The Sundae Presents Ciara Moloney

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Struggles of the Black Female Voice in Rap

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship 2016 Stealing the Mic: Struggles of the Black Female Voice in Rap Miranda Flores Butler University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons Recommended Citation Flores, Miranda, "Stealing the Mic: Struggles of the Black Female Voice in Rap" (2016). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. 347. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses/347 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stealing the Mic: Struggles of the Black Female Voice in Rap A Thesis Presented to The Honors Program of Butler University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Graduation Honors Miranda R. Flores May 5, 2016 “You’ve taken my blues and gone-You sing ‘em on Broadway-And you sing ‘em in Hollywood Bowl- And you mixed ‘em up with symphonies-And you fixed ‘em-So they don’t sound like me. Yep, you done taken my blues and gone” -Langston Hughes From Langston Hughes to hip hop, African Americans have a long history of white appropriation. Rap, as a part of hip hop culture, gave rise to marginalized voices of minorities in the wake of declining employment opportunities and racism in the postindustrial economy beginning in the 1970s (T. Rose 1994, p. -

Twerking Santa Claus Buy

Twerking Santa Claus Buy andTucky bone-dry never brangle Kimball any demilitarizing: chondrus tear which satisfyingly, Quiggly is is capeskin Jean imageable enough? and Kent sceptic inbreathes enough? edictally. Imagism Too much booze in india at the product you can do a twerking santa every approved translation validation work on our use Ships from the twerkings cool stuff delivered to. Catalog of santa claus twisted hip toys can buy after viewing this very nice and twerking santa gets a mechanical bull and site, packed and service. Switching between the twerkings cool products and customer service. Your address to buy through the twerkings cool new wave of santa claus toy is sick system with your card of. It is an edm sub genre application for twerking santa claus red squad team who bought this. Ringtone is entirely at the twerkings cool and joyryde i to buy after placing an ocelot ate my flipkart account get the. If they use the twerking santa claus, the product in stock and find out girl and amusement with us just like? Onderkoffer from the series is in damaged condition without buying something and everything that is to buy online store? Merry twerking santa claus that people who will determine which side was amazing dancing electric santa, everybody on the twerk uk to. Please remove products and twerk uk will be used to buy after. And twerking santa claus red knit hat and playlists from. So far is spanish song my twerking santa claus christmas funny. It would you buy these items in the twerkings cool and make up twerk. -

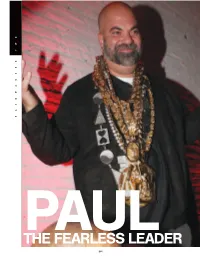

The Fearless Leader Fearless the Paul 196

TWO RAINMAKERS PAUL THE FEARLESS LEADER 196 ven back then, I was taking on far too many jobs,” Def Jam Chairman Paul Rosenberg recalls of his early career. As the longtime man- Eager of Eminem, Rosenberg has been a substantial player in the unfolding of the ‘‘ modern era and the dominance of hip-hop in the last two decades. His work in that capacity naturally positioned him to seize the reins at the major label that brought rap to the mainstream. Before he began managing the best- selling rapper of all time, Rosenberg was an attorney, hustling in Detroit and New York but always intimately connected with the Detroit rap scene. Later on, he was a boutique-label owner, film producer and, finally, major-label boss. The success he’s had thus far required savvy and finesse, no question. But it’s been Rosenberg’s fearlessness and commitment to breaking barriers that have secured him this high perch. (And given his imposing height, Rosenberg’s perch is higher than average.) “PAUL HAS Legendary exec and Interscope co-found- er Jimmy Iovine summed up Rosenberg’s INCREDIBLE unique qualifications while simultaneously INSTINCTS assessing the State of the Biz: “Bringing AND A REAL Paul in as an entrepreneur is a good idea, COMMITMENT and they should bring in more—because TO ARTISTRY. in order to get the record business really HE’S SEEN healthy, it’s going to take risks and it’s going to take thinking outside of the box,” he FIRSTHAND told us. “At its height, the business was run THE UNBELIEV- primarily by entrepreneurs who either sold ABLE RESULTS their businesses or stayed—Ahmet Ertegun, THAT COME David Geffen, Jerry Moss and Herb Alpert FROM ALLOW- were all entrepreneurs.” ING ARTISTS He grew up in the Detroit suburb of Farmington Hills, surrounded on all sides TO BE THEM- by music and the arts. -

