Draft of Privatizing Colonization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Exchange of Body Parts in the Pequot War

meanes to "A knitt them togeather": The Exchange of Body Parts in the Pequot War Andrew Lipman was IN the early seventeenth century, when New England still very new, Indians and colonists exchanged many things: furs, beads, pots, cloth, scalps, hands, and heads. The first exchanges of body parts a came during the 1637 Pequot War, punitive campaign fought by English colonists and their native allies against the Pequot people. the war and other native Throughout Mohegans, Narragansetts, peoples one gave parts of slain Pequots to their English partners. At point deliv so eries of trophies were frequent that colonists stopped keeping track of to individual parts, referring instead the "still many Pequods' heads and Most accounts of the war hands" that "came almost daily." secondary as only mention trophies in passing, seeing them just another grisly were aspect of this notoriously violent conflict.1 But these incidents a in at the Andrew Lipman is graduate student the History Department were at a University of Pennsylvania. Earlier versions of this article presented graduate student conference at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies in October 2005 and the annual conference of the South Central Society for Eighteenth-Century comments Studies in February 2006. For their and encouragement, the author thanks James H. Merrell, David Murray, Daniel K. Richter, Peter Silver, Robert Blair St. sets George, and Michael Zuckerman, along with both of conference participants and two the anonymous readers for the William and Mary Quarterly. 1 to John Winthrop, The History ofNew England from 1630 1649, ed. James 1: Savage (1825; repr., New York, 1972), 237 ("still many Pequods' heads"); John Mason, A Brief History of the Pequot War: Especially Of the memorable Taking of their Fort atMistick in Connecticut In 1637 (Boston, 1736), 17 ("came almost daily"). -

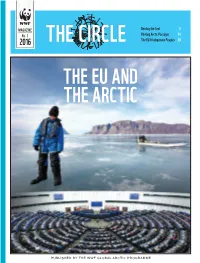

The Eu and the Arctic

MAGAZINE Dealing the Seal 8 No. 1 Piloting Arctic Passages 14 2016 THE CIRCLE The EU & Indigenous Peoples 20 THE EU AND THE ARCTIC PUBLISHED BY THE WWF GLOBAL ARCTIC PROGRAMME TheCircle0116.indd 1 25.02.2016 10.53 THE CIRCLE 1.2016 THE EU AND THE ARCTIC Contents EDITORIAL Leaving a legacy 3 IN BRIEF 4 ALYSON BAILES What does the EU want, what can it offer? 6 DIANA WALLIS Dealing the seal 8 ROBIN TEVERSON ‘High time’ EU gets observer status: UK 10 ADAM STEPIEN A call for a two-tier EU policy 12 MARIA DELIGIANNI Piloting the Arctic Passages 14 TIMO KOIVUROVA Finland: wearing two hats 16 Greenland – walking the middle path 18 FERNANDO GARCES DE LOS FAYOS The European Parliament & EU Arctic policy 19 CHRISTINA HENRIKSEN The EU and Arctic Indigenous peoples 20 NICOLE BIEBOW A driving force: The EU & polar research 22 THE PICTURE 24 The Circle is published quar- Publisher: Editor in Chief: Clive Tesar, COVER: terly by the WWF Global Arctic WWF Global Arctic Programme [email protected] (Top:) Local on sea ice in Uumman- Programme. Reproduction and 8th floor, 275 Slater St., Ottawa, naq, Greenland. quotation with appropriate credit ON, Canada K1P 5H9. Managing Editor: Becky Rynor, Photo: Lawrence Hislop, www.grida.no are encouraged. Articles by non- Tel: +1 613-232-8706 [email protected] (Bottom:) European Parliament, affiliated sources do not neces- Fax: +1 613-232-4181 Strasbourg, France. sarily reflect the views or policies Design and production: Photo: Diliff, Wikimedia Commonss of WWF. Send change of address Internet: www.panda.org/arctic Film & Form/Ketill Berger, and subscription queries to the [email protected] ABOVE: Sarek glacier, Sarek National address on the right. -

