Regulating Rap Music: It Doesn't Melt in Your Mouth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

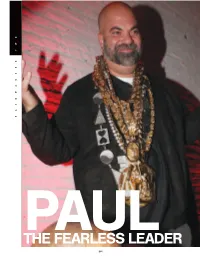

The Fearless Leader Fearless the Paul 196

TWO RAINMAKERS PAUL THE FEARLESS LEADER 196 ven back then, I was taking on far too many jobs,” Def Jam Chairman Paul Rosenberg recalls of his early career. As the longtime man- Eager of Eminem, Rosenberg has been a substantial player in the unfolding of the ‘‘ modern era and the dominance of hip-hop in the last two decades. His work in that capacity naturally positioned him to seize the reins at the major label that brought rap to the mainstream. Before he began managing the best- selling rapper of all time, Rosenberg was an attorney, hustling in Detroit and New York but always intimately connected with the Detroit rap scene. Later on, he was a boutique-label owner, film producer and, finally, major-label boss. The success he’s had thus far required savvy and finesse, no question. But it’s been Rosenberg’s fearlessness and commitment to breaking barriers that have secured him this high perch. (And given his imposing height, Rosenberg’s perch is higher than average.) “PAUL HAS Legendary exec and Interscope co-found- er Jimmy Iovine summed up Rosenberg’s INCREDIBLE unique qualifications while simultaneously INSTINCTS assessing the State of the Biz: “Bringing AND A REAL Paul in as an entrepreneur is a good idea, COMMITMENT and they should bring in more—because TO ARTISTRY. in order to get the record business really HE’S SEEN healthy, it’s going to take risks and it’s going to take thinking outside of the box,” he FIRSTHAND told us. “At its height, the business was run THE UNBELIEV- primarily by entrepreneurs who either sold ABLE RESULTS their businesses or stayed—Ahmet Ertegun, THAT COME David Geffen, Jerry Moss and Herb Alpert FROM ALLOW- were all entrepreneurs.” ING ARTISTS He grew up in the Detroit suburb of Farmington Hills, surrounded on all sides TO BE THEM- by music and the arts. -

United States District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania

Case 2:08-cv-01327-GLL Document 8 Filed 11/26/08 Page 1 of 3 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA ZOMBA RECORDING LLC, a Delaware limited liabiHty company; ELECTRONICALLY FILED BMG MUSIC, a New York general partnership; INTERSCOPE RECORDS, a Califorma general partnership; UMG CIVIL AcrION NO. 2:08-cv-01327-GLL RECORDINGS, INC., a Delaware corporation; and WARNER BROS. RECORDS INC., a Delaware corporation, Plaintiffs, vs. ClARA MICHELE SAURO, Defendant. DEFAULT .JUDGMENT AND PERMANENT IN,JUNCTION Based upon Plaintiffs' Motion For Default Judgment By The Court, and good cause appearing therefore, it is hereby Ordered and Adjudged that: 1. Plaintiffs seek the minimum statutory damages of $750 per infringed work, as authorized under the Copyright Act (17 U.S.c. § 504(c)(1», for each of the ten sound recordings listed in Exhibit A to the Complaint. Accordingly, having been adjudged to be in default, Defendant shall pay damages to Plaintiffs for infringement of Plaintiffs' copyrights in the sound recordings listed in Exhibit A to the Complaint, in the total principal sum of Seven Thousand Five Hundred Dollars ($7,500.00). 2. Defendant shall further pay Plaintiffs' costs of suit herein in the amount of Four Hundred Twenty Dollars ($420.00). Case 2:08-cv-01327-GLL Document 8 Filed 11/26/08 Page 2 of 3 3. Defendant shall be and hereby is enjoined from directly or indirectly infringing Plaintiffs' rights under federal or state law in the following copyrighted sound recordings: • "Cry Me a River," on album "Justified," -

