List of Calidris Waders with References

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 7: Species Changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015)

IUCN Red List version 2015.4: Table 7 Last Updated: 19 November 2015 Table 7: Species changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015) Published listings of a species' status may change for a variety of reasons (genuine improvement or deterioration in status; new information being available that was not known at the time of the previous assessment; taxonomic changes; corrections to mistakes made in previous assessments, etc. To help Red List users interpret the changes between the Red List updates, a summary of species that have changed category between 2014 (IUCN Red List version 2014.3) and 2015 (IUCN Red List version 2015-4) and the reasons for these changes is provided in the table below. IUCN Red List Categories: EX - Extinct, EW - Extinct in the Wild, CR - Critically Endangered, EN - Endangered, VU - Vulnerable, LR/cd - Lower Risk/conservation dependent, NT - Near Threatened (includes LR/nt - Lower Risk/near threatened), DD - Data Deficient, LC - Least Concern (includes LR/lc - Lower Risk, least concern). Reasons for change: G - Genuine status change (genuine improvement or deterioration in the species' status); N - Non-genuine status change (i.e., status changes due to new information, improved knowledge of the criteria, incorrect data used previously, taxonomic revision, etc.); E - Previous listing was an Error. IUCN Red List IUCN Red Reason for Red List Scientific name Common name (2014) List (2015) change version Category Category MAMMALS Aonyx capensis African Clawless Otter LC NT N 2015-2 Ailurus fulgens Red Panda VU EN N 2015-4 -

Nordmann's Greenshank Population Analysis, at Pantai Cemara Jambi

Final Report Nordmann’s Greenshank Population Analysis, at Pantai Cemara Jambi Cipto Dwi Handono1, Ragil Siti Rihadini1, Iwan Febrianto1 and Ahmad Zulfikar Abdullah1 1Yayasan Ekologi Satwa Alam Liar Indonesia (Yayasan EKSAI/EKSAI Foundation) Surabaya, Indonesia Background Many shorebirds species have declined along East Asian-Australasian Flyway which support the highest diversity of shorebirds in the world, including the globally endangered species, Nordmann’s Greenshank. Nordmann’s Greenshank listed as endangered in the IUCN Red list of Threatened Species because of its small and declining population (BirdLife International, 2016). It’s one of the world’s most threatened shorebirds, is confined to the East Asian–Australasian Flyway (Bamford et al. 2008, BirdLife International 2001, 2012). Its global population is estimated at 500–1,000, with an estimated 100 in Malaysia, 100–200 in Thailand, 100 in Myanmar, plus unknown but low numbers in NE India, Bangladesh and Sumatra (Wetlands International 2006). The population is suspected to be rapidly decreasing due to coastal wetland development throughout Asia for industry, infrastructure and aquaculture, and the degradation of its breeding habitat in Russia by grazing Reindeer Rangifer tarandus (BirdLife International 2012). Mostly Nordmann’s Greenshanks have been recorded in very small numbers throughout Southeast Asia, and there are few places where it has been reported regularly. In Myanmar, for example, it was rediscovered after a gap of almost 129 years. The total count recorded by the Asian Waterbird Census (AWC) in 2006 for Myanmar was 28 birds with 14 being the largest number at a single locality (Naing 2007). In 2011–2012, Nordmann’s Greenshank was found three times in Sumatera Utara province, N Sumatra. -

Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris Pusilla in Brazil: Occurrence Away from the Coast and a New Record for the Central-West Region

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia 27(3): 218–221. SHORT-COMMUNICARTICLEATION September 2019 Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla in Brazil: occurrence away from the coast and a new record for the central-west region Karla Dayane de Lima Pereira1,3 & Jayrson Araújo de Oliveira2 1 Programa Integrado de Estudos da Fauna da Região Centro Oeste do Brasil (FaunaCO), Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, GO, Brazil. 2 Departamento de Morfologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, GO, Brazil. 3 Corresponding author: [email protected] Received on 27 March 2019. Accepted on 16 September 2019. ABSTRACT: The Semipalmated Sandpiper, Calidris pusilla, is a Western Hemisphere migrant shorebird for which Brazil forms an internationally important contranuptial area. In Brazil, the species main contranuptial areas is along the Atlantic Ocean coast, in the north and northeast regions. In addition to these primary contranuptial areas, there are also records of vagrants widely distributed across Brazil. Here, we review the occurrence of vagrants of this species in Brazil, and document a new record of C. pusilla for the central-west region and a first occurrence for the state of Goiás. KEY-WORDS: geographical distribution, Nearctic migrant, shorebird, state of Goiás, vagrant. The Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla (Linnaeus, of Mato Grosso (Cintra 2011, Levatich & Padilha 2019) 1766) is a migratory shorebird species that breeds in and two in the municipality of Corumbá, state of Mato the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions of Alaska and Canada Grosso do Sul (Serrano 2