The Urban Book Series Aims and Scope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manifestation of Modernity in Iranian Public Squares: Baharestan Square (1826–1978)

Asma Mehan, Int. J. of Herit. Archit., Vol. 1, No. 3 (2017) 411–420 MANIFESTATION OF MODERNITY IN IRANIAN PUBLIC SQUARES: BAHARESTAN SQUARE (1826–1978) ASMA MEHAN Department of Architecture and Design, Politecnico Di Torino, Italy. ABSTRACT The concept of public square has changed significantly in Iran in recent centuries. This research inves- tigated how modernity is manifested in the public squares of Tehran. In this regard, Tehran has been chosen as the main concern, while in its short history as the capital of Iran, the city has been critically transformed: first because of constant urban development during the Qajar Dynasty and then due to its rapid growth during the late Pahavi era and second because of the culture of rapid renovation and reconstruction in contemporary public spaces. Considering these facts, the urban transformation of Baharestan Square as one of the most influencing public squares of Tehran in the recent century leads us to understand the process of Iranian modernization, which is totally different from common patterns of western modernity. Analysing the historical changes of Baharestan Square based on manuscripts, western travellers’ diaries, historical images and maps, from its formation till the Islamic Revolution (1978), shows how the traditional elements of the square as well as its form and function have been totally transformed. Analysing the spatial qualities of Baharestan Square clarifies that its special loca- tion near the first Iranian Parliament building, Sepahsalar Mosque and Negarestan Garden represents it as the first modern focal point in Iranian’s political and social life. Keywords: Baharestan Square, Iranian modernity, public square, Tehran. -

Semiology Study of Shrine Geometric Patterns of Damavand City of Tehran Province1

Special Issue INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND December 2015 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 Semiology Study of Shrine Geometric patterns of Damavand City of Tehran Province1 Atieh Youzbashi Masterof visual communication, Faculty of Art, Shahed University, Tehran, Iran [email protected] Seyed Nezam oldin Emamifar )Corresponding author) Assistant Professor of Faculty of Art, Shahed University, Tehran city, Iran [email protected] Abstract Remained works of decorative Arts in Islamic buildings, especially in religious places such as shrines, possess especial sprits and visual depth. Damavand city having very beautiful architectural works has been converted to a valuable treasury of Islamic architectural visual motifs. Getting to know shrines and their visual motifs features is leaded to know Typology, in Typology, Denotation and Connotation are the concept of truth. This research is based on descriptive and analytical nature and the collection of the data is in a mixture way. Sampling is in the form of non-random (optional) and there are 4 samples of geometric motifs of Damavand city of Tehran province and the analysis of information is qualitatively too. In this research after study of geometric designs used in this city shrines, the amount of this motifs confusion are known by semiotic concepts and denotation and connotation meaning is stated as well. At first the basic articles related to typology and geometric motifs are discussed. Discovering the meaning of these motifs requires a necessary deep study about geometric motifs treasury of believe and religious roots and symbolic meaning of this motifs. Geometric patterns with the centrality of the circle In drawing, the incidence abstractly and creating new combination is based on uniformly covering surfaces in order not to attract attention to designs independently creating an empty space also recalls “the principle of unity in diversity” and “diversity in unity”. -

Sample File P’ A Karachi S T Demavend J Oun to M R Doshan Tappan Muscatto Kand Airport