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life. -

Social Adversity Portrayed by Tupac and Eminem

Social adversity portrayed by Tupac and Eminem Written by: HIP HOP PSYCH Co-Founders Dr Akeem Sule & Dr Becky Inkster Published: 5th October 2015 Tupac Shakur and Eminem are often touted as two of the greatest rappers of all time. Whilst Tupac is African American and Eminem is Caucasian, their lyrics have similar narrative story telling styles that are filled with anguished suffering, anger and other emotional tones conveyed in their hip-hop songs. Two songs that describe important issues of adversity reflecting strong emotional turmoil in their lyrics includes the songs, ‘Death around the corner’ from Tupac Shakur’s album, ‘Me Against The World’, and ‘Cleaning out my closet’ by Eminem from his album, ‘The Eminem Show’. In this article, we dissect the lyrics for psychopathological themes and we use the biopsychosocial model to explore the underpinnings of the emotional turmoil experienced by these two characters. In the song, ‘Death around corner’, Tupac’s character is preoccupied with paranoia about a perceived threat to his own life as well as to his family’s life. He feels the need to protect himself and his family from perceived targeted violence. Straight away, the song opens with a skit. It is a dialogue between Tupac’s character, his partner, and their son. Tupac’s character is standing by the window with a firearm (i.e., an ‘AK’, abbreviated for AK-47). His son is confused about his father’s strange behaviour and his wife is exasperated with her partner HIP HOP PSYCHTM COPYRIGHT © 2015 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED and feels he is consumed by his paranoia. -

Eminem 1 Eminem

Eminem 1 Eminem Eminem Eminem performing live at the DJ Hero Party in Los Angeles, June 1, 2009 Background information Birth name Marshall Bruce Mathers III Born October 17, 1972 Saint Joseph, Missouri, U.S. Origin Warren, Michigan, U.S. Genres Hip hop Occupations Rapper Record producer Actor Songwriter Years active 1995–present Labels Interscope, Aftermath Associated acts Dr. Dre, D12, Royce da 5'9", 50 Cent, Obie Trice Website [www.eminem.com www.eminem.com] Marshall Bruce Mathers III (born October 17, 1972),[1] better known by his stage name Eminem, is an American rapper, record producer, and actor. Eminem quickly gained popularity in 1999 with his major-label debut album, The Slim Shady LP, which won a Grammy Award for Best Rap Album. The following album, The Marshall Mathers LP, became the fastest-selling solo album in United States history.[2] It brought Eminem increased popularity, including his own record label, Shady Records, and brought his group project, D12, to mainstream recognition. The Marshall Mathers LP and his third album, The Eminem Show, also won Grammy Awards, making Eminem the first artist to win Best Rap Album for three consecutive LPs. He then won the award again in 2010 for his album Relapse and in 2011 for his album Recovery, giving him a total of 13 Grammys in his career. In 2003, he won the Academy Award for Best Original Song for "Lose Yourself" from the film, 8 Mile, in which he also played the lead. "Lose Yourself" would go on to become the longest running No. 1 hip hop single.[3] Eminem then went on hiatus after touring in 2005. -

Movie Discussion Resource.Vice

Movie discussion resource Vice (2018) Engage with culture without disengaging your faith. Genre: Drama/biopic Rating: MA15+ (for some violent images) Length: 132 minutes Starring: Christian Bale, Amy Adams,Steve Carell, Sam Rockwell Writer/Director: Adam McKay Synopsis “Vice” covers 50 years in the life of Dick Cheney (Christian Bale), beginning in his early years as a Wyoming-based electrical worker, Yale dropout, and drunken disappointment to his strong-willed and influential wife Lynne (Amy Adams). Advised to either clean up his act or lose his family, Cheney eventually finds his footing in politics, starting off as a Congressional intern in the Nixon Administration, where he is mentored by Donald Rumsfeld (Steve Carell) and gains an intimate understanding of the power system and how to thrive within it. After a successful political career that included earning the roles of White House Chief of Staff under Gerald Ford, 5 terms in Congress, and Secretary of Defence to George H.W. Bush, Cheney puts politics in his rearview to focus on his family and gain wealth in the role of CEO at oil behemoth Halliburton. At this point Cheney could have settled happily into retirement. When George H.W. Bush’s “black sheep” son, George W. (Sam Rockwell), decides to run for presi- dent in 2000, he asks Cheney to be his VP. Cheney sees an opportunity to transform the sym- bolic position into the most powerful role in the Oval Office. When Bush unexpectedly beats Al Gore in the 2000 election, Cheney is given carte blanche in selecting the transition team, which he populates with PNAC (see explanation below) loyalists. -

Processing Natural Language for the Spotify API Are Sophisticated Natural Language Processing Algorithms Necessary When Processing Language in a Limited Scope?

