William Bradford Makes His First Substantial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Exchange of Body Parts in the Pequot War

meanes to "A knitt them togeather": The Exchange of Body Parts in the Pequot War Andrew Lipman was IN the early seventeenth century, when New England still very new, Indians and colonists exchanged many things: furs, beads, pots, cloth, scalps, hands, and heads. The first exchanges of body parts a came during the 1637 Pequot War, punitive campaign fought by English colonists and their native allies against the Pequot people. the war and other native Throughout Mohegans, Narragansetts, peoples one gave parts of slain Pequots to their English partners. At point deliv so eries of trophies were frequent that colonists stopped keeping track of to individual parts, referring instead the "still many Pequods' heads and Most accounts of the war hands" that "came almost daily." secondary as only mention trophies in passing, seeing them just another grisly were aspect of this notoriously violent conflict.1 But these incidents a in at the Andrew Lipman is graduate student the History Department were at a University of Pennsylvania. Earlier versions of this article presented graduate student conference at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies in October 2005 and the annual conference of the South Central Society for Eighteenth-Century comments Studies in February 2006. For their and encouragement, the author thanks James H. Merrell, David Murray, Daniel K. Richter, Peter Silver, Robert Blair St. sets George, and Michael Zuckerman, along with both of conference participants and two the anonymous readers for the William and Mary Quarterly. 1 to John Winthrop, The History ofNew England from 1630 1649, ed. James 1: Savage (1825; repr., New York, 1972), 237 ("still many Pequods' heads"); John Mason, A Brief History of the Pequot War: Especially Of the memorable Taking of their Fort atMistick in Connecticut In 1637 (Boston, 1736), 17 ("came almost daily"). -

(King Philip's War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial

Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in The Great Narragansett War (King Philip’s War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Major Jason W. Warren, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin Jr., Advisor Alan Gallay, Kristen Gremillion Peter Mansoor, Geoffrey Parker Copyright by Jason W. Warren 2011 Abstract King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was one of the bloodiest per capita in American history. Although hostile native groups damaged much of New England, Connecticut emerged unscathed from the conflict. Connecticut’s role has been obscured by historians’ focus on the disasters in the other colonies as well as a misplaced emphasis on “King Philip,” a chief sachem of the Wampanoag groups. Although Philip formed the initial hostile coalition and served as an important leader, he was later overshadowed by other sachems of stronger native groups such as the Narragansetts. Viewing the conflict through the lens of a ‘Great Narragansett War’ brings Connecticut’s role more clearly into focus, and indeed enables a more accurate narrative for the conflict. Connecticut achieved success where other colonies failed by establishing a policy of moderation towards the native groups living within its borders. This relationship set the stage for successful military operations. Local native groups, whether allied or neutral did not assist hostile Indians, denying them the critical intelligence necessary to coordinate attacks on Connecticut towns. The English colonists convinced allied Mohegan, Pequot, and Western Niantic warriors to support their military operations, giving Connecticut forces a decisive advantage in the field. -

Learning from Foxwoods Visualizing the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation

Learning from Foxwoods Visualizing the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation bill anthes Since the passage in 1988 of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, which recognized the authority of Native American tribal groups to operate gaming facilities free from state and federal oversight and taxation, gam- bling has emerged as a major industry in Indian Country. Casinos offer poverty-stricken reservation communities confined to meager slices of marginal land unprecedented economic self-sufficiency and political power.1 As of 2004, 226 of 562 federally recognized tribal groups were in the gaming business, generating a total of $16.7 billion in gross annual revenues.2 During the past two decades the proceeds from tribally owned bingo halls, casinos, and the ancillary infrastructure of a new, reserva- tion-based tourist industry have underwritten educational programs, language and cultural revitalization, social services, and not a few suc- cessful Native land claims. However, while these have been boom years in many ways for some Native groups, these same two decades have also seen, on a global scale, the obliteration of trade and political barriers and the creation of frictionless markets and a geographically dispersed labor force, as the flattening forces of the marketplace have steadily eroded the authority of the nation as traditionally conceived. As many recent commentators have noted, deterritorialization and disorganization are endemic to late capitalism.3 These conditions have implications for Native cultures. Plains Cree artist, critic, and curator Gerald McMaster has asked, “As aboriginal people struggle to reclaim land and to hold onto their present land, do their cultural identities remain stable? When aboriginal government becomes a reality, how will the local cultural identities act as centers for nomadic subjects?”4 Foxwoods Casino, a vast and highly profitable gam- ing, resort, and entertainment complex on the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation in southwestern Connecticut, might serve as a test case for McMaster’s question. -

