Patogh-Space Networks of Tehran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manifestation of Modernity in Iranian Public Squares: Baharestan Square (1826–1978)

Asma Mehan, Int. J. of Herit. Archit., Vol. 1, No. 3 (2017) 411–420 MANIFESTATION OF MODERNITY IN IRANIAN PUBLIC SQUARES: BAHARESTAN SQUARE (1826–1978) ASMA MEHAN Department of Architecture and Design, Politecnico Di Torino, Italy. ABSTRACT The concept of public square has changed significantly in Iran in recent centuries. This research inves- tigated how modernity is manifested in the public squares of Tehran. In this regard, Tehran has been chosen as the main concern, while in its short history as the capital of Iran, the city has been critically transformed: first because of constant urban development during the Qajar Dynasty and then due to its rapid growth during the late Pahavi era and second because of the culture of rapid renovation and reconstruction in contemporary public spaces. Considering these facts, the urban transformation of Baharestan Square as one of the most influencing public squares of Tehran in the recent century leads us to understand the process of Iranian modernization, which is totally different from common patterns of western modernity. Analysing the historical changes of Baharestan Square based on manuscripts, western travellers’ diaries, historical images and maps, from its formation till the Islamic Revolution (1978), shows how the traditional elements of the square as well as its form and function have been totally transformed. Analysing the spatial qualities of Baharestan Square clarifies that its special loca- tion near the first Iranian Parliament building, Sepahsalar Mosque and Negarestan Garden represents it as the first modern focal point in Iranian’s political and social life. Keywords: Baharestan Square, Iranian modernity, public square, Tehran. -

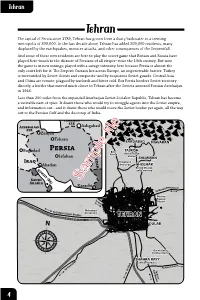

Sample File P’ A Karachi S T Demavend J Oun to M R Doshan Tappan Muscatto Kand Airport

Tehran Tehran Tehran The capital of Persia since 1789, Tehran has grown from a dusty backwater to a teeming metropolis of 800,000. In the last decade alone, Tehran has added 300,000 residents, many displaced by the earthquakes, monster attacks, and other consequences of the Serpentfall. And some of these new residents are here to play the secret game that Britain and Russia have played here–much to the distaste of Persians of all stripes–since the 19th century. But now the game is in new innings; played with a savage intensity here because Persia is almost the only court left for it. The Serpent Curtain lies across Europe, an impenetrable barrier. Turkey is surrounded by Soviet clients and conquests–and by suspicious Soviet guards. Central Asia and China are remote, plagued by warlords and bitter cold. But Persia borders Soviet territory directly, a border that moved much closer to Tehran after the Soviets annexed Persian Azerbaijan in 1946. Less than 200 miles from the expanded Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic, Tehran has become Tbilisia veritable nest of spies. It draws those who would try to smuggle agents into the Soviet empire, and information out…and it draws those who would move the Soviet border yet again, all the way out to the PersianBaku Gulf and the doorstep of India.Tashkent T Stalinabad SSR A Ashgabad SSR Zanjan Tehran A S KabulSAADABAD NIAVARAN Damascus Baghdad P Evin TAJRISH Prison Red Air Force Isfahan Station SHEMIRAN I Telephone Jerusalem Abadan Exchange GHOLHAK British Mission and Cemetery R S Sample file P’ A Karachi S t Demavend J oun To M R Doshan Tappan MuscatTo Kand Airport Mehrabad Jiddah To Zanjan (Soviet Border) Aerodrome BombayTEHRAN N O DULAB Gondar A A Aden S Qul’eh Gabri Parthian Ruins SHAHRA RAYY Medieval Ruins To Garm Sar Salt Desert To Hamadan To Qom To Kavir 4 Tehran Tehran THE CHARACTER OF TEHRAN Tehran sits–and increasingly, sprawls–on the southern slopes of the Elburz Mountains, specifically Mount Demavend, an extinct volcano that towers 18,000 feet above sea level. -

Landslide Zonation in Fasham Area of Tehran Province (Iran) Abstract Introduction

