Gender Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 02 FEB GTR News

3 GTR Newsletter February 2016 2015 In This Issue: • GTR News and Events • BelKit VW Polo WRC Review • Moebius 61 Pontiac Review Mark Minter’s Resin Roswell Rod Grand Touring & Racing Auto Modelers Based in the Chicago, IL Northwest Suburbs 2002/2003 IPMS/USA Region 5 Chapter of the Year 2007, 2008 & 2015 IPMS/USA Region 5 Newsletter of the Year 2016 Meetings: Every 1st Saturday @ 7:00 p.m. Location alternates between member’s homes and the Algonquin Township Building Your current GTR Officers are: President: Joel Peters 847-714-3680 [email protected] Vice President: Steve Jahnke 847-516-8515 [email protected] Secretary/Contact: Chuck Herrmann 847-516-0211 [email protected] The GTR Newsletter is edited by Chuck Herrmann Please send all correspondence, newsletters, IPMS information, articles, reviews, comments, praise, and criticism to: Chuck Herrmann 338 Alicia Drive Cary, IL 60013 Unless indicated, all articles written by the editor. All errors, misspellings and inaccuracies, while the editor’s responsibility, are unintentional. Feel free to copy for any other nonprofit use. Visit and Join us on Facebook at GTR Auto Modelers 1 INDUSTRY NEWS Revell Germany 2016 New Kits Revell Germany has announced four all new 1/24 scale tool kits for 2016. All are set for fourth quarter 2016 release dates. GTR MAILBAG By Chuck Herrmann REAL WORLD First Female F1 Driver Passes Away From motorsport.com First is the Porsche 934RSR, two different kits. 07031 is the Jägermeister car, while 07032 is the Valliant version. (yes, this appears to be the same subject that Tamiya has recently released, in both markings! Too bad they couldn’t fill in some other gaps in the Porsche timeline…) Maria Teresa de Filippis, best known for having become Formula 1's first-ever female driver in the 1950s, has passed away at the age of 89. -

Autotest May 24Th 2007 CLUB CONTACTS CLUB CONTACTS Sevenoaks and District Motor Club Ltd

The Acorn June 2007 The Sevenoaks & District Motor Club Top Left: Darren Tyre - Class 1st Top Right: Chris Penfold - Class 1st Middle Left: Chris Judge - 5th Centre: Daren Hall - FTD Middle Right: Chris Rose - Class 1st Ralph Travers - Class 2nd Steve Thompson - Class 2nd Autotest May 24th 2007 CLUB CONTACTS CLUB CONTACTS Sevenoaks and District Motor Club Ltd. CLUB CONTACTS PRESIDENT: J Symes VICE PRESIDENT: V EIford ACORN MAGAZINE June 2007 The Editor, Committee and Club do not necessarily agree with items and opinions expressed within ACORN magazine OFFICERS and COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN; Chin, TROPHY RECORDS [email protected] KEEPER: DEPUTY CHAIR; Andy Elcomb, SECRETARY; [email protected] MEMBERSHIP SEC: TREASURER: Clive Cooke, [email protected] COMPETITION SEC; Ian Crocker, WEBMASTER: [email protected] SPEED LEAGUE Karen Webber, CHAMP CO-ORD: [email protected] RALLY SECRETARY: Iain Gibson, CHIEF MARSHAL: Philip Fawcett, [email protected] ACORN EDITOR; Dawn Travers, CHILD PROTECTION [email protected] OFFICER: SOCIAL SECRETARY: Daniel Whittington, [email protected] PRESS & PR: Suze Bisping, [email protected] PRESS & PR: Steve Thompson, [email protected] WEB ACORN: Ralph Travers, [email protected] Website - www.sevenoaksmotorclub.com PLEASE NOTE: COPY DATE FOR JULY ACORN WILL BE 18TH JUNE Wednesday 20th June 2007 Noggin & Natter from 8:30pm at The Lion, High Street, Farningham, Kent. DA4 0DP You can e-mail copy to [email protected] I will also accept copy on disc or CD-Rom; on paper -

Lella Lombardi March 26, 1943- March 3, 1992 Nationality: Italian Raced Between 1975-1988

