Kristel Zilmer. Futhark 4 (2013)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{PDF EPUB} ~Download Stave Churches in Norway by Dan Lindholm Stave Churches in Norway by Dan Lindholm

{Read} {PDF EPUB} ~download Stave Churches in Norway by Dan Lindholm Stave Churches in Norway by Dan Lindholm. Stave churches are an important part of Norway’s architectural heritage. Urnes Stave Church in the Sognefjord is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. A stave church is a medieval wooden Christian church building. The name is derived from the buildings’ structure of post and lintel construction which is a type of timber framing, where the load-bearing posts are called stafr in Old Norse and stav in Norwegian. Two related church building types are also named for their structural elements, the post church and palisade church, but are often also called stave churches. Lom Stave Church is one of the biggest and most beautiful stave churches in Norway. It dates back to the 12th century and is still in use. The church is closed during church services. The church in Vågå is also worth a visit. In and around the Jotunheimen national park you can find a lot of interesting stave churches: 1225 – 1250 Hedalen in Valdres 1235 – 1265 Øystre Slidre in Valdres 1235 – 1265 Vestre Slidre in Valdres 1225 – 1250 Vang in Valdres 1250 – 1300 Vang in Valdres 1290 – 1320 Reinli in Valdres 1225 – 1250 Lærdal beside the Sognefjord 1150 – 1175 Luster beside the Sognefjord 1180 Sogndal beside the Sognefjord 1190 – 1225 Vik beside the Sognefjord 1210 – 1240 Lom 1100 – 1630 Vågå. Visit Stave Churches. Borgund Stave Church. Built around 1180 and is dedicated to the Apostle Andrew. The church is exceptionally well preserved and is one of the most distinctive stave churches in Norway. -

Henrik Williams. Scripta Islandica 65/2014

Comments on Michael Lerche Nielsen’s Paper HENRIK WILLIAMS The most significant results of Michael Lerche Nielsen’s contribution are two fold: (1) There is a fair amount of interaction between Scandinavians and Western Slavs in the Late Viking Age and Early Middle Ages — other than that recorded in later medieval texts (and through archaeology), and (2) This interaction seems to be quite peaceful, at least. Lerche Nielsen’s inventory of runic inscriptions and name material with a West Slavic connection is also good and very useful. The most important evidence to be studied further is that of the place names, especially Vinderup and Vindeboder. The former is by Lerche Niel sen (p. 156) interpreted to contain vindi ‘the western Slav’ which would mean a settlement by a member of this group. He compares (p. 156) it to names such as Saxi ‘person from Saxony’, Æistr/Æisti/Æist maðr ‘person from Estonia’ and Tafæistr ‘person from Tavastland (in Finland)’. The problem here, of course, is that we do not know for sure if these persons really, as suggested by Lerche Nielsen, stem ethnically from the regions suggested by their names or if they are ethnic Scandi navians having been given names because of some connection with nonScandi navian areas.1 Personally, I lean towards the view that names of this sort are of the latter type rather than the former, but that is not crucial here. The importance of names such as Æisti is that it does prove a rather intimate connection on the personal plane between Scandinavians and nonScan dinavians. -

Chronology and Typology of the Danish Runic Inscriptions

Chronology and Typology of the Danish Runic Inscriptions Marie Stoklund Since c. 1980 a number of important new archaeological runic finds from the old Danish area have been made. Together with revised datings, based for instance on dendrochronology or 14c-analysis, recent historical as well as archaeological research, these have lead to new results, which have made it evident that the chronology and typology of the Danish rune material needed adjustment. It has been my aim here to sketch the most important changes and consequences of this new chronology compared with the earlier absolute and relative ones. It might look like hubris to try to outline the chronology of the Danish runic inscriptions for a period of nearly 1,500 years, especially since in recent years the lack of a cogent distinction between absolute and relative chronology in runological datings has been criticized so severely that one might ask if it is possible within a sufficiently wide framework to establish a trustworthy chro- nology of runic inscriptions at all. However, in my opinion it is possible to outline a chronology on an interdisciplinary basis, founded on valid non-runo- logical, external datings, combined with reliable linguistic and typological cri- teria deduced from the inscriptions, even though there will always be a risk of arguing in a circle. Danmarks runeindskrifter A natural point of departure for such a project consists in the important attempt made in Danmarks runeindskrifter (DR) to set up an outline of an overall chro- nology of the Danish runic inscriptions. The article by Lis Jacobsen, Tidsfæst- else og typologi (DR:1013–1042 cf. -

