The Dutch & Swedes on the Delaware

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women Investors and the Virginia Company in the Early Seventeenth Century

The University of Manchester Research Women Investors and the Virginia Company in the Early Seventeenth Century DOI: 10.1017/s0018246x19000037 Document Version Accepted author manuscript Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Ewen, M. (2019). Women Investors and the Virginia Company in the Early Seventeenth Century. The Historical Journal, 62(4), 853-874. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0018246x19000037 Published in: The Historical Journal Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:07. Oct. 2021 WOMEN INVESTORS AND THE VIRGINIA COMPANY IN THE EARLY SEVENTEENTH CENTURY* MISHA EWEN University of Manchester WOMEN INVESTORS Abstract. This article explores the role of women investors in the Virginia Company during the early seventeenth century, arguing that women determined the success of English overseas expansion not just by ‘adventuring’ their person, but their purse. -

Discord, Order, and the Emergence of Stability in Early Bermuda, 1609-1623

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1991 "In the Hollow Lotus-Land": Discord, Order, and the Emergence of Stability in Early Bermuda, 1609-1623 Matthew R. Laird College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Laird, Matthew R., ""In the Hollow Lotus-Land": Discord, Order, and the Emergence of Stability in Early Bermuda, 1609-1623" (1991). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625691. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-dbem-8k64 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. •'IN THE HOLLOW LOTOS-LAND": DISCORD, ORDER, AND THE EMERGENCE OF STABILITY IN EARLY BERMUDA, 1609-1623 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Matthew R. Laird 1991 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Matthew R. Laird Approved, July 1991 -Acmy James Axtell Thaddeus W. Tate TABLE OP CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................... iv ABSTRACT...............................................v HARBINGERS....... ,.................................... 2 CHAPTER I. MUTINY AND STARVATION, 1609-1615............. 11 CHAPTER II. ORDER IMPOSED, 1615-1619................... 39 CHAPTER III. THE FOUNDATIONS OF STABILITY, 1619-1623......60 A PATTERN EMERGES.................................... -

PDF Scan to USB Stick

REVIEWS Alf Åberg. FOLKET I NYA SVERIGE. VÅR KOLONI VID DELAWAREFLODEN 1638-1655. Stockholm: Natur och Kultur, 1987. 198 pp., illustrated. Voluminous and detailed as the scholarly literature about the seventeenth-century Swedish settlements on the Delaware River has been down through the centuries, Alf Åberg makes no claim of contributing anything essentially new to the subject of this modest volume. Rather his purpose has been to retell the story of this footnote to Swedish history for the modern layman who reads Swedish on the occasion of the 350th anniversary of the founding of New Sweden, Nova Sveda [Nya Sverige], 1638). As usual, Alf Åberg has succeeded remarkably well in fulfilling his purpose—so well, in fact, that a translation into American English of Folket i Nya Sverige can be recommended with enthusiasm. By soberly and sensibly confining himself to the facts as we presently are able to discern them, Alf Åberg draws repeated attention to two leitmotifs, so to speak, that resound throughout his chronological retelling of the story itself: the international coopera• tive—and competitive—effort that the enterprise essentially was and the penchant toward failure, rather than success, that typified it. To expand briefly on these themes, Swedish and Dutch capital was required to finance the initial voyage of the ships Kalmar Nyckel and Gripen in their pursuit of such viable commodities as tobacco and furs; and since the Dutch then had far greater expertise at seafaring than did the Swedes, the leadership and most of the sailors for these vessels were recruited in Amsterdam rather than the fledgling seaport of Göteborg. -

Collections of the Virginia Historical Society, in Which Are Also Many Other MSS

Ml: Gc 975.5 V823C V.7 1219029 GENEALOGY COLLECTION ALLEN COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY 3 1833 00826 8341 COLLECTIONS Virginia Historical Society. New Series. VOL. VII. WM. ELLIS JONES, PRINTER, RICHMOND, VA. ABSTRACT OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE VirginiaCompany of London, I 6 I 9— I 624, PREPARED FROM THE RECORDS IN THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS BY CONWAY ROBINSON, AND EDITED WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY R. A. BROCK, Corresponding Secretary and Librarian of the Society. VOL. I. Richmond, Virginia. PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY. MDCCCLXXXVIII. /^^ .H 1219029 INTRODUCTION. The essential value of the Proceedings of the Virginia Com- pany of London, towards a due knowledge of the planting of the first of the American Commonwealths, is patent. Although highly useful excerpts from them have been presented by the zealous and indefatigable investigator, Rev. Edward D. Neill, D. D., in his publications illustrative of the early history of Virginia, it is believed that the abstracts now offered will prove an acceptable aggrandizement of his labors, and inasmuch as they were prepared by a scholar of singular discernment— the late eminent jurist, Conway Robinson, whose professional works are held in prime authority and as of enduring worth— it may be hoped, with confidence, that they are comprehensive as to all desirable details. The Virginia Historical Society is greatly indebted to Mr. Robinson for a signal devotion to its interests, which only ceased with his life. He was one of its founders, on December 29th, his removal to Wash- 1831 ; its first treasurer; from 1835 until ington, D. C, in 1869, a member of its " Standing," or Executive Committee, serving for a greater portion of the period as chair- man, and subsequently and continuously as vice-president of the Society. -