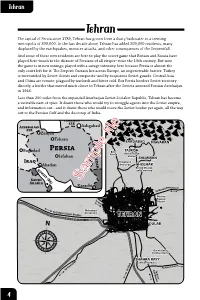

Tehran Tehran Tehran The capital of Persia since 1789, Tehran has grown from a dusty backwater to a teeming metropolis of 800,000. In the last decade alone, Tehran has added 300,000 residents, many displaced by the earthquakes, monster attacks, and other consequences of the Serpentfall. And some of these new residents are here to play the secret game that Britain and Russia have played here–much to the distaste of Persians of all stripes–since the 19th century. But now the game is in new innings; played with a savage intensity here because Persia is almost the only court left for it. The Serpent Curtain lies across Europe, an impenetrable barrier. Turkey is surrounded by Soviet clients and conquests–and by suspicious Soviet guards. Central Asia and China are remote, plagued by warlords and bitter cold. But Persia borders Soviet territory directly, a border that moved much closer to Tehran after the Soviets annexed Persian Azerbaijan in 1946. Less than 200 miles from the expanded Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic, Tehran has become Tbilisia veritable nest of spies. It draws those who would try to smuggle agents into the Soviet empire, and information out…and it draws those who would move the Soviet border yet again, all the way out to the PersianBaku Gulf and the doorstep of India.Tashkent T Stalinabad SSR A Ashgabad SSR Zanjan Tehran A S KabulSAADABAD NIAVARAN Damascus Baghdad P Evin TAJRISH Prison Red Air Force Isfahan Station SHEMIRAN I Telephone Jerusalem Abadan Exchange GHOLHAK British Mission and Cemetery R S Sample file P’ A Karachi S t Demavend J oun To M R Doshan Tappan MuscatTo Kand Airport Mehrabad Jiddah To Zanjan (Soviet Border) Aerodrome BombayTEHRAN N O DULAB Gondar A A Aden S Qul’eh Gabri Parthian Ruins SHAHRA RAYY Medieval Ruins To Garm Sar Salt Desert To Hamadan To Qom To Kavir 4 Tehran Tehran THE CHARACTER OF TEHRAN Tehran sits–and increasingly, sprawls–on the southern slopes of the Elburz Mountains, specifically Mount Demavend, an extinct volcano that towers 18,000 feet above sea level. -

Caravanserai

THE CARAVANSERAI This game has been designed as an extension kit to the OUTREMER/CROISADES sister games. The kit includes a new map (The Caravanserai), new counters for camels, this set of rules and additional scenarios. When not specified, the default rules of CROISADES apply (movement point allowance, charge rules, etc.). Many thanks to Bob Gingell for proofing these rules and suggesting many valuable enhancements. The Caravanserai – version 1.0 - 1992/2004 1 Table of Contents 1 The Caravanserai Map ........................................................................................................3 1.1 Description ..................................................................................................................................................3 1.2 Flat roofs......................................................................................................................................................3 1.3 The Alep gate...............................................................................................................................................4 1.4 The walls......................................................................................................................................................4 1.5 Terrain Type Summary...............................................................................................................................5 2 Camels....................................................................................................................................6 -

Zero Carbon & Low Energy Housing; Comparative Analysis of Two

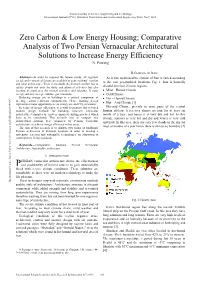

World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal of Civil, Structural, Construction and Architectural Engineering Vol:8, No:7, 2014 Zero Carbon & Low Energy Housing; Comparative Analysis of Two Persian Vernacular Architectural Solutions to Increase Energy Efficiency N. Poorang II. CLIMATE OF IRAN Abstract—In order to respond the human needs, all regional, As it was mentioned the climate of Iran is varied according social, and economical factors are available to gain residents’ comfort to the vast geographical locations, Fig. 1. Iran is basically and ideal architecture. There is no doubt the thermal comfort has to satisfy people not only for daily and physical activities but also divided into four climatic regions: creating pleasant area for mental activities and relaxing. It costs • Mild – Humid Climate energy and increases greenhouse gas emissions. • Cold Climate Reducing energy use in buildings is a critical component of • Hot – Humid Climate meeting carbon reduction commitments. Hence housing design • Hot – Arid Climate [1]. represents a major opportunity to cut energy use and CO2 emissions. In terms of energy efficiency, it is vital to propose and research Hot-arid Climate prevails in most parts of the central modern design methods for buildings however vernacular Iranian plateau, it receives almost no rain for at least six architecture techniques are proven empirical existing practices which month of a year, and hence it is very dry and hot. In this have to be considered. This research tries to compare two climate, summer is very hot and dry and winter is very cold architectural solution were proposed by Persian vernacular and hard. -