Lella Lombardi March 26, 1943- March 3, 1992 Nationality: Italian Raced between 1975-1988 Origins: Maria Grazia “Lella” Lombardi was born in a small Italian village outside Turin in the midst of World War II. She came from modest means, with her father supporting the family through his work as town butcher. Growing up in rural Italy, Lella did not have much exposure to racing, or even cars, since her family’s fastest means of transportation was a 10-speed bicycle. Little did she know an injury during her teenage-years would lead her to a life of speed and adventure. Early Influences: Lombardi was a competitive and fearless child, excelling at the physically demanding sport of handball. Rumor has it that Lella’s first automobile experience was the result of a handball injury. Anecdotal evidence says Lombardi suffered a broken nose during a heated handball match and had to be driven to the nearest hospital. Instead of being concerned about her injury, Lombardi was awed by her first car ride. Impressed by the auto’s speed and driver’s ability to maneuver the busy streets of her hometown, she dreamed of one day having a car of her own and a racing career. A few years later, Lella finally saved up enough money to afford driving lessons and honed her skills behind the wheel of her boyfriend’s car. After passing her driving test, she bought a second-hand Fiat and began looking for racing opportunities. By coincidence Lombardi was introduced to a race car driver and began working with him, determined to learn all she could about the sport. -

Karl E. Ludvigsen Papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26

Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26 Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26 Miles Collier Collections Page 1 of 203 Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26 Title: Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Creator: Ludvigsen, Karl E. Call Number: Archival Collection 26 Quantity: 931 cubic feet (514 flat archival boxes, 98 clamshell boxes, 29 filing cabinets, 18 record center cartons, 15 glass plate boxes, 8 oversize boxes). Abstract: The Karl E. Ludvigsen papers 1905-2011 contain his extensive research files, photographs, and prints on a wide variety of automotive topics. The papers reflect the complexity and breadth of Ludvigsen’s work as an author, researcher, and consultant. Approximately 70,000 of his photographic negatives have been digitized and are available on the Revs Digital Library. Thousands of undigitized prints in several series are also available but the copyright of the prints is unclear for many of the images. Ludvigsen’s research files are divided into two series: Subjects and Marques, each focusing on technical aspects, and were clipped or copied from newspapers, trade publications, and manufacturer’s literature, but there are occasional blueprints and photographs. Some of the files include Ludvigsen’s consulting research and the records of his Ludvigsen Library. Scope and Content Note: The Karl E. Ludvigsen papers are organized into eight series. The series largely reflects Ludvigsen’s original filing structure for paper and photographic materials. Series 1. Subject Files [11 filing cabinets and 18 record center cartons] The Subject Files contain documents compiled by Ludvigsen on a wide variety of automotive topics, and are in general alphabetical order. -

The Bahn Stormer Volume XIX, Issue 5 -- June 2014

The Bahn Stormer Volume XIX, Issue 5 -- June 2014 Photo by Stewart Free The Official Publication of the Rally Sport Region - Porsche Club of America The Bahn Stormer Contents For Information on, or submissions to, The Bahn Stormer contact Mike O’Rear at The Official Page .......................................................3 [email protected] or 734-214-9993 Traction Control.......................................... ..............4 (Please put Bahn Stormer in the subject line) Calendar of Events........................................... .........5 Deadline: Normally by the end of the third Membership Page ....................................................9 week-end of the month. Time With Tim ........................................................11 Monjuïc Circuit .......................................................14 For Commercial Ads Contact Jim Christopher at Beginners’ Day DE ..................................................17 [email protected] Boxster Road Trip ....................................................19 Around The Zone ....................................................21 Advertising Rates (Per Year) Ramblings From a Life With Cars ............................23 Full Page: $650 Quarter Page: $225 ‘88 911s and a Bar of Soap .....................................24 Half Page: $375 Business Card: $100 Drivers’ Education ..................................................27 Club Meeting Minutes ............................................29 Classifieds ...............................................................30 -

