Pathways of the Past: Part 1 Maurice Robbins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

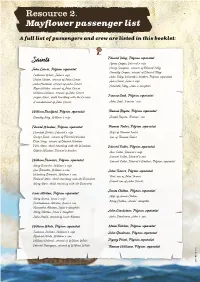

Resource 2 Mayflower Passenger List

Resource 2. Mayflower passenger list A full list of passengers and crew are listed in this booklet: Edward Tilley, Pilgrim separatist Saints Agnus Cooper, Edward’s wife John Carver, Pilgrim separatist Henry Sampson, servant of Edward Tilley Humility Cooper, servant of Edward Tilley Catherine White, John’s wife John Tilley, Edwards’s brother, Pilgrim separatist Desire Minter, servant of John Carver Joan Hurst, John’s wife John Howland, servant of John Carver Elizabeth Tilley, John’s daughter Roger Wilder, servant of John Carver William Latham, servant of John Carver Jasper More, child travelling with the Carvers Francis Cook, Pilgrim separatist A maidservant of John Carver John Cook, Francis’ son William Bradford, Pilgrim separatist Thomas Rogers, Pilgrim separatist Dorothy May, William’s wife Joseph Rogers, Thomas’ son Edward Winslow, Pilgrim separatist Thomas Tinker, Pilgrim separatist Elizabeth Barker, Edward’s wife Wife of Thomas Tinker George Soule, servant of Edward Winslow Son of Thomas Tinker Elias Story, servant of Edward Winslow Ellen More, child travelling with the Winslows Edward Fuller, Pilgrim separatist Gilbert Winslow, Edward’s brother Ann Fuller, Edward’s wife Samuel Fuller, Edward’s son William Brewster, Pilgrim separatist Samuel Fuller, Edward’s Brother, Pilgrim separatist Mary Brewster, William’s wife Love Brewster, William’s son John Turner, Pilgrim separatist Wrestling Brewster, William’s son First son of John Turner Richard More, child travelling with the Brewsters Second son of John Turner Mary More, child travelling -

William Bradford's Life and Influence Have Been Chronicled by Many. As the Co-Author of Mourt's Relation, the Author of of Plymo

William Bradford's life and influence have been chronicled by many. As the co-author of Mourt's Relation, the author of Of Plymouth Plantation, and the long-term governor of Plymouth Colony, his documented activities are vast in scope. The success of the Plymouth Colony is largely due to his remarkable ability to manage men and affairs. The information presented here will not attempt to recreate all of his activities. Instead, we will present: a portion of the biography of William Bradford written by Cotton Mather and originally published in 1702, a further reading list, selected texts which may not be usually found in other publications, and information about items related to William Bradford which may be found in Pilgrim Hall Museum. Cotton Mather's Life of William Bradford (originally published 1702) "Among those devout people was our William Bradford, who was born Anno 1588 in an obscure village called Ansterfield... he had a comfortable inheritance left him of his honest parents, who died while he was yet a child, and cast him on the education, first of his grand parents, and then of his uncles, who devoted him, like his ancestors, unto the affairs of husbandry. Soon a long sickness kept him, as he would afterwards thankfully say, from the vanities of youth, and made him the fitter for what he was afterwards to undergo. When he was about a dozen years old, the reading of the Scripture began to cause great impressions upon him; and those impressions were much assisted and improved, when he came to enjoy Mr. -

RELIGIOUS CONTROVERSIES in PLYMOUTH COLONY by Richard Howland Maxwell Pilgrim Society Note, Series Two, June 1996

RELIGIOUS CONTROVERSIES IN PLYMOUTH COLONY by Richard Howland Maxwell Pilgrim Society Note, Series Two, June 1996 Plymouth Colony was born out of a religious controversy and was not itself immune to such controversies. The purpose of this lecture is to consider some of those controversies in order that we may better understand the Pilgrims, their attitudes, and their relationships with some other individuals and groups. We will start with some background concerns central to the identity of the Plymouth group, then move on to consider the relationships the Pilgrims had with some of their clergy, and focus finally on two groups who were not welcome in Plymouth or any other English colony. I wish to begin with two pairs of terms and concepts about which we seem often to find confusion. The first pair is Pilgrims and Puritans - or more accurately, Separatists and other Puritans. Some of you have heard me expound on this theme before, and it is not my intention to repeat that presentation. To understand the Pilgrims, however, we need to understand the religious and cultural background from which they came. We need also, I think, to understand something about their neighbors to the north, who shared their background but differed with them in some important ways. That shared background is the Puritan movement within the Church of England. The most succinct description of Puritanism that I have read comes from Bradford Smith’s biography titled Bradford of Plymouth. Smith wrote: Puritanism in England was essentially a movement within the established church for the purifying of that church - for ministers godly and able to teach, for a simplifying of ritual, for a return to the virtues of primitive Christianity. -

