Manifestation of Modernity in Iranian Public Squares: Baharestan Square (1826–1978)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manifestation of Modernity in Iranian Public Squares: Baharestan Square (1826–1978)

Asma Mehan, Int. J. of Herit. Archit., Vol. 1, No. 3 (2017) 411–420 MANIFESTATION OF MODERNITY IN IRANIAN PUBLIC SQUARES: BAHARESTAN SQUARE (1826–1978) ASMA MEHAN Department of Architecture and Design, Politecnico Di Torino, Italy. ABSTRACT The concept of public square has changed significantly in Iran in recent centuries. This research inves- tigated how modernity is manifested in the public squares of Tehran. In this regard, Tehran has been chosen as the main concern, while in its short history as the capital of Iran, the city has been critically transformed: first because of constant urban development during the Qajar Dynasty and then due to its rapid growth during the late Pahavi era and second because of the culture of rapid renovation and reconstruction in contemporary public spaces. Considering these facts, the urban transformation of Baharestan Square as one of the most influencing public squares of Tehran in the recent century leads us to understand the process of Iranian modernization, which is totally different from common patterns of western modernity. Analysing the historical changes of Baharestan Square based on manuscripts, western travellers’ diaries, historical images and maps, from its formation till the Islamic Revolution (1978), shows how the traditional elements of the square as well as its form and function have been totally transformed. Analysing the spatial qualities of Baharestan Square clarifies that its special loca- tion near the first Iranian Parliament building, Sepahsalar Mosque and Negarestan Garden represents it as the first modern focal point in Iranian’s political and social life. Keywords: Baharestan Square, Iranian modernity, public square, Tehran. -

Pdf 129.08 K

The Role of Climate and Culture on the Formation of Courtyards in Mosques Hossein Soltanzadeh* Associate Professor of Architecture, Faculty of Art and Architecture, Tehran Central Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran Received: 23/05/2015; Accepted: 30/06/2015 Abstract The process regarding the formation of different mosque gardens and the elements that contribute to the respective process is the from the foci point of this paper. The significance of the topic lies in the fact that certain scholars have associated the courtyard in mosques with the concept of garden, and have not taken into account the elements that contribute to the development of various types of mosque courtyards. The theoretical findings of the research indicate that the conditions and instructions regarding the Jemaah [collective] prayers on one hand and the notion of exterior performance of the worshiping rites as a recommended religious precept paired with the cultural, environmental and natural factors on the other hand have had their share of founding the courtyards. This study employs the historical analytical approach since the samples are not contemporary. The dependant variables are culture and climate while the form of courtyard in the jame [congregational] mosque is the dependent variable. The statistical population includes the jame mosques from all over the Islamic world and the samples are picked selectively from among the population. The findings have demonstrated that the presence of courtyard is in part due to the nature of the prayers that are recommended to say in an open air, and in part because this is also favoured by the weather in most instances and on most days. -

Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov

SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV CHOKAN OF WORKS SELECTED SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV Pioneering Ethnographer and Historian of the Great Steppe When Chokan Valikhanov died of tuberculosis in 1865, aged only 29, the Russian academician Nikolai Veselovsky described his short life as ‘a meteor flashing across the field of oriental studies’. Set against his remarkable output of official reports, articles and research into the history, culture and ethnology of Central Asia, and more important, his Kazakh people, it remains an entirely appropriate accolade. Born in 1835 into a wealthy and powerful Kazakh clan, he was one of the first ‘people of the steppe’ to receive a Russian education and military training. Soon after graduating from Siberian Cadet Corps at Omsk, he was taking part in reconnaissance missions deep into regions of Central Asia that had seldom been visited by outsiders. His famous mission to Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan, which began in June 1858 and lasted for more than a year, saw him in disguise as a Tashkent mer- chant, risking his life to gather vital information not just on current events, but also on the ethnic make-up, geography, flora and fauna of this unknown region. Journeys to Kuldzha, to Issyk-Kol and to other remote and unmapped places quickly established his reputation, even though he al- ways remained inorodets – an outsider to the Russian establishment. Nonetheless, he was elected to membership of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society and spent time in St Petersburg, where he was given a private audience by the Tsar. Wherever he went he made his mark, striking up strong and lasting friendships with the likes of the great Russian explorer and geographer Pyotr Petrovich Semyonov-Tian-Shansky and the writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky. -

A Study of the Cultural Grounds in Formation and Growth of Ethnic Challenges in Azerbaijan, Iran

Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies Copyright 2018 2018, Vol. 5, No. 2, 64-76 ISSN: 2149-1291 A Study of the Cultural Grounds in Formation and Growth of Ethnic Challenges in Azerbaijan, Iran Mansour Salehi1, Bahram Navazeni2, Masoud Jafarinezhad3 This study has been conducted with the aim of finding the cultural bases of ethnic challenges in Azerbaijan and tried to provide the desired solutions for managing ethnic diversity in Iran and proper policy making in order to respect the components and the culture of the people towards increasing national solidarity. In this regard, this study investigates the cultural grounds of the formation and growth of ethnic challenges created and will be created after the Constitutional Revolution in Azerbaijan, Iran. Accordingly, the main question is that what is the most influential cultural ground in formation and growth of ethnic challenges in Azerbaijan? Research method was the in-depth interview, which was followed by an interview with 32 related experts, and after accessing all the results obtained, analysis of interview data and quotative analysis performed with in-depth interview. Findings of the research indicate that emphasis on the language of a country, cultural discrimination, and the non- implementation of Article 15 of the Constitution for the abandonment of Turkish speakers with 39% were the most important domestic cultural ground, and the impact of satellite channels in Turkey and Republic of Azerbaijan with 32% and superior Turkish identity in the vicinity of Azerbaijan with 31%, were the most important external grounds in formation and growth of ethnic challenges in Azerbaijan in Iran. -

Modernizing the Public Space: Gender Identities

MODERNIZING THE PUBLIC SPACE: GENDER IDENTITIES, MULTIPLE MODERNITIES, AND SPACE POLITICS IN TEHRAN A DISSERTATION IN Geosciences and Sociology Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by NAZGOL BAGHERI Bachelor of Architecture, 2004 Bachelor of Computer Science, 2006 Master of Urban Design, 2007 Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran Kansas City, Missouri 2013 © 2013 NAZGOL BAGHERI ALL RIGHTS RESERVED MODERNIZING THE PUBLIC SPACE: GENDER IDENTITIES, MULTIPLE MODERNITIES, AND SPACE POLITICS IN TEHRAN Nazgol Bagheri, Candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree University of Missouri - Kansas City, 2013 ABSTRACT After the Islamic Revolution of 1979 in Iran, surprisingly, the presence of Iranian women in public spaces dramatically increased. Despite this recent change in women’s presence in public spaces, Iranian women, like in many other Muslim-majority societies in the Middle East, are still invisible in Western scholarship, not because of their hijabs but because of the political difficulties of doing field research in Iran. This dissertation serves as a timely contribution to the limited post-revolutionary ethnographic studies on Iranian women. The goal, here, is not to challenge the mainly Western critics of modern and often privatized public spaces, but instead, is to enrich the existing theories through including experiences of a more diverse group. Focusing on the women’s experience, preferences, and use of public spaces in Tehran through participant observation and interviews, photography, architectural sketching as well as GIS spatial analysis, I have painted a picture of the complicated relationship between the architecture styles, the gendering of spatial boundaries, and the contingent nature of public spaces that goes beyond the simple dichotomy of female- male, private-public, and modern-traditional. -

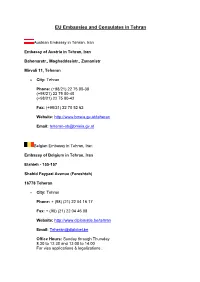

EU Embassies and Consulates in Tehran

EU Embassies and Consulates in Tehran Austrian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of Austria in Tehran, Iran Bahonarstr., Moghaddasistr., Zamanistr Mirvali 11, Teheran City: Tehran Phone: (+98/21) 22 75 00-38 (+98/21) 22 75 00-40 (+98/21) 22 75 00-42 Fax: (+98/21) 22 70 52 62 Website: http://www.bmeia.gv.at/teheran Email: [email protected] Belgian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of Belgium in Tehran, Iran Elahieh - 155-157 Shahid Fayyazi Avenue (Fereshteh) 16778 Teheran City: Tehran Phone: + (98) (21) 22 04 16 17 Fax: + (98) (21) 22 04 46 08 Website: http://www.diplomatie.be/tehran Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Sunday through Thursday 8.30 to 12.30 and 13.00 to 14.00 For visa applications & legalizations : Sunday through Tuesday from 8.30 to 11.30 AM Bulgarian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Bulgarian Embassy in Tehran, Iran IR Iran, Tehran, 'Vali-e Asr' Ave. 'Tavanir' Str., 'Nezami-ye Ganjavi' Str. No. 16-18 City: Tehran Phone: (009821) 8877-5662 (009821) 8877-5037 Fax: (009821) 8877-9680 Email: [email protected] Croatian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of the Republic of Croatia in Tehran, Iran 1. Behestan 25 Avia Pasdaran Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran City: Tehran Phone: 0098 21 258 9923 0098 21 258 7039 Fax: 0098 21 254 9199 Email: [email protected] Details: Covers the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Details: Ambassador: William Carbó Ricardo Cypriot Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of the Republic of Cyprus in Tehran, Iran 328, Shahid Karimi (ex. -

