Hungarian Archaeology E-Journal • 2021 Spring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-Day Adventist Church from the 1840S to 1889" (2010)

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2010 The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh- day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889 Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Snorrason, Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik, "The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889" (2010). Dissertations. 144. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/144 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 by Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Adviser: Jerry Moon ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 Name of researcher: Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jerry Moon, Ph.D. Date completed: July 2010 This dissertation reconstructs chronologically the history of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Norway from the Haugian Pietist revival in the early 1800s to the establishment of the first Seventh-day Adventist Conference in Norway in 1887. -

Traveling Portals Suspicious Item They Could Find Was His Diary

by a search the secret police had conducted in his house. The only TRAVelING PORTals suspicious item they could find was his diary. Apparently it did not contain enough evidence to take him to prison, and he even got it Mari Lending back. In an artistic rage, and trying to make sure that his personal notes could not be read again by anyone, he burned his diary. The Master and Margarita remained secret even after his death in 1940, and could not be published until 1966, when the phrase became In the early 1890s, the Times of London reported on a lawsuit on the 1 Times ( London ), more frequently used by dissidents to show their resistance to the pirating of plaster casts. With reference to a perpetual injunction June 2, 1892. state regime. In the early nineties, when the KGB archives were partly granted by the High Court of Justice, Chancery Division, it was 2 Times ( London ), opened, his diary was found. Apparently, during the confiscation, announced that “ various persons in the United Kingdom of Great February 14, 1894. the KGB had photocopied the diary before they returned it to the Britain and Ireland have pirated, and are pirating, casts and models ” author. made by “ D. BRUCCIANI and Co., of the Galleria delle Belle Arti, The best guardians are oftentimes ultimately the ones you would 40. Russell Street, Covent Garden ” and consequently severely vio least expect. lated the company’s copyright “ which is protected by statute. ” The defendant, including his workmen, servants, and agents, was warned against “ making, selling, or disposing of, or causing, or permitting to be made, sold, or disposed of, any casts or models taken, or copied, or only colourably different, from the casts or models, the sole right and property of and in which belongs to the said D. -

Telemark Cruise Ports Events: See

TELEMARK CRUISE PORTS Events: See www.visittelemark.com. Cruise season: All year. Average temperature: (Celsius) June 16o, July 18o, August 17o, September 15o Useful link: www.visittelemark.com/cruise. Cruise and port information: www.grenland-havn.no The Old Lighthouse at Jomfruland, Kragerø. Photo: Terje Rakke Vrangfoss Locks in the Telemark Canal. Photo: barebilder.no Folk Dancing. Photo: Til Telemark emphasize the importance of the district’s long 2012. Eidsborg Stave Church from 1250, one of the Rjukan – powerful nature and strong war history maritime traditions. The museum is situated on the best preserved examples of the 28 protected stave Duration: 8 hours. Capacity: 150. river bank next to Porsgrunn Town Museum, churches in Norway, is located next to the museum. Distance from port: 155 km. Rjukan is situated by the southern gateway to the Heddal with Norway’s most majestic stave church Morgedal and the history of skiing Hardanger Mountain Plateau, Norway’s largest Duration: 6 hours. Capacity: 180 Duration: 5-6 hours. Distance from port: 117 km. national park, and at the foot of the majestic Distance from port: 106 km Capacity: 300. mountain Gaustatoppen, 1883 m. A major tourist Heddal stave church is Norway’s largest and best The starting-point for a visit to the charming village attraction is the Norwegian Industrial Workers’ preserved stave church, built in the 1200s and still in of Morgedal is a tour of Norsk Skieventyr, a striking Museum at Vemork, where the dramatic Heavy Water use. It was a Catholic church until the reformation in building which houses a multimedia journey through Sabotage actions took place during World War II. -

Innkalling (.PDF, 0 B)