CHILDREN on the MAYFLOWER by Ruth Godfrey Donovan

CHILDREN ON THE MAYFLOWER by Ruth Godfrey Donovan The "Mayflower" sailed from Plymouth, England, September 6, 1620, with 102 people aboard. Among the passengers standing at the rail, waving good-bye to relatives and friends, were at least thirty children. They ranged in age from Samuel Eaton, a babe in arms, to Mary Chilton and Constance Hopkins, fifteen years old. They were brought aboard for different reasons. Some of their parents or guardians were seeking religious freedom. Others were searching for a better life than they had in England or Holland. Some of the children were there as servants. Every one of the youngsters survived the strenuous voyage of three months. As the "Mayflower" made its way across the Atlantic, perhaps they frolicked and played on the decks during clear days. They must have clung to their mothers' skirts during the fierce gales the ship encountered on other days. Some of their names sound odd today. There were eight-year-old Humility Cooper, six-year-old Wrestling Brewster, and nine-year-old Love Brewster. Resolved White was five, while Damans Hopkins was only three. Other names sound more familiar. Among the eight-year- olds were John Cooke and Francis Billington. John Billington, Jr. was six years old as was Joseph Mullins. Richard More was seven years old and Samuel Fuller was four. Mary Allerton, who was destined to outlive all others aboard, was also four. She lived to the age of eighty-three. The Billington boys were the mischief-makers. Evidently weary of the everyday pastimes, Francis and John, Jr. -

William Bradford Et Al

William Bradford et al. Mayflower Compact (1620) IN THE NAME OF GOD, AMEN. We, whose names are underwritten, the Loyal Subjects of our dread Sovereign Lord King James, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith, &c. Having undertaken for the Glory of God, and Advancement of the Christian Faith, and the Honour of our King and Country, a Voyage to plant the first Colony in the northern Parts of Virginia; Do by these Presents, solemnly and mutually, in the Presence of God and one another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil Body Politick, for our better Ordering and Preservation, and Furtherance of the Ends aforesaid: And by Virtue hereof do enact, constitute, and frame, such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions, and Officers, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general Good of the Colony; unto which we promise all due Submission and Obedience. IN WITNESS whereof we have hereunto subscribed our names at Cape-Cod the eleventh of November, in the Reign of our Sovereign Lord King James, of England, France, and Ireland, the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth, Anno Domini; 1620. Mr. John Carver, Mr. Samuel Fuller, Edward Tilly, Mr. William Bradford, Mr. Christopher Martin, John Tilly, Mr Edward Winslow, Mr. William Mullins, Francis Cooke, Mr. William Brewster. Mr. William White, Thomas Rogers, Isaac Allerton, Mr. Richard Warren, Thomas Tinker, Myles Standish, John Howland, John Ridgdale John Alden, Mr. Steven Hopkins, Edward Fuller, John Turner, Digery Priest, Richard Clark, Francis Eaton, Thomas Williams, Richard Gardiner, James Chilton, Gilbert Winslow, Mr. -

An Investigation Into Weston's Colony at Wessagussett Weymouth, MA Craig S

Plymouth Archaeological Rediscovery Project (PARP) An Investigation into Weston's Colony at Wessagussett Weymouth, MA Craig S. Chartier MA www.plymoutharch.com March 2011 The story of the 1622 plantation at Wessagusset begins with Master Thomas Weston. Weston was a wealthy London merchant and ironmonger and one of the original backers of the Plymouth colonists’ plantation in the New World. Weston personally traveled to Leiden, Holland to convince the Plymouth colonists not to negotiate with the Dutch or the Virginia Company for the right to settle in their New World lands (Davis 1908:63). Weston informed them that he and a number of other merchants would be the Adventurers who would personally finance their colony. He also informed them that Sir Ferdinando Gorges had obtained a patent for land in the northern part of Virginia that they had named “New England,” and that they could be establishing a colony at any time (Davis 1908:66). Unfortunately, after the conditions were drawn up, agreed upon in Holland and sent back to England, the Adventurers, with Weston being specifically named, changed some of the particulars, and the colonists, having already sold everything to finance the venture, had to agree to the altered terms (Davis 1908: 66). Weston became the chief agent and organizer of the venture which led some of the settlers, such as John Robinson, Samuel Fuller, William Bradford, Isaac Allerton, and Edward Winslow to fear laying their fate in the hands of one man alone (Davis 1908:66, 71). The London merchant Adventurers agreed to finance the voyage in order to see personal gain through the shipping of lumber, sassafras, and fur back to them from the Plymouth Colony. -