LANDSLIDE ZONATION IN FASHAM AREA OF TEHRAN PROVINCE (IRAN) Shadi Khoshdoni Farahani, Assoc.Prof.Dr.Md Nor Kamarudin, Dr. Mojgan Zarei Nejad Faculty of Geoinformation Science and Engineering, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia 81300 Skudai, Johor, Malaysia Email: [email protected] Faculty of Geoinformation Science and Engineering, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia 81300 Skudai, Johor , Malaysia Email: [email protected] GIS Center, Solvegatan 12, 223 62 Lund, Lund University, Sweden Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Tehran province which encircles the capital of the Islamic Republic of Iran is highly momentous from the politico- socio-economic-cultural aspects. This significance has instigated the implementation of the geological, geographical and climatological studies in this state in a comprehensive and precise manner. Fasham district in the north eastern part of Tehran province which is a geologically and geographically area has been opted out in this research for semi- detailed studies. the case studied in this research is the landslide in Fasham area. Iran is one of the highly landslide prone countries due to its particular geological, topographical and climatological conditions. Heavy financial lost are reported each year due to the landslide occurrence. The transpiration of these landslides occasionally brings about other death tolls and financial lost originating from earthquakes. Some of the factors affecting this phenomenon are as follows: the alteration of the slope amplitude, geotechnical and litho logical circumstances, earthquake and trembling, tectonics motions, structural alterations, pluvial effects and snow thawing, the extermination of the vegetation, land utilization alteration. The zone under studied is prone to landslide due to various reasons such as possessing special geological conditions and special geographical position. -

Into the Future on Three Wheels

Mitsubishi The 9th Grand Prix Winner A Bimonthly Review of the Mitsubishi Companies and Their People Around the World 2009-2010 Asian Children's2008- Enikki Festa 2009 Winners December & January Grand Prix Japan Humans are social beings. People live in groups. We Bangladeshis like to live with our parents, our brothers and sisters, our grandparents, and other relatives. In our family, I live with my brother, my parents, and my grandmother. We share each other’s joys and sorrows. That makes our lives fulfilling. Cycling * The above sentences contained in this Enikki has been translated from Bengali to English. Into the Future The 9th Grand Prix Winner on Three Wheels Sadia Islam Mowtushy Age:11 Girl People’s Republic of Bangladesh “Wrapping Up the Year with Toshikoshi Soba” oba is a Japanese noodle that is eaten in various ways longevity, because it is long and thin. There are many other depending on the season. In summer, soba is served cold explanations and no single theory can claim to be the definitive S and dipped in a chilled sauce; in winter, it comes in a hot truth, but this only adds to the mystique of toshikoshi soba. broth. Soba is often garnished with tasty tidbits, such as tempura shrimp, or with a bit of boiled spinach to add a touch of color. Soba has been a favorite of Japanese people for centuries and the popular buckwheat noodle has even secured a role in various Japanese traditions, including the New Year’s celebration. Japanese people commonly eat soba on New Year’s Eve, when the old year intersects with the new year, and this is known as toshikoshi or “year-crossing” soba. -

Alaska Senior Centers Open Back Up, but Carefully

A publication of Older Persons Action Group, Inc. Free Serving Alaskans 50+ Since 1978 Volume 44, Number 5 May 2021 Alaska senior centers open Can you transmit COVID if back up, but carefully. you are vaccinated?– page 5 – page 13 TRAVEL Exploring and Sleeping difficulties? Try a enjoying other cultures wearable tracker. – page 5 without leaving the country. – page 24 Get outside! Check out the festivals and other upcoming activities in our calendar of events. – page 17 Enjoy your Retirement! Chester Park is a safe, secure 55+ Adult Community. Our Member-Owners enjoy all the benefits of home ownership with none of the hassles. DON’T WAIT! UNITS SELL QUICKLY! Safe, Secure Senior Living For more information or a tour please call: 907-333-8844 www.chesterparkcoop.com EagleAbove: River’s Sheila Chris Fearon, Galloway 72, runsand orRichard walks the Brandon Eagle River relax Road in a seeming tropical oasis nearat his the house Mann every Leiser day. PartMemorial of his routine Greenhouse includes inpicking Anchorage. up roadside The facility is open to garbagethe public along the daily, way, 8 something a.m. to 3:30 he’s been p.m., doing free for admission. over 10 years. For “I more have aactivities, see the followingevents of calendarpeople that on honk page at me,19. Photo for Senior Voice by Michael Dinneen which is good. Usually.” Colin Tyler Photography Perspectives seniorvoicealaska.com Older Americans Month: Communities of Strength Alaska Commission on Aging This year’s theme is “Com- we can find strength, and something new allows us story, or service – we help munities of Strength,” rec- create a stronger future. -