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

Name of Company Abadan Petrochemical Co. Afra Shimi Yazd

Name of Company 1 Abadan Petrochemical Co. 2 Afra Shimi Yazd Co. 3 Afzoon Ravan Co. 4 Akam Bitumen Co. 5 Alborz Chelic Iran Co. 6 Alborz Palayesh Eshtehard Co. 7 Alborz Rouzbehan Invesment 8 Ali Mohammad Jabarouti Trading 9 Ali Pardazan Atiye Co. 10 Ali Reza Zarenejad Trading 11 Alvan Sadegh Toos Co. 12 Apadana Petro Bazargan Co. 13 Aram Oil Co. 14 Arash Mahya Paraffin Manufacturing Co. 15 Araz Shimi Jolfa Co. 16 Aria Jam Oil Industries CO 17 Aria Sanat Behineh Co. 18 Arian Atlas Motor Oil Co. 19 Arkan Gas Co. 20 Armities Persia Co. 21 Arvand Shimi Sorour Co. 22 Aryaparaffin Co. 23 Asia Motor Oil Co. 24 Asia Zamen Kar Co. 25 Asiagilsonite Co. 26 Atlas Fam Sahand Paint Co. 27 Atra Crown Energy Co. 28 Ayegh Isfahan Co. 29 Azar Davam Yol Co. 30 Azar Ravan Saz Co. 31 Azaran Plast Afra Co. 32 Azarbayjan Eram Chemisry Co. 33 Baharan Shimi Boroujen Co. 34 Bana Gostar Karane Co. 35 Bayat Shahriar Chemical Industry 36 Behran Oil Co. 37 Behravan Kimia Novin Isatis Co. 38 Behravan Lorestan Co. 39 Behravan Shimi Rad Co. 40 Behtaran Shimi Rad Co. 41 Behtaz Shimi Co. 42 Binas Energy Co. 43 Blij Oil Co. 44 Bonyan Toseeh Rastin Co. 45 Butanerun Co. 46 Cabrogroup Co. 47 Carbon Tech Co. 48 Chemi Dor Salaf Co. 49 Corus Energy Co. 50 Crop Iran Co. 51 Damavand Motor Oil Co. 52 Dejpa Co. 53 Delta Shimi Co. 54 Deltafarayand Co. 55 Dena Esteghlal Co. 56 Dena Shimi Mehr Co. 57 Derakhsh Sign Co. -

Xvi. Yüzyil Anadolusu'nda Oğuz Boylarinin

Ç.Ü. Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, Cilt 26, Sayı 3, 2017, Sayfa 45-59 XVI. YÜZYIL ANADOLUSU’NDA OĞUZ BOYLARININ YERLEŞTİKLERİ YERLERİN SANCAKLARA DAĞILIMI Mehibe ŞAHBAZ* ÖZ Coğrafi konumu itibarıyla Anadolu tarihin her safahatında pek çok milletin ilgisini çekmiş ve bu yüzden dolayı da sayısız istilalara sahne olmuştur. Değişik din ve kültürlerin etkisi altında kalmıştır. Ancak bu istila ve kültür değişiklerinden hiç biri XI. yüzyılda başlayan ve Anadolu’nun Türkleşmesi ve İslâmlaşması ile sonuçlanan Oğuz (Türkmen) istilası kadar derin izler bırakamamıştır. Türk’ler tarihte birçok kollara ayrılır, Bu kollardan birisi olan Oğuz (Türkmen) adıyla bilinen kitlenin göç etmesi ve Anadolu’ya yerleşmesi, Büyük Selçuklu İmparatorluğu’ndaki siyasî ve demografik gelişmeleriyle ilgilidir. Bu gelişmeleri daha iyi anlayabilmek için Oğuzların Anadolu’ya gelmeden önceki durumlarına ve Anadolu’ya doğru yönelmelerinin sebeplerine kısada olsa temas etmek gerekir. Göktürk ve Uygur devletlerinin önemli bir unsuru olan Oğuzların boy teşkilatları, Selçuklu ve Osmanlı döneminde hüküm sürdükleri yerlere kültürlerini, gelenek ve göreneklerinin yanı sıra ruhi davranışlarını da getirerek, yerleştikleri bölgelerde mensup oldukları boyun oymağının adıyla anılmaktadırlar. Çalışmamızda Oğuzların Anadolu’ya nereden ve ne sebeple göç ettiğini ele almanın ötesinde başta Anadolu olmak üzere Oğuzların değişik coğrafyaları yurt edinmeleri üzerinde durulmuştur. X. asırdan XVI. asır’a kadar Anadolu’da yaşayan Oğuz boylarına mensup oymakların adlarının sancaklara dağılımını ulaşabildiğimiz kaynakların ışığı altında tespit etmeye çalıştık. Anahtar kelimeler: Oğuz, Türkmen, Boy, Yerleşim, Anadolu 16th CENTURY ANATOLIA OGHUZ TRIBES SETTLED TO STARBOARD OF THE PLACES DISTRIBUTION ABSTRACT Due to its geographical location, Anatolia has attracted many nations at every pace of history, and due to this, countless invasions have been the scene. -