EXAMENSARBETE INOM TEKNIK, GRUNDNIVÅ, 15 HP STOCKHOLM, SVERIGE 2016 Processing Natural Language for the Spotify API Are sophisticated natural language processing algorithms necessary when processing language in a limited scope? PATRIK KARLSTRÖM ARON STRANDBERG KTH SKOLAN FÖR DATAVETENSKAP OCH KOMMUNIKATION Processing Natural Language for the Spotify API Bearbetning av Naturligt Spr˚aktill Spotifys API Authors Patrik Karlstr¨om Aron Strandberg Group 75 Supervisor Michael Minock Examiner Orjan¨ Ekeberg 2016-05-11 1 English Abstract Knowing whether you can implement something complex in a simple way in your application is always of interest. A natural language interface is some- thing that could theoretically be implemented in a lot of applications but the complexity of most natural language processing algorithms is a limiting factor. The problem explored in this paper is whether a simpler algorithm that doesn’t make use of convoluted statistical models and machine learning can be good enough. We implemented two algorithms, one utilizing Spotify’s own search and one with a more accurate, o✏ine search. With the best precision we could muster being 81% at an average of 2,28 seconds per query this is not a viable solution for a complete and satisfactory user experience. Further work could push the performance into an acceptable range. 2 Swedish Abstract Att kunna implementera till synes komplexa funktioner till sitt program p˚a ett simpelt s¨att ¨aralltid av intresse. Ett gr¨anssnitt f¨ornaturligt spr˚ak¨arn˚agot som teoretiskt s¨att g˚aratt implementera i m˚anga applikationer men komplex- iteten i de flesta bearbetningalgoritmerna f¨ornaturligt spr˚ak¨aren begr¨ansande faktor. -

“Virtual Cloning” Shannon Flynn Smith

3 3 9 v irtual Cloning: tr anSfor M ation or iMitation? Reforming the Saderup Court’s transformative Use test for Rights of Publicity S H a nnon f ly n n S m i t H * Introduction upac Shakur, dead nearly sixteen years, rose up slowly from beneath T the stage at the 2012 Coachella Valley Music & Arts Festival in Indio, California to rouse the crowd and perform his songs 2 of Amerikaz Most Wanted and Hail Mary alongside rap artists Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre.1 Ce- line Dion and Elvis Presley belted If I Can Dream together in a duet on the hit performance show American Idol in 2007,2 thirty years after Presley’s This paper was awarded third place in the California Supreme Court Historical Society’s 2014 CSCHS Selma Moidel Smith Law Student Writing Competition in California Legal History. * J.D., 2014, Michigan State University College of Law; B.A. (Journalism), 2011, Uni- versity of Wyoming. She is now a member of the Colorado State Bar. The author would like to thank Adam Candeub for his thoughtful assistance in developing this article. 1 Claire Suddath, How Tupac Became a Hologram (Is Elvis Next?), Businessweek (Apr. 16, 2012), http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2012-04-16/how-tupac-became-a- hologram-plus-is-elvis-next; Tupac Hologram Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre Perform Coachella Live 2012, YouTube (Apr. 17, 2012), http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TGbrFmPBV0Y [hereinafter Tupac Live Hologram]. 2 American Idol Elvis & Celine Dion “If I Can Dream,” YouTube (Jan. 8, 2010), http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p1HtPG6eMIo. -