The East India Company: Agent of Empire in the Early Modern Capitalist Era

Social Education 77(2), pp 78–81, 98 ©2013 National Council for the Social Studies The Economics of World History The East India Company: Agent of Empire in the Early Modern Capitalist Era Bruce Brunton The world economy and political map changed dramatically between the seventeenth 2. Second, while the government ini- and nineteenth centuries. Unprecedented trade linked the continents together and tially neither held ownership shares set off a European scramble to discover new resources and markets. European ships nor directed the EIC’s activities, it and merchants reached across the world, and their governments followed after them, still exercised substantial indirect inaugurating the modern eras of imperialism and colonialism. influence over its success. Beyond using military and foreign policies Merchant trading companies, exem- soon thereafter known as the East India to positively alter the global trading plified by the English East India Company (EIC), which gave the mer- environment, the government indi- Company, were the agents of empire chants a monopoly on all trade east of rectly influenced the EIC through at the dawn of early modern capital- the Cape of Good Hope for 15 years. its regularly exercised prerogative ism. The East India Company was a Several aspects of this arrangement to evaluate and renew the charter. monopoly trading company that linked are worth noting: Understanding the tension in this the Eastern and Western worlds.1 While privilege granting-receiving relation- it was one of a number of similar compa- 1. First, the EIC was a joint-stock ship explains much of the history of nies, both of British origin (such as the company, owned and operated by the EIC. -

Kalmar Nyckel: Using a 17Th Century Dutch Pinnace to Teach Physics and More DTI 2016-2017 Ancient Inventions

Kalmar Nyckel: Using a 17th century Dutch Pinnace to Teach Physics and More DTI 2016-2017 Ancient Inventions Terri Eros Challenges H.B. duPont Middle School, while located in a very suburban setting, serves a very diverse population. There are approximately 900 students in grades 6-8, with students almost evenly split between urban and suburban backgrounds. The academic readiness also varies greatly with relation to reading and math skills. It is not unusual to have a range of students reading all the way from a pre-primer level to those comfortable with high school text. In some cases the disparity is due to limited English proficiency. The math skills are similarly distributed with some students needing calculators for 2-digit addition while others are comfortable solving algebraic equations. To better meet student needs, our school piloted having honors classes in Science and Social Studies last year. Groupings were based on reading level for Social Studies and Math level for Science. The outcome was less than ideal for Science. At the middle school level, language skills are more important so that is now the basis of grouping for the 2016-2017 school year. In addition, our school is aiming for full inclusion. Students include those that have severe physical and/or emotional needs that interfere with their ability to interact linguistically, through either speech or writing. Despite these limitations, there is still an interest and an expectation to succeed in the Science classroom. The challenge is to incorporate the rigor of the Next Generation Science Standards, with its emphasis on student driven learning, while finding multiple access points for the students based on readiness. -

Kalmar Nyckel – a Guide to the Ship and Her History

Kalmar Nyckel – A Guide to the Ship and Her History Kalmar Nyckel – A Guide to the Ship and Her History 2 Guide to the Re‐creation of the Tall Ship KALMAR NYCKEL “Become Something Great” America’s original promise and enduring challenge. Excerpt from a letter by Peter Minuit to Swedish Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna As navigation makes kingdoms and countries thrive and in the WestIndies [North America] many places gradually come to be occupied by the English, Dutch, and French, I think the Swedish Crown ought not to stand back and refrain from having her name spread widely, also in foreign countries; and to that end I the undersigned, wish to offer my services to the Swedish The Kalmar Nyckel Foundation Crown to set out modestly on what might, by God’s Written & Compiled By grace, become something great within a short Samuel Heed, Esq. time [emphasis added]. With Captain Lauren Morgens & Alistair Gillanders, Esq. Firstly, I have suggested to Mr. Pieter Spiering [Spiring, Swedish Ambassador to the Hague] to make a journey to the Virginias, New Netherland and other places, in which regions certain places are well known to me, with a very good climate, which could be named Nova Sweediae [New Sweden]…. Your Excellency’s faithful servant, Cover photograph: The present day Kalmar Nyckel cruising on the Pieter Minuit Patuxent river on the Chesapeake during a visit to Solomon’s Island, MD in 2008. Photographer – Alistair Gillanders. Amsterdam, 15 June 1636 Copyright ©2009 Kalmar Nyckel Foundation. All rights reserved. Ship and History Guide – Version 1.01 Kalmar Nyckel – A Guide to the Ship and Her History 3 Table of Contents 7.1.3 The Main Deck and Its Features: .............................................. -

