An Investigation Into Weston's Colony at Wessagussett Weymouth, MA Craig S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

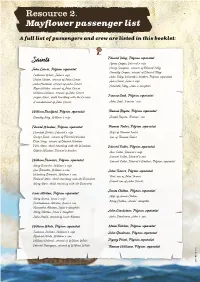

Resource 2 Mayflower Passenger List

Resource 2. Mayflower passenger list A full list of passengers and crew are listed in this booklet: Edward Tilley, Pilgrim separatist Saints Agnus Cooper, Edward’s wife John Carver, Pilgrim separatist Henry Sampson, servant of Edward Tilley Humility Cooper, servant of Edward Tilley Catherine White, John’s wife John Tilley, Edwards’s brother, Pilgrim separatist Desire Minter, servant of John Carver Joan Hurst, John’s wife John Howland, servant of John Carver Elizabeth Tilley, John’s daughter Roger Wilder, servant of John Carver William Latham, servant of John Carver Jasper More, child travelling with the Carvers Francis Cook, Pilgrim separatist A maidservant of John Carver John Cook, Francis’ son William Bradford, Pilgrim separatist Thomas Rogers, Pilgrim separatist Dorothy May, William’s wife Joseph Rogers, Thomas’ son Edward Winslow, Pilgrim separatist Thomas Tinker, Pilgrim separatist Elizabeth Barker, Edward’s wife Wife of Thomas Tinker George Soule, servant of Edward Winslow Son of Thomas Tinker Elias Story, servant of Edward Winslow Ellen More, child travelling with the Winslows Edward Fuller, Pilgrim separatist Gilbert Winslow, Edward’s brother Ann Fuller, Edward’s wife Samuel Fuller, Edward’s son William Brewster, Pilgrim separatist Samuel Fuller, Edward’s Brother, Pilgrim separatist Mary Brewster, William’s wife Love Brewster, William’s son John Turner, Pilgrim separatist Wrestling Brewster, William’s son First son of John Turner Richard More, child travelling with the Brewsters Second son of John Turner Mary More, child travelling -

Duxbury's First Settlers Were Mayflower Passengers

Duxbury’s first settlers were Mayflower passengers... “…the people of the Plantation began to grow in their outward estates…and no man thought he could live, except he had cattle and a great deal of ground to keep them, all striving to increase their stocks. By which means, they were scattered all over the bay quickly.” William Bradford, Of Plimoth Plantation. In 1627, seven years after their arrival, Myles Standish, William Bradford, Elder Brewster, John Alden and other Plymouth leaders called “Undertakers” had assumed the debt owed their investors and moved to an area ultimately incorporated in 1637 as Duxbury. As families started to leave Plymouth in the land division of 1627 each member was allotted 20 acres to create a family farm with lots starting at the water’s edge. Duxbury’s earliest economic beginnings started the American dream of land ownership. Its exports suppled corn, timber and commodities to Boston’s Winthrop migration in the 1630s. Coasters like John Alden and John How- land established coastal fur trading with Native Americans in Maine. They traded and shipped fur pelts back to England to be used for felt which was the fabric of the garment industry at that time in history. Leading up to 2020, Duxbury has joined with other regional Pilgrim related historic sites to commemorate the 400th Mayflower Journey and Plymouth Settlement. Future Duxbury was first explored from Clark’s Island. Before landing in Plymouth, the Mayflower anchored off Provincetown and a scouting party in a smaller boat set sail to explore what is now Cape Cod Bay. -

On-Site Historical Reenactment As Historiographic Operation at Plimoth Plantation

Fall2002 107 Recreation and Re-Creation: On-Site Historical Reenactment as Historiographic Operation at Plimoth Plantation Scott Magelssen Plimoth Plantation, a Massachusetts living history museum depicting the year 1627 in Plymouth Colony, advertises itself as a place where "history comes alive." The site uses costumed Pilgrims, who speak to visitors in a first-person presentvoice, in order to create a total living environment. Reenactment practices like this offer possibilities to teach history in a dynamic manner by immersing visitors in a space that allows them to suspend disbelief and encounter museum exhibits on an affective level. However, whether or not history actually "comes alive"at Plimoth Plantation needs to be addressed, especially in the face of new or postmodem historiography. No longer is it so simple to say the past can "come alive," given that in the last thirty years it has been shown that the "past" is contestable. A case in point, I argue, is the portrayal of Wampanoag Natives at Plimoth Plantation's "Hobbamock's Homesite." Here, the Native Wampanoag Interpretation Program refuses tojoin their Pilgrim counterparts in using first person interpretation, choosing instead to address visitors in their own voices. For the Native Interpreters, speaking in seventeenth-century voices would disallow presentationoftheir own accounts ofthe way colonists treated native peoples after 1627. Yet, from what I have learned in recent interviews with Plimoth's Public Relations Department, plans are underway to address the disparity in interpretive modes between the Pilgrim Village and Hobbamock's Homesite by introducing first person programming in the latter. I Coming from a theatre history and theory background, and looking back on three years of research at Plimoth and other living history museums, I would like to trouble this attempt to smooth over the differences between the two sites. -

