The Exchange of Body Parts in the Pequot War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(King Philip's War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial

Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in The Great Narragansett War (King Philip’s War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Major Jason W. Warren, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin Jr., Advisor Alan Gallay, Kristen Gremillion Peter Mansoor, Geoffrey Parker Copyright by Jason W. Warren 2011 Abstract King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was one of the bloodiest per capita in American history. Although hostile native groups damaged much of New England, Connecticut emerged unscathed from the conflict. Connecticut’s role has been obscured by historians’ focus on the disasters in the other colonies as well as a misplaced emphasis on “King Philip,” a chief sachem of the Wampanoag groups. Although Philip formed the initial hostile coalition and served as an important leader, he was later overshadowed by other sachems of stronger native groups such as the Narragansetts. Viewing the conflict through the lens of a ‘Great Narragansett War’ brings Connecticut’s role more clearly into focus, and indeed enables a more accurate narrative for the conflict. Connecticut achieved success where other colonies failed by establishing a policy of moderation towards the native groups living within its borders. This relationship set the stage for successful military operations. Local native groups, whether allied or neutral did not assist hostile Indians, denying them the critical intelligence necessary to coordinate attacks on Connecticut towns. The English colonists convinced allied Mohegan, Pequot, and Western Niantic warriors to support their military operations, giving Connecticut forces a decisive advantage in the field. -

Learning from Foxwoods Visualizing the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation

Learning from Foxwoods Visualizing the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation bill anthes Since the passage in 1988 of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, which recognized the authority of Native American tribal groups to operate gaming facilities free from state and federal oversight and taxation, gam- bling has emerged as a major industry in Indian Country. Casinos offer poverty-stricken reservation communities confined to meager slices of marginal land unprecedented economic self-sufficiency and political power.1 As of 2004, 226 of 562 federally recognized tribal groups were in the gaming business, generating a total of $16.7 billion in gross annual revenues.2 During the past two decades the proceeds from tribally owned bingo halls, casinos, and the ancillary infrastructure of a new, reserva- tion-based tourist industry have underwritten educational programs, language and cultural revitalization, social services, and not a few suc- cessful Native land claims. However, while these have been boom years in many ways for some Native groups, these same two decades have also seen, on a global scale, the obliteration of trade and political barriers and the creation of frictionless markets and a geographically dispersed labor force, as the flattening forces of the marketplace have steadily eroded the authority of the nation as traditionally conceived. As many recent commentators have noted, deterritorialization and disorganization are endemic to late capitalism.3 These conditions have implications for Native cultures. Plains Cree artist, critic, and curator Gerald McMaster has asked, “As aboriginal people struggle to reclaim land and to hold onto their present land, do their cultural identities remain stable? When aboriginal government becomes a reality, how will the local cultural identities act as centers for nomadic subjects?”4 Foxwoods Casino, a vast and highly profitable gam- ing, resort, and entertainment complex on the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation in southwestern Connecticut, might serve as a test case for McMaster’s question. -

William Bradford Makes His First Substantial

Ed The Pequot Conspirator White William Bradford makes his first substantial ref- erence to the Pequots in his account of the 1628 Plymouth Plantation, in which he discusses the flourishing of the “wampumpeag” (wam- pum) trade: [S]trange it was to see the great alteration it made in a few years among the Indians themselves; for all the Indians of these parts and the Massachusetts had none or very little of it, but the sachems and some special persons that wore a little of it for ornament. Only it was made and kept among the Narragansetts and Pequots, which grew rich and potent by it, and these people were poor and beggarly and had no use of it. Neither did the English of this Plantation or any other in the land, till now that they had knowledge of it from the Dutch, so much as know what it was, much less that it was a com- modity of that worth and value.1 Reading these words, it might seem that Bradford’s understanding of Native Americans has broadened since his earlier accounts of “bar- barians . readier to fill their sides full of arrows than otherwise.”2 Could his 1620 view of them as undifferentiated, arrow-hurtling sav- ages have been superseded by one that allowed for the economically complex diversity of commodity-producing traders? If we take Brad- ford at his word, the answer is no. For “Indians”—the “poor and beg- garly” creatures Bradford has consistently described—remain present in this description but are now joined by a different type of being who have been granted proper names, are “rich and potent” compared to “Indians,” and are perhaps superior to the English in mastering the American Literature, Volume 81, Number 3, September 2009 DOI 10.1215/00029831-2009-022 © 2009 by Duke University Press Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/american-literature/article-pdf/81/3/439/392273/AL081-03-01WhiteFpp.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 440 American Literature economic lay of the land. -

