Blank Slate: Squares and Political Order of City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manifestation of Modernity in Iranian Public Squares: Baharestan Square (1826–1978)

Asma Mehan, Int. J. of Herit. Archit., Vol. 1, No. 3 (2017) 411–420 MANIFESTATION OF MODERNITY IN IRANIAN PUBLIC SQUARES: BAHARESTAN SQUARE (1826–1978) ASMA MEHAN Department of Architecture and Design, Politecnico Di Torino, Italy. ABSTRACT The concept of public square has changed significantly in Iran in recent centuries. This research inves- tigated how modernity is manifested in the public squares of Tehran. In this regard, Tehran has been chosen as the main concern, while in its short history as the capital of Iran, the city has been critically transformed: first because of constant urban development during the Qajar Dynasty and then due to its rapid growth during the late Pahavi era and second because of the culture of rapid renovation and reconstruction in contemporary public spaces. Considering these facts, the urban transformation of Baharestan Square as one of the most influencing public squares of Tehran in the recent century leads us to understand the process of Iranian modernization, which is totally different from common patterns of western modernity. Analysing the historical changes of Baharestan Square based on manuscripts, western travellers’ diaries, historical images and maps, from its formation till the Islamic Revolution (1978), shows how the traditional elements of the square as well as its form and function have been totally transformed. Analysing the spatial qualities of Baharestan Square clarifies that its special loca- tion near the first Iranian Parliament building, Sepahsalar Mosque and Negarestan Garden represents it as the first modern focal point in Iranian’s political and social life. Keywords: Baharestan Square, Iranian modernity, public square, Tehran. -

Sample File P’ A Karachi S T Demavend J Oun to M R Doshan Tappan Muscatto Kand Airport

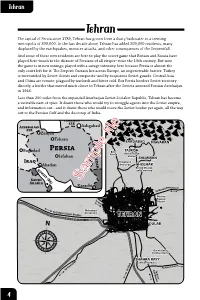

Tehran Tehran Tehran The capital of Persia since 1789, Tehran has grown from a dusty backwater to a teeming metropolis of 800,000. In the last decade alone, Tehran has added 300,000 residents, many displaced by the earthquakes, monster attacks, and other consequences of the Serpentfall. And some of these new residents are here to play the secret game that Britain and Russia have played here–much to the distaste of Persians of all stripes–since the 19th century. But now the game is in new innings; played with a savage intensity here because Persia is almost the only court left for it. The Serpent Curtain lies across Europe, an impenetrable barrier. Turkey is surrounded by Soviet clients and conquests–and by suspicious Soviet guards. Central Asia and China are remote, plagued by warlords and bitter cold. But Persia borders Soviet territory directly, a border that moved much closer to Tehran after the Soviets annexed Persian Azerbaijan in 1946. Less than 200 miles from the expanded Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic, Tehran has become Tbilisia veritable nest of spies. It draws those who would try to smuggle agents into the Soviet empire, and information out…and it draws those who would move the Soviet border yet again, all the way out to the PersianBaku Gulf and the doorstep of India.Tashkent T Stalinabad SSR A Ashgabad SSR Zanjan Tehran A S KabulSAADABAD NIAVARAN Damascus Baghdad P Evin TAJRISH Prison Red Air Force Isfahan Station SHEMIRAN I Telephone Jerusalem Abadan Exchange GHOLHAK British Mission and Cemetery R S Sample file P’ A Karachi S t Demavend J oun To M R Doshan Tappan MuscatTo Kand Airport Mehrabad Jiddah To Zanjan (Soviet Border) Aerodrome BombayTEHRAN N O DULAB Gondar A A Aden S Qul’eh Gabri Parthian Ruins SHAHRA RAYY Medieval Ruins To Garm Sar Salt Desert To Hamadan To Qom To Kavir 4 Tehran Tehran THE CHARACTER OF TEHRAN Tehran sits–and increasingly, sprawls–on the southern slopes of the Elburz Mountains, specifically Mount Demavend, an extinct volcano that towers 18,000 feet above sea level. -

