over a few beers he shared his ideas on design – a key one being that a yacht should sail on, not through the water. Advertisement FACEBOOK Boating New Z… 5.1K likes Like Page Fast forward a few decades. The empty nest syndrome had reignited the building-a-yacht idea. I liked the simplicity and backyard accessibility of the Hartley 16, Mullet boats and the Pied Piper – but thought it best to distill these classics into a modern design equivalent. -

2018 Charity Boat Auction Inventory Thank You for Your Generous

Thank you for your generous support of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum ! 2018 Charity Boat Auction Inventory INV # DESCRIPTION TYPE MACGREGOR 26. 1987. Iconic trailerable weekender w/ 9.9 hp Honda 4 stroke o/b motor and good tandem axle 5009 untitled storage trailer. Fantastic bay and inland cruiser for most anywhere you can haul and launch her. Sea Sail of Cortez anyone ? Untitled storage trailer included. MD 6620 CH. CURRENT DESIGNS FITNESS KAYAK. Freedom model. 18 ft. long and 21 3/4 beam. Only 33 lbs. ! Kevlar 5019 construction with rudder and adjustable seat. As new condition . No paddle. Untitled, unregistered smallcraft not Paddle intended for motorization. AMF SUNFISH. 1969 Original owner boat used exclusively on fresh water lake in PA. Green stripe and splash 5031 guard. Well cared for and complete boat ready for more fun. Everyone loves a Sunfish. Why not treat yourself or Sail your kids to one. Untitled, unregistered smallcraft not intended for motorization. MISTRAL WINDSURFER. Really nice condition! Mast, boom, two sails (one brand new!), and sailbag included. 5038 Sail Untitled, unregistered smallcraft. BOMBARDIER SEADOO CHALLENGER 1800. 1997 twin Rotax water jet sport boat with bimini top. Motors need 5045 attention / replacement, jet pumps appear sound. Good project / parts boat, or buy it for the very nice galvanized, Power titled Sea Doo trailer. MD 3421 BJ. CAPE COD SENIOR KNOCKABOUT. Beautiful 23 ft. Spaulding Dunbar design built by Cape Cod Shipbuilding 1940's. Graceful c/b sloop with large cockpit and simple rig. Quite similiar to a Sakonnet 23 with a counter stern, W Class 22, Hodgon 21, etc.. -

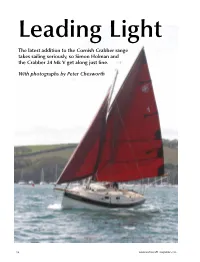

The Latest Addition to the Cornish Crabber Range Takes Sailing Seriously, So Simon Holman and the Crabber 24 Mk V Get Along Just Fine

Leading Light The latest addition to the Cornish Crabber range takes sailing seriously, so Simon Holman and the Crabber 24 Mk V get along just fine. With photographs by Peter Chesworth 14 www.watercraft-magazine.com eating out of Mylor Harbour on a grey and blustery crabbers worked out of coves and porths under sail and spring day, we pass an elegant Sigma 33 lying to oar. These versatile open boats, typically around 20' (6m), Bher mooring. Pressing on in the drizzle, we tack past were primarily inshore potting boats, light enough to be a Cornish Yawl, a Crabber 26, several of the ever-popular worked by one or two men from a beach but robust enough Shrimpers and finally one of Cockwell's Duchy launches. You in construction to handle a range of conditions and fishing could be forgiven for thinking this had all been planned, given activities. A hundred years ago most small Cornish harbours our crew. We are sailiing Cornish Crabbers' new Crabber 24 would have had a dozen or more crabbers. Mk V, joined by Peter Thomas, managing director of Cornish With the advent of power the boats got bigger and their Crabbers and her designer, Andrew Wolstenholme. ports and usage changed. But by the 1970s modern leisure It’s a rare treat to meet a designer whose work I’ve long interpretations of traditional working craft were appearing admired but happily this is not the first time it has happened. on the market. In his 1983 book Working Boats of Britain, At university, I was fortunate to meet the late David Thomas, Eric McKee wrote: “To give some recent examples…Westerly who generously lent me some designs for a project I was Boats are building a 24' topsail gaff cutter.. -

