Supporting Online Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lessons from 20 Years of Plant Genome Sequencing: an Unprecedented Resource in Need of More Diverse Representation

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.31.446451; this version posted May 31, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Lessons from 20 years of plant genome sequencing: an unprecedented resource in need of more diverse representation Authors: Rose A. Marks1,2,3, Scott Hotaling4, Paul B. Frandsen5,6, and Robert VanBuren1,2 1. Department of Horticulture, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA 2. Plant Resilience Institute, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA 3. Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701, South Africa 4. School of Biological Sciences, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, USA 5. Department of Plant and Wildlife Sciences, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, USA 6. Data Science Lab, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA Keywords: plants, embryophytes, genomics, colonialism, broadening participation Correspondence: Rose A. Marks, Department of Horticulture, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA; Email: [email protected]; Phone: (603) 852-3190; ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7102-5959 Abstract The field of plant genomics has grown rapidly in the past 20 years, leading to dramatic increases in both the quantity and quality of publicly available genomic resources. With an ever- expanding wealth of genomic data from an increasingly diverse set of taxa, unprecedented potential exists to better understand the evolution and genome biology of plants. -

Full of Beans: a Study on the Alignment of Two Flowering Plants Classification Systems

Full of beans: a study on the alignment of two flowering plants classification systems Yi-Yun Cheng and Bertram Ludäscher School of Information Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA {yiyunyc2,ludaesch}@illinois.edu Abstract. Advancements in technologies such as DNA analysis have given rise to new ways in organizing organisms in biodiversity classification systems. In this paper, we examine the feasibility of aligning two classification systems for flowering plants using a logic-based, Region Connection Calculus (RCC-5) ap- proach. The older “Cronquist system” (1981) classifies plants using their mor- phological features, while the more recent Angiosperm Phylogeny Group IV (APG IV) (2016) system classifies based on many new methods including ge- nome-level analysis. In our approach, we align pairwise concepts X and Y from two taxonomies using five basic set relations: congruence (X=Y), inclusion (X>Y), inverse inclusion (X<Y), overlap (X><Y), and disjointness (X!Y). With some of the RCC-5 relationships among the Fabaceae family (beans family) and the Sapindaceae family (maple family) uncertain, we anticipate that the merging of the two classification systems will lead to numerous merged solutions, so- called possible worlds. Our research demonstrates how logic-based alignment with ambiguities can lead to multiple merged solutions, which would not have been feasible when aligning taxonomies, classifications, or other knowledge or- ganization systems (KOS) manually. We believe that this work can introduce a novel approach for aligning KOS, where merged possible worlds can serve as a minimum viable product for engaging domain experts in the loop. Keywords: taxonomy alignment, KOS alignment, interoperability 1 Introduction With the advent of large-scale technologies and datasets, it has become increasingly difficult to organize information using a stable unitary classification scheme over time. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/07/2021 08:53:11AM Via Free Access 130 IAWA Journal, Vol

IAWA Journal, Vol. 27 (2), 2006: 129–136 WOOD ANATOMY OF CRAIGIA (MALVALES) FROM SOUTHEASTERN YUNNAN, CHINA Steven R. Manchester1, Zhiduan Chen2 and Zhekun Zhou3 SUMMARY Wood anatomy of Craigia W.W. Sm. & W.E. Evans (Malvaceae s.l.), a tree endemic to China and Vietnam, is described in order to provide new characters for assessing its affinities relative to other malvalean genera. Craigia has very low-density wood, with abundant diffuse-in-aggre- gate axial parenchyma and tile cells of the Pterospermum type in the multiseriate rays. Although Craigia is distinct from Tilia by the pres- ence of tile cells, they share the feature of helically thickened vessels – supportive of the sister group status suggested for these two genera by other morphological characters and preliminary molecular data. Although Craigia is well represented in the fossil record based on fruits, we were unable to locate fossil woods corresponding in anatomy to that of the extant genus. Key words: Craigia, Tilia, Malvaceae, wood anatomy, tile cells. INTRODUCTION The genus Craigia is endemic to eastern Asia today, with two species in southern China, one of which also extends into northern Vietnam and southeastern Tibet. The genus was initially placed in Sterculiaceae (Smith & Evans 1921; Hsue 1975), then Tiliaceae (Ren 1989; Ying et al. 1993), and more recently in the broadly circumscribed Malvaceae s.l. (including Sterculiaceae, Tiliaceae, and Bombacaceae) (Judd & Manchester 1997; Alverson et al. 1999; Kubitzki & Bayer 2003). Similarities in pollen morphology and staminodes (Judd & Manchester 1997), and chloroplast gene sequence data (Alverson et al. 1999) have suggested a sister relationship to Tilia. -