William Bradford Makes His First Substantial

Ed The Pequot Conspirator White William Bradford makes his first substantial ref- erence to the Pequots in his account of the 1628 Plymouth Plantation, in which he discusses the flourishing of the “wampumpeag” (wam- pum) trade: [S]trange it was to see the great alteration it made in a few years among the Indians themselves; for all the Indians of these parts and the Massachusetts had none or very little of it, but the sachems and some special persons that wore a little of it for ornament. Only it was made and kept among the Narragansetts and Pequots, which grew rich and potent by it, and these people were poor and beggarly and had no use of it. Neither did the English of this Plantation or any other in the land, till now that they had knowledge of it from the Dutch, so much as know what it was, much less that it was a com- modity of that worth and value.1 Reading these words, it might seem that Bradford’s understanding of Native Americans has broadened since his earlier accounts of “bar- barians . readier to fill their sides full of arrows than otherwise.”2 Could his 1620 view of them as undifferentiated, arrow-hurtling sav- ages have been superseded by one that allowed for the economically complex diversity of commodity-producing traders? If we take Brad- ford at his word, the answer is no. For “Indians”—the “poor and beg- garly” creatures Bradford has consistently described—remain present in this description but are now joined by a different type of being who have been granted proper names, are “rich and potent” compared to “Indians,” and are perhaps superior to the English in mastering the American Literature, Volume 81, Number 3, September 2009 DOI 10.1215/00029831-2009-022 © 2009 by Duke University Press Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/american-literature/article-pdf/81/3/439/392273/AL081-03-01WhiteFpp.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 440 American Literature economic lay of the land. -

Belgian Identity Politics: at a Crossroad Between Nationalism and Regionalism

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2014 Belgian identity politics: At a crossroad between nationalism and regionalism Jose Manuel Izquierdo University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Human Geography Commons Recommended Citation Izquierdo, Jose Manuel, "Belgian identity politics: At a crossroad between nationalism and regionalism. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2014. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2871 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Jose Manuel Izquierdo entitled "Belgian identity politics: At a crossroad between nationalism and regionalism." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Geography. Micheline van Riemsdijk, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Derek H. Alderman, Monica Black Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Belgian identity politics: At a crossroad between nationalism and regionalism A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Jose Manuel Izquierdo August 2014 Copyright © 2014 by Jose Manuel Izquierdo All rights reserved. -

1 Unmasking the Fake Belgians. Other Representation of Flemish And

Unmasking the Fake Belgians. Other Representation of Flemish and Walloon Elites between 1840 and 1860 Dave Sinardet & Vincent Scheltiens University of Antwerp / Free University of Brussels Paper prepared for 'Belgium: The State of the Federation' Louvain-La-Neuve, 17/10/2013 First draft All comments more than welcome! 1 Abstract In the Belgian political debate, regional and national identities are often presented as opposites, particularly by sub-state nationalist actors. Especially Flemish nationalists consider the Belgian state as artificial and obsolete and clearly support Flemish nation-building as a project directed against a Belgian federalist project. Walloon or francophone nationalism has not been very strong in recent years, but in the past Walloon regionalism has also directed itself against the Belgian state, amongst other things accused of aggravating Walloon economic decline. Despite this deep-seated antagonism between Belgian and Flemish/Walloon nation-building projects its roots are much shorter than most observers believe. Belgium’s artificial character – the grand narrative and underpinning legitimation of both substate nationalisms - has been vehemently contested in the past, not only by the French-speaking elites but especially by the Flemish movement in the period that it started up the construction of its national identity. Basing ourselves methodologically on the assumption that the construction of collective and national identities is as much a result of positive self-representation (identification) as of negative other- representation (alterification), moreover two ideas that are conceptually indissolubly related, we compare in this interdisciplinary contribution the mutual other representations of the Flemish and Walloon movements in mid-nineteenth century Belgium, when the Flemish-Walloon antagonism appeared on the surface. -