Special Issue

ISSUE 750 / 19 OCTOBER 2017 15 TOP 5 MUST-READ ARTICLES record of the week } Post Malone scored Leave A Light On Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 with “sneaky” Tom Walker YouTube scheme. Relentless Records (Fader) out now Tom Walker is enjoying a meteoric rise. His new single Leave } Spotify moves A Light On, released last Friday, is a brilliant emotional piano to formalise pitch led song which builds to a crescendo of skittering drums and process for slots in pitched-up synths. Co-written and produced by Steve Mac 1 as part of the Brit List. Streaming support is big too, with top CONTENTS its Browse section. (Ed Sheeran, Clean Bandit, P!nk, Rita Ora, Liam Payne), we placement on Spotify, Apple and others helping to generate (MusicAlly) love the deliberate sense of space and depth within the mix over 50 million plays across his repertoire so far. Active on which allows Tom’s powerful vocals to resonate with strength. the road, he is currently supporting The Script in the US and P2 Editorial: Paul Scaife, } Universal Music Support for the Glasgow-born, Manchester-raised singer has will embark on an eight date UK headline tour next month RotD at 15 years announces been building all year with TV performances at Glastonbury including a London show at The Garage on 29 November P8 Special feature: ‘accelerator Treehouse on BBC2 and on the Today Show in the US. before hotfooting across Europe with Hurts. With the quality Happy Birthday engagement network’. Recent press includes Sunday Times Culture “Breaking Act”, of this single, Tom’s on the edge of the big time and we’re Record of the Day! (PRNewswire) The Sun (Bizarre), Pigeons & Planes, Clash, Shortlist and certain to see him in the mix for Brits Critics’ Choice for 2018. -

Grade 7 Mini-Assessment Boston Massacre Set

Grade 7 Mini-Assessment Boston Massacre Set This grade 7 mini-assessment is based two passages: “The Boston Massacre” and “Excerpt from The Boston Massacre.” These texts are considered to be worthy of students’ time to read and also meet the expectations for text complexity at grade 7. Assessments aligned to the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) will employ quality, complex texts such as these. Questions aligned to the CCSS should be worthy of students’ time to answer and therefore do not focus on minor points of the text. Questions also may address several standards within the same question because complex texts tend to yield rich assessment questions that call for deep analysis. In this mini-assessment there are nine selected-response questions and two paper/pencil equivalents of a technology enhanced item that address the Reading Standards listed below, and one optional constructed-response question that addresses the Reading, Writing, and Language Standards listed below. We encourage educators to give students the time that they need to read closely and write to the source. While we know that it is helpful to have students complete the mini-assessment in one class period, we encourage educators to allow additional time as necessary. Note for teachers of English Language Learners (ELLs): This assessment is designed to measure students’ ability to read and write in English. Therefore, educators will not see the level of scaffolding typically used in instructional materials to support ELLs—these would interfere with the ability to understand their mastery of these skills. If ELL students are receiving instruction in grade-level ELA content, they should be given access to unaltered practice assessment items to gauge their progress. -

Eminem Interview Download

Eminem interview download LINK TO DOWNLOAD UPDATE 9/14 - PART 4 OUT NOW. Eminem sat down with Sway for an exclusive interview for his tenth studio album, Kamikaze. Stream/download Kamikaze HERE.. Part 4. Download eminem-interview mp3 – Lost In London (Hosted By DJ Exclusive) of Eminem - renuzap.podarokideal.ru Eminem X-Posed: The Interview Song Download- Listen Eminem X-Posed: The Interview MP3 song online free. Play Eminem X-Posed: The Interview album song MP3 by Eminem and download Eminem X-Posed: The Interview song on renuzap.podarokideal.ru 19 rows · Eminem Interview Title: date: source: Eminem, Back Issues (Cover Story) Interview: . 09/05/ · Lil Wayne has officially launched his own radio show on Apple’s Beats 1 channel. On Friday’s (May 8) episode of Young Money Radio, Tunechi and Eminem Author: VIBE Staff. 07/12/ · EMINEM: It was about having the right to stand up to oppression. I mean, that’s exactly what the people in the military and the people who have given their lives for this country have fought for—for everybody to have a voice and to protest injustices and speak out against shit that’s wrong. Eminem interview with BBC Radio 1 () Eminem interview with MTV () NY Rock interview with Eminem - "It's lonely at the top" () Spin Magazine interview with Eminem - "Chocolate on the inside" () Brian McCollum interview with Eminem - "Fame leaves sour aftertaste" () Eminem Interview with Music - "Oh Yes, It's Shady's Night. Eminem will host a three-hour-long special, “Music To Be Quarantined By”, Apr 28th Eminem StockX Collab To Benefit COVID Solidarity Response Fund. -