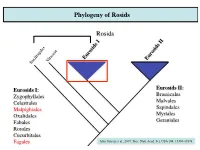

Phylogeny of Rosids! ! Rosids! !

Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Alnus - alders A. rubra A. rhombifolia A. incana ssp. tenuifolia Alnus - alders Nitrogen fixation - symbiotic with the nitrogen fixing bacteria Frankia Alnus rubra - red alder Alnus rhombifolia - white alder Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia - thinleaf alder Corylus cornuta - beaked hazel Carpinus caroliniana - American hornbeam Ostrya virginiana - eastern hophornbeam Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Fagaceae (Beech or Oak family) ! Fagaceae - 9 genera/900 species.! Trees or shrubs, mostly northern hemisphere, temperate region ! Leaves simple, alternate; often lobed, entire or serrate, deciduous -

ABSTRACTS 117 Systematics Section, BSA / ASPT / IOPB

Systematics Section, BSA / ASPT / IOPB 466 HARDY, CHRISTOPHER R.1,2*, JERROLD I DAVIS1, breeding system. This effectively reproductively isolates the species. ROBERT B. FADEN3, AND DENNIS W. STEVENSON1,2 Previous studies have provided extensive genetic, phylogenetic and 1Bailey Hortorium, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853; 2New York natural selection data which allow for a rare opportunity to now Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY 10458; 3Dept. of Botany, National study and interpret ontogenetic changes as sources of evolutionary Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, novelties in floral form. Three populations of M. cardinalis and four DC 20560 populations of M. lewisii (representing both described races) were studied from initiation of floral apex to anthesis using SEM and light Phylogenetics of Cochliostema, Geogenanthus, and microscopy. Allometric analyses were conducted on data derived an undescribed genus (Commelinaceae) using from floral organs. Sympatric populations of the species from morphology and DNA sequence data from 26S, 5S- Yosemite National Park were compared. Calyces of M. lewisii initi- NTS, rbcL, and trnL-F loci ate later than those of M. cardinalis relative to the inner whorls, and sepals are taller and more acute. Relative times of initiation of phylogenetic study was conducted on a group of three small petals, sepals and pistil are similar in both species. Petal shapes dif- genera of neotropical Commelinaceae that exhibit a variety fer between species throughout development. Corolla aperture of unusual floral morphologies and habits. Morphological A shape becomes dorso-ventrally narrow during development of M. characters and DNA sequence data from plastid (rbcL, trnL-F) and lewisii, and laterally narrow in M. -

Phylogenetic Relationships in the Order Cucurbitales and a New Classification of the Gourd Family (Cucurbitaceae)

Schaefer & Renner • Phylogenetic relationships in Cucurbitales TAXON 60 (1) • February 2011: 122–138 TAXONOMY Phylogenetic relationships in the order Cucurbitales and a new classification of the gourd family (Cucurbitaceae) Hanno Schaefer1 & Susanne S. Renner2 1 Harvard University, Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, 22 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, U.S.A. 2 University of Munich (LMU), Systematic Botany and Mycology, Menzinger Str. 67, 80638 Munich, Germany Author for correspondence: Hanno Schaefer, [email protected] Abstract We analysed phylogenetic relationships in the order Cucurbitales using 14 DNA regions from the three plant genomes: the mitochondrial nad1 b/c intron and matR gene, the nuclear ribosomal 18S, ITS1-5.8S-ITS2, and 28S genes, and the plastid rbcL, matK, ndhF, atpB, trnL, trnL-trnF, rpl20-rps12, trnS-trnG and trnH-psbA genes, spacers, and introns. The dataset includes 664 ingroup species, representating all but two genera and over 25% of the ca. 2600 species in the order. Maximum likelihood analyses yielded mostly congruent topologies for the datasets from the three genomes. Relationships among the eight families of Cucurbitales were: (Apodanthaceae, Anisophylleaceae, (Cucurbitaceae, ((Coriariaceae, Corynocarpaceae), (Tetramelaceae, (Datiscaceae, Begoniaceae))))). Based on these molecular data and morphological data from the literature, we recircumscribe tribes and genera within Cucurbitaceae and present a more natural classification for this family. Our new system comprises 95 genera in 15 tribes, five of them new: Actinostemmateae, Indofevilleeae, Thladiantheae, Momordiceae, and Siraitieae. Formal naming requires 44 new combinations and two new names in Cucurbitaceae. Keywords Cucurbitoideae; Fevilleoideae; nomenclature; nuclear ribosomal ITS; systematics; tribal classification Supplementary Material Figures S1–S5 are available in the free Electronic Supplement to the online version of this article (http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/iapt/tax). -