The Wawaloam Monument

A Rock of Remembrance Rhode Island Historical Cemetery EX056, also known as the “Indian Rock Cemetery,” isn’t really a cemetery at all. There are no burials at the site, only a large engraved boulder in memory of Wawaloam and her husband Miantinomi, Narragansett Indians. Sidney S. Rider, the Rhode Island bookseller and historian, collates most of the information known about Wawaloam. She was the daughter of Sequasson, a sachem living near a Connecticut river and an ally of Miantinomi. That would mean she was of the Nipmuc tribe whose territorial lands lay to the northwest of Narragansett lands. Two other bits of information suggest her origin. First, her name contains an L, a letter not found in the Narragansett language. Second, there is a location in formerly Nipmuc territory and presently the town of Glocester, Rhode Island that was called Wawalona by the Indians. The meaning of her name is uncertain, but Rider cites a “scholar learned in defining the meaning of Indian words” who speculates that it derives from the words Wa-wa (meaning “round about”) and aloam (meaning “he flies’). Together they are thought to describe the flight of a swallow as it flies over the fields. The dates of Wawaloam’s birth and death are unknown. History records that in 1632 she and Miantinomi traveled to Boston and visited Governor John Winthrop of the Massachusetts Colony at his house (Winthrop’s History of New England, vol. 1). The last thing known of her is an affidavit she signed in June 1661 at her village of Aspanansuck (Exeter Hill on the Ten Rod Road). -

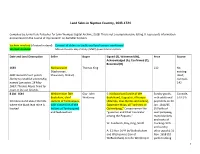

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country.Pdf

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country, 1643-1724 Compiled by Jenny Hale Pulsipher for John Wompas Digital Archive, 2018. This is not a comprehensive listing. It represents information encountered in the course of my research on Swindler Sachem. Sachem involved (if noted in deed) Consent of elders or traditional land owners mentioned Woman involved Massachusetts Bay Colony (MBC) government actions Date and Land Description Seller Buyer Signed (S), Witnessed (W), Price Source Acknowledged (A), ConFirmed (C), Recorded (R) 1643 Nashacowam Thomas King £12 No [Nashoonan, existing MBC General Court grants Shawanon, Sholan] deed; liberty to establish a township, Connole, named Lancaster, 18 May 142 1653; Thomas Noyes hired by town to lay out bounds. 8 Oct. 1644 Webomscom [We Gov. John S: Nodowahunt [uncle of We Sundry goods, Connole, Bucksham, chief Winthrop Bucksham], Itaguatiis, Alhumpis with additional 143-145 10 miles round about the hills sachem of Tantiusques, [Allumps, alias Hyems and James], payments on 20 where the black lead mine is with consent of all the Sagamore Moas, all “sachems of Jan. 1644/45 located Indians at Tantiusques] Quinnebaug,” Cassacinamon the (10 belts of and Nodowahunt “governor and Chief Councelor wampampeeg, among the Pequots.” many blankets and coats of W: Sundanch, Day, King, Smith trucking cloth and sundry A: 11 Nov. 1644 by WeBucksham other goods); 16 and Washcomos (son of Nov. 1658 (10 WeBucksham) to John Winthrop Jr. yards trucking 1 cloth); 1 March C: 20 Jan. 1644/45 by Washcomos 1658/59 to Amos Richardson, agent for John Winthrop Jr. (JWJr); 16 Nov. 1658 by Washcomos to JWJr.; 1 March 1658/59 by Washcomos to JWJr 22 May 1650 Connole, 149; MD, MBC General Court grants 7:194- 3200 acres in the vicinity of 195; MCR, LaKe Quinsigamond to Thomas 4:2:111- Dudley, esq of Boston and 112 Increase Nowell of Charleston [see 6 May and 28 July 1657, 18 April 1664, 9 June 1665]. -

TIDSLINJE FÖR WESTERNS UTVECKLING 50 000 F.Kr 30 000 F

För att söka uppgifter, gå till programmets sökfunktion (högerklicka var som helst på sidan så kommer det upp en valtabell TIDSLINJE FÖR WESTERNS UTVECKLING där kommandot "Sök (enkel)" finns. Klicka där och det kommer upp ett litet ifyllningsfält uppe i högra hörnet. Där kan ni skriva in det ord ni söker efter och klicka sedan på någon av de triangelformade pilsymbolerna. Då söker programmet tidpunkt för senaste uppdatering 28 Juli 2020 (sök i kolumn "infört dat ") närmaste träff på det sökta ordet, vilket då markeras med ett blått fält. tidsper datum mån dag händelse länkar för mera information (rapportera ref. infört dat länkar som inte fungerar) 50 000 50000 f. Kr De allra tidigaste invandrarna korsar landbryggan där Berings Sund nu ligger och vandrar in på den Nordamerikanska http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Native_Americans_in 1 _the_United_States f.Kr kontinenten troligen redan under tidigare perioder då inlandsisen drog sig tillbaka. Kanske redan så tidigt som för 50’000 år sedan. Men det här finns inga bevis för.Under den senaste nedisningen, som pågick under tiden mellan 26’000 år sedan och fram till för 13’300 år sedan, var så stora delar av den Nordamerikanska kontinenten täckt av is, att någon mera omfattande människoinvandring knappast har kunnat ske. Den allra senaste invandringen beräknas ha skett så sent som ett par tusen år före Kristi Födelse. De sista människogrupper som då invandrade utgör de vi numera kallar Inuiter (Eskimåer). Eftersom havet då hade stigit över den tidigare landbryggan, måste denna sena invandring antingen ha skett med någon form av båt/kanot, eller så har det vintertid funnits tillräckligt med is för att människorna har kunnat ta sig över. -