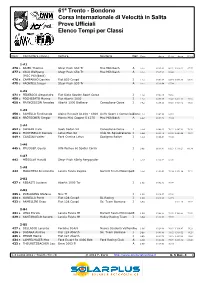

Elenco Tempi Per Classi

61ª Trento - Bondone Corsa Internazionale di Velocità in Salita Prove Ufficiali Elenco Tempi per Classi Num Conduttore (conc.) Vettura Scuderia Naz Classe Arrivo VMed Arrivo VMed 1-A1 478 e BAIER Thomas Steyr Puch 650 Tr Msc Mühlbach A 1-A1 15:30.69 66.92 15:16.22 67.97 477 e VALA Wolfgang Steyr Puch 650 Tr Msc Mühlbach A 1-A1 15:37.89 66.40 (MSC Mühlbach) 476 e CAMPARNÒ Daniele Fiat 850 Coupé I 1-A1 15:50.19 65.54 15:50.70 65.51 475 e PACHTEU Jurgen Steyr Puch 650 Tr A 1-A1 15:29.04 67.04 1-A2 471 e FEDERICO Alessandro Fiat Siata Spyder Sport Corsa I 1-A2 17:20.45 59.86 459 e FOCHESATO Marino Fiat Abarth 1000 I 1-A2 14:08.30 73.42 14:11.23 73.16 458 e FRANCESCON Amedeo Abarth 1000 Bialbero Conegliano Corse I 1-A2 15:04.53 68.85 14:38.72 70.88 1-A3 456 e RAMELLO Ferdinando Alpine Renault A110g - 1300 Aeffe Sport e ComunicazioneI 1-A3 16:47.00 61.85 455 e FRÖTSCHER Gregor Morris Mini Cooper S 1275 Msc Mühlbach A 1-A3 13:07.91 79.04 1-A4 452 e SEDRAN Italo Saab Sedan V4 Conegliano Corse I 1-A4 14:46.95 70.22 14:47.19 70.20 451 e MARTINELLO Daniele Lotus Elan S2 Club 91 Squadracorse I 1-A4 14:58.76 69.30 14:45.04 70.37 449 e CANZIAN Valter Ford Cortina Lotus Scaligera Rallye I 1-A4 13:56.57 74.45 1-A6 445 e PRUGGER Georg Alfa Romeo 6c Spider Corsa I 1-A6 16:58.47 61.15 17:05.27 60.74 1-A7 443 MÖSSLER Harald Steyr Puch König Bergspyder I 1-A7 12:38.72 82.09 1-A8 442 MARCHESI Alessandro Lancia Fulvia Zagato Borrett Team MotorsportI 1-A8 12:59.09 79.94 13:01.34 79.71 2-B2 437 e REBASTI Luciano Abarth 1000 Tcr I 2-B2 13:52.72 74.79 2-B3 435 e ZUBLASING Stefano Nsu Tt I 2-B3 15:16.17 67.98 434 e GONELLA Paolo Fiat 128 Coupé BL Racing I 2-B3 16:14.24 63.93 433 e ARMELLINI Enzo Fiat 128 Coupé Sc. -

PUBLICIS P1/25 Angl

2003 annual report Paris > In our own image—a new look for a new welcome on the world’s most stylish avenue, the Champs Elysées. I want something that does not yet exist Marcel Bleustein-Blanchet Founder of Publicis, 1906-1996 CONTENTS The events leading up to the creation The big picture: today’s Publicis of Publicis Groupe in its new form Groupe—its culture, structure, started with a string of acquisitions business and finances P.16. Fifteen from 2000 to 2002, among them Saatchi years of near-continuous growth in & Saatchi and selected specialized revenues, operating profit and net agencies. Publicis then merged with income P.20. Organic growth and Bcom3 in 2002, a move that catapulted moves into new markets backed by us into fourth place in the worldwide an innovative approach to motivating advertising industry. The year 2003 employees P.22. In 2003, Publicis was our first in this new position P.4. introduces its Peak Performance The main highlight of 2003 was the program P.23. Responsibility to successful integration of Bcom3, an shareholders: Publicis turns in Europe’s industry giant with an entirely different top stockmarket performance in the corporate culture P.6. Supervisory Board industry and one of the top three chair Elisabeth Badinter and Chairman worldwide P.28. The new Publicis and CEO Maurice Lévy comment on this Groupe helps clients win. An successful integration, highlighting the outstanding portfolio of leading brands, new Groupe’s capacity to pursue growth an excellent balance between local and without losing its identity P.8 & 10. world players P.32. -