Before Albany

Before Albany THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Regents of the University ROBERT M. BENNETT, Chancellor, B.A., M.S. ...................................................... Tonawanda MERRYL H. TISCH, Vice Chancellor, B.A., M.A. Ed.D. ........................................ New York SAUL B. COHEN, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. ................................................................... New Rochelle JAMES C. DAWSON, A.A., B.A., M.S., Ph.D. ....................................................... Peru ANTHONY S. BOTTAR, B.A., J.D. ......................................................................... Syracuse GERALDINE D. CHAPEY, B.A., M.A., Ed.D. ......................................................... Belle Harbor ARNOLD B. GARDNER, B.A., LL.B. ...................................................................... Buffalo HARRY PHILLIPS, 3rd, B.A., M.S.F.S. ................................................................... Hartsdale JOSEPH E. BOWMAN,JR., B.A., M.L.S., M.A., M.Ed., Ed.D. ................................ Albany JAMES R. TALLON,JR., B.A., M.A. ...................................................................... Binghamton MILTON L. COFIELD, B.S., M.B.A., Ph.D. ........................................................... Rochester ROGER B. TILLES, B.A., J.D. ............................................................................... Great Neck KAREN BROOKS HOPKINS, B.A., M.F.A. ............................................................... Brooklyn NATALIE M. GOMEZ-VELEZ, B.A., J.D. ............................................................... -

The 1693 Census of the Swedes on the Delaware

THE 1693 CENSUS OF THE SWEDES ON THE DELAWARE Family Histories of the Swedish Lutheran Church Members Residing in Pennsylvania, Delaware, West New Jersey & Cecil County, Md. 1638-1693 PETER STEBBINS CRAIG, J.D. Fellow, American Society of Genealogists Cartography by Sheila Waters Foreword by C. A. Weslager Studies in Swedish American Genealogy 3 SAG Publications Winter Park, Florida 1993 Copyright 0 1993 by Peter Stebbins Craig, 3406 Macomb Steet, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20016 Published by SAG Publications, P.O. Box 2186, Winter Park, Florida 32790 Produced with the support of the Swedish Colonial Society, Philadelphia, Pa., and the Delaware Swedish Colonial Society, Wilmington, Del. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 92-82858 ISBN Number: 0-9616105-1-4 CONTENTS Foreword by Dr. C. A. Weslager vii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: The 1693 Census 15 Chapter 2: The Wicaco Congregation 25 Chapter 3: The Wicaco Congregation - Continued 45 Chapter 4: The Wicaco Congregation - Concluded 65 Chapter 5: The Crane Hook Congregation 89 Chapter 6: The Crane Hook Congregation - Continued 109 Chapter 7: The Crane Hook Congregation - Concluded 135 Appendix: Letters to Sweden, 1693 159 Abbreviations for Commonly Used References 165 Bibliography 167 Index of Place Names 175 Index of Personal Names 18 1 MAPS 1693 Service Area of the Swedish Log Church at Wicaco 1693 Service Area of the Swedish Log Church at Crane Hook Foreword Peter Craig did not make his living, or support his four children, during a career of teaching, preparing classroom lectures, or burning the midnight oil to grade examination papers. -

The English Atlantic World: a View from London Alison Games Georgetown University

The English Atlantic World: A View from London Alison Games Georgetown University William Booth occupied an unfortunate status in the land of primogeniture and the entailed estate. A younger son from a Cheshire family, he went up to London in May, 1628, "to get any servis worth haveinge." His letters to his oldest brother John, who had inherited the bulk of their father's estate, and John's responses, drafted on the back of William's original missives, describe the circumstances which enticed men to London in search of work and the misfortunes that subsequently ushered them overseas. William Booth, unable to find suitable employment in the metropolis, implored his brother John to procure a letter of introduction on his behalf from their cousin Morton. Plaintively reminding his brother "how chargeable a place London is to live in," he also requested funds for a suit of clothes in order to make himself more presentable in his quest for palatable employment. William threatened his older brother with military service on the continent if he could find no position in London, preferring to "goe into the lowcuntries or eles wth some man of warre" than to stay in London. John Booth, dismayed by his sibling's martial inclination, offered William money from his own portion of their father's estate rather than permit William to squander his own smaller share. In what proved to be a gross misreading of William's character but perhaps a sound assessment of his desire for the status becoming his ambitions, John urged William to seek a position with a bishop. -