Taosrewrite FINAL New Title Cover

Authenticity and Architecture Representation and Reconstruction in Context Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University, op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. Ph. Eijlander, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de Ruth First zaal van de Universiteit op maandag 10 november 2014 om 10.15 uur door Robert Curtis Anderson geboren op 5 april 1966 te Brooklyn, New York, USA Promotores: prof. dr. K. Gergen prof. dr. A. de Ruijter Overige leden van de Promotiecommissie: prof. dr. V. Aebischer prof. dr. E. Todorova dr. J. Lannamann dr. J. Storch 2 Robert Curtis Anderson Authenticity and Architecture Representation and Reconstruction in Context 3 Cover Images (top to bottom): Fantoft Stave Church, Bergen, Norway photo by author Ise Shrine Secondary Building, Ise-shi, Japan photo by author King Håkon’s Hall, Bergen, Norway photo by author Kazan Cathedral, Moscow, Russia photo by author Walter Gropius House, Lincoln, Massachusetts, US photo by Mark Cohn, taken from: UPenn Almanac, www.upenn.edu/almanac/volumes 4 Table of Contents Abstract Preface 1 Grand Narratives and Authenticity 2 The Social Construction of Architecture 3 Authenticity, Memory, and Truth 4 Cultural Tourism, Conservation Practices, and Authenticity 5 Authenticity, Appropriation, Copies, and Replicas 6 Authenticity Reconstructed: the Fantoft Stave Church, Bergen, Norway 7 Renewed Authenticity: the Ise Shrines (Geku and Naiku), Ise-shi, Japan 8 Concluding Discussion Appendix I, II, and III I: The Venice Charter, 1964 II: The Nara Document on Authenticity, 1994 III: Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage, 2003 Bibliography Acknowledgments 5 6 Abstract Architecture is about aging well, about precision and authenticity.1 - Annabelle Selldorf, architect Throughout human history, due to war, violence, natural catastrophes, deterioration, weathering, social mores, and neglect, the cultural meanings of various architectural structures have been altered. -

Vocalism in the Continental Runic Inscriptions

VOCALISM IN THE CONTINENTAL RUNIC INSCRIPTIONS Martin Findell, MA. Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2009 Volume II: Catalogue Notes on catalogue entries ................................................................................vii Designation of items .....................................................................................vii Concordance .................................................................................................vii Find-site ........................................................................................................vii Context ..........................................................................................................vii Provenance .................................................................................................. viii Datings ........................................................................................................ viii Readings ..................................................................................................... viii Images ............................................................................................................. x 1. Aalen ............................................................................................................... 1 2. Aquincum ....................................................................................................... 2 3. †Arguel ........................................................................................................... -

Practical Literacy and Christian Identity Are Two Sides of the Same Coin When Dealing with Late Viking Age Rune Stones