November 2004 Ph: (02) 9864 – 8616 24 MM – D.Portelli 28 Classifieds

Club Lines Club Lines Producer Mr Ralph Watson (07) 3262 - 6227 Correspondence: P.O. Box 5601, Alexander Hills, QLD 4161 Faxes: 07 3882 0938 Australian Scalextric Racing and Collecting Club INC. www.scalextricaustralia. com In the spirit of friendly competition and mutual co-operation Committee Contents President Mr. John Corfield 1 Contents and Committee Ph: 02 9624 7141 2 Formatting Info/Future Issues/Competition Email: [email protected] 3 Armchair Racer 4 Gillham Book Review Vice-President & Public Officer 5 Gillham Book Review Mr. Andrew Moir 6 Princes Park – A History 7 Princes Park – A History Secretary Mr. Peter Drury 8 Scalex World Email: [email protected] 9 Riverside International Raceway 10 Riverside International Raceway ASRCC Membership/Web Site Liaison 11 Riverside International Raceway Mr. Bill Holmes/Mrs Jan Holmes 12 Riverside International Raceway Ph: 07 3207 2211 13 Readers Writes/Ecovandel Email: [email protected] 14 Leemans Hobbies Correspondence: P.O. Box 5601, 15 NSW Racing Alexander Hills, QLD 4161 16 Pymble Raceway Faxes: 07 3882 0938 17 Pymble Raceway 18 Pymble Raceway Treasurer Mr. Sid Terry 19 Pattoes Place Ph: 02 9769 – 1925 20 Budgie Bash 21 Brain Buster 25 MM – L.Terry Club Lines Editor Mr. Steve Terry 22 Slot Forum 26 Federation Park Email: [email protected] 23 Slot Forum 27 Federation Park Issue 130 1 November 2004 Ph: (02) 9864 – 8616 24 MM – D.Portelli 28 Classifieds Issue 130 2 November 2004 Club Lines Formatted Page In Future Issues For those wishing to submit articles of any size Members Moments from: - and shape for inclusion in the newsletter via the Jesse Thurlow Sid Terry web, here are a few guidelines. -

NCR PCA March 2013

March 2013 1 Northlander 2 Northlander March 2013 March 2013 1 Northlander NORTHLANDER NORTH COUNTRY REGION PORSCHE CLUB OF AMERICA Volume 36 Number 3 March 2013 Upcoming Events Editors 5 Calendar Ivy Cowles 14 NCR Fall Get-A-Way 603-767-6461 [email protected] 23 MAW Event at NHMS 24 Zone 1 Rally & Concours Hank Cowles 603-343-7575 30 NCR Autocross Season [email protected] 37 New Member Social Advertising 53 48 Hours of Watkins Glen Biff Gratton 55 Porsche Clash at The Glen 603-502-6023 [email protected] 56 NCR Car Control Clinic - NHMS 58 Zone 1 Autocross 2013 Website 59 2013 Porsche Gathering at LRP www.ncr-pca.org Departments 4 Board of Directors & Committee Chairs 6 President’s Message Statement of Policy 7 Editors’ Desk Northlander is the official publication of the North Country Region (NCR), Porsche 8 Membership Club of America (PCA). Opinions expressed herein are purely those of the writer and 9 Vice President are not to be construed as an endorsement or guarantee of the product or services by the Board of Directors of NCR. The 10 Drivers’ Ed editor reserves the right to edit all material submitted for publication. Material may be 49 Safety reprinted by PCA Regions without permission provided credit is given to the Northlander and the author. 52 The Mart The regular article and Advertising closing st date for the Northlander is the 1 of the 60 Advertisers’ Index month preceding the publication month. See page 60 for advertising rates. 2 Northlander March 2013 Features March 2013 15 Looking Back 25 Yankee Swap 2013 27 Saunder’s Saga #2 30 Do you recognize? 27 31 Northlander Hint / Riddle 38 Track Car Physics 101#2 39-42 Northlander’s centerfold - fold out 45 Targa Wrest Point 2013 48 KMC Tech Session 25 50 Visit to the Everglades Region 60 BTW 50 On the Cover Yikes...it is March! The cover was taken by David Churcher on his trip to Australia. -