Tourism Boom by Islamic Art Spiritual Attractions in Iran Perspective Elements

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 7 No 4 S1 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy July 2016 Tourism Boom by Islamic Art Spiritual Attractions in Iran Perspective Elements Susan Khataei Assistant Professor, Department of Graphic Design, Faculty of Architecture and Urban Design, Shahid Rajaee Teacher Training University, Tehran, Iran Doi:10.5901/mjss.2016.v7n4s1p40 Abstract Iran is one of the ten first countries in the world on the subject of tourism attractions. Iran, the land of four seasons simultaneously, and historical and scientific - cultural buildings is of interest for many tourists. Various works of Islamic art in the perspective of Iran that have been arisen in different periods and regions all have the same message and truth and have a sign of coordination and the greatness of Islamic civilization and culture. The artistic unity that stems from ideological unity, is able to attract many audience and can transcends the boundaries of time and place and communicate spiritually with all its contacts and believers. Islamic art and architecture is derived from religious sources and has an appearance (form) and the inside. Forms are created to give meaning and generally in Islamic art, nothing is void of the "meaning". General feeling of foreign tourists by observing Islamic-Iranian monuments is along with surprise, admiration and a sense of spirituality. In this study, the role of decorations in mosques and shrines in Iranian - Islamic architecture to establish spiritual relationship with the audience is emphasized. This is an applied research with analytical descriptive method which have been done based on observation and documentary studies. -

Persian Heritage: a Significant Role in Achieving Sustainable Development

International Journal of Cultural Heritage E. Abedi, D. Kralj http://iaras.org/iaras/journals/ijch Persian heritage: A Significant Role in Achieving Sustainable Development ELAHEH ABEDI1, DAVORIN KRALJ2, A.M.Co., Tehran, IRAN1 ALMA MATER EUROPAEA, Slovenska 17, 2000 Maribor, SLOVENIA2, [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: In every country, heritage plays a significant role in achieving sustainable development. Iran, a high plateau located at latitudes in the range of 25-40 in an arid zone in the northern hemisphere of the East, is a vast country with different climatic zones. In the past, traditional builders have presented several logical climatic solutions in order to enhance human comfort. In fact, this emphasis has been one of the most important and fundamental features of Iranian architecture. To a significant extent, Iranian architecture has been based on climate, geography, available materials, and cultural beliefs. Therefore, traditional Iranian builders had to devise various techniques to enhance architectural sustainability through the use of natural materials, and they had to do so in the absence of modern technologies. Paper describes the principals and methods of vernacular architectural designs in Iran with given examples which is predominately focused on some eclectic ancient cities in Iran as Kashan, Isfahan, and Yazd. Design and technological considerations of past, such as sustainable performance of natural materials, optimum usage of available materials, and the use of wind and solar power, were studied in order to provide effective eco architectural designs to provide the architectural criteria and insights. This study will be beneficial to today architects in the design of architectural structures to provide human comfort and a sustainable life in adverse climatic conditions. -