“Dead in White Clothes”: Modes of Christian Expression on Viking Age Rune Stones in Present-Day Sweden By Henrik Williams 2009 (Submitted version - the early author's version that has been submitted to the journal/publisher). Published as: Williams, Henrik: “Dead in White Clothes”: Modes of Christian Expression on Viking Age Rune Stones in Present-Day Sweden. I: Epigraphic Literacy and Christian Identity: Modes of Written Discourse in the Newly Christian European North. Ed. by Kristel Zilmer & Judith Jesch. (Utrecht Studies in Medieval Literacy 4.) Turnhout 2012. Pp. 137‒152. Practical literacy and Christian identity are two sides of the same coin when dealing with late Viking age rune stones. Reading the inscriptions on these monuments are by necessity not a straight-forward process for us today. The printed word we are familiar with is different in so many ways when compared to the usually very short and sometimes enigmatic messages we encounter in the form of runic carvings on rocks and cliffs throughout Scandinavia. The difficulties which we expect and take into account are not, however, primarily the main obstacles to our complete understanding of the rune stone texts. In one respect, these problems are superficial, dealing with formal restrictions of the media and the writing system. As is well known, the Viking age runic characters only numbered 16 (with the addition of three optional variants. Since the language(s) contained quite a few speech signs more than that, most runes could be use with more than one value and it is up to the reader to determine exactly which. -

Gudvangen, and a Passangerboat from Flåm/Aurland, Will Take You Through Some of the Most Spectacular Scenery in Norway

2018/2019 www.sognefjord.no Welcome to the Sognefjord – all year! The Sognefjord – Fjord Norways longest and most spectacular fjord with the Flåm railway, Jostedalen glacier, Jotunheimen national park, UNESCO Urnes stave church, local food, Aurlandsdalen valley, UNESCO fjord cruise, kayaking, glacier center, RIB-tours, hiking trails and other activities and accommodations with a fjord view. Deer farm, bathing facilities, fjord kayaking, family glacier hiking, museums, centers, playland and much more for the kids. The UNESCO Nærøyfjord was in 2004 titled by the National Geographic as “the worlds best unspoiled destination”. The Jotunheimen National park has fantastic hiking areas and Vettifossen - the most beautiful waterfall in Norway. There are marked hiking trails in Aurlandsdalen Valley and many other places around the Sognefjord. Glacier hiking at the Jostedalen glacier – the largest glacier on main land Europe – is an unique experience. There is Vorfjellet, Luster ©Vegard Aasen / VERI Media also three National tourist routes in the area – Sognefjellet, Aurlandsfjellet (“the Snowroad”) and Gaularfjellet, with attractions such as the viewpoints Stegastein and “Utsikten”. Summertime offers classic fjord experiences. In the autumn the air is clear and the fjord is Contents Contact us Tourist information dressed in beautiful autumn colors – the best time of the year for hiking and cycling. The Autumn and Winter 6 Visit Sognefjord AS Common phone(+47) 99 23 15 00 autumns shifts to the “Winter Fjord” with magical fjord light, alpine ski touring, snow shoe Sognefjord 8 Fosshaugane Campus Aurland: (+47) 91 79 41 64 walks, ski resorts, cross country skiing, fjord kayaking, RIB-safari, fjord cruises, the Flåm railway «Hiking buses»/Getting to Trolladalen 30 Flåm: (+47) 95 43 04 14 and guided tours to the magical blue ice caves under the glacier. -

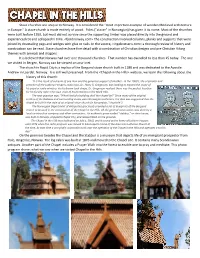

Stave Churches Are Unique to Norway. It Is Considered the "Most Important Example of Wooden Medieval Architecture in Europe." a Stave Church Is Made Entirely of Wood