The Great Swamp Fight in Fairfield

THE GREAT SWAMP FIGHT IN FAIRFIELD A PAPER PREPARED FOR AND READ AT A MEETING OF THE COLONIAL DAMES BY HON. JOHN H. PERRY ON OCTOBER TWELFTH, NINETEEN HUNDRED AND FIVE NEW YORK 1905 1 mmVi SPiiii ii • X \ THE GREAT SWAMP FIGHT IN FAIRFIELD A PAPER PREPARED FOR AND READ AT A MEETING OF THE COLONIAL DAMES BY HON. JOHN H. PERRY ON OCTOBER TWELFTH, NINETEEN HUNDRED AND FIVE NEW YORK 1905 THE GREAT SWAMP FIGHT IN FAIRFIELD HON. JOHN H. PERRY You are met this afternoon in a town conspicuously honorable and honored even in the Connecticut galaxy. I am not its historian nor its panegyrist. It has notable incumbents of both offices, who should be in my place to-day. While I once professed to right wrongs, I never pretended to write stories, and my present predicament is the evolved outcome of a long line of pious ancestry, my fitness to survive which is demonstrated by a genius for obedience. When I was bidden to read a paper to you I found my ability to disobey atrophied by long disuse. I can tender nothing worthy of the town or the occasion, and I frankly throw myself for mercy upon that peace- with-all-the-world feeling which invariably follows the hospitality of Osborn Hill. To have steadily produced Jenningses and Goulds and Burrs generation after generation would alone pay the debt of any town to its country; but Fairfield, insatiable in usefulness, has not been content with that. She has produced college founders and Yale presidents, great preachers, United States senators and representa- tives, famous poets, learned judges, governors, secretaries of state, and other notables in number out of all proportions to her size. -

Battle of Pequot Swamp Archaeological

Technical Report Battle of Pequot (Munnacommock) Swamp, July 13-14, 1637 Department of the Interior National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program GA-2287-15-008 Courtesy Fairfield Museum and History Center This material is based upon work assisted by a grant from the Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior. David Naumec, Ashley Bissonnette, Noah Fellman, Kevin McBride September 13, 2017 1 | GA-2287-15-008 Technical Report Contents I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................4 Project Goals and Results ................................................................................................ 5 II. Preservation & Documentation of Pequot War Battlefield Sites ..............................6 Preservation ..................................................................................................................... 6 Documentation ................................................................................................................ 6 Defining the Battlefield Boundary and Core Areas ........................................................ 8 III. Historic Context ......................................................................................................10 Contact, Trade, and Pequot Expansion in Southern New England -

Abstract Hero, Villian, and Diplomat: an Investigation

ABSTRACT HERO, VILLIAN, AND DIPLOMAT: AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE MULTIPLE IDENTITIES OF COMMANDER JOHN MASON IN COLONIAL CONNECTICUT BY William Lee Dreger Traditionally, historians have treated the convergence of cultures between natives and Europeans in North America as a linear narrative resulting in overwhelming European dominance. While much that has been argued in favor of this stance is strongly supported by available sources, this position tends to oversimplify the dynamics of colonial interaction. Through an in-depth and focused study of Commander John Mason and his many identities in seventeenth- century colonial Connecticut this widely-accepted simplified explanation of interaction can be replaced by the more complex reality. Mason, the commander of English forces during the Pequot War, simultaneously attempted to annihilate surrounding Pequots and maintain positive relations with members of the Mohegan tribe, a group that in the previous decade had splintered from the Pequot tribe. Through both primary and secondary sources one can better understand Mason, the Pequot War, and the intricacies of colonial interaction concerning settlers and natives writ large. Hero, Villian, And Diplomat: An Investigation Into The Multiple Identities Of Commander John Mason In Colonial Connecticut A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by William Lee Dreger Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2005 Advisor ___________________ Carla L. Pestana Reader ____________________ Andrew Cayton Reader ___________________ Daniel Cobb Table of Contents I. Introduction II. Chapter 1: The Pequot War III. Chapter 2: John Mason; Hero or Indian-Hater? IV. Chapter 3: John Mason; The Mohegan Protector V. -