A Genealogical Profile of Joshua Pratt

A Genealogical Profile of Joshua Pratt Birth: Joshua Pratt was born in England about 1605 based on the estimated date of marriage. Death: He died in Plymouth between June 5, 1655, and October 5, 1656. Ship: Anne or Little James,1623 Life in England: Nothing is known of his life in England. Life in New England: Joshua Pratt came over as a single man in 1623. He was a freeman of Plymouth in 1633. He served on a number of committees and juries, as well as other positions including messenger, constable and viewer of land. He has often been identified as the brother of Phineas Pratt, who came to Plymouth in 1622 but such kinship has not been proven. Family: Joshua Pratt married Bathsheba _____ by about 1630, assuming she was the mother of all his children, and had four children. She married (2) John Doggett on August 29, 1667 in Plymouth. • Benajah was born about 1630. He married Persis Dunham on November 29, 1655, in Plymouth and had eleven children. He died in Plymouth on March 17, 1682/3. • Hannah was born about 1632. She married William Spooner on March 18, 1651, in Plymouth and had eight children. • Jonathan was born about 1637. He married (1) Abigail Wood on November 2, 1664, in Plymouth and had eight children. He married (2) Elizabeth (White) Hall on March 3, 1689/90, in Taunton. • Bathsheba was born about 1639. She married Joshua Royce in Charleston in December 1662 and had at least one son. For Further Information: Robert C. Anderson. The Great Migration Begins. -

Christopher Levett, of York; the Pioneer Colonist in Casco Bay Volume 5

DSNFXAY0DLQ1 Kindle < Christopher Levett, of York; The Pioneer Colonist in Casco Bay Volume 5... Christopher Levett, of York; The Pioneer Colonist in Casco Bay Volume 5 (Paperback) Filesize: 7.52 MB Reviews Absolutely essential read through ebook. Better then never, though i am quite late in start reading this one. Your life span will likely be change once you total reading this article pdf. (Jody Veum) DISCLAIMER | DMCA EJIPMB2X6RHZ « Book » Christopher Levett, of York; The Pioneer Colonist in Casco Bay Volume 5... CHRISTOPHER LEVETT, OF YORK; THE PIONEER COLONIST IN CASCO BAY VOLUME 5 (PAPERBACK) To download Christopher Levett, of York; The Pioneer Colonist in Casco Bay Volume 5 (Paperback) eBook, make sure you refer to the web link below and save the document or gain access to additional information which might be related to CHRISTOPHER LEVETT, OF YORK; THE PIONEER COLONIST IN CASCO BAY VOLUME 5 (PAPERBACK) book. Theclassics.Us, United States, 2013. Paperback. Book Condition: New. 246 x 189 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****.This historic book may have numerous typos and missing text. Purchasers can usually download a free scanned copy of the original book (without typos) from the publisher. Not indexed. Not illustrated. 1893 edition. Excerpt: . The Maine Historical Society published in 1847 a book of thirty-four pages, bearing the attractive title of A Voyage into New England, begun in 1623 and ended in 1624, Performed by Christopher Levett, His Majesty s Woodward of Somersetshire, and one of the Council of New England, printed at London by William fones and sold by Edward Brewster, at the sign of the Bible, in Paufs Churchyard, 1628. -