The Allertons of New England and Virginia

:V:.^v,,:o\.. , ....... ^:^^- V > r- -*" •iMt. •-» A ^ '<^^^**^^-' '^'•^t;^' *'_-':^'*«'*4>''i;^.' ••^J« ''!«*i ^2^ .^ >i7! ;^ 51 Hati C^*^. '^'T^i: t. * /.' t" -^^ tk/. ;^:]cv r^ "Bl >9 ,ST\.Airi^ MO "--I; /-' ,Q^'^ Given By t 3^ C&l 1 X /J 3^7. /yj~ ALLERTONS OF NEW ENGLAND AND VIRGINIA. By Isaac J. Greenwood, A.M., of New York city. Ot{,%\^\^l,- Reprinted from N. England HistcJrical and Genealogical Register for July, 1890. ALLERTON, a young tailor from London, was married at the ISAAC^Stadhuis, Leyden, 4 November, 1611, to Mary Norris (Savage says " Collins"), maid from Newbury, co. Berks. At the same time and place was married his sister Sarah, widow of John Vincent, of London, to Degory Priest, hatter, from the latter place.* Priest, freeman of Leyden 16 November, 1615, came out on the Mayflower in 1620, and died, soon after 1 1620-1 his married landing, January, ; widow, who had remained behind, 3d, at Leyden, 13 November, 1621, Goddard Godbert (or Cuthbert Cuth- bertson), a Dutchman, who came with his wife to Plymouth in the Ann, 1623, and both died in 1633. Allerton a freeman of Leyden 7 February 1614; save his brother-in-law Priest, and the subsequent Governor of the Colony, Wm. Bradford, none others of the company appear to have attained this honor. He was one of the Mayflower pilgrims in 1620, and was accompanied by his wife Mary, and his children Bartholomew, Remember and Mary. John Allerton, a sailor, who designed settling in the new colony, died before the vessel sailed on her return voyage, and Mrs. -

Mayflower Chronicles

Mayflower Chronicles Colony Officers Colony Governor Albany Colony Spring Meeting David W. Morton Ed.D. Saturday, May 7, 2016 Noon 1st Dep. Colony Gov. Normanside Country Club, Delmar, NY Walley Francis Colony Governor’s Message May 7, 2016 At our May 7th Luncheon, Sylvia Hasenkopf (professional researcher, historian, and 2ndDep. Colony Gov. genealogist) will give a presentation on the "Hometown Heroes Banner Program." She was Sara L.French Ph.D. instrumental in initiating the original project for the Town of Cairo and continues to oversee its implementation under the auspices of the Cairo Historical Society. Secretary This program is a living tribute to the servicemen and women from the Town of Cairo who Priscilla S. Davis have served our country from as far back as the French and Indian War to the present day. Each colorful, durable, professionally produced banner honors a specific individual and incudes their picture (where available), branch of service, and the military conflict in which Treasurer they served. The banners are suspended from lampposts along the streets of the town from Betty-Jean Haner May to September. Captain 1 Mrs. Hasenkopf, who is also the administrator of the voluminous website "Tracing Your Roots in Greene County," is currently preparing for the publication, this summer, of the first Julia W. Carossella book of these Hometown Heroes with additional information she has compiled on their lives and military service. (Thanks to Sylvia Story Magin for finding this program.) Captain 2 In this issue of the Mayflower Chronicles, we have included our Albany Colony Proposed Douglas M. (Tim) Mabee Bylaws that you will be asked to discuss and vote upon at the May 7th Luncheon. -

Investigate Mayflower Biographies

Mayflower Biographies On 16th September 1620 the Mayflower set sail with 102 passengers plus crew (between 30 & 40). They spotted land in America on 9th November. William Bradford’s writings… William Bradford travelled on the Mayflower and he has left us some fantastic details about the passengers and settlers. The next few pages have some extracts from his writings. Bradford wrote: ‘The names of those which came over first, in the year 1620, and were by the blessing of God the first beginners and in a sort the foundation of all the Plantations and Colonies in New England; and their families.’ He ended the writings with the words: ‘From William Bradford, Of Plimoth Plantation, 1650’ Read ` If you want to read more see the separate document their Mayflower Biographies Also Click here to link to the stories… Mayflower 400 website Read their stories… Mr. John Carver, Katherine his wife, Desire Minter, and two manservants, John Howland, Roger Wilder. William Latham, a boy, and a maidservant and a child that was put to him called Jasper More. John was born by about 1585, making him perhaps 35 when the Mayflower sailed. He may have been one of the original members of the Scrooby Separatists. Katherine Leggatt was from a Nottinghamshire family and it’s thought that they married in Leiden before 1609. They buried a child there in 1617. In 1620, John was sent from Holland to London to negotiate the details of the migration. John was elected the governor of the Mayflower and, on arrival in America, he became the governor of the colony too. -