Innovation, Sustainability and Management in Motorsports the Case of Formula E

Innovation, Sustainability and Management in Motorsports The Case of Formula E Hans Erik Næss Anne Tjønndal Innovation, Sustainability and Management in Motorsports “There’s probably no better sport than Formula E to present and study the science and practice of innovation within (motor)sport, and this book is a must read for those active within this fascinating area.” —Dr. Kristof de Mey, Sports Technology, Innovation & Business Developer at Ghent University Hans Erik Næss • Anne Tjønndal Innovation, Sustainability and Management in Motorsports The Case of Formula E Hans Erik Næss Anne Tjønndal Department of Leadership and Faculty of Social Sciences Organization Nord University Kristiania University College Bodø, Norway Oslo, Norway ISBN 978-3-030-74220-1 ISBN 978-3-030-74221-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74221-8 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2021. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. -

Special Issue Cosworth Dfv Hits 50

SPECIAL ISSUE COSWORTH DFV HITS 50 FORMULA 1’s UGLY FUTURE Halo will change F1 forever, but will it save lives? PLUS ROEBUCK ON THE BEST F1 ENGINE EVER BUILT HOW THE DFV BECAME A LE MANS WINNER SPECIAL ISSUE COSWORTH DFV HITS 50 FORMULA 1’s UGLY FUTURE Halo will change F1 forever, but will it save lives? COVER IMAGE Dean and Emma Wright/ PLUS ROEBUCK ON THE BEST F1 EN GINE EVER BUILT JULY 27 2017 HOW THE DFV BECAME A LE MANS WINNER UK £3.90 motorsport.tv COVER STORY 14 Is the halo right for Formula 1? PIT+PADDOCK 4 Fi h Column: Nigel Roebuck 6 Cosworth closing on F1 comeback 8 What Joest Mazda deal means for IMSA 11 Hungarian Grand Prix preview 12 Dieter Rencken: political animal 13 Feedback: your letters COSWORTH DFV AT 50 Halo grabs attention 20 Roebuck on what made it special 26 Tech: inside F1’s greatest engine 28 Stories of the DFV but engines are key 32 Stats: all the F1 winners 36 How it finally conquered Le Mans JUDGING BY OUR INBOX, THE NEWS THAT THE 40 The DFV in UK motorsport halo cockpit safety feature will be introduced to Formula 1 next season is one of the least popular moves of recent years. FEATURE 44 Silverstone Classic preview There can be little argument about the halo’s appearance: it is ugly. But, as Ben Anderson and Edd Straw investigate in our cover feature RACE CENTRE (page 14), the FIA felt it had to act. The push for improved safety 46 DTM; Super GT; Formula Renault Eurocup; can never end – arguments that ‘the drivers know the risks’ are IMSA; ELMS; NASCAR Cup no longer enough and haven’t been for a long time – but there is still some doubt that the halo is the right step forward. -

000 Turtle Soup 4

Nel corso degli anni, il progresso tecnologico ed il continuo The technological progress and continuous development, sviluppo hanno permesso di elevare il livello di fedeltà e which have been part of the progress of the past years, realismo fino a limiti impensabili fino a pochissimo tempo have been responsible for the increase of the existing level fa. of loyalty and trust between the manufacturer and the customer. Le immagini mostrano un moderno superkit in tutte le sue componenti. Un modello di questo tipo è composto da The images show a modern super kit in all its components. oltre 300 parti diverse prodotte in metallo bianco, tornitura, A model of this kind consists of over 300 different parts, fotoincisione, microfusione e materiale plastico. which are produced in white metal, turnings, photoetched process, microcasting and plastic materials. Per una migliore comprensione abbiamo posto in evidenza le varie tipologie di particolari con la descrizione dei In order to understand the product well, we have hilighted materiali con cui sono stati prodotti. the various typologies of the pieces, with a full description of the materials that have been used to produce them. Nelle pagine successive sono elencate in dettaglio le differenze fra i diversi kit di nostra produzione. The following pages list in detail, the existing differences between all the various kits that we have produced. Decalcomanie Carrozzeria e fondino scivolanti ad acqua in metallo bianco Water slide White metal decals body and chassis Particolari in metallo bianco White