8 Day S &7 Nights

8 DAY S &7 NIGHTS Itinerary Code : 8D-94-US1 TEHRAN – SHIRAZ– ISFAHAN – ABYANEH – Date of issue: 17 AUG 2015 KASHAN Valid till March 4th 2016 Itinerary Note: “B” Breakfast / “L” Lunch / “D” Dinner / “A” Airplane /“T“Train/ “-” Not included Day 1 Arrival in Tehran at 22:20 meet and greet the Tehran tour guide. Check into the hotel then rest. B/-/-/A/- Day 2 Visit Tehran including: GolestanPalace Tehran (including two palaces), Jewellery Museum, B/L/D/-/- National Museum of Iran, Glassware Museum, Bagh-e Melli, Toopkhaneh Square, Grand Bazaar of Tehran. Return to hotel then rest. Day 3 Flight to Shiraz in early morning. Arrive to Tehran-Shiraz Shiraz. Visit Shiraz including: Arg of Karim B/L/D/A/- Khan, Qavam House, Eram Garden, Tomb of (924Km) Hafez, Tomb of Saadi, ZinatolMolk House, SarayeMoshir,Vakil Bazaar, Vakil Bath, Nasir olMolk Mosque. Day 4 Visit Persepolis, Naqsh-e Rajab, Naqsh-e Shiraz Rostam, Cube of Zoroaster, Afif Abad B/L/D/-/- Garden Day 5 Transfer to Isfahan. Visit Pasargad and The Shiraz- Isfahan Cypress of Abarkuh on the way. In the B/L/D/-/- afternoon, visit Isfahan famous bridges (425Km) (Khajoo&Siose Pol) No 495, Near Salehi Alley, Niavaran Ave. Tehran. Iran Website : www.ariantourist.com Tel : (+98 21) 22724121 Email : [email protected] Fax : (+98 21) 22744969 : www.facebook.com/ariantourist1 8 DAY S &7 NIGHTS Itinerary Code : 8D-94-US1 TEHRAN – SHIRAZ– ISFAHAN – ABYANEH – Date of issue: 17 AUG 2015 KASHAN Valid till March 4th 2016 Day 6 Visit Naqsh-e-Jahan Square, Ali Qapu, Imam Isfahan Mosque, Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque, B/L/D/-/- HashtBehesht, ChehelSotoun and Bazaar Day 7 Transfer to Tehran. -

War and Urban Sculptures of Tehran from an Objective Reality to a Subjective Matter*

Special Issue | War-Scape War and Urban Sculptures of Tehran From an Objective Reality to a Subjective Matter* Padideh Adelvand Abstract | The numerous wars such as the war against Russia in Qajar era, Ph.D. Candidate in Art Research, Alzahra University, the World War II in Pahlavi era and the 8-year war against Iraq in the Islamic Nazar research center, Tehran, Republic of Iran are experiences that the contemporary Iran has tasted its Iran. flavor. On the other hand, the experience of existing urban sculpture in [email protected] contemporary Tehran brings this question to mind that how the urban sculpture as a form of art, could reflect the war experience? And what approaches has been emerged in artworks over the representation of the war issue in different periods? This article is based on a documentary research that, the statues have been discussed as a document. According to the historical documents and books, a total of 47 dated sculptures related to the war issue from the Qajar era up to 1389SH. were studied. The results of this study showed that Tehran's sculptures can be divided into two main sections, "Qajar to the Islamic Revolution" and "Islamic Revolution to 2010". In the first section due to the much experiences and significant raids into the country, war is comprehended as the general definition means "aggression". Therefore, the government policy through the urban sculptures located in the squares - as a state element- is trying to project the military power; from the cannons, as the first examples, to the cavalry bodies of King. -