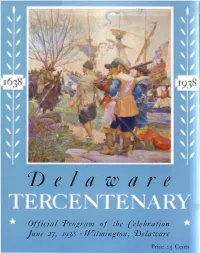

Delaware Tercentenary Program

Vela ware Official Program., of the Celebration June 27, I9J8 ·Wilmington, 'Delaware Price 25 Cents FORT CHRISTINA H.M. CHRISTINA, Queen of Sweden (r6J'l-l 654) during H.M. GusTAvus A oo LPH U s , King of Sweden (161 '· whose reign New Sweden was founded. I 632) through whose support New Sweden becan1e a possibility. l DEcEMBER 1637, the Swedish Expedi tion, under Peter Minuit, sailed from Sweden in the ship, "Kalmar Nyckel" and the yacht,"Fogel Grip," and finally reached the "Rocks" in March r6J8. Here Minui t made a treaty with the Indians and, with a salute of two cannons, claimed for Sweden all that land from the Christina River down to Bombay Hook. Wt�forl(g� ?t�dfantt� �fnur }llttttbetaCONTRACTET gnga(n�cat�ct S�bre �mpagnict �tbf J(onuugart;rctj ewcrfg�c. 6rdlc iam·om �it�dm &\jffdin�. £)�uu 4/ft6tt 9?tl)trfdnb(rc �prdfct �fau p.S6�Mnfl.al 2ft' ~ £ BEGINNINGS of the establishment of New }:RICO SCHRODERO. L S~eden rnay be traced back to the efforts of one William Usselinx, a native of Antwerp, who interested King Gustavus Adolphus in the enter prise. At the right is reproduced the cover of the contract and prospectus which was used to interest The Cover investors in the venture. Here is reproduced the famous painting by Stanley M. Arthurs, Esq., ofthe landing ofthe .firstSwedish expedi tion at the "Roclcs." The painting is owned by Joseph S. Wilson, Esq. GusTAF V ' K.lng • of S weden , d u r .1 n g . w h ose reign, In I9J8 , t h e ter- centenary of · the found·lng of N ew Sweden IS celebrated. -

Chronology of Colonial Swedes on the Delaware 1638-1713 by Dr

Chronology of Colonial Swedes on the Delaware 1638-1713 by Dr. Peter Stebbins Craig Fellow, American Society of Genealogists Fellow, Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania Historian, Swedish Colonial Society originally published in Swedish Colonial News, Volume 2, Number 5 (Fall 2001) Although it is commonly known that the Swedes were the first white settlers to successfully colonize the Delaware Valley in 1638, many historians overlook the continuing presence of the Delaware Swedes throughout the colonial period. Some highlights covering the first 75 years (1638-1713) are shown below: New Sweden Era, 1638-1655 1638 - After a 4-month voyage from Gothenburg, Kalmar Nyckel arrives in the Delaware in March. Captain Peter Minuit purchases land on west bank from the Schuylkill River to Bombay Hook, builds Fort Christina at present Wilmington and leaves 24 men, under the command of Lt. Måns Kling, to man the fort and trade with Indians. Kalmar Nyckel returns safely to Sweden, but Minuit dies on return trip in a hurricane in the Caribbean. 1639 - Fogel Grip, which accompanied Kalmal Nyckel, brings a 25th man from St. Kitts, a slave from Angola known as Anthony Swartz. 1640 - Kalmar Nyckel, on its second voyage, brings the first families to New Sweden, including those of Sven Gunnarsson and Lars Svensson. Other new settlers include Peter Rambo, Anders Bonde, Måns Andersson, Johan Schaggen, Anders Dalbo and Dr. Timen Stiddem. Lt. Peter Hollander Ridder, who succeeds Kling as new commanding officer, purchases more land from Indians between Schuylkill and the Falls of the Delaware. 1641 - Kalmar Nyckel, joined by the Charitas, brings 64 men to New Sweden, including the families of Måns Lom, Olof Stille, Christopher Rettel, Hans Månsson, Olof Thorsson and Eskil Larsson.