2009 Inaugural Media Guide

The 56th Presidential Inauguration Inaugural media guide Produced by the joint congressional committee on inaugural ceremonies January 2009 Table of Contents About the Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies (JCCIC) JCCIC Members Media Timeline 2009 Inaugural Ceremonies Processions to the Platform Inaugural Program Musical Selections Bios Aretha Franklin Yo-Yo Ma Anthony McGill Gabriela Montero Itzhak Perlman John Williams Elizabeth Alexander Pastor Rick Warren The Reverend Dr. Joseph E. Lowery San Francisco Boys Chorus (SFBC) San Francisco Girls Chorus (SFGC) The United States Army Herald Trumpets The United States Marine Band The United States Navy Band "Sea Chanters‖ Lincoln Bible President’s Room Inaugural Luncheon Program Menu Recipes Painting Inaugural Gifts Smithsonian Chamber Players History of Statuary Hall Event Site Map Images of Tickets Biographies President George W. Bush President – elect Barack Obama Vice President Dick Cheney Vice President - elect Joe Biden Mrs. Laura Bush Mrs. Michelle Obama Mrs. Lynne Cheney Dr. Jill Biden Justices of the Supreme Court U.S. Capitol History and Facts Inaugural History Morning Worship Service Procession to the Capitol Vice President’s Swearing–In Ceremony Presidential Swearing-In Ceremony Inaugural Address Inaugural Luncheon Inaugural Parade Inaugural Ball Inaugural Facts and Firsts AFIC (armed forces inaugural committee) AFIC History & Fact Sheet Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies (JCCIC) Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies (JCCIC) The Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies (JCCIC) plans and executes all Inaugural activities at the United States Capitol, including the Inaugural swearing-in ceremony of the President and Vice President of the United States and the traditional Inaugural luncheon that follows. -

Federal Bureau of Investigation

O O FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION FREEDOM OF INFORMATION AND PRIVACY ACTS SUBJECT: TUPAC SHAKUR FEDERALOF BUREAU INVESTICQION FOIPA DELETED PAGE INFORMATION SHEET Serial Description " COVER SHEET O1/03/1997 Total Deleted Page s! " 28 ~ Page Duplicate -| Page Duplicate ~ Page Duplicate ~ Page Duplicate ~ Page Duplicate ~ Page Duplicate ~ Page Duplicate ~ Page Duplicate ~ Page Duplicate ~ Page Duplicate ~ Page Duplicate ~ Page Duplicate ~ Page Duplicate ~ Page Duplicate ~ Page Duplicate ~ Page Duplicate -I Page Duplicate ~ Page Duplicate -: Page Duplicate ~ Page Duplicate 4-: Page Duplicate ~ Page b7C ~ Page b7C FREEDOM OF INFORMATION AND PRIVACY ACTS SUBJECTT O Tupap _S11:;kyr___ ii I _ FILE NUMBER __ 266A-OLA-2Q1_8Q74 VI-IQ!_ _ _ _ _ _ SECTION NUMBER: _ ,7 _1_ _ _ _ FEDERAL BUREAUOF INVESTIGATION 2/3:/1995! FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION Precedence: ROUTINE Date: 01/03/1997 4/{oz FBIHeadquarters Attn: NSD, CTBranch, DTS,DTOU From! Los Angeles NSD~6 ApprovedI By:I Drafted By: mpbh}I92'I'I'M' Case ID #= 266A-LA-2o1so7,¬3 - ECEASED!;I _ ERIC WRIGHT,AKA EAZY~EVICTIM DECEASED!; WC AOTDTDEATH THREATS 00; LOS ANGELES ARMED AND DANGEROUS synopsis: Status of investigation and request for extension to PI. Previous Title: | _| ET AL; TUPAC SHAKURVICTIM DECEASED!; EAZY-EVICTIM DECEASED!; ACT-DT-DEATH THREATS; O02 LOS ANGELE$ Preliminary Inquiry Initiated: 10/1'7/1996, set to expire 01/17/1995. Enclosures: One original and five copies of a Letterhead Memorandum, dated 01/O3/1997. Details: Title marked changed to reflect the true name of EAZY-E. Enclosed for the Bureau are one original and five copies of a Letterhead Memorandum, dated O1/03/1997, which contains the current status of captioned matter. -