Abstracta Iranica, Volume 42-43 | 2020 Farzaneh Hemmasi

Abstracta Iranica Revue bibliographique pour le domaine irano-aryen Volume 42-43 | 2020 Comptes rendus des publications de 2019-2020 Farzaneh Hemmasi. Tehrangeles Dreaming: Intimacy and Imagination in Southern California's Iranian Pop Music Laetitia Nanquette Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/abstractairanica/52754 DOI: 10.4000/abstractairanica.52754 ISBN: 1961-960X ISSN: 1961-960X Publisher: CNRS (UMR 7528 Mondes iraniens et indiens), Éditions de l’IFRI Electronic reference Laetitia Nanquette, “Farzaneh Hemmasi. Tehrangeles Dreaming: Intimacy and Imagination in Southern California's Iranian Pop Music”, Abstracta Iranica [Online], Volume 42-43 | 2020, document 2, Online since 15 April 2021, connection on 30 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/abstractairanica/ 52754 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/abstractairanica.52754 This text was automatically generated on 30 July 2021. Tous droits réservés Farzaneh Hemmasi. Tehrangeles Dreaming: Intimacy and Imagination in Southern ... 1 Farzaneh Hemmasi. Tehrangeles Dreaming: Intimacy and Imagination in Southern California's Iranian Pop Music Laetitia Nanquette REFERENCES Farzaneh Hemmasi. Tehrangeles Dreaming: Intimacy and Imagination in Southern California's Iranian Pop Music. Durham: Duke University Press, 2020, 264p., 40 illust. ISBN: 978-1-4780-0836-1 1 This book explores the production of pop music in Tehrangeles, a name given to Los Angeles by the Iranian diaspora, through its impact on Iranian identity. This form of pop music has been circulating widely abroad and in Iran for decades, and it is particularly relevant when considering cultural exchanges between Iran and its diaspora. Hemmasi explores how music producers have positioned themselves to reflect on the question of the Iranian nation. -

8 Day S &7 Nights

8 DAY S &7 NIGHTS Itinerary Code : 8D-94-US1 TEHRAN – SHIRAZ– ISFAHAN – ABYANEH – Date of issue: 17 AUG 2015 KASHAN Valid till March 4th 2016 Itinerary Note: “B” Breakfast / “L” Lunch / “D” Dinner / “A” Airplane /“T“Train/ “-” Not included Day 1 Arrival in Tehran at 22:20 meet and greet the Tehran tour guide. Check into the hotel then rest. B/-/-/A/- Day 2 Visit Tehran including: GolestanPalace Tehran (including two palaces), Jewellery Museum, B/L/D/-/- National Museum of Iran, Glassware Museum, Bagh-e Melli, Toopkhaneh Square, Grand Bazaar of Tehran. Return to hotel then rest. Day 3 Flight to Shiraz in early morning. Arrive to Tehran-Shiraz Shiraz. Visit Shiraz including: Arg of Karim B/L/D/A/- Khan, Qavam House, Eram Garden, Tomb of (924Km) Hafez, Tomb of Saadi, ZinatolMolk House, SarayeMoshir,Vakil Bazaar, Vakil Bath, Nasir olMolk Mosque. Day 4 Visit Persepolis, Naqsh-e Rajab, Naqsh-e Shiraz Rostam, Cube of Zoroaster, Afif Abad B/L/D/-/- Garden Day 5 Transfer to Isfahan. Visit Pasargad and The Shiraz- Isfahan Cypress of Abarkuh on the way. In the B/L/D/-/- afternoon, visit Isfahan famous bridges (425Km) (Khajoo&Siose Pol) No 495, Near Salehi Alley, Niavaran Ave. Tehran. Iran Website : www.ariantourist.com Tel : (+98 21) 22724121 Email : [email protected] Fax : (+98 21) 22744969 : www.facebook.com/ariantourist1 8 DAY S &7 NIGHTS Itinerary Code : 8D-94-US1 TEHRAN – SHIRAZ– ISFAHAN – ABYANEH – Date of issue: 17 AUG 2015 KASHAN Valid till March 4th 2016 Day 6 Visit Naqsh-e-Jahan Square, Ali Qapu, Imam Isfahan Mosque, Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque, B/L/D/-/- HashtBehesht, ChehelSotoun and Bazaar Day 7 Transfer to Tehran. -

War and Urban Sculptures of Tehran from an Objective Reality to a Subjective Matter*