Development and Achievements of Dutch Northern and Arctic Cartography

ARCTIC’ VOL. 37, NO. 4 (DECEMBER 1984) P. 493.514 Development and Achievements of Dutch Northern and Arctic Cartography. in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth :Centuries GUNTER. SCHILDER* ther north, as far as the Shetlands the Faroes, in line with INTRODUCTION and the expansion of the Dutch .fishing and trading areas. The During the sixteenth and .seventeenth. centuries, the Dutch Thresmr contains a number of coastal viewsfrom the voyage made. a vital contribution to. the mapphg of the northern and around the North Capeas far as ‘‘Wardhuys”. Although there arctic regions, and their caPtographic work piayed a decisive is no mapofthis region, there is.a map of the coasts of Karelia part in expanding. the ,geographical .knowledgeof that time. and Russia to the east of the White Sea asfar as the Pechora, Amsterdam became the centre.of international map production accompanied by a text with instructionsfor navigation as far as and the map trade. Its Cartographers and publishers acquired Vaygach and Novaya Zemlya (Waghenaer, 1592:fo101-105). their knowledge partly from the results of expeditions fitted A coastal view.of the latter is also given.s The fact that Wag- out by theirfellow countrymen and, partlyfrom foreign henaer had access to original sources is shown by the inclusion voyages of discovery. This paper will describe the growing- in the Thresoor of the only known accountof Olivier Brunel’s Dutch..awarenessof .the northern and arctic regions. stage by voyage to-NovayaZemlya in 1584 (Waghenaer, ‘1592:P104).6 stage and region by region, with the aid of Dutch. maps. Anotherimportant document is WillemBiuentsz’s map of northern Scandinavia, which extends as faras the entrance to THE PROGRESS OF DUTCH KNOWLEDGE IN THE NORTH .the White Sea, and shows.al1 the reefs and shallows(Fig. -

Download PDF Van Tekst

Bij noorden om Olivier Brunel en de doorvaart naar China en Cathay in de zestiende eeuw Marijke Spies bron Marijke Spies, Bij noorden om. Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 1994 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/spie010bijn01_01/colofon.htm © 2006 dbnl / Marijke Spies *1 Op deze compositiekaart staat aangegeven hoe de noordelijke wereld er volgens de zestiende-eeuwse opvattingen ongeveer uitzag en waar de verschillende plaatsen en rivieren waarvan in Bij noorden om sprake is, werden gesitueerd. In grijze lijnen is onze huidige geografische kennis weergegeven. Op de uitsnede van de zee tussen Noord-Amerika en Scandinavië (links) staan de vele imaginaire eilanden die men daar situeerde. Op de ander uitsnede (rechts) is het gebied tussen de Noordkaap en de Karische Zee, waarlangs de Engelsen en Nederlanders een doortocht zochten, in detail afgebeeld. Marijke Spies, Bij noorden om V But it were to be wished, that none would write Histories with so great a desire of setting foorth novelties and strange things, [...] Arngrimus Ionas Islandus 1592 1 1 Hakluyt 1 1598, p. 561. Marijke Spies, Bij noorden om 1 I De man Zijn naam duikt op uit het niets, verdwijnt, duikt weer op. Vier, vijf vermeldingen, soms met tientallen jaren ertussen, suggereren een levensgeschiedenis die als een rode draad door de noordelijke landen van Europa loopt. Van handelsnederzetting naar koopstad en van haven weer naar handelsnederzetting: een handvol hutten aan de monding van een rivier, gehuchten waarvan de naam sinds lang gewijzigd is of vergeten. Zoveel weten we, dat ergens in het midden van de zestiende eeuw Olivier Brunel, afkomstig uit Brussel of uit Leuven, vanuit Kola aan de noordkust van Lapland naar Kholmogory aan de benedenloop van de Dwina werd gezonden om Russisch te leren.1 Gezonden door wie? Er werd in die tijd nog nauwelijks rond de Noordkaap gevaren (zie afb. -