Sir Ferdinando Gorges

PEOPLE MENTIONED IN CAPE COD PEOPLE MENTIONED IN CAPE COD: SIR FERDINANDO GORGES “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project The People of Cape Cod: Sir Fernando Gorges HDT WHAT? INDEX THE PEOPLE OF CAPE COD: SIR FERDINANDO GORGES PEOPLE MENTIONED IN CAPE COD CAPE COD: Even as late as 1633 we find Winthrop, the first Governor PEOPLE OF of the Massachusetts Colony, who was not the most likely to be CAPE COD misinformed, who, moreover, has the fame, at least, of having discovered Wachusett Mountain (discerned it forty miles inland), talking about the “Great Lake” and the “hideous swamps about it,” near which the Connecticut and the “Potomack” took their rise; and among the memorable events of the year 1642 he chronicles Darby Field, an Irishman’s expedition to the “White hill,” from whose top he saw eastward what he “judged to be the Gulf of Canada,” and westward what he “judged to be the great lake which Canada River comes out of,” and where he found much “Muscovy glass,” and “could rive out pieces of forty feet long and seven or eight broad.” While the very inhabitants of New England were thus fabling about the country a hundred miles inland, which was a terra incognita to them, —or rather many years before the earliest date referred to,— Champlain, the first Governor of CHAMPLAIN Canada, not to mention the inland discoveries of Cartier, CARTIER Roberval, and others, of the preceding century, and his own ROBERVAL earlier voyage, had already gone to war against the Iroquois in ALPHONSE their forest forts, and penetrated to the Great Lakes and wintered there, before a Pilgrim had heard of New England. -

Pathways of the Past: Part 1 Maurice Robbins

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Journals and Campus Publications Society 1984 Pathways of the Past: Part 1 Maurice Robbins Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/bmas Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Copyright © 1984 Massachusetts Archaeological Society This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. 1 A SERIES by "Maurice Robbins Publ ished b~' THE MASSACHUSETTS ARCHAEOLOGICAL 80CIETY~ Inc. ROBBINS MUSEUM OF ARCHAEOLOGY - P.O. BOX 700 . MIDDLEBORO. MA 02~6-0700 508-947-9005 PLIMOTH/NEMASKET PATH arllER PATllS AND TRAILS MODERN STREETS M40-61 is an archaeological site presumed to be the ancient Indian village of Nemasket. ' ....... " ... ................ \ , \ \, ,, ENLARGEMENT OF SHADED AREA "At: \• 1- " <f. \', LOUT .. NEMASKET PATH ", POND , ..,.... .: NARRAGANSETT POND " ' \ PLYt-1OUTH PATH ", "' ... \ • : '\ , \ (1'\ "\ 1J COOPER POND MEADOW POND \, \ \ I , \ \ . , ' MUDDY POND .. I "I... I \ ' \ 1J I" ~ \ \v JOHN I S POND 1/2 0 1 , \ \ \ +-----+1---+-1---f ,, \ , MILES -,-,,---. -----_... ~ .. -"--~ ............ ., ,"-"-J~~~~,----;'"~ /" ~ CllES1'Nlfr " ~7/_M40-61 ,/ WADING PLACE ,/' ~'\, / .5';. ~~, ~~;. ,,/ \},,, I " / ' , , .... -------: " ''''''-1 ...... ~,,: " . , ! /' I Copyright 1984 by Maurice Robbins MIDDLEBORO USGS QUADRANG~E PLYMPTON USGS QUADPJU~GLE PLY~~UTH USGS QUADRAJ~GLE This journal and -

New England‟S Memorial

© 2009, MayflowerHistory.com. All Rights Reserved. New England‟s Memorial: Or, A BRIEF RELATION OF THE MOST MEMORABLE AND REMARKABLE PASSAGES OF THE PROVIDENCE OF GOD, MANIFESTED TO THE PLANTERS OF NEW ENGLAND IN AMERICA: WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE FIRST COLONY THEREOF, CALLED NEW PLYMOUTH. AS ALSO A NOMINATION OF DIVERS OF THE MOST EMINENT INSTRUMENTS DECEASED, BOTH OF CHURCH AND COMMONWEALTH, IMPROVED IN THE FIRST BEGINNING AND AFTER PROGRESS OF SUNDRY OF THE RESPECTIVE JURISDICTIONS IN THOSE PARTS; IN REFERENCE UNTO SUNDRY EXEMPLARY PASSAGES OF THEIR LIVES, AND THE TIME OF THEIR DEATH. Published for the use and benefit of present and future generations, BY NATHANIEL MORTON, SECRETARY TO THE COURT, FOR THE JURISDICTION OF NEW PLYMOUTH. Deut. xxxii. 10.—He found him in a desert land, in the waste howling wilderness he led him about; he instructed him, he kept him as the apple of his eye. Jer. ii. 2,3.—I remember thee, the kindness of thy youth, the love of thine espousals, when thou wentest after me in the wilderness, in the land that was not sown, etc. Deut. viii. 2,16.—And thou shalt remember all the way which the Lord thy God led thee this forty years in the wilderness, etc. CAMBRIDGE: PRINTED BY S.G. and M.J. FOR JOHN USHER OF BOSTON. 1669. © 2009, MayflowerHistory.com. All Rights Reserved. TO THE RIGHT WORSHIPFUL, THOMAS PRENCE, ESQ., GOVERNOR OF THE JURISDICTION OF NEW PLYMOUTH; WITH THE WORSHIPFUL, THE MAGISTRATES, HIS ASSISTANTS IN THE SAID GOVERNMENT: N.M. wisheth Peace and Prosperity in this life, and Eternal Happiness in that which is to come. -