What's Included

WHAT’S INCLUDED ENCORE (EMINEM) » Curtains Up » Just Lose It » Evil Deeds » Ass Like That » Never Enough » Spend Some Time » Yellow Brick Road » Mockingbird » Like Toy Soldiers » Crazy in Love » Mosh » One Shot 2 Shot » Puke » Final Thought [Skit] » My 1st Single » Encore » Paul [Skit] » We as Americans » Rain Man » Love You More » Big Weenie » Ricky Ticky Toc » Em Calls Paul [Skit] CURTAIN CALL (EMINEM) » Fack » Sing For The Moment » Shake That » Without Me » When I’m Gone » Like Toy Soldiers » Intro (Curtain Call) » The Real Slim Shady » The Way I Am » Mockingbird » My name Is » Guilty Conscience » Stan » Cleanin Out My Closet » Lose Yourself » Just Lose It » Shake That RELAPSE (EMINEM) » Dr. West [Skit] » Stay Wide Awake » 3 A.M. » Old Time’s Sake » My Mom » Must Be the Ganja » Insane » Mr. Mathers [Skit] » Bagpipes from Baghdad » Déjà Vu » Hello » Beautiful » Tonya [Skit] » Crack a Bottle » Same Song & Dance » Steve Berman [Skit] » We Made You » Underground » Medicine Ball » Careful What You Wish For » Paul [Skit] » My Darling Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. All rights reserved. Page. 1 WHAT’S INCLUDED RELAPSE: REFILL (EMINEM) » Forever » Hell Breaks Loose » Buffalo Bill » Elevator » Taking My Ball » Music Box » Drop the Bomb On ‘Em RECOVERY (EMINEM) » Cold Wind Blows » Space Bound » Talkin’ 2 Myself » Cinderella Man » On Fire » 25 to Life » Won’t Back Down » So Bad » W.T.P. » Almost Famous » Going Through Changes » Love the Way You Lie » Not Afraid » You’re Never Over » Seduction » [Untitled Hidden Track] » No Love THE MARSHALL MATHERS LP 2 (EMINEM) » Bad Guy » Rap God » Parking Lot (Skit) » Brainless » Rhyme Or Reason » Stronger Than I Was » So Much Better » The Monster » Survival » So Far » Legacy » Love Game » Asshole » Headlights » Berzerk » Evil Twin Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. -

Album Top 1000 2021

2021 2020 ARTIEST ALBUM JAAR ? 9 Arc%c Monkeys Whatever People Say I Am, That's What I'm Not 2006 ? 12 Editors An end has a start 2007 ? 5 Metallica Metallica (The Black Album) 1991 ? 4 Muse Origin of Symmetry 2001 ? 2 Nirvana Nevermind 1992 ? 7 Oasis (What's the Story) Morning Glory? 1995 ? 1 Pearl Jam Ten 1992 ? 6 Queens Of The Stone Age Songs for the Deaf 2002 ? 3 Radiohead OK Computer 1997 ? 8 Rage Against The Machine Rage Against The Machine 1993 11 10 Green Day Dookie 1995 12 17 R.E.M. Automa%c for the People 1992 13 13 Linkin' Park Hybrid Theory 2001 14 19 Pink floyd Dark side of the moon 1973 15 11 System of a Down Toxicity 2001 16 15 Red Hot Chili Peppers Californica%on 2000 17 18 Smashing Pumpkins Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness 1995 18 28 U2 The Joshua Tree 1987 19 23 Rammstein Muaer 2001 20 22 Live Throwing Copper 1995 21 27 The Black Keys El Camino 2012 22 25 Soundgarden Superunknown 1994 23 26 Guns N' Roses Appe%te for Destruc%on 1989 24 20 Muse Black Holes and Revela%ons 2006 25 46 Alanis Morisseae Jagged Liale Pill 1996 26 21 Metallica Master of Puppets 1986 27 34 The Killers Hot Fuss 2004 28 16 Foo Fighters The Colour and the Shape 1997 29 14 Alice in Chains Dirt 1992 30 42 Arc%c Monkeys AM 2014 31 29 Tool Aenima 1996 32 32 Nirvana MTV Unplugged in New York 1994 33 31 Johan Pergola 2001 34 37 Joy Division Unknown Pleasures 1979 35 36 Green Day American idiot 2005 36 58 Arcade Fire Funeral 2005 37 43 Jeff Buckley Grace 1994 38 41 Eddie Vedder Into the Wild 2007 39 54 Audioslave Audioslave 2002 40 35 The Beatles Sgt.