The Wawaloam Monument

A Rock of Remembrance Rhode Island Historical Cemetery EX056, also known as the “Indian Rock Cemetery,” isn’t really a cemetery at all. There are no burials at the site, only a large engraved boulder in memory of Wawaloam and her husband Miantinomi, Narragansett Indians. Sidney S. Rider, the Rhode Island bookseller and historian, collates most of the information known about Wawaloam. She was the daughter of Sequasson, a sachem living near a Connecticut river and an ally of Miantinomi. That would mean she was of the Nipmuc tribe whose territorial lands lay to the northwest of Narragansett lands. Two other bits of information suggest her origin. First, her name contains an L, a letter not found in the Narragansett language. Second, there is a location in formerly Nipmuc territory and presently the town of Glocester, Rhode Island that was called Wawalona by the Indians. The meaning of her name is uncertain, but Rider cites a “scholar learned in defining the meaning of Indian words” who speculates that it derives from the words Wa-wa (meaning “round about”) and aloam (meaning “he flies’). Together they are thought to describe the flight of a swallow as it flies over the fields. The dates of Wawaloam’s birth and death are unknown. History records that in 1632 she and Miantinomi traveled to Boston and visited Governor John Winthrop of the Massachusetts Colony at his house (Winthrop’s History of New England, vol. 1). The last thing known of her is an affidavit she signed in June 1661 at her village of Aspanansuck (Exeter Hill on the Ten Rod Road). -

Jamestown, Rhode Island

Historic andArchitectural Resources ofJamestown, Rhode Island 1 Li *fl U fl It - .-*-,. -.- - - . ---... -S - Historic and Architectural Resources of Jamestown, Rhode Island Rhode Island Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission 1995 Historic and Architectural Resources ofJamestown, Rhode Island, is published by the Rhode Island Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission, which is the state historic preservation office, in cooperation with the Jamestown Historical Society. Preparation of this publication has been funded in part by the National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. The contents and opinions herein, however, do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior. The Rhode Island Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission receives federal funds from the National Park Service. Regulations of the United States Department of the Interior strictly prohibit discrimination in departmental federally assisted programs on the basis of race, color, national origin, or handicap. Any person who believes that he or she has been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility operated by a recipient of federal assistance should write to: Director, Equal Opportunity Program, United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, P.O. Box 37127, Washington, D.C. 20013-7127. Cover East Fern’. Photograph c. 1890. Couriecy of Janiestown Historical Society. This view, looking north along tile shore, shows the steam feriy Conanicut leaving tile slip. From left to rig/It are tile Thorndike Hotel, Gardner house, Riverside, Bay View Hotel and tile Bay Voyage Inn. Only tile Bay Voyage Iiii suivives. Title Page: Beavertail Lighthouse, 1856, Beavertail Road. Tile light/louse tower at the southern tip of the island, the tallest offive buildings at this site, is a 52-foot-high stone structure. -

Massasoit of The

OUSAMEQUIN “YELLOW FEATHER” — THE MASSASOIT OF THE 1 WAMPANOAG (THOSE OF THE DAWN) “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY 1. Massasoit is not a personal name but a title, translating roughly as “The Shahanshah.” Like most native American men of the period, he had a number of personal names. Among these were Ousamequin or “Yellow Feather,” and Wasamegin. He was not only the sachem of the Pokanoket of the Mount Hope peninsula of Narragansett Bay, now Bristol and nearby Warren, Rhode Island, but also the grand sachem or Massasoit of the entire Wampanoag people. The other seven Wampanoag sagamores had all made their submissions to him, so that his influence extended to all the eastern shore of Narragansett Bay, all of Cape Cod, Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard, and the Elizabeth islands. His subordinates led the peoples of what is now Middleboro (the Nemasket), the peoples of what is now Tiverton (the Pocasset), and the peoples of what is now Little Compton (the Sakonnet). The other side of the Narragansett Bay was controlled by Narragansett sachems. HDT WHAT? INDEX THE MASSASOIT OUSAMEQUIN “YELLOW FEATHER” 1565 It would have been at about this point that Canonicus would have been born, the 1st son of the union of the son and daughter of the Narragansett headman Tashtassuck. Such a birth in that culture was considered auspicious, so we may anticipate that this infant will grow up to be a Very Important Person. Canonicus’s principle place of residence was on an island near the present Cocumcussoc of Jamestown and Wickford, Rhode Island. -