Special Issue | War-Scape War and Urban Sculptures of Tehran From an Objective Reality to a Subjective Matter* Padideh Adelvand Abstract | The numerous wars such as the war against Russia in Qajar era, Ph.D. Candidate in Art Research, Alzahra University, the World War II in Pahlavi era and the 8-year war against Iraq in the Islamic Nazar research center, Tehran, Republic of Iran are experiences that the contemporary Iran has tasted its Iran. flavor. On the other hand, the experience of existing urban sculpture in [email protected] contemporary Tehran brings this question to mind that how the urban sculpture as a form of art, could reflect the war experience? And what approaches has been emerged in artworks over the representation of the war issue in different periods? This article is based on a documentary research that, the statues have been discussed as a document. According to the historical documents and books, a total of 47 dated sculptures related to the war issue from the Qajar era up to 1389SH. were studied. The results of this study showed that Tehran's sculptures can be divided into two main sections, "Qajar to the Islamic Revolution" and "Islamic Revolution to 2010". In the first section due to the much experiences and significant raids into the country, war is comprehended as the general definition means "aggression". Therefore, the government policy through the urban sculptures located in the squares - as a state element- is trying to project the military power; from the cannons, as the first examples, to the cavalry bodies of King. -

Active Tectonics of Tehran Area, Iran

J. Basic. Appl. Sci. Res., 2(4)3805-3819, 2012 ISSN 2090-4304 Journal of Basic and Applied © 2012, TextRoad Publication Scientific Research www.textroad.com Active Tectonics of Tehran Area, Iran Mehran Arian1 *, Nooshin Bagha2 1Associate professor, Department of Geology, Science and Research branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran 2Ph.D.Student, Department of Geology, Science and Research branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran ABSTRACT Tehran area (with 2398.5 km2 area) extended from the east of Damavand volcano to the west of Karaj city. This area is a major part of Tehran province and according to geologic division is a minor part of Alborz zone. This area is under compressive stress and shortening that caused by Arabia – Eurasia Convergence. This situation has confirmed by dominant existence of folded structures and thrust fault system. We have investigated geologic hazards of Tehran area, because this area is the most strategic part of Iran. The major faults have been investigated and have not been found any evidences to existence of north and south Rey faults. In the other hand, active tectonic of this area has been investigated and Mosha fault has been introduced as the most active fault. The high seismic potential has been distinguished by integration of structural geology and active tectonic studies. The evaluation of movement potential of the main faults in the current tectonic regime shows the North Tehran fault has % 90 potential to movement. In addition the hazard potentials of landslides, settlements, volcanism and dams have been introduced. Finally, geologic hazard map has been prepared and has been divided to10 zones with one to four ranking of risk. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 63/Wednesday, April 1, 2020/Notices

18334 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 63 / Wednesday, April 1, 2020 / Notices DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY a.k.a. CHAGHAZARDY, MohammadKazem); Subject to Secondary Sanctions; Gender DOB 21 Jan 1962; nationality Iran; Additional Male; Passport D9016371 (Iran) (individual) Office of Foreign Assets Control Sanctions Information—Subject to Secondary [IRAN]. Sanctions; Gender Male (individual) Identified as meeting the definition of the Notice of OFAC Sanctions Actions [NPWMD] [IFSR] (Linked To: BANK SEPAH). term Government of Iran as set forth in Designated pursuant to section 1(a)(iv) of section 7(d) of E.O. 13599 and section AGENCY: Office of Foreign Assets E.O. 13382 for acting or purporting to act for 560.304 of the ITSR, 31 CFR part 560. Control, Treasury. or on behalf of, directly or indirectly, BANK 11. SAEEDI, Mohammed; DOB 22 Nov ACTION: Notice. SEPAH, a person whose property and 1962; Additional Sanctions Information— interests in property are blocked pursuant to Subject to Secondary Sanctions; Gender SUMMARY: The U.S. Department of the E.O. 13382. Male; Passport W40899252 (Iran) (individual) Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets 3. KHALILI, Jamshid; DOB 23 Sep 1957; [IRAN]. Control (OFAC) is publishing the names Additional Sanctions Information—Subject Identified as meeting the definition of the of one or more persons that have been to Secondary Sanctions; Gender Male; term Government of Iran as set forth in Passport Y28308325 (Iran) (individual) section 7(d) of E.O. 13599 and section placed on OFAC’s Specially Designated [IRAN]. 560.304 of the ITSR, 31 CFR part 560. Nationals and Blocked Persons List Identified as meeting the definition of the 12. -