Møteinnkalling Utvalg: Utvalg for helse og omsorg Møtested: Kommunestyresalen, Nesset kommunehus Dato: 05.03.2019 Tidspunkt: 12.00 – 15.00 Eventuelt forfall må meldes snarest på tlf. 71 23 11 00. Møtesekretær innkaller vararepresentanter. Vararepresentanter møter etter nærmere beskjed. Svein Atle Roset Lill Kristin Stavik leder sekretær Saksliste – Utvalg for helse og omsorg, 05.03.2019 Utvalgs- Unntatt Arkiv- saksnr Innhold offentlighet saksnr PS 5/19 Godkjenning av protokoll fra forrige møte PS 6/19 Referatsaker RS 3/19 Helse og omsorg oppgaver i enheten - resultat 2018 2018/445 PS 7/19 Nye Molde kommune - videreføring av ordningen med lokal 2008/32 legevakt i Nesset. utplassering av satellitt. PS 5/19 Godkjenning av protokoll fra forrige møte PS 6/19 Referatsaker Helse og omsorg Møtereferat Dato: 14.02.2019 Til stede: Forfall: Referent: Jan Karsten Schjølberg Gjelder: Årsmelding helse og omsorg Sak: 2018/445-37 Møtetid: Møtested: Helse og omsorg Helse og omsorgstjenesten er en enhet med mange ulike fagprofesjoner som yter omfattende tjenester til mennesker i alle aldre. De fleste tjenester er lovpålagte og fortrinnsvis gitt med hjemmel i lov om helse og omsorgstjenester. Tjenester og oppgaver Pleie og omsorgstjenesten hadde pr. 31.12. totalt 48 institusjonsplasser ved Nesset omsorgssenter. Det pågår nå ombygging, og etter ombyggingen vil det også være 48 plasser, fordelt på sjukeheimen 30 plasser, demensavdeling 16 plasser og rehabiliteringsavdeling to plasser. Antall plasser ved Nesset omsorgssenter er sett i forhold til tidligere år redusert med åtte plasser. Bofellesskapet i Vistdal hadde pr. 31.12. døgnkontinuerlig bemanning. Det var ni beboere ved bofellesskapet. Enheten disponere også 16 gjennomgangsboliger/utleieleiligheter på Holtan og Myra. -

Krusifikset Og Madonnaskapet I Hedalen Stavkirke Undersøkelse 2006-2008

NIKU Rapport 25 Krusifikset og madonnaskapet i Hedalen stavkirke Undersøkelse 2006-2008 Mille Stein og Elisabeth Andersen Norsk institutt for kulturminneforskning Krusifikset og madonnaskapet i Hedalen stavkirke Undersøkelse 2006-2008 Mille Stein og Elisabeth Andersen NIKU Rapport 25 NIKU Rapport 25 Stein, Mille og Andersen, Elisabeth. 2008. Krusifikset Sammendrag Norsk institutt for kulturminneforskning og madonnaskapet i Hedalen stavkirke. Undersøkelse 20062008. – NIKU Rapport 25 NIKU ble etablert 1. september 1994 som del av Stif- Stein, Mille og Andersen, Elisabeth. 2008. Krusifikset og andre middelalderstykker i kirken: en madonnaskulptur telsen for naturforskning og kulturminneforskning, og en bekroning som forestiller en kirkebygning. Begge Oslo, desember 2008 madonnaskapet i Hedalen stavkirke. Undersøkelse 2006 NINA•NIKU. Fra 1. januar 2003 er instituttet en selv- 2008. NIKU Rapport 25. disse meget godt bevarte og ikke overmalte gjenstandene stendig stiftelse og del av det nyopprettede aksjesel- NIKU Rapport 25 er fra ca 1250. Undersøkelsen skulle ved hjelp av skapet Miljøalliansen som består av seks forsknings ISSN 15034895 Hedalen stavkirke i Valdres er fra 1160årene. Den ble tekniske metoder vurdere og eventuelt bekrefte teorien institutter og representerer en betydelig spesial- og ISBN 9788281010611 ombygget til korskirke i 1699. I annen halvdel av 1700 om at disse elementene opprinnelig hørte sammen og tverr faglig kompetanse til beste for norsk og interna- tallet fikk kirken ny altertavle. Den var laget av et over- hadde vært et madonnaskap. Undersøkelsen viser at sjonal miljøforskning. Rettighetshaver ©: Stiftelsen Norsk institutt for malt middelalderkrusifiks og korpus til et overmalt innsiden av korpus var imitasjonsforgylt. Avtegning av kulturminneforskning, NIKU NIKU skal være et nasjonalt og internasjonalt kom- middelalderskap. -