Iran Map, the Middle East

THE REGIONAL GUIDE AND MAP OF Bandar-e Anzali Astaneh Lahijan Rasht Rud Sar GILAN Ramsar Manjil Tonekabon ChalusNow Shahr Qareh Tekan Amol Marshun Kojur Kuhin Qazvin MAZANDARAN Gach Sur Baladeh QAZVIN Ziaran Kahak IranHashtjerd Takestan Tairsh Karaj Tehran Nehavand Damavand Eslamshahr ReyEyvanki Robatkarim Zarand Varamin Saveh Manzariyeh Tafresh QOM Qom Weller 09103 WELLER CARTOGRAPHIC SERVICES LTD. is pleased to continue its efforts to provide map information on the internet for free but we are asking you for your support if you have the financial means to do so? With the introduction of Apple's iPhone and iPad using GoodReader you can now make our pdf maps mobile. If enough users can help us, we can update our existing material and create new maps. We have joined PayPal to provide the means for you to make a donation for these maps. We are asking for $5.00 per map used but would be happy with any support. Weller Cartographic is adding this page to all our map products. If you want this file without this request please return to our catalogue and use the html page to purchase the file for the amount requested. click here to return to the html page If you want a file that is print enabled return to the html page and purchase the file for the amount requested. click here to return to the html page We can sell you Adobe Illustrator files as well, on a map by map basis please contact us for details. click here to reach [email protected] Weller Cartographic Services Ltd. -

SSR JUNE__2016 Reduced.Pdf

Central University of Kashmir SELF STUDY REPORT Submitted to NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL (NAAC) Bangalore, India Table of Contents Content Page No. Executive Summary 1 Profile of the University 15 Criteria wise Inputs 25 Departmental Profiles 95 Appendices 281 Publications 282 Diversity in Faculty Recruitment 312 List of Court Cases 313 Executive Council 314 Academic Council 315 Finance Committee 317 Progression in Student Enrollment 318 Deans of various Schools 319 Members of IQAC 320 Administration 321 List of Students who qualified NET/JRF 322 Major Events 2010-15 323 Meetings of Various Academic/Administrative Boards 328 List showing students and other outreach activities during 2010-15 330 List Showing the awards received by the faculty during 2010-15 332 Central Universities Act 2009 333 Income and Expenditure 366 Central University of Kashmir Master Plan 371 Organizational Chart 372 Self Assessment Proforma 376 Executive Summary The University is presently operating through a number of campuses acquired on rent basis, owing to the fact that the construction of multi-storeyed buildings at the original site of the University Campus at Tulmulla (Ganderbal) has not yet been completed. Presently, the construction work is going on for pre-engineered 2-storeyed buildings which are expected to be completed within next six months. Hopefully, in the month of June-2016 some teaching departments may be shifted to Tulmulla (Ganderbal). At present, the three rented EXECUTIVE SUMMARY campuses are housing various teaching departments, the details of which are given as under: S. NO. NAME OF THE CAMPUS TOTAL BUILT-UP AREA DEPARTMENTS OPERATING IN THE CAMPUS. -

Mirrored Interiors of Iran Palaces and Holy Places Lustrzane Wnętrza Irańskich Pałaców I Świętych Miejsc