Iranians' Positive Criticism on European Architecture and Its

Bagh-e Nazar, 17(83), 5-16 /May. 2020 DOI: 10.22034/bagh.2019.188582.4146 Persian translation of this paper entitled: تمجیدهای ایرانیان از معماری فرنگ و رابطۀ آن با انتقادهای آنان از معماری ایران در اواخر دوران قاجار is also published in this issue of journal. Iranians’ Positive Criticism on European Architecture and Its Correlation with Their Negative Criticism on Iranian Architecture and Town Planning during the Late Qajar Era Saeed Haghir*1, Kamyar Salavati2 1. Associate Professor, Faculty of Architecture, University of Tehran, Iran. 2. M.A. in Iranian Architectural Studies, Faculty of Architecture, University of Tehran, Iran. Received: 02/06/2019 ; revised: 12/09/2019 ; accepted: 23/09/2019 ; available online: 20/04/2020 Abstract Problem statement: Several factors caused the fundamental changes of Iranian architecture during the early 20th century. One of these factors was the personal observations of the Iranian in Europe. These observations were effective from an urban and architectural point of view and they probably had effects on the architectural and urban mentalities of the Iranians. Research objective: The main aim of this paper is to review and categorize the positive criticism of Iranians on the European towns and architecture in the late Qajar era until Reza Pahlavi’s coup, then to compare them with the negative criticism of Iranians on architecture and town planning in Iran in the same period. Research Method: This paper applies a hermeneutic-historical method. It is formulated in the theoretical framework of the “Multiple Modernities” theory. In this research, 21 late Qajar travelogues have been reviewed and the data related to the research questions have been separated and categorized. -

Research Article

Journal of Fundamental and Applied Sciences Research Article ISSN 1112-9867 Available online at http://www.jfas.info THE STUDY OF THE EVOLUTION OF SQUARES IN 3 PERIODS OF SAFAVID, QAJAR AND PAHLAVI WITH HISTORICAL – EVOLUTIONARY AND FORM APPROACH (ISFAHAN AND TEHRAN STYLES) CASE STUDY OF NAQSHE JAHAN SQUARE IN ISFAHAN, GANJALIKHAN SQUARE IN KERMAN, SABZE MEYDAN AND TOOPKHANEH SQUARE A. Shafiee1 B. Faizi2 and C. Yazdanfar3* 1 Elham Shafiee, postgraduate student, Iran, University of Science and technology 2 Mohsen Faizi, professor of architecture and urbanism faculty, Iran, University of Science and technology 3 Seyed Abbas Yazdanfar, associate professor of architecture and urbanism faculty, Iran, University of Science and technology Published online: 05 June 2016 ABSTRACT Unfortunately, with the development of cities and arrival of modernism, the past function of spaces like urban squares has changed and lost its real concept. The arrival of modernism to Iran has influenced the spatial organization of Tehran since the late Qajar era. To clarify these changes, the present study aims to compare Isfahan style and Tehran style to show the evolution of squares from the Safavid to the first Pahlavi era. This study was performed in an interpretative- historical method and focused on squares in two styles of Isfahan and Tehran. In this study, Inductive and comparative approaches and the case studies of each style were used for interpretations and conclusions. Author Correspondence, e-mail: [email protected] doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/jfas.8vi2s.10 A. Shafiee et al. J Fundam Appl Sci. 2016, 8(2S), 138-162 139 The main features of each style after extraction were examined with the study of squares in that style. -