TIDSLINJE FÖR WESTERNS UTVECKLING 50 000 F.Kr 30 000 F

För att söka uppgifter, gå till programmets sökfunktion (högerklicka var som helst på sidan så kommer det upp en valtabell TIDSLINJE FÖR WESTERNS UTVECKLING där kommandot "Sök (enkel)" finns. Klicka där och det kommer upp ett litet ifyllningsfält uppe i högra hörnet. Där kan ni skriva in det ord ni söker efter och klicka sedan på någon av de triangelformade pilsymbolerna. Då söker programmet tidpunkt för senaste uppdatering 28 Juli 2020 (sök i kolumn "infört dat ") närmaste träff på det sökta ordet, vilket då markeras med ett blått fält. tidsper datum mån dag händelse länkar för mera information (rapportera ref. infört dat länkar som inte fungerar) 50 000 50000 f. Kr De allra tidigaste invandrarna korsar landbryggan där Berings Sund nu ligger och vandrar in på den Nordamerikanska http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Native_Americans_in 1 _the_United_States f.Kr kontinenten troligen redan under tidigare perioder då inlandsisen drog sig tillbaka. Kanske redan så tidigt som för 50’000 år sedan. Men det här finns inga bevis för.Under den senaste nedisningen, som pågick under tiden mellan 26’000 år sedan och fram till för 13’300 år sedan, var så stora delar av den Nordamerikanska kontinenten täckt av is, att någon mera omfattande människoinvandring knappast har kunnat ske. Den allra senaste invandringen beräknas ha skett så sent som ett par tusen år före Kristi Födelse. De sista människogrupper som då invandrade utgör de vi numera kallar Inuiter (Eskimåer). Eftersom havet då hade stigit över den tidigare landbryggan, måste denna sena invandring antingen ha skett med någon form av båt/kanot, eller så har det vintertid funnits tillräckligt med is för att människorna har kunnat ta sig över. -

Before Albany

Before Albany THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Regents of the University ROBERT M. BENNETT, Chancellor, B.A., M.S. ...................................................... Tonawanda MERRYL H. TISCH, Vice Chancellor, B.A., M.A. Ed.D. ........................................ New York SAUL B. COHEN, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. ................................................................... New Rochelle JAMES C. DAWSON, A.A., B.A., M.S., Ph.D. ....................................................... Peru ANTHONY S. BOTTAR, B.A., J.D. ......................................................................... Syracuse GERALDINE D. CHAPEY, B.A., M.A., Ed.D. ......................................................... Belle Harbor ARNOLD B. GARDNER, B.A., LL.B. ...................................................................... Buffalo HARRY PHILLIPS, 3rd, B.A., M.S.F.S. ................................................................... Hartsdale JOSEPH E. BOWMAN,JR., B.A., M.L.S., M.A., M.Ed., Ed.D. ................................ Albany JAMES R. TALLON,JR., B.A., M.A. ...................................................................... Binghamton MILTON L. COFIELD, B.S., M.B.A., Ph.D. ........................................................... Rochester ROGER B. TILLES, B.A., J.D. ............................................................................... Great Neck KAREN BROOKS HOPKINS, B.A., M.F.A. ............................................................... Brooklyn NATALIE M. GOMEZ-VELEZ, B.A., J.D. ............................................................... -

The Lion, the Rooster, and the Union: National Identity in the Belgian Clandestine Press, 1914-1918