(King Philip's War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial

Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in The Great Narragansett War (King Philip’s War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Major Jason W. Warren, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin Jr., Advisor Alan Gallay, Kristen Gremillion Peter Mansoor, Geoffrey Parker Copyright by Jason W. Warren 2011 Abstract King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was one of the bloodiest per capita in American history. Although hostile native groups damaged much of New England, Connecticut emerged unscathed from the conflict. Connecticut’s role has been obscured by historians’ focus on the disasters in the other colonies as well as a misplaced emphasis on “King Philip,” a chief sachem of the Wampanoag groups. Although Philip formed the initial hostile coalition and served as an important leader, he was later overshadowed by other sachems of stronger native groups such as the Narragansetts. Viewing the conflict through the lens of a ‘Great Narragansett War’ brings Connecticut’s role more clearly into focus, and indeed enables a more accurate narrative for the conflict. Connecticut achieved success where other colonies failed by establishing a policy of moderation towards the native groups living within its borders. This relationship set the stage for successful military operations. Local native groups, whether allied or neutral did not assist hostile Indians, denying them the critical intelligence necessary to coordinate attacks on Connecticut towns. The English colonists convinced allied Mohegan, Pequot, and Western Niantic warriors to support their military operations, giving Connecticut forces a decisive advantage in the field. -

William Bradford Makes His First Substantial

Ed The Pequot Conspirator White William Bradford makes his first substantial ref- erence to the Pequots in his account of the 1628 Plymouth Plantation, in which he discusses the flourishing of the “wampumpeag” (wam- pum) trade: [S]trange it was to see the great alteration it made in a few years among the Indians themselves; for all the Indians of these parts and the Massachusetts had none or very little of it, but the sachems and some special persons that wore a little of it for ornament. Only it was made and kept among the Narragansetts and Pequots, which grew rich and potent by it, and these people were poor and beggarly and had no use of it. Neither did the English of this Plantation or any other in the land, till now that they had knowledge of it from the Dutch, so much as know what it was, much less that it was a com- modity of that worth and value.1 Reading these words, it might seem that Bradford’s understanding of Native Americans has broadened since his earlier accounts of “bar- barians . readier to fill their sides full of arrows than otherwise.”2 Could his 1620 view of them as undifferentiated, arrow-hurtling sav- ages have been superseded by one that allowed for the economically complex diversity of commodity-producing traders? If we take Brad- ford at his word, the answer is no. For “Indians”—the “poor and beg- garly” creatures Bradford has consistently described—remain present in this description but are now joined by a different type of being who have been granted proper names, are “rich and potent” compared to “Indians,” and are perhaps superior to the English in mastering the American Literature, Volume 81, Number 3, September 2009 DOI 10.1215/00029831-2009-022 © 2009 by Duke University Press Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/american-literature/article-pdf/81/3/439/392273/AL081-03-01WhiteFpp.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 440 American Literature economic lay of the land. -