February 2009

The Society of Mayflower Descendants in the State of Connecticut Nutmeg Gratings March 2009 Volume 29, Number 1 overnor’s Message In closing let me say that your Society is a society of volunteers. If any of you It was my great honor, along would like to share your with deputy governor general talents please let any of the Mary Brown, to head the Society’s officers know. We Connecticut Society’s would welcome your help. delegation to the 38th General Congress of the General Don Studley Society of Mayflower Descendants on September 7 at Plymouth. The General Congress, held every three years, is a wonderful opportunity to renew acquaintances, make new friends and learn more about all the work done by our Society. A full report of the proceedings of the Congress is contained in the December, 2008 Mayflower Quarterly. It does not, however, contain the Connecticut Society report, which is in this issue of Gratings, on page 8. In This Issue Judith Swan of California was elected Governor General at the General Congress and has indicated an ambitious program Governor’s Message 1 focused on education, records preservation and the Mayflower Officers & Committees 2 House. To that end she has established a Women of the Mayflower Committee to honor the female passengers. This is a New Members 3 long overdue initiative and we look forward to its full implementation. April Luncheon 4 Protestant Reformation We also look forward to the Society’s efforts with regard to Series 5 records preservation. Recent technological advances, coupled with the fact that some of our records are now more than 100 Report to General Society 8 years old, make guidance on records preservation a high priority of the Connecticut Society as well as the General Society. -

"The First Thanksgiving" at Plymouth

PRIMARY SOURCES FOR "THE FIRST THANKSGIVING" AT PLYMOUTH There are 2 (and only 2) primary sources for the events of autumn 1621 in Plymouth: Edward Winslow writing in Mourt's Relation and William Bradford writing in Of Plymouth Plantation Edward Winslow, Mourt's Relation: "our harvest being gotten in, our governour sent foure men on fowling, that so we might after a speciall manner rejoyce together, after we had gathered the fruits of our labours ; they foure in one day killed as much fowle, as with a little helpe beside, served the Company almost a weeke, at which time amongst other Recreations, we exercised our Armes, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and amongst the rest their greatest king Massasoyt, with some ninetie men, whom for three dayes we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five Deere, which they brought to the Plantation and bestowed on our Governour, and upon the Captaine and others. And although it be not always so plentifull, as it was at this time with us, yet by the goodness of God, we are so farre from want, that we often wish you partakers of our plentie." In modern spelling "our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a special manner rejoice together, after we had gathered the fruits of our labors; they four in one day killed as much fowl, as with a little help beside, served the Company almost a week, at which time amongst other Recreations, we exercised our Arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and amongst the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five Deer, which they brought to the Plantation and bestowed on our Governor, and upon the Captain and others. -

Newsletter of the Society of Mayflower Descendants in the State of Florida

Newsletter of the Society of Mayflower Descendants in the State of Florida The Mayflower Chartered 31 July 1937 by Dr. Jeremy Dupertuis Bangs Director, Leiden American Pilgrim Museum Leiden, Netherlands Copyright (c) 2011-2016 J. D. Bangs. 2017-02 May Kenneth E. Carter, Editor All rights reserved. Used with Dr. Bangs’ written permission. GOVERNOR’S MESSAGE The Spring BoA Meeting was held in Tampa last Saturday and well attended by FSMD Officers and Colony Governors—lots of discussions were had and decisions made. Kathleen and I have had the pleasure to visit 14 of the 17 colonies and will visit another on Saturday, 6 May—and we are looking forward to it. We have a very busy Summer and Fall season planned— we will be visiting our new great-granddaughter in July in Tacoma, WA; attending the GBOA Congress Meeting in September in Plymouth, MA; and then returning to New England to attend the wedding of our youngest granddaughter, Erin in October in Maine. We wish all of you a very safe and happy Summer and <><> IN THIIS ISSUE <><> Fall and look forward to seeing all of you at the Fall BoA Meeting to be held in The Villages, hosted by the James Governor’s Message 1 Chilton Colony, on 17-18 November. Hotel & registration News from our Colonies 2-6 forms are on the FSMD website—make your reservations Meet our new Counselor 7 early. See you there! News of Interest ` 8-9 Fall Meeting 2017 10-11 Ken Membership Changes 12-13 Kenneth E. Carter Spring BoA Minutes 14-20 FSMD Governor Legal “Stuff” from Editor 21 The Florida Pilgrim - 2017-2-May Page 1 <><><><> NEWS FROM ACROSS THE SUNSHINE STATE - OUR COLONIES IN ACTION <><><><> Governor William Bradford Colony—St.