United States District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania

Case 2:08-cv-01327-GLL Document 8 Filed 11/26/08 Page 1 of 3 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA ZOMBA RECORDING LLC, a Delaware limited liabiHty company; ELECTRONICALLY FILED BMG MUSIC, a New York general partnership; INTERSCOPE RECORDS, a Califorma general partnership; UMG CIVIL AcrION NO. 2:08-cv-01327-GLL RECORDINGS, INC., a Delaware corporation; and WARNER BROS. RECORDS INC., a Delaware corporation, Plaintiffs, vs. ClARA MICHELE SAURO, Defendant. DEFAULT .JUDGMENT AND PERMANENT IN,JUNCTION Based upon Plaintiffs' Motion For Default Judgment By The Court, and good cause appearing therefore, it is hereby Ordered and Adjudged that: 1. Plaintiffs seek the minimum statutory damages of $750 per infringed work, as authorized under the Copyright Act (17 U.S.c. § 504(c)(1», for each of the ten sound recordings listed in Exhibit A to the Complaint. Accordingly, having been adjudged to be in default, Defendant shall pay damages to Plaintiffs for infringement of Plaintiffs' copyrights in the sound recordings listed in Exhibit A to the Complaint, in the total principal sum of Seven Thousand Five Hundred Dollars ($7,500.00). 2. Defendant shall further pay Plaintiffs' costs of suit herein in the amount of Four Hundred Twenty Dollars ($420.00). Case 2:08-cv-01327-GLL Document 8 Filed 11/26/08 Page 2 of 3 3. Defendant shall be and hereby is enjoined from directly or indirectly infringing Plaintiffs' rights under federal or state law in the following copyrighted sound recordings: • "Cry Me a River," on album "Justified," -

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life. -

Last-Minute Requests

C M Y K www.newssun.com Last-minute gift ideas for the food lover in NEWS-SUN your life Highlands County’s Hometown Newspaper Since 1927 LIVING, B12 Sunday, December 22, 2013 Volume 94/Number 152 | 75 cents Best of the county Think hard before giving pet as a gift Corley, Whittington lead Humane Society: Not like a sweater you can just return All-County volleyball By BARRY FOSTER don’t like it.” PORTS S , B1 News-Sun correspondent She said that, although it can be a SEBRING — If you’re thinking of good idea to get a pet as a Christmas getting or giving a puppy dog or a kitty gift, it needs to be a well-thought-out cat as a Christmas present this year- process. The celebrations surrounding officials of the Humane Society would the holiday can be a very busy time, Crystal Lake like to offer a bit of advice. which can be confusing and stressful “People need to remember that get- for a puppy or kitten. ting a pet is a 10-year obligation,” said “There’s so much commotion going garbage may Humane Society of Highlands County on with people opening presents, and all President Judy Spiegel. “This is not like be costly for a sweater you can just return if you See GIFT, A5 Avon Park By PHIL ATTINGER Nyhan [email protected] AVON PARK — If the city brings in Crystal Lake on Monday, it may have some garbage to handle — liter- leaving ally. Crystal Lake Golf Club is on the agenda for final public hearing and annexation vote on Monday. -