Mayors for Peace Member Cities 2021/10/01 平和首長会議 加盟都市リスト

Mayors for Peace Member Cities 2021/10/01 平和首長会議 加盟都市リスト ● Asia 4 Bangladesh 7 China アジア バングラデシュ 中国 1 Afghanistan 9 Khulna 6 Hangzhou アフガニスタン クルナ 杭州(ハンチォウ) 1 Herat 10 Kotwalipara 7 Wuhan ヘラート コタリパラ 武漢(ウハン) 2 Kabul 11 Meherpur 8 Cyprus カブール メヘルプール キプロス 3 Nili 12 Moulvibazar 1 Aglantzia ニリ モウロビバザール アグランツィア 2 Armenia 13 Narayanganj 2 Ammochostos (Famagusta) アルメニア ナラヤンガンジ アモコストス(ファマグスタ) 1 Yerevan 14 Narsingdi 3 Kyrenia エレバン ナールシンジ キレニア 3 Azerbaijan 15 Noapara 4 Kythrea アゼルバイジャン ノアパラ キシレア 1 Agdam 16 Patuakhali 5 Morphou アグダム(県) パトゥアカリ モルフー 2 Fuzuli 17 Rajshahi 9 Georgia フュズリ(県) ラージシャヒ ジョージア 3 Gubadli 18 Rangpur 1 Kutaisi クバドリ(県) ラングプール クタイシ 4 Jabrail Region 19 Swarupkati 2 Tbilisi ジャブライル(県) サルプカティ トビリシ 5 Kalbajar 20 Sylhet 10 India カルバジャル(県) シルヘット インド 6 Khocali 21 Tangail 1 Ahmedabad ホジャリ(県) タンガイル アーメダバード 7 Khojavend 22 Tongi 2 Bhopal ホジャヴェンド(県) トンギ ボパール 8 Lachin 5 Bhutan 3 Chandernagore ラチン(県) ブータン チャンダルナゴール 9 Shusha Region 1 Thimphu 4 Chandigarh シュシャ(県) ティンプー チャンディーガル 10 Zangilan Region 6 Cambodia 5 Chennai ザンギラン(県) カンボジア チェンナイ 4 Bangladesh 1 Ba Phnom 6 Cochin バングラデシュ バプノム コーチ(コーチン) 1 Bera 2 Phnom Penh 7 Delhi ベラ プノンペン デリー 2 Chapai Nawabganj 3 Siem Reap Province 8 Imphal チャパイ・ナワブガンジ シェムリアップ州 インパール 3 Chittagong 7 China 9 Kolkata チッタゴン 中国 コルカタ 4 Comilla 1 Beijing 10 Lucknow コミラ 北京(ペイチン) ラクノウ 5 Cox's Bazar 2 Chengdu 11 Mallappuzhassery コックスバザール 成都(チォントゥ) マラパザーサリー 6 Dhaka 3 Chongqing 12 Meerut ダッカ 重慶(チョンチン) メーラト 7 Gazipur 4 Dalian 13 Mumbai (Bombay) ガジプール 大連(タァリィェン) ムンバイ(旧ボンベイ) 8 Gopalpur 5 Fuzhou 14 Nagpur ゴパルプール 福州(フゥチォウ) ナーグプル 1/108 Pages -

Explanation of Effective Factors on Perceptual Organization Pattern of Area1 of Contemporary Tehran Based on Pattern Language Th

Archive of SID Explanation of Effective Factors on Perceptual Organization Pattern of Area 1 of contemporary Tehran Based on Pattern Language Theory Sina Mansouri a, Leila Karimifard b,*, Hossein Zabihi c, Seyed Hadi Ghoddusifar d a Department of Urban Engineering, Kish International Branch, Islamic Azad University, Kish Island, Iran b Department of Architecture, Faculty of Art and Architecture, South Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran c Department of Urban Engineering, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran d Department of Architecture, Faculty of Art and Architecture, South Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran Received: 08 July 2019- Accepted: 24 October 2019 Abstract District 1 of Tehran had experienced many changes during the past few decades and many of these changes had included few tangible matters, and never considered the public‟s concept of urban system pattern. The present study tried to explain the pattern language system of district 1 of Tehran, based on Christopher Alexander‟s theory of pattern language and adapt this theory to the public‟s concepts. This purpose was done by examining different theories belonging to prominent theoreticians, interviews, and maps obtained from the public and adapting them to the data of district 1 urban geographic system, live patterns were obtained according to pattern language theory. According to the findings of the research, among five major indexes of perceptual organization (node, edge, landmark, path, and district) from Kevin Lynch‟s view, nodes had more importance to the people of District 1, and other indexes stood at lower levels of importance. Based on a 4-page format that was used for the first time Nafeh in her thesis at Waterloo university, in field study format, these nodes were surveyed and analyzed by interviewing team on the pages, and consequently, 37 graduals and reticulated live patterns were obtained.