THE LION, THE ROOSTER, AND THE UNION: NATIONAL IDENTITY IN THE BELGIAN CLANDESTINE PRESS, 1914-1918 by MATTHEW R. DUNN Submitted to the Department of History of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for departmental honors Approved by: _________________________ Dr. Andrew Denning _________________________ Dr. Nathan Wood _________________________ Dr. Erik Scott _________________________ Date Abstract Significant research has been conducted on the trials and tribulations of Belgium during the First World War. While amateur historians can often summarize the “Rape of Belgium” and cite nationalism as a cause of the war, few people are aware of the substantial contributions of the Belgian people to the war effort and their significance, especially in the historical context of Belgian nationalism. Relatively few works have been written about the underground press in Belgium during the war, and even fewer of those works are scholarly. The Belgian underground press attempted to unite the country's two major national identities, Flemings and Walloons, using the German occupation as the catalyst to do so. Belgian nationalists were able to momentarily unite the Belgian people to resist their German occupiers by publishing pro-Belgian newspapers and articles. They relied on three pillars of identity—Catholic heritage, loyalty to the Belgian Crown, and anti-German sentiment. While this expansion of Belgian identity dissipated to an extent after WWI, the efforts of the clandestine press still serve as an important framework for the development of national identity today. By examining how the clandestine press convinced members of two separate nations, Flanders and Wallonia, to re-imagine their community to the nation of Belgium, historians can analyze the successful expansion of a nation in a war-time context. -

The Dutch & Swedes on the Delaware

THE DUTCH & SWEDES ON THE DELAWARE 1609-64 BY CHRISTOPHER WARD THE DUTCH & SWEDES on the DELAWARE 1609-64 By CHRISTOPHER WARD UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS PHILADELPHIA MCMNXX COPYRIGHT 1930, BY CHRISTOPHER WARD LONDON HUMPHREY MILFORD : OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA JOHAN PRINTZ, Governor of New Sweden,1643-53 PAINTING BY N. C. WYETH TO THE MEMORY OF MY GRANDFATHERS, CHRISTOPHER L. WARD, ESQ PRESIDENT OF THE BRADFORD COUNTY (PA.) HISTORICAL SOCIETY, AND LEWIS P. BUSH, M.D., PRESIDENT OF THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF DELAWARE, THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED PREFACE The stories of the early settlements of the English in New England, of the Dutch in New York and of the English in Maryland and Virginia have been told again and again. But, between these more northern and more southern lands, there lies a great territory stretching along both shores of Delaware River and Bay, whose earliest history has been neglected. In the common estimation of the general reader, the beginnings of civilization in this middle region are credited to William Penn and his English Quakers. Yet, for nearly fifty years before Penn came, there had been white men settled along the River's shores. When he came, he found farms, towns, forts, churches, schools, courts of law already in being in his newly acquired possessions. Small credit has been given to those who laid these foundations, the Swedes and the Dutch, whom the English superseded. The names of Winthrop, Stuyvesant, Calvert and Berkeley are familiar to many. Who knows the name of Johan Printz, the Swedish governor, who for ten years pioneered in this wilderness? Yet, in picturesqueness of personality, in force of character, in administrative ability and in actual accomplishment, within the limits of the resources granted him, Printz is the fit companion of these other so widely acclaimed men. -

Determinants of Ethnic Retention As See Through Walloon Immigrants to Wisconsin by Jacqueline Lee Tinkler

Determinants of Ethnic Retention As See Through Walloon Immigrants to Wisconsin By Jacqueline Lee Tinkler Presented to the Faculty of Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2019 Copyright © by JACQUELINE LEE TINKLER All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to express my gratitude to Kenyon Zimmer who firs supported this research idea as head of my Thesis Committee. When I decided to continue my research into the Walloon immigrants and develop the topic into a Dissertation project, he again agreed to head the committee. His stimulating questions challenged me to dig deeper and also to broaden the context. I also want to thank David Narrett and Steven Reinhardt for reading the ongoing work and offering suggestions. I am also deeply indebted to the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Texas at Arlington for the financial support which enabled me to make research trips to Wisconsin. Debora Anderson archivist at the University of Wisconsin Green Bay, and her staff were an invaluable help in locating material. Janice Zmrazek, at the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction in Madison, was a great help in locating records there. And I want to give special thanks to Mary Jane Herber, archivist at the Brown County Library in Green Bay, who was a great help in my work. I made several research trips to Wisconsin and I was privileged to be able to work among the Walloons living in the settlement area.