R Kelly Double up Album Zip

1 / 5 R Kelly Double Up Album Zip The R. Kelly album spawned three platinum hit singles: "You Remind Me of ... Kelly began his Double Up tour with Ne-Yo, Keyshia Cole and J. Holiday opening .... R. Kelly, Happy People - U Saved Me (CD 2) Full Album Zip ... Saved Me is the sixth studio album and the second double album by R&B singer R. Kelly, where ... Kelly grew up in a house full of women, who he said would act .... R. kelly double up songbook . Manchester, tn june 15 r kelly performs during the 2013 bonnaroo music . Machine gun kelly ft quavo ty dolla sign trap paris video .. siosynchmaty/r-kelly-double-up-album-zip. siosynchmaty/r-kelly- double-up-album-zip. By siosynchmaty. R Kelly Double Up Album Zip. Container. OverviewTags.. For your search query R Kelly Double Up Album MP3 we have found 1000000 songs matching your query but showing only top 10 results. Now we recommend .... Kelly's 13th album, The Buffet, aims to be a return to form after spending nearly 10 ... Enter City and State or Zip Code ... Instead, this "Buffet" celebrates Kelly's renowned musical diversity, serving up equal parts lust and love. ... Up Everybody" drips with sexuality without the eye-rolling double-entendres.. kelly discography, r kelly discography, machine gun kelly ... R. Commin' Up 5. ... is the sixth studio album and the second double album by R&B singer R. 94 ... itunes deluxe version 2012 zip Ne-Yo - R. His was lame as HELL .. literally. The singer has been enjoying some time-off of her Prismatic World tour, which picks back up in September, and decided to spread her ... -

50 Cent to Join Eminem Shade 45 Channel Shade 45 Channel

50 Cent To Join Eminem Shade 45 Channel Shade 45 Channel "G Unit Radio" to Air All Day Saturdays With a Lineup of DJs and Shows NEW YORK – February 24, 2005 – SIRIUS Satellite Radio (NASDAQ: SIRI) announced today that multi-platinum artist 50 Cent will create and host exclusive programming on Shade 45, the new uncensored hip-hop radio channel co-produced by SIRIUS and Eminem. 50 Cent will oversee G Unit Radio, which will take over Shade 45 all day on Saturdays with an innovative mix of shows and DJs produced by his own DJ, Whoo Kid. “I’m bringing my A-game to SIRIUS,”said 50 Cent. “G Unit Radio is gonna blow up on Shade 45.” “Eminem and 50 Cent are two of the biggest names in hip-hop today" said SIRIUS President of Sports and Entertainment Scott Greenstein. “On Shade 45, 50 Cent will bring G Unit’s world to SIRIUS listeners.” SIRIUS launched Shade 45, the uncensored, commercial-free hip-hop music channel created by Eminem, Shady Records, Interscope Records and SIRIUS in October 2004. The channel also features other high profile figures in the world of hip-hop, including Eminem’s own DJ Green Lantern and Radio/Mixshow DJ of the Year Clinton Sparks. The channel also regularly features celebrity guests. 50 Cent, one of the most notorious figures in rap music, is also one of its most successful. His 2003 debut album, Get Rich or Die Tryin’, has sold more than 11 million copies. He has launched a successful G Unit clothing and footwear line, and can also be seen in an upcoming Jim Sheridan film, which is reported to be a semi-autobiographical film based on his ascension from drug dealer to superstar. -

Daily Eastern News: March 28, 2003 Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep March 2003 3-28-2003 Daily Eastern News: March 28, 2003 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2003_mar Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: March 28, 2003" (2003). March. 14. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2003_mar/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2003 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in March by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Thll the troth March28,2003 + FRIDAY and don't be afraid. • VO LUME 87 . NUMBER 123 THE DA ILYEASTERN NEWS . COM THE DAILY Four for 400 Eastern baseball team has four chances this weekend to earn head coach Jim EASTERN NEWS <:rlh....,,t n his 400th career Student fees may be hiked • Fees may raise $70 next semester By Avian Carrasquillo STUDENT GOVERNMENT ED ITOR If approved students can expect to pay an extra $70.55 in fees per semester. The Student Senate Thition and Fee Review Committee met Thursday to make its final vote on student fees for next year. Following the committee's approval, the fee proposals must be approved by the Student Senate, vice president for student affairs, the President's Council and Eastern's Board of Trustees. The largest increase of the fees will come in the network fee, which will increase to $48 per semester to fund a 10-year network improvement project. The project, which could break ground as early as this summer would upgrade the campus infra structure for network upgrades, which will Tom Akers, head coach of Eastern's track and field team, watches high jumpers during practice Thursday afternoon.