Field Identification of the 50 Most Common Plant Families in Temperate Regions

Field identification of the 50 most common plant families in temperate regions (including agricultural, horticultural, and wild species) by Lena Struwe [email protected] © 2016, All rights reserved. Note: Listed characteristics are the most common characteristics; there might be exceptions in rare or tropical species. This compendium is available for free download without cost for non- commercial uses at http://www.rci.rutgers.edu/~struwe/. The author welcomes updates and corrections. 1 Overall phylogeny – living land plants Bryophytes Mosses, liverworts, hornworts Lycophytes Clubmosses, etc. Ferns and Fern Allies Ferns, horsetails, moonworts, etc. Gymnosperms Conifers, pines, cycads and cedars, etc. Magnoliids Monocots Fabids Ranunculales Rosids Malvids Caryophyllales Ericales Lamiids The treatment for flowering plants follows the APG IV (2016) Campanulids classification. Not all branches are shown. © Lena Struwe 2016, All rights reserved. 2 Included families (alphabetical list): Amaranthaceae Geraniaceae Amaryllidaceae Iridaceae Anacardiaceae Juglandaceae Apiaceae Juncaceae Apocynaceae Lamiaceae Araceae Lauraceae Araliaceae Liliaceae Asphodelaceae Magnoliaceae Asteraceae Malvaceae Betulaceae Moraceae Boraginaceae Myrtaceae Brassicaceae Oleaceae Bromeliaceae Orchidaceae Cactaceae Orobanchaceae Campanulaceae Pinaceae Caprifoliaceae Plantaginaceae Caryophyllaceae Poaceae Convolvulaceae Polygonaceae Cucurbitaceae Ranunculaceae Cupressaceae Rosaceae Cyperaceae Rubiaceae Equisetaceae Rutaceae Ericaceae Salicaceae Euphorbiaceae Scrophulariaceae -

Taxonomic Update and Habitat Status to Byttneria Herbacea from Peninsular India

Advances in Zoology and Botany 8(4): 326-333, 2020 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/azb.2020.080404 Taxonomic Update and Habitat Status to Byttneria herbacea from Peninsular India Subhash R. Somkuwar Department of Botany, Dr. Ambedkar College, Deekshabhoomi Nagpur (M.S.), India Received March 31, 2020; Revised April 29, 2020; Accepted May 27, 2020 Copyright©2020 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract Byttneria herbacea is a threatened and Byttner (1724-1768), a physician and botanist at the endemic species to Indian Peninsular region. It was earlier University of Gottingen, Germany [1]. Byttneria Roxb. placed in Sterculiaceae and then a separate family was first placed in Sterculiaceae, then a separate family Byttneriaceae. As per APG classification, it is now treated Byttneriaceae. As per Angiosperm Phylogeny in family Malvaceae. Endemic taxa are usually more Group-APG-IV [2] classification Byttneria is now vulnerable to anthropogenic threats, natural and climate included in the family Malvaceae of Malvales clade. The changes, and therefore hold a higher extinction risk. Malvales clade also includes Malvaceae, Tiliaceae, Taxonomic study on endemic taxa improves a basic Bombacaceae, Bixaceae, Cistaceae, Cochlospermaceae, understanding for correct identification and description. Diegodendraceae, Dipterocarpaceae, Mutingiaceae, Habitat and distribution study are essential to get specific Neuradaceae, Sarcolaenaceae and Thymelaeaceae [2-4]. information and interpretation on current status and Finding of Judd and Manchester [5], Alverson, et al., [6] population dynamics of the taxon including niche and Bayer, et al., [4] has led to the proposal to combine requirements. -