Stave churches are unique to Norway. It is considered the "most important example of wooden Medieval architecture in Europe." A stave church is made entirely of wood. Poles ("staver" in Norwegian) has given it its name. Most of the churches were built before 1350, but most did not survive since the supporting timber was placed directly into the ground and experienced rot and collapsed in time. <fjordnorway.com> The construction involved columns, planks and supports that were joined by dovetailing pegs and wedges with glue or nails. In the source, <ingebretsens.com> a thorough review of history and construction can be read. Stave churches have fine detail with a combination of Christian designs and pre‐Christian Viking themes with animals and dragons. It is believed that Norway had over one thousand churches. That number has dwindled to less than 25 today. The one we visited in Bergen, Norway can be viewed on acuri.net. The church in Rapid City is a replica of the Borgund stave church built in 1180 and was dedicated to the Apostle Andrew in Laerdal, Norway. It is still well preserved. From the <Chapel‐in the‐Hills> website, we learn the following about the history of this church: "It is the result of a dream of one man and the generous support of another...In the 1960's, the originator and preacher of the Lutheran Vespers radio hour, Dr. Harry R. Gregerson, was looking to expand the scope of his popular radio ministry. As his dream took shape, Dr. Gregerson realized there was the perfect location for his facility right in his own state of South Dakota in the Black Hills. -

The Jacobson Family from Laerdal Parish, Sogn Og Fjordane County, Norway; Pioneer Norwegian Settlers in Greenwood Township, Vernon County, Wisconsin

THE JACOBSON FAMILY FROM LAERDAL PARISH, SOGN OG FJORDANE COUNTY, NORWAY PIONEER NORWEGIAN SETTLERS IN GREENWOOD TOWNSHIP, VERNON COUNTY, WISCONSIN BY LAWRENCE W. ONSAGER THE LEMONWEIR VALLEY PRESS Mauston, Wisconsin and Berrien Springs, Michigan 2018 COPYRIGHT © 2018 by Lawrence W. Onsager All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form, including electronic or mechanical means, information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the author. Manufactured in the United States of America. -----------------------------------Cataloging in Publication Data----------------------------------- Onsager, Lawrence William, 1944- The Jacobson Family from Laerdal Parish, Sogn og Fjordane County, Norway; Pioneer Norwegian Settlers in Greenwood Township, Vernon County, Wisconsin. Mauston, Wisconsin and Berrien Springs, Michigan: The Lemonweir Valley Press, 2018. 1. Greenwood Township, Vernon County, Wisconsin 2. Jacobson Family 3. Laerdal Township, Sogn og Fjordane County, Norway 4. Greenwood Norwegian-American Settlement in Vernon County, Wisconsin I. Title Tradition claims that the Lemonweir River was named for a dream. Prior to the War of 1812, an Indian runner was dispatched with a war belt of wampum with a request for the Dakotas and Chippewas to meet at the big bend of the Wisconsin River (Portage). While camped on the banks of the Lemonweir, the runner dreamed that he had lost his belt of wampum at his last sleeping place. On waking in the morning, he found his dream to be a reality and he hastened back to retrieve the belt. During the 1820's, the French-Canadian fur traders called the river, La memoire - the memory. The Lemonweir rises in the extensive swamps and marshes in Monroe County. -

Schulte M. the Scandinavian Dotted Runes

UDC 811.113.4 Michael Schulte Universitetet i Agder, Norge THE SCANDINAVIAN DOTTED RUNES For citation: Schulte M. The Scandinavian dotted runes. Scandinavian Philology, 2019, vol. 17, issue 2, pp. 264–283. https://doi.org/10.21638/11701/spbu21.2019.205 The present piece deals with the early history of the Scandinavian dotted runes. The medieval rune-row or fuþork was an extension of the younger 16-symbol fuþark that gradually emerged at the end of the Viking Age. The whole inventory of dotted runes was largely complete in the early 13th century. The focus rests on the Scandina- vian runic inscriptions from the late Viking Age and the early Middle Ages, viz. the period prior to AD 1200. Of particular interest are the earliest possible examples of dotted runes from Denmark and Norway, and the particular dotted runes that were in use. Not only are the Danish and Norwegian coins included in this discussion, the paper also reassesses the famous Oddernes stone and its possible reference to Saint Olaf in the younger Oddernes inscription (N 210), which places it rather safely in the second quarter of the 11th century. The paper highlights aspects of absolute and rela- tive chronology, in particular the fact that the earliest examples of Scandinavian dot- ted runes are possibly as early as AD 970/980. Also, the fact that dotted runes — in contradistinction to the older and younger fuþark — never constituted a normative and complete system of runic writing is duly stressed. In this context, the author also warns against overstraining the evidence of dotted versus undotted runes for dating medieval runic inscriptions since the danger of circular reasoning looms large. -

2015/2016 Welcome to the Sognefjord – All Year!