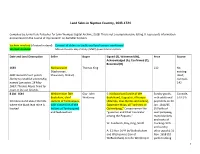

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country.Pdf

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country, 1643-1724 Compiled by Jenny Hale Pulsipher for John Wompas Digital Archive, 2018. This is not a comprehensive listing. It represents information encountered in the course of my research on Swindler Sachem. Sachem involved (if noted in deed) Consent of elders or traditional land owners mentioned Woman involved Massachusetts Bay Colony (MBC) government actions Date and Land Description Seller Buyer Signed (S), Witnessed (W), Price Source Acknowledged (A), ConFirmed (C), Recorded (R) 1643 Nashacowam Thomas King £12 No [Nashoonan, existing MBC General Court grants Shawanon, Sholan] deed; liberty to establish a township, Connole, named Lancaster, 18 May 142 1653; Thomas Noyes hired by town to lay out bounds. 8 Oct. 1644 Webomscom [We Gov. John S: Nodowahunt [uncle of We Sundry goods, Connole, Bucksham, chief Winthrop Bucksham], Itaguatiis, Alhumpis with additional 143-145 10 miles round about the hills sachem of Tantiusques, [Allumps, alias Hyems and James], payments on 20 where the black lead mine is with consent of all the Sagamore Moas, all “sachems of Jan. 1644/45 located Indians at Tantiusques] Quinnebaug,” Cassacinamon the (10 belts of and Nodowahunt “governor and Chief Councelor wampampeeg, among the Pequots.” many blankets and coats of W: Sundanch, Day, King, Smith trucking cloth and sundry A: 11 Nov. 1644 by WeBucksham other goods); 16 and Washcomos (son of Nov. 1658 (10 WeBucksham) to John Winthrop Jr. yards trucking 1 cloth); 1 March C: 20 Jan. 1644/45 by Washcomos 1658/59 to Amos Richardson, agent for John Winthrop Jr. (JWJr); 16 Nov. 1658 by Washcomos to JWJr.; 1 March 1658/59 by Washcomos to JWJr 22 May 1650 Connole, 149; MD, MBC General Court grants 7:194- 3200 acres in the vicinity of 195; MCR, LaKe Quinsigamond to Thomas 4:2:111- Dudley, esq of Boston and 112 Increase Nowell of Charleston [see 6 May and 28 July 1657, 18 April 1664, 9 June 1665]. -

TIDSLINJE FÖR WESTERNS UTVECKLING 50 000 F.Kr 30 000 F

För att söka uppgifter, gå till programmets sökfunktion (högerklicka var som helst på sidan så kommer det upp en valtabell TIDSLINJE FÖR WESTERNS UTVECKLING där kommandot "Sök (enkel)" finns. Klicka där och det kommer upp ett litet ifyllningsfält uppe i högra hörnet. Där kan ni skriva in det ord ni söker efter och klicka sedan på någon av de triangelformade pilsymbolerna. Då söker programmet tidpunkt för senaste uppdatering 28 Juli 2020 (sök i kolumn "infört dat ") närmaste träff på det sökta ordet, vilket då markeras med ett blått fält. tidsper datum mån dag händelse länkar för mera information (rapportera ref. infört dat länkar som inte fungerar) 50 000 50000 f. Kr De allra tidigaste invandrarna korsar landbryggan där Berings Sund nu ligger och vandrar in på den Nordamerikanska http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Native_Americans_in 1 _the_United_States f.Kr kontinenten troligen redan under tidigare perioder då inlandsisen drog sig tillbaka. Kanske redan så tidigt som för 50’000 år sedan. Men det här finns inga bevis för.Under den senaste nedisningen, som pågick under tiden mellan 26’000 år sedan och fram till för 13’300 år sedan, var så stora delar av den Nordamerikanska kontinenten täckt av is, att någon mera omfattande människoinvandring knappast har kunnat ske. Den allra senaste invandringen beräknas ha skett så sent som ett par tusen år före Kristi Födelse. De sista människogrupper som då invandrade utgör de vi numera kallar Inuiter (Eskimåer). Eftersom havet då hade stigit över den tidigare landbryggan, måste denna sena invandring antingen ha skett med någon form av båt/kanot, eller så har det vintertid funnits tillräckligt med is för att människorna har kunnat ta sig över. -