Travel to Tehran-Iran

Travel to Tehran-Iran ABOUT IRAN- HISTORY & HERITAGE The plateau of Iran is among the oldest civilization centers in the history of humanity and has an important place in archeological studies. The history of settlement in the Plateau of Iran, from the new Stone Age till the migration of Aryans to this region, is not yet very clear. But there is reliable evidence indicating that Iran has been inhabited since a very long time ago. Settlement centers have emerged close to water resources like springs, rivers, lakes or totally close to Alborz and Zagross mountains. After the decline of the Achievement dynasty, and the destruction of Persepolis by Alexander, his successors the Seleucid dominated over Iran for a short period of time. During this time the interaction between Iranian and Hellenic cultures occurred. Around the year 250 BC, the Parthians, who were an Aryan tribe as well as horse riders, advanced from Khorassan towards the west and south-west and founded their empire over Iran Plateau in Teesfoon. This empire survived only until the year 224 AD. The Sassanian, after defeating the last Parthia n king in 225 AD, founded a new empire which lasted until mid-7th century AD. With respect to its political, social, and cultural characteristics, the ancient period of Iran (Persia) is one of the most magnificent epochs of Iranian history. Out of this era, so many cultural and historical monuments have remained inPersepolis, Passargadae, Susa (Shoosh), Shooshtar, Hamadan, Marvdasht (Naqsh-e-Rostam), Taq-e- bostan, Sarvestan, and Nayshabur, which are worth seeing. The influence of Islam in Iran began in the early 7th century AD after the decline of the Sassanide Empire. -

A Democratic Alternative Education System for Iran: an Historical and Critical Study

A DEMOCRATIC ALTERNATIVE EDUCATION SYSTEM FOR IRAN: AN HISTORICAL AND CRITICAL STUDY by Mohammad Nasser Jahani Asl B.A. (Sociology and Anthropology), Simon Fraser University, 2003 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLlVIENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Faculty ofEducation © Mohammad Nasser Jahani Asl2007 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY 2007 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission ofthe author. APPROVAL Name: Mohammad Nasser Jahani Asl Degree: Master of Arts Title of Research Project: A Democratic Alternative Education System for Iran: An Historical and Critical Study Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Deborah Bartlette Geoff Madoc-Jones, Assistant Professor Senior Supervisor Michael Ling, Senior Lecturer Peyman Vabadzadeh Dr. Sean Blenkinsop, Assistant Professor External Examiner Date: July 18,2007 ii SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the "Institutional Repository" link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/1892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

The Urban Book Series Aims and Scope

The Urban Book Series Aims and Scope The Urban Book Series is a resource for urban studies and geography research worldwide. It provides a unique and innovative resource for the latest developments in the field, nurturing a comprehensive and encompassing publication venue for urban studies, urban geography, planning and regional development. The series publishes peer-reviewed volumes related to urbanization, sustainabil- ity, urban environments, sustainable urbanism, governance, globalization, urban and sustainable development, spatial and area studies, urban management, urban infrastructure, urban dynamics, green cities and urban landscapes. It also invites research which documents urbanization processes and urban dynamics on a national, regional and local level, welcoming case studies, as well as comparative and applied research. The series will appeal to urbanists, geographers, planners, engineers, architects, policy makers, and to all of those interested in a wide-ranging overview of contemporary urban studies and innovations in the field. It accepts monographs, edited volumes and textbooks. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/14773 Mahmoud Tavassoli Urban Structure in Hot Arid Environments Strategies for Sustainable Development 123 Mahmoud Tavassoli Urban Design University of Tehran Tehran Iran ISSN 2365-757X ISSN 2365-7588 (electronic) The Urban Book Series ISBN 978-3-319-39097-0 ISBN 978-3-319-39098-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-39098-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016939909 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. -

Memorialization of War Between Conflicts of Interest Before and After the Islamic Revolution: Public Art and Public Space in Iran Narciss Sohrabi Mollayousef

Memorialization of war between conflicts of interest before and after the Islamic Revolution: public art and public space in Iran Narciss Sohrabi Mollayousef To cite this version: Narciss Sohrabi Mollayousef. Memorialization of war between conflicts of interest before and after the Islamic Revolution: public art and public space in Iran. ARTis ON, Institute of Art History, School of Arts and Humanities, University of Lisbon, Portugal, 2018, 7 (Dezembro), pp.161-70. halshs- 02063067 HAL Id: halshs-02063067 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02063067 Submitted on 4 Mar 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. MEMORIALIZATION OF WAR BETWEEN CONFLICTS OF INTEREST BEFORE AND AFTER THE ISLAMIC REVOLUTION: PUBLIC ART AND PUBLIC SPACE IN IRAN Narciss M. Sohrabi Université Paris Ouest, Nanterre La Défense, Laboratoire LADYSS-UMR7355 [email protected] ABSTRACT Since 1800s, numerous wars have impacted the cities of Iran. Regarding the urban artwork in Tehran, the capital of Iran, the following question comes to mind: What approach has the urban artwork adopted to represent the war and its related concepts? Adopting a documentary research approach and investigating the concept of war in different eras, this paper attempts to study the sculptures in urban spaces as documents. -