2015/2016 www.sognefjord.no Welcome to the Sognefjord – all year! The Sognefjord – Fjord Norways longest and most spectacular fjord with the Flåm railway, Jostedalen glacier, Jotunheimen national park, UNESCO Urnes stave church, local food, Aurlandsdalen valley, UNESCO fjord cruise, kayaking, glacier center, RIB-tours, hiking trails and other activities and accommodations with a fjord view. Motorikpark, deer farm, bathing facilities, fjord kayaking, family glacier hiking, museums, centers, playland and much more for the kids. The UNESCO Nærøyfjord was in 2004 titled by the National Geographic as “the worlds best unspoiled destination”. The Jotunheimen National park has fantastic hiking areas and Vettifossen - the most beautiful waterfall in Norway. There are marked hiking trails in Aurlandsdalen Valley and many other places around the Sognefjord. Glacier hiking at the Jostedalen glacier – the largest glacier on main land Europe – is an unique experience. There is Molden, Luster - © Terje Rakke, Nordic Life AS, Fjord Norway also three National tourist routes in the area – Sognefjellet, Aurlandsfjellet (“the Snowroad”) and Gaularfjellet, with attractions such as the viewpoints Stegastein and “Utsikten”. Summertime offers classic fjord experiences. In the autumn the air is clear and the fjord is Contents Contact us Tourist information dressed in beautiful autumn colors – the best time of the year for hiking and cycling. The Autumn and Winter 6 Visit Sognefjord AS Common phone (+47) 99 23 15 00 autumns shifts to the “Winter Fjord” with magical fjord light, alpine ski touring, snow shoe Sognefjord 8 Fosshaugane Campus Aurland: (+47) 91 79 41 64 walks, ski resorts, cross country skiing, fjord kayaking, RIB-safari, fjord cruises, the Flåm railway National Tourist Routes 12 Trolladalen 30 Flåm: (+47) 95 43 04 14 and guided tours to the magical blue ice caves under the glacier. -

Download the 2020 Scandinavia Travel Brochure

SCANDINAVIA 2020 TRAVEL BROCHURE BREKKE TOURS YOUR SCANDINAVIAN SPECIALIST SINCE 1956 Brekke Tours invites you to share our love of travel and join us to our own favorite corner of the world, Scandinavia! Brekke's 2020 escorted tours and independent travel options include a variety of activities and destinations across Scandinavia and beyond. It is our goal to make your travel dreams a reality while introducing you to breathtaking sites of natural beauty as well as the rich culture and history of the different countries in Scandinavia. Whether you choose to explore modern cities and quaint fjord-side villages on one of our escorted tours, travel independently to the mesmerizing Lofoten Islands or connect with your ancestors by visiting your family heritage sites, the staff of Brekke Tours is happy to help you create the perfect travel plan for you, your family and friends. Char Chaalse Linda Beth Molly Amanda Natalie Joey Diane WHY TRAVEL WITH BREKKE TOURS? Let our clients tell you why... “This was an amazing experience. The travel arrangements were so easy. Brekke Travel is #1. The Iceland extension that we did was also very good. The arrangements were wonderful. Thank you, Brekke Travel.” ~ E.J., Fergus Falls, MN “Brekke Tours was so professional and yet so personable to answer questions. The accommodations were excellent = A+. Tour guide was wonderful – fun and knowledgeable.” ~ G.L. and D.L., Choteau, MT “Got to see and do so much couldn’t have done on your own. Loved it all!” ~ 2019 Tour Participant “This was the trip of a lifetime and we enjoyed every moment.