Cruise Norway Manual 2019/2020

Bacalhau da Noruega. Photo: Odd Inge Teige Håholmen. Photo: Classic Norway Opera in Kristiansund. Photo: Ken Alvin Jenssen late 1800s. See a blacksmith at work and visit the Kristiansund – the city of Clipfish OTHER ACTIVITIES: nearby museum’s café with its coffee roaster. Approx. Duration: 2 hrs Guided hiking tours or coastal walks 25 min. flat and easy walk from the cruise ship. The Norwegian Clipfish Museum is a large and Deep sea fishing well-preserved wharf dating back to 1749. The Diving at the Atlantic Ocean Road Opera/concert in Festiviteten Opera House wharf was used for the production of clipfish Seal Safari at the Atlantic Ocean Road Duration: 1,5-4 hrs (bacalhau, dried and salted cod), which became Sea Eagle Safari at Smøla Collect a musical souvenir from Kristiansund in important in the development of Kristiansund Visit a salmon farm at Hitra the beautiful opera house, either as an informal from the 18th century and up to the post- Indoor ice skating with Glühwein concert or as a theme cruise with opera/concert war period. A visit here will challenge all your Cruise on the Todal Fjord ticket included. It can all be tailored according senses: see, hear, touch, smell and taste! Nauståfossen waterfall and Svinviks’s arboretum to your wishes and interests (operetta, ballet, classical music, dance). Kristiansund houses «Bacalhau da Noruega» – Listen, look, taste! Selected shore excursions on Smøla Norway’s oldest opera, established in 1928. The Duration: 1 hr and Hitra (see next double page) are also annual Opera Fest Week in February comprises Let’s serve you some stories from our city – the available for ships calling at Kristiansund, around 50 performances and concerts. -

Church of Norway Pre

You are welcome in the Church of Norway! Contact Church of Norway General Synod Church of Norway National Council Church of Norway Council on Ecumenical and International Relations Church of Norway Sami Council Church of Norway Bishops’ Conference Address: Rådhusgata 1-3, Oslo P.O. Box 799 Sentrum, N-0106 Oslo, Norway Telephone: +47 23 08 12 00 E: [email protected] W: kirken.no/english Issued by the Church of Norway National Council, Communication dept. P.O. Box 799 Sentrum, N-0106 Oslo, Norway. (2016) The Church of Norway has been a folk church comprising the majority of the popu- lation for a thousand years. It has belonged to the Evangelical Lutheran branch of the Christian church since the sixteenth century. 73% of Norway`s population holds member- ship in the Church of Norway. Inclusive Church inclusive, open, confessing, an important part in the 1537. At that time, Norway Church of Norway wel- missional and serving folk country’s Christianiza- and Denmark were united, comes all people in the church – bringing the good tion, and political interests and the Lutheran confes- country to join the church news from Jesus Christ to were an undeniable part sion was introduced by the and attend its services. In all people. of their endeavor, along Danish king, Christian III. order to become a member with the spiritual. King Olav In a certain sense, the you need to be baptized (if 1000 years of Haraldsson, and his death Church of Norway has you have not been bap- Christianity in Norway at the Battle of Stiklestad been a “state church” tized previously) and hold The Christian faith came (north of Nidaros, now since that time, although a permanent residence to Norway in the ninth Trondheim) in 1030, played this designation fits best permit. -

Taosrewrite FINAL New Title Cover

Authenticity and Architecture Representation and Reconstruction in Context Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University, op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. Ph. Eijlander, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de Ruth First zaal van de Universiteit op maandag 10 november 2014 om 10.15 uur door Robert Curtis Anderson geboren op 5 april 1966 te Brooklyn, New York, USA Promotores: prof. dr. K. Gergen prof. dr. A. de Ruijter Overige leden van de Promotiecommissie: prof. dr. V. Aebischer prof. dr. E. Todorova dr. J. Lannamann dr. J. Storch 2 Robert Curtis Anderson Authenticity and Architecture Representation and Reconstruction in Context 3 Cover Images (top to bottom): Fantoft Stave Church, Bergen, Norway photo by author Ise Shrine Secondary Building, Ise-shi, Japan photo by author King Håkon’s Hall, Bergen, Norway photo by author Kazan Cathedral, Moscow, Russia photo by author Walter Gropius House, Lincoln, Massachusetts, US photo by Mark Cohn, taken from: UPenn Almanac, www.upenn.edu/almanac/volumes 4 Table of Contents Abstract Preface 1 Grand Narratives and Authenticity 2 The Social Construction of Architecture 3 Authenticity, Memory, and Truth 4 Cultural Tourism, Conservation Practices, and Authenticity 5 Authenticity, Appropriation, Copies, and Replicas 6 Authenticity Reconstructed: the Fantoft Stave Church, Bergen, Norway 7 Renewed Authenticity: the Ise Shrines (Geku and Naiku), Ise-shi, Japan 8 Concluding Discussion Appendix I, II, and III I: The Venice Charter, 1964 II: The Nara Document on Authenticity, 1994 III: Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage, 2003 Bibliography Acknowledgments 5 6 Abstract Architecture is about aging well, about precision and authenticity.1 - Annabelle Selldorf, architect Throughout human history, due to war, violence, natural catastrophes, deterioration, weathering, social mores, and neglect, the cultural meanings of various architectural structures have been altered. -