Permits Issued Summary Detail 05-2018

TOWN OF PLYMOUTH DEPARTMENT OF INSPECTIONAL SERVICES Permits Issued From May 01, 2018 To May 31, 2018 No. Issued Est Cost Fees Paid to Date NEW CONSTRUCTION NEW SINGLE FAMILY DETACHED 31 $6,736,600 69,525.40 NEW SINGLE FAMILY ATTACHED 5 $967,756 9,652.30 NEW 5+ FAMILY 1 $26,000,000 150,885.00 SHED 3 $42,228 272.75 RESIDENTIAL IN-GROUND POOL 3 $153,643 240.00 RESIDENTIAL ABOVE-GROUND POOL 5 $27,100 300.00 TRENCH 1 25.00 COM - ACCESSORY STRUCTURE 2 $57,041 330.00 TEMPORARY TENT 6 750.00 RESIDENTIAL TENT 1 40.00 SIGN 11 $16,500 440.00 DEMO - ALL STRUCTURES - RESIDENTIAL 7 $55,000 1,373.75 TOTAL NEW CONSTRUCTION PERMITS 76 $34,055,868 $233,834.20 CERTIFICATE OF OCCUPANCY NEW SINGLE FAMILY DETACHED 17 0.00 NEW SINGLE FAMILY ATTACHED 33 0.00 MOBILE HOME 1 0.00 COMMERCIAL - NEW STRUCTURE 1 0.00 COMMERCIAL FIT OUT BUILDING 1 0.00 COM - NEW RELIGIOUS 1 0.00 TOTAL CERTIFICATE OF OCCUPANCY PERMITS 54 TEMP CERTIFICATE OF OCCUPANCY COMMERCIAL ADDITION/ALTERATION/CONVERSION 1 0.00 TOTAL TEMP CERTIFICATE OF OCCUPANCY 1 ALTERATIONS RESIDENTIAL ADDITION/ALTERATION/CONVERSION 51 $2,443,830 13,514.30 RESIDENTIAL ADDITION OF DECK OR FARMER'S PORCH 15 $115,190 1,330.50 RESIDENTIAL SIDING 15 $122,357 375.00 RESIDENTIAL ROOFING 38 $355,227 950.00 RES - INSULATION 22 $70,193 550.00 RESIDENTIAL ROOFING & SIDING COMBINATION 4 $86,506 160.00 RESIDENTIAL REPLACEMENT WINDOWS 21 $225,462 840.00 RESIDENTIAL WOODSTOVE 2 $5,610 80.00 RESIDENTIAL SOLAR PANELS 7 $126,605 761.00 COMMERCIAL SOLAR PANELS 1 $480,000 0.00 COMMERCIAL ADDITION/ALTERATION/CONVERSION 16 $5,254,000 13,248.55 COMMERCIAL ROOFING 9 $397,080 500.00 COM - ROOFING & SIDING 8 $714,000 1,400.00 COM - REPLACEMENT WINDOWS 1 $25,000 100.00 TOTAL ALTERATIONS PERMITS 210 $10,421,060 $33,809.35 TOTAL WIRING PERMITS 187 $20,945.00 TOTAL ZONING PERMITS 165 $4,155.00 TOTAL PLUMBING/GAS PERMITS 184 $17,865.00 Grand Total 1,030 $44,476,928 $310,608.55 TOWN OF PLYMOUTH DEPARTMENT OF INSPECTIONAL SERVICES Permits Issued From May 01, 2018 To May 31, 2018 Date Owner Parcel ID No. -

Destination Plymouth

DESTINATION PLYMOUTH Approximately 40 miles from park, travel time 50 minutes: Turn left when leaving Normandy Farms onto West Street. You will cross the town line and West Street becomes Thurston Street. At 1.3 miles from exiting park, you will reach Washington Street / US‐1 South. Turn left onto US‐1 South. Continue for 1.3 miles and turn onto I‐495 South toward Cape Cod. Drive approximately 22 miles to US‐44 E (exit 15) toward Middleboro / Plymouth. Bear right off ramp to US‐44E, in less than ¼ mile you will enter a rotary, take the third exit onto US‐ 44E towards Plymouth. Continue for approximately 14.5 miles. Merge onto US‐44E / RT‐3 South toward Plymouth/Cape Cod for just a little over a mile. Merge onto US‐44E / Samoset St via exit 6A toward Plymouth Center. Exit right off ramp onto US‐ 44E / Samoset St, which ends at Route 3A. At light you will see “Welcome to Historic Plymouth” sign, go straight. US‐44E / Samoset Street becomes North Park Ave. At rotary, take the first exit onto Water Street; the Visitor Center will be on your right with the parking lot behind the building. For GPS purposes the mapping address of the Plymouth Visitor Center – 130 Water Street, Plymouth, MA 02360 Leaving Plymouth: Exit left out of lot, then travel around rotary on South Park Ave, staying straight onto North Park Ave. Go straight thru intersection onto Samoset Street (also known as US‐44W). At the next light, turn right onto US‐44W/RT 3 for about ½ miles to X7 – sign reads “44W Taunton / Providence, RI”.