Paisaje Sonoro E Identidad Cultural. Los Sonidos De Teherán En El Contexto De La Identidad Musical De Persia

Paisaje sonoro e identidad cultural. Los sonidos de Teherán en el contexto de la identidad musical de Persia Doctorado en Historia y Ciencias de la Música Departamento de la Música Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Autor Director Shahryar Zarrin Panjeh Jose Luis Carles Arribas Junio de 2017 1 Agradecimientos Me gustaría que estas líneas sirvieran para expresar mi más profundo y sincero agradecimiento a todas aquellas personas que con su ayuda han colaborado en la realización de esta tesis doctoral. En primer lugar, expreso un especial agradecimiento a Doctor Jose Luis Carles Arribas director de esta investigación, por la orientación, el seguimiento, colaboración, valiosos consejos y la supervisión continua de la misma, pero sobre todo por su gran generosidad y lucidez para formarme en el marco de la línea de la investigación. Quisiera hacer extensiva mi enorme gratitud a Doctora Cristina Palmese por su ayuda, generosa colaboración y valiosos consejos. También quiero dar las gracias a todos los profesores de la universidad Autónoma de Madrid destinados a mi formación y los estudios de doctorado, sobre todo un especial reconocimiento merece el interés mostrado por mi trabajo y las sugerencias recibidas por la Doctora Begoña Lolo. Quiero expresar también mi más sincero agradecimiento a todos los amigos que han participado en esta investigación. Sin ellos, no hubiera sido posible cristalizar este proyecto. Finalmente quiero agradecer a la persona más importante de mi vida, a mí esposa Atusa Hosseinzadeh, porque gracias a su amor, paciencia y apoyo, he tenido las fuerzas para sacar adelante esta tesis, y ha sido su constante comprensión, motivación y firmeza la que me ha permitido luchar día a día para alcanzar esta meta. -

Function of Iranian Cities in Safavid Erapolitical Cities Or Commercial Cities

Journal of Anthropology & Archaeology 1(1); June 2013 pp. 28-40 Taghavi, Farzin & Zoor Function of Iranian Cities in Safavid Erapolitical Cities or Commercial Cities Abed Taghavi Department of Archaeology University of Mazandaran Iran Saman Farzin Department of Archaeology University of Mazandaran Iran Maryam Zoor Student, Department of Archaeology University of Tarbiat Modares Iran Abstract History of City and Urbanization in Safavid dynasty is one of the most active as well as complicated social category. Distribution and function of each city in accordance with their political, economic, social and cultural role indicated their various functional changes. Besides the political origin of Iranian cities in this era, the economic relations that are depended on urban society, is one of the most important functions of the city as a social phenomenon. In Safavid Iran, this has played a decisive role in the activity of urban social life regarding to an organized definition of commodity, distribution and exchanging system between urban and rural society as well as defining the role of organization in commercial process.This paper is based on historical analyzing method, utilizing historical sources, and social and economic studies on urbanization defining Persian cities economic structure in Safavid era. Farah Abad, Isfahan and Bandar Abbas in north, center and south of Iran are examined to realize the developments which are logical and documentary. These are selected because of their functional nature which was producer, industrial (processor) and exporter cities. The result of this research shows that the founded and developed cities in Safavid Iran, specially expanded on Silk Road in Shah Abbas I’s reign (996-1083H.), played the role of producer, distributer and exporter in North, Center and South of Iran.