Reading Comprehension Skills of Bilingual Children in Turkey

European Journal of Education Studies ISSN: 2501 - 1111 ISSN-L: 2501 - 1111 Available on-line at: www.oapub.org/edu doi: 10.5281/zenodo.572344 Volume 3 │ Issue 6 │ 2017 READING COMPREHENSION SKILLS OF BILINGUAL CHILDREN IN TURKEY Seher Bayati University of Ordu, Turkey Abstract: This study aims to compare the reading comprehension skills of the bilingual students studying at the 4th Grade of the Primary School with the monolingual students studying at the 4th Grade. With this purpose, 303 students were included from the Black Sea Region, where mainly monolingual students studied and 247 students were included from the Eastern and South-eastern Regions, where bilingual students studied. Furthermore, in order to expand the scope of the research, it was intended to find out the views of class teachers about the reading comprehension skills of bilingual students. So in the research, the mixed method and the parallel pattern converging from the patterns of the mixed method were used. The research result presented a significant difference between the reading comprehension skills of the monolingual 4th grade students from the Black Sea Region and the students from the Eastern and South- eastern Regions. This difference was in favour of the monolingual students. On the other hand, reading comprehension skills of the 4th graders in the Eastern and South- eastern Regions did not significantly differ within itself depending on bilingualism. Keywords: bilingual children, native language, reading comprehension, Turkish, Kurdish, Arabic 1. Introduction The official language and medium of instruction is Turkish in Turkey. According to Article 42 of the Constitution of the Republic of Turkey, “No language other than Turkish shall be taught as a mother tongue to Turkish citizens at any institutions of training or education. -

In the Name of God HISTORY

In The Name of God HISTORY The Packman Company was established in February 1975. In that year it was also registered in Tehran›s Registration Department. Packman›s construction and services company was active in building construction and its services in the early years of its formation.In 1976 in cooperation with (Brown Boveri and Asseck companies) some power plant mega projects was set up by the compa- ny.The company started its official activity in the filed of construction of High-Pressure Vessels such as Hot-Water Boilers , Steam Boilers , Pool Coil Tanks Softeners and Heat Exchangers from 1984. Packman Company was one of the first companies which supplied its customers with hot- water boilers which had the quality and standard mark.Packman has been export- ing its products to countries such as Uzbekistan, United Arab Emirates and other countries in the region. It is one of the largest producers of hot-water and steam boilers in the Middle East. Packman Company has got s degree from the Budget and Planning Organization in construction and services in the membership of some important associations such as: 1. Construction Services Industry Association 2. Industry Association 3. Construction Companies› Syndicate 4.Technical Department of Tehran University›s Graduates Association 5. Mechanical Engineering Association 6. Engineering Standard Association Packman Product: Steam boiler ( Fire tube ) Hot water boiler ( Fire tube ) Combination boile Water pack boiler Steam boiler ( water tube ) Hot water boiler (water tube) Boiler accessories Pressure vessel Water treatment equipment SOME OF CERTIFICATION ARE Manufacturer of Boilers, Thermal Oil Heaters, Heat Exchangers, Pressure Vessels, Storage Tanks & Industrial Water Treatment Equipments ,.. -

Taghipour M., Soltanzadeh H., Afkan K. B., 2015 the Role of Spatial Organization in the Typology of Shiraz (Iran) Residential Complexes

AES BIOFLUX Advances in Environmental Sciences - International Journal of the Bioflux Society The role of spatial organization in the typology of Shiraz (Iran) residential complexes Malihe Taghipour, Hossain Soltanzadeh, Kaveh B. Afkan Department of Architecture, College of Art and Architecture, Islamic Azad University, Tehran Central Branch, Tehran, Iran. Corresponding author: H. Soltanzadeh, [email protected] Abstract. The purpose of this study is to understand space organization, its different schemes, and its effect on the formation of residential complexes. This study was based on typology since typology can influence the classification of various organization schemes and since many other studies are also based on typology. The combined approach was implemented using library resources and comparative methodology. For this purpose, those residential complexes in Shiraz which complied with the project requirements were studied. Various residential complexes were classified in terms of scale and height by studying their aerial photographs, satellite maps and GIS pictures. Field visits were also conducted for this purpose. Based on the conducted studies, it was observed that the following organization schemes were implemented in Shiraz: 1) individual, 2) centralized, 3) clustered, 4) linear, and 5) mixed. Ultimately, typology tables were presented based on the organization scheme used as well as the building scale and height. The results showed that the clustered organization scheme was the governing organization scheme used in