Heftet Ringerike 1956

111her•r P,i"f~rihl Muteum RINGERIKE 1956.57 RINGERIKES UNGDOMSLAG OG RINGERIKES MUSEUM E .EN HALS HARALD v,eE H .JØRGENSEN INNHOLD Omslag: Fm Hollela - etter akvarell av Harald Vibc. Elling M . Solheim: Rlngeriksdomen .. Fredrik Schjander: Skrift I sle In .. Per Hohle: Vassfaret og utvandringen Ul Amerika V. V.: Fra gård og grend . Peter L11se: Jan . E.F. Halvorsen: Litt om noen Rlngertksgårder I mellomalderen 12 Harald Vibe: To gamle kaller.. 17 To anon11me elever: Litt om den gamle Fylkesskolen på Ask 23 H. V.: Sør Hollerud . 24 V. V.: Referat fra Hole herTCd.styre .. 25 P. L.: Små stubber . 27 V. V.: Har A. 0 . Vinje Jaget teksten på Krokkleivtavlen. 28 P. L.: Rlngerlkshumor . 30 V. V.: Islendere på Ringerike . 31 RINGERIKE 1liingcriksdomcn Prost Oluf J ensse11 tilegnet Så åpner det gamle tempel sin dør og byder slektene inn: Kom og legg fra deg din syndebØr trette, kraftløse sinn. Hør hvor jeg kaller med malmen tung gammel og ung. Her har jeg stått gjennom seklenes gang, slekt etter slekt er blitt jord. Sorgen og gleden løftet sin sang. Evig er Herrens ord. Lovsangens toner stiger påny opp i mot sky. Kom da mitt folk i fra skog og grend, fra hverdag og strev med smått. Se det som falmet og slengtes hen, glemtes - men har oppstått. Vitner for oss i sin glans og prakt om Herrens makt. Ja dette er dagen jeg di·ømte om i lange og mørke år. Syng mine klokker din gledes~ljom så langt som klokker når. Tider skal komme ~ tider skal gå, Guds tempel stå. -

Menighetsbladet Nr. 1/2017

MENIGHETSBLADETMENIGHETSBLADET for E I D E B R E M S N E S K O R N S T A D K V E R N E S Nr.. 11 APRIL 2017 64. årgang Han er oppstanden, halleluja! Lov Ham og pris Ham, halleluja! Jesus, vår Frelser, lenkene brøt. Han har beseiret mørke og død. Lov Ham og pris Ham, vår Frelser og venn, han som gir synderen livet igjen. Halleluja! Vi skyldfrie er! Halleluja! Vår Jesus er her! (1. strofe og refreng av salme 204 i Norsk Salmebok. (Av Bernhard Kyamanywa/ Tanzaniansk melodi) Ny serie om bedehusene på Averøy og Eide Vi håper våre lesere kan hjelpe oss med å skaffe litt eller mer eller mye informasjon, Kårvåg bedehus omtrent som dette, eller andre histori- er/dokumentasjon på bedehusene på Averøy eller Eide. Tommy redaktør Bedehusene i kapell i 1934) Averøy Kjønnøy, Sandøya Sveggen, Futsetra, Solhøgda, Kirkevågen Bedehusene i Ekkilsøy kristelige Eide forsamlingshus, Vevang, Lyngstad, Bruvoll, Klippen Bolli,Visnes, Strand, Rokset, Meek, Stene, Øyen, Nås, Nås Lillemork, Kårvåg gamle bedehus, Eide Bådalen, Henda, Langøy (som ble Vet du om flere? Bedehuset slik det ser ut i dag. (Fotos besørget av Dagny Vågen) Bedehuset på Kårvåg ble bygget i 1925. enn det er i dag. Bedehustomta ble gitt i gave fra Vållå Det kan en se på (Kummervold). Bedehuset på Kårvåg er et bilder vi har funnet av de bedehusene her omkring som har til denne saken. vært og er mye i bruk. I alle år har det vært I dag er det på- møter, stevner, søndagsskole, basarer, bar- bygd med nytt inn- neforening, juletrefest og mange andre gangsparti og toa- arrangementer. -