Drascombe Association News

DDRASCOMBEA ASSOCIATIONN NEWS www.drascombe-association.org.uk DDRASCOMBEA ASSOCIATIONN NEWS No. 125 • Summer 2018 Longboat at 34ºS Shannon Raid Harwich to Whitby In Tasmania What Safety Kit? Junior Restoring Photo DAN Victory Competition The Association Shop Drascombe Association News Association Items Summer 2018 • No.125 The magazine of the Drascombe Owners Association BURGEE Tan Lugger on cream supplied with toggle and eye. 15 inches wide £15.50 TIES in navy or brown with Drascombe motif £5.00 Knitted Beanies navy with bronze Lugger logo. One size fits all £9.50 Lapel Pin Badge Metal enamelled Drascombe Lugger £4.00 Do you have an Contents Drascombe Car Sticker “Drascombe – the sail that becomes a way of life” £1.50 three for £3.50 article for DAN? Association Business Drascombe Boat Sticker “Drascombe Association Member” £1.25 Please read this first! Who’s Who 4 three for £2.50 We love receiving your articles and would appreciate your Drascombe Association Badge (washable) suitable for jeans, sweaters, etc £3.00 help in getting them printed in DAN. Just follow these Chaiman’s Log 5 Drascombe Association Tea Towel Displays 9 detailed images of the most popular Drascombes. simple rules: Membership News 5 100% cotton and machine washable. Use it or frame it. £5.95 Length – maximum 1500 words; no minimum. Rally Programme 6 Books to Buy Format – Unformatted Word Document (not pdf or Editorial 9 typed onto an email, both of which require retyping or Drascombe 10/30 10 years of the Association and 30 years of Drascombes £5.00 reformatting). -

YARDSTICKZAHLEN 2021 Inklusive Einführung in Das System Und Regeln

Aktualisierung: Januar 2021 YARDSTICKZAHLEN 2021 Inklusive Einführung in das System und Regeln 4531279 Informationen für Mitglieder des Deutschen Segler-Verbands Aktualisierung: Januar 2021 YARDSTICKZAHLEN 2021 Inklusive Einführung in das System und Regeln HIGH GLOSS — DURABLE & REPAIRABLE — TRUE COLOR NEXT GENERATION TOPCOAT 45 1279 awlgrip.com 3 facebook.com/awlgripfinishes twitter.com/awlgrip instagram.com/awlgripfinishes All trademarks mentioned are owned by, or licensed to, the AkzoNobel group of companies. Informationen für Mitglieder des Deutschen Segler-Verbands © AkzoNobel 2021. 9861/0121 IPL0121879480-001_Awlgrip_HDT_IT_105x148.indd 1 22/01/2021 10:46 Yardstick Deutschland Yachten desselben Serientyps, für die eine YS-Zahl gilt, müssen Von Dietrich Kralemann also dieselben Konstruktionsmerkmale des Rumpfes (Tiefgang, Motorausrüstung, Verdrängung, Kielgewicht, Kielform und -mate- Motto: Fair segeln, mit fairen Mitteln gewinnen! rial u. ä.) und denselben Ausrüstungsstandard von Rigg und Segeln aufweisen. 1. Allgemeine Zielsetzungen Bei den vom DSV anerkannten Klassen und Werftklassen gibt es in Der DSV beabsichtigt mit dem von ihm propagierten und jährlich dieser Hinsicht keine Probleme. aktualisierten Yardsticksystem, das Regattasegeln mit baugleichen Aber auch für die übrigen Serienyachten ist der Standard durch De- Serienyachten und Jollentypen zu fördern. finition und Beschreibung im YS-Grundstandard verbindlich festge- Dabei sollen zeitlicher und finanzieller Vermessungsaufwand für legt. Für den Rumpf sind Kielform, ggf.