A War All Our Own: American Rangers and the Emergence of the American Martial Culture

A War All Our Own: American Rangers and the Emergence of the American Martial Culture by James Sandy, M.A. A Dissertation In HISTORY Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTORATE IN PHILOSOPHY Approved Dr. John R. Milam Chair of Committee Dr. Laura Calkins Dr. Barton Myers Dr. Aliza Wong Mark Sheridan, PhD. Dean of the Graduate School May, 2016 Copyright 2016, James Sandy Texas Tech University, James A. Sandy, May 2016 Acknowledgments This work would not have been possible without the constant encouragement and tutelage of my committee. They provided the inspiration for me to start this project, and guided me along the way as I slowly molded a very raw idea into the finished product here. Dr. Laura Calkins witnessed the birth of this project in my very first graduate class and has assisted me along every step of the way from raw idea to thesis to completed dissertation. Dr. Calkins has been and will continue to be invaluable mentor and friend throughout my career. Dr. Aliza Wong expanded my mind and horizons during a summer session course on Cultural Theory, which inspired a great deal of the theoretical framework of this work. As a co-chair of my committee, Dr. Barton Myers pushed both the project and myself further and harder than anyone else. The vast scope that this work encompasses proved to be my biggest challenge, but has come out as this works’ greatest strength and defining characteristic. I cannot thank Dr. Myers enough for pushing me out of my comfort zone, and for always providing the firmest yet most encouraging feedback. -

POLICY of MAINE, 1620-1820 by MARGARET FOWLES WILDE a THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree

HISTORY OF THE PUBLIC LAND POLICY OF MAINE, 1620-1820 By MARGARET FOWLES WILDE % A., University of Maine, 1932 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in History and Government) Division of Graduate Study University of Maine Orono May, 1940 ABSTRACT HISTORY OF THE PUBLIC LAND POLICY OF MAINE, 1620-1820 There have been many accounts of individual settlements in Maine and a few histories of the State, but no one has ever attempted a history of its land policy or analyzed the effect that such a policy or lack of policy might have had on the development of the State of Maine. Maine was one of the earliest sections of the Atlantic Coast 'to be explored but one of the slowest in development. The latter may have been due to a number of factors but undoubtedly the lack of a definite, well developed land policy had much to do with the slow progress of settlement and development of this area. The years 1602 to 1620 marked the beginnings of explorations along the Maine Coast principally by the English and French. In 1603, Henry IV of France granted all the American territory between the fortieth and forty-six degrees north latitude to Pierre de Gast Sieure de Monts. This territory was called Acadia. Soon after, in 1606 King James I of England granted all the lands between the thirty-fourth and forty-fifth degrees north latitude to an association of noblemen of London and Plymouth. Later, King James I of England granted all the lands from the fortieth to the forty-eighth degrees of north latitude to a company called ’’Council established at Plymouth in the County of Devon; for planting, ruling, and governing New England in America.” This company functioned from 1620-1635. -

King Philip's Ghost: Race War and Remembrance in the Nashoba Regional School

King Philip’s Ghost: Race War and Remembrance in the Nashoba Regional School District By Timothy H. Castner 1 The gruesome image still has the power to shock. A grim reminder of what Thoreau termed the Dark Age of New England. The human head was impaled upon a pole and raised high above Plymouth. The townspeople had been meeting for a solemn Thanksgiving filled with prayers and sermons, celebrating the end of the most brutal and genocidal war in American history. The arrival and raising of the skull marked a symbolic high point of the festivities. Many years later the great Puritan minister, Cotton Mather, visited the site and removed the jaw bone from the then exposed skull, symbolically silencing the voice of a person long dead and dismembered. There the skull remained for decades, perhaps as long as forty years as suggested by historian Jill Lepore. Yet while his mortal remains went the way of all flesh, Metacom or King Philip, refused to be silenced. He haunts our landscape, our memories and our self-conception. How might we choose to live or remember differently if we paused to learn and listen? For Missing Image go to http://www.telegram.com/apps/pbcsi.dll/bilde?NewTbl=1&Site=WT&Date=20130623&Category=COULTER02&Art No=623009999&Ref=PH&Item=75&Maxw=590&Maxh=450 In June of 2013 residents of Bolton and members of the Nashoba Regional School District had two opportunities to ponder the question of the Native American heritage of the area. On June 9th at the Nashoba Regional Graduation Ceremony, Bolton resident and Nashoba Valedictorian, Alex Ablavsky questioned the continued use of the Chieftain and associated imagery, claiming that it was a disrespectful appropriation of another groups iconography which tarnished his experience at Nashoba.