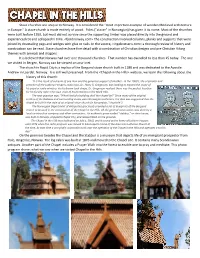

Stave Churches Are Unique to Norway. It Is Considered the "Most Important Example of Wooden Medieval Architecture in Europe." a Stave Church Is Made Entirely of Wood

Stave churches are unique to Norway. It is considered the "most important example of wooden Medieval architecture in Europe." A stave church is made entirely of wood. Poles ("staver" in Norwegian) has given it its name. Most of the churches were built before 1350, but most did not survive since the supporting timber was placed directly into the ground and experienced rot and collapsed in time. <fjordnorway.com> The construction involved columns, planks and supports that were joined by dovetailing pegs and wedges with glue or nails. In the source, <ingebretsens.com> a thorough review of history and construction can be read. Stave churches have fine detail with a combination of Christian designs and pre‐Christian Viking themes with animals and dragons. It is believed that Norway had over one thousand churches. That number has dwindled to less than 25 today. The one we visited in Bergen, Norway can be viewed on acuri.net. The church in Rapid City is a replica of the Borgund stave church built in 1180 and was dedicated to the Apostle Andrew in Laerdal, Norway. It is still well preserved. From the <Chapel‐in the‐Hills> website, we learn the following about the history of this church: "It is the result of a dream of one man and the generous support of another...In the 1960's, the originator and preacher of the Lutheran Vespers radio hour, Dr. Harry R. Gregerson, was looking to expand the scope of his popular radio ministry. As his dream took shape, Dr. Gregerson realized there was the perfect location for his facility right in his own state of South Dakota in the Black Hills. -

The Jacobson Family from Laerdal Parish, Sogn Og Fjordane County, Norway; Pioneer Norwegian Settlers in Greenwood Township, Vernon County, Wisconsin

THE JACOBSON FAMILY FROM LAERDAL PARISH, SOGN OG FJORDANE COUNTY, NORWAY PIONEER NORWEGIAN SETTLERS IN GREENWOOD TOWNSHIP, VERNON COUNTY, WISCONSIN BY LAWRENCE W. ONSAGER THE LEMONWEIR VALLEY PRESS Mauston, Wisconsin and Berrien Springs, Michigan 2018 COPYRIGHT © 2018 by Lawrence W. Onsager All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form, including electronic or mechanical means, information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the author. Manufactured in the United States of America. -----------------------------------Cataloging in Publication Data----------------------------------- Onsager, Lawrence William, 1944- The Jacobson Family from Laerdal Parish, Sogn og Fjordane County, Norway; Pioneer Norwegian Settlers in Greenwood Township, Vernon County, Wisconsin. Mauston, Wisconsin and Berrien Springs, Michigan: The Lemonweir Valley Press, 2018. 1. Greenwood Township, Vernon County, Wisconsin 2. Jacobson Family 3. Laerdal Township, Sogn og Fjordane County, Norway 4. Greenwood Norwegian-American Settlement in Vernon County, Wisconsin I. Title Tradition claims that the Lemonweir River was named for a dream. Prior to the War of 1812, an Indian runner was dispatched with a war belt of wampum with a request for the Dakotas and Chippewas to meet at the big bend of the Wisconsin River (Portage). While camped on the banks of the Lemonweir, the runner dreamed that he had lost his belt of wampum at his last sleeping place. On waking in the morning, he found his dream to be a reality and he hastened back to retrieve the belt. During the 1820's, the French-Canadian fur traders called the river, La memoire - the memory. The Lemonweir rises in the extensive swamps and marshes in Monroe County.