An All-Taxa Biodiversity Inventory of the Huron Mountain Club

AN ALL-TAXA BIODIVERSITY INVENTORY OF THE HURON MOUNTAIN CLUB Version: August 2016 Cite as: Woods, K.D. (Compiler). 2016. An all-taxa biodiversity inventory of the Huron Mountain Club. Version August 2016. Occasional papers of the Huron Mountain Wildlife Foundation, No. 5. [http://www.hmwf.org/species_list.php] Introduction and general compilation by: Kerry D. Woods Natural Sciences Bennington College Bennington VT 05201 Kingdom Fungi compiled by: Dana L. Richter School of Forest Resources and Environmental Science Michigan Technological University Houghton, MI 49931 DEDICATION This project is dedicated to Dr. William R. Manierre, who is responsible, directly and indirectly, for documenting a large proportion of the taxa listed here. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 5 SOURCES 7 DOMAIN BACTERIA 11 KINGDOM MONERA 11 DOMAIN EUCARYA 13 KINGDOM EUGLENOZOA 13 KINGDOM RHODOPHYTA 13 KINGDOM DINOFLAGELLATA 14 KINGDOM XANTHOPHYTA 15 KINGDOM CHRYSOPHYTA 15 KINGDOM CHROMISTA 16 KINGDOM VIRIDAEPLANTAE 17 Phylum CHLOROPHYTA 18 Phylum BRYOPHYTA 20 Phylum MARCHANTIOPHYTA 27 Phylum ANTHOCEROTOPHYTA 29 Phylum LYCOPODIOPHYTA 30 Phylum EQUISETOPHYTA 31 Phylum POLYPODIOPHYTA 31 Phylum PINOPHYTA 32 Phylum MAGNOLIOPHYTA 32 Class Magnoliopsida 32 Class Liliopsida 44 KINGDOM FUNGI 50 Phylum DEUTEROMYCOTA 50 Phylum CHYTRIDIOMYCOTA 51 Phylum ZYGOMYCOTA 52 Phylum ASCOMYCOTA 52 Phylum BASIDIOMYCOTA 53 LICHENS 68 KINGDOM ANIMALIA 75 Phylum ANNELIDA 76 Phylum MOLLUSCA 77 Phylum ARTHROPODA 79 Class Insecta 80 Order Ephemeroptera 81 Order Odonata 83 Order Orthoptera 85 Order Coleoptera 88 Order Hymenoptera 96 Class Arachnida 110 Phylum CHORDATA 111 Class Actinopterygii 112 Class Amphibia 114 Class Reptilia 115 Class Aves 115 Class Mammalia 121 INTRODUCTION No complete species inventory exists for any area. -

General View of Malvaceae Juss. S.L. and Taxonomic Revision of Genus Abutilon Mill

JKAU: Sci., Vol. 21 No. 2, pp: 349-363 (2009 A.D. / 1430 A.H.); DOI: 10.4197 / Sci. 21-2.12 General View of Malvaceae Juss. S.L. and Taxonomic Revision of Genus Abutilon Mill. in Saudi Arabia Wafaa Kamal Taia Alexandria University, Faculty of Science, Botany Department, Alexandria, Egypt [email protected] Abstract. This works deals with the recent opinions about the new classification of the core Malvales with special reference to the family Malvaceae s.l. and the morphological description and variations in the species of the genus Abutilon Mill. Taxonomical features of the family as shown in the recent classification systems, with full description of the main divisions of the family. Position of Malvaceae s.l. in the different modern taxonomical systems is clarified. General features of the genus Abutilon stated according to the careful examination of the specimens. Taxonomic position of Abutilon in the Malvaceae is given. Artificial key based on vegetative morphological characters is provided. Keywords: Abutilon, Core Malvales, Eumalvaceae, Morpholog, Systematic Position, Taxonomy. General Features of Family Malvaceae According to Heywood[1] and Watson and Dallwitz[2] the plants of the family Malvaceae s.s. are herbs, shrubs or trees with stipulate, simple, non-sheathing alternate or spiral, petiolate leaves usually with palmate vennation (often three principal veins arising from the base of the leaf blade). Plants are hermaphrodite, rarely dioecious or poly-gamo- monoecious with floral nectarines and entomophilous pollination. Flowers are solitary or aggregating in compound cymes, varying in size from small to large, regular or somewhat irregular, cyclic with distinct calyx and corolla. -