Vital Allies: the Colonial Militia's Use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2011 Vital allies: The colonial militia's use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676 Shawn Eric Pirelli University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Pirelli, Shawn Eric, "Vital allies: The colonial militia's use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676" (2011). Master's Theses and Capstones. 146. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/146 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VITAL ALLIES: THE COLONIAL MILITIA'S USE OF iNDIANS IN KING PHILIP'S WAR, 1675-1676 By Shawn Eric Pirelli BA, University of Massachusetts, Boston, 2008 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In History May, 2011 UMI Number: 1498967 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 1498967 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. -

The Great Swamp Fight in Fairfield

THE GREAT SWAMP FIGHT IN FAIRFIELD A PAPER PREPARED FOR AND READ AT A MEETING OF THE COLONIAL DAMES BY HON. JOHN H. PERRY ON OCTOBER TWELFTH, NINETEEN HUNDRED AND FIVE NEW YORK 1905 1 mmVi SPiiii ii • X \ THE GREAT SWAMP FIGHT IN FAIRFIELD A PAPER PREPARED FOR AND READ AT A MEETING OF THE COLONIAL DAMES BY HON. JOHN H. PERRY ON OCTOBER TWELFTH, NINETEEN HUNDRED AND FIVE NEW YORK 1905 THE GREAT SWAMP FIGHT IN FAIRFIELD HON. JOHN H. PERRY You are met this afternoon in a town conspicuously honorable and honored even in the Connecticut galaxy. I am not its historian nor its panegyrist. It has notable incumbents of both offices, who should be in my place to-day. While I once professed to right wrongs, I never pretended to write stories, and my present predicament is the evolved outcome of a long line of pious ancestry, my fitness to survive which is demonstrated by a genius for obedience. When I was bidden to read a paper to you I found my ability to disobey atrophied by long disuse. I can tender nothing worthy of the town or the occasion, and I frankly throw myself for mercy upon that peace- with-all-the-world feeling which invariably follows the hospitality of Osborn Hill. To have steadily produced Jenningses and Goulds and Burrs generation after generation would alone pay the debt of any town to its country; but Fairfield, insatiable in usefulness, has not been content with that. She has produced college founders and Yale presidents, great preachers, United States senators and representa- tives, famous poets, learned judges, governors, secretaries of state, and other notables in number out of all proportions to her size. -

Alyson J. Fink

PSYCHOLOGICAL CONQUEST: PILGRIMS, INDIANS AND THE PLAGUE OF 1616-1618 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAW AI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN mSTORY MAY 2008 By Alyson J. Fink Thesis Committee: Richard C. Rath, Chairperson Marcus Daniel Margot A. Henriksen Richard L. Rapson We certify that we have read this thesis and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. THESIS COMMITIEE ~J;~e K~ • ii ABSTRACT In New England effects of the plague of 1616 to 1618 were felt by the Wampanoags, Massachusetts and Nausets on Cape Cod. On the other hand, the Narragansetts were not affiicted by the same plague. Thus they are a strong exemplar of how an Indian nation, not affected by disease and the psychological implications of it, reacted to settlement. This example, when contrasted with that of the Wampanoags and Massachusetts proves that one nation with no experience of death caused by disease reacted aggressively towards other nations and the Pilgrims, while nations fearful after the epidemic reacted amicably towards the Pilgrims. Therefore showing that the plague produced short-term rates of population decline which then caused significant psychological effects to develop and shape human interaction. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................... .iii List of Tables ...........................................................................................v -

Battle of Pequot Swamp Archaeological

Technical Report Battle of Pequot (Munnacommock) Swamp, July 13-14, 1637 Department of the Interior National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program GA-2287-15-008 Courtesy Fairfield Museum and History Center This material is based upon work assisted by a grant from the Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior. David Naumec, Ashley Bissonnette, Noah Fellman, Kevin McBride September 13, 2017 1 | GA-2287-15-008 Technical Report Contents I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................4 Project Goals and Results ................................................................................................ 5 II. Preservation & Documentation of Pequot War Battlefield Sites ..............................6 Preservation ..................................................................................................................... 6 Documentation ................................................................................................................ 6 Defining the Battlefield Boundary and Core Areas ........................................................ 8 III. Historic Context ......................................................................................................10 Contact, Trade, and Pequot Expansion in Southern New England