1/2019 PUA DOI: 10.4467/00000000PUA.19.006.10009 Olga Shkolna orcid.org/0000-0002-7245-6010 Borys Grinchenko Kyiv University Mirrored interiors of Iran palaces and holy places Lustrzane wnętrza irańskich pałaców i świętych miejsc Abstract Typical mirrored interiors of Iran from the eighteenth to the beginning of nineteenth century are discussed in this article. Aesthetic, plastic, architectural and design peculiarities of such places in the Persian tradition are researched using examples of the Golestan and Saadabad royal complexes in Tehran, religious sights of Qazvin (the holy place Hossein Imamzadeh grave mosque and Friday mosque); the mausoleum of the descendant of Abraham, the prophet Keydar in Ostan-e Zanjan; the Sayed Alaeddin Hussein mosque, the Shah Cheragh mosque (blue or mirrored mosque), and Ali Ibn Hamzeh mausoleum in Shiraz. Peculiarities of the addition of mirrored sculptural elements, precious stones and silver plates to amalgamated glass in such complexes are clarified. Keywords: Iran, mirrored interior, palaces, mosques, holy places, eighteenth to the beginning of nineteenth century Streszczenie W tym artykule omówiono typowe lustrzane wnętrza Iranu od XVIII do początku XIX wieku. Cechy estetyczne, plastyczne, architektoniczne i projektowe takich miejsc w tradycji perskiej są badane na przykładach królewskich kompleksów Golestan i Saadabad w Teheranie, zabytków religijnych w Ka- zwinie (mauzoleum Hossein Imamzadeh wraz z meczetem piątkowym); mauzoleum potomka Abra- hama, proroka Keydara w Ostan-e Zanjan; meczet Sayed Alaeddin Hussein, meczet Shah Cheragh (niebieski lub lustrzany meczet) i mauzoleum Ali Ibn Hamzeha w Shiraz. Artykuł wyjaśnia specyfikację dodawania lustrzanych elementów rzeźbiarskich, kamieni szlachetnych i srebrnych płytek do amal- gamowanego szkła w takich kompleksach. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Mohammadjavad Mahdavinejad, Ph.D. Associate Professor, Department of Architecture Faculty of Art and Architecture Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran [email protected] Cell: +98 912 214 2250 Tel: +98 21 8288 3739 Fax: +98 21 88008090 Personal Details Name: Mohammadjavad Surname: Mahdavinejad Scopus Author ID: 53164158600 h-index=13 Affiliation 2008 Assistant Professor, TMU (Tarbiat Modares University), Tehran, Iran. 2013 Associate Professor, TMU (Tarbiat Modares University), Tehran, Iran. 2020 Professor, TMU (Tarbiat Modares University), Tehran, Iran University Education 1996 Diploma, 1996, Exceptional Talented School, Iran. 2003 M.A. in Architecture, 2003, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran. 2007 Ph.D. in Architecture, 2007, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran. Honours and Honorific 2009 Honoured for Gifted Research -"Description of Principles of Identity in Islamic Architecture; Explanation of Identity in Islamic Architecture with Particular Reference to the Meaning of Taarof in Quranic Culture", National Institution of Elites, 28 & 29 Oct 2009, Tehran: The Islamic Republic of Iran International Conference Center 2010 "The Most Cited scientist of Iran in era of Art and Architecture", based on citations to articles in scientific journals and research of the country, The Institute of Avant- garde scientists of Iran 2010 "The Book-friend Citizen", The First Festival on Reading Development in the City of Tehran, Culture and Art Organization of Tehran Municipality, 7 Dec. 2010, Tehran: Arasbaran Conference Hall 2011 "The Devoted Architects to Islamic Architecture" – “Khadem-E-Masjid”, Deputy of Architecture and Urbanism of Tehran Municipality, 19 & 20 Apr. 2011, Tehran: Milad Tower Conference Halls 2011 "The Season Book of Islamic Republic of Iran – winter 2011", As the Author of "Urban Regeneration of Heritage of Future", June 21, 2011, Culture, Art & Architecture Research Center. -

Family Law in Islam : Divorce, Marriage and Women in the Muslim

Maaike Voorhoeve is Research Fellow at the University of A msterda m, where she teaches Islamic law and family law in the Muslim World. She holds a doctorate in legal anthropology, which concentrated upon contemporary Tunisian judicial practices in the field of divorce. She specialises in the legal anthropology of the Muslim World, focusing on Tunisia. VVoorhoeve_prelims.inddoorhoeve_prelims.indd i 22/28/2012/28/2012 33:21:49:21:49 PPMM VVoorhoeve_prelims.inddoorhoeve_prelims.indd iiii 22/28/2012/28/2012 33:21:49:21:49 PPMM FAMILY LAW IN ISLAM Divorce, Marriage and Women in the Muslim World Edited by Maaike Voorhoeve Voorhoeve_prelims.indd iii 2/28/2012 3:21:49 PM Published in 2012 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright Editorial selection and Introduction © 2012 Maaike Voorhoeve Copyright Individual Chapters © 2012 Susanne Dahlgren, Baudouin Dupret, Esther van Eijk, Christine Hegel-Cantarella, Arzoo Osanloo, Massimo Di Ricco, Nadia Sonneveld, Sarah Vincent-Grosso and Maaike Voorhoeve The right of Maaike Voorhoeve to be identifi ed as editor of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.