Seney National Wildlife Refuge • Common Name(Order

Seney National Wildlife Refuge Flora • Common Name(Order Family Genus species) Monocotyledons • Arum, Green Arrow (Arales Araceae Peltranda virginica) • Arethusa (Orchidales Orchidaceae Arethusa bulbosa) • Arrowhead, Grassy (Alismatales Alismataceae Sagittaria graminea) • Bentgrass, Redtop (Poales Poaceae/Graminae Agrostis gigantea) • Bluegrass, Fowl (Poales Poaceae/Graminae Poa palustris) • Bluegrass, Kentucky (Poales Poaceae/Graminae Poa pratensis) • Brome, Smooth (Poales Poaceae/Graminae Bromus inermis) • Bulrush, Hardstem (Cyperales Cyperaceae Scirpus acutus) • Bulrush, Three-square (Cyperales Cyperaceae Scirpus americanus) • Bur-reed, Common (Typhales Sparganiaceae Sparganium eurycarpum) • Bur-reed, Eastern (Typhales Sparganiaceae Sparganium americanum) • Bur-reed, Floating (Typhales Sparganiaceae Sparganium angustifolium) • Bur-reed, Floating-leaf (Typhales Sparganiaceae Sparganium fluctuans) • Bur-reed, Least (Typhales Sparganiaceae Sparganium minimum) • Canarygrass, Reed (Poales Poaceae/Graminae Phalaris arundinaceae) • Cattail, Common (Typhales Typaceae Typha latifolia) • Cattail, Common Hybrid (Typhales Typaceae Typha x glauca) • Cattail, Narrow-leaved (Typhales Typaceae Typha angustifolia) • Celery, Wild (Hydrocharitales Hydrocharitaceae Vallisneria americana) • Chives (Liliales Liliaceae Allium schoenoprasum) • Coral-root, Spotted (Orchidales Orchidaceae Corallorhiza maculata) • Cordgrass (Poales Poaceae/Graminae Spartina pectinata) • Cottongrass, Tall (Cyperales Cyperaceae Eriophorum angustifolium) • Cottongrass, Tawny (Cyperales -

2 ANGIOSPERM PHYLOGENY GROUP (APG) SYSTEM History Of

ANGIOSPERM PHYLOGENY GROUP (APG) SYSTEM The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group, or APG, refers to an informal international group of systematic botanists who came together to try to establish a consensus view of the taxonomy of flowering plants (angiosperms) that would reflect new knowledge about their relationships based upon phylogenetic studies. As of 2010, three incremental versions of a classification system have resulted from this collaboration (published in 1998, 2003 and 2009). An important motivation for the group was what they viewed as deficiencies in prior angiosperm classifications, which were not based on monophyletic groups (i.e. groups consisting of all the descendants of a common ancestor). APG publications are increasingly influential, with a number of major herbaria changing the arrangement of their collections to match the latest APG system. Angiosperm classification and the APG Until detailed genetic evidence became available, the classification of flowering plants (also known as angiosperms, Angiospermae, Anthophyta or Magnoliophyta) was based on their morphology (particularly that of the flower) and their biochemistry (what kinds of chemical compound they contained or produced). Classification systems were typically produced by an individual botanist or by a small group. The result was a large number of such systems (see List of systems of plant taxonomy). Different systems and their updates tended to be favoured in different countries; e.g. the Engler system in continental Europe; the Bentham & Hooker system in Britain (particularly influential because it was used by Kew); the Takhtajan system in the former Soviet Union and countries within its sphere of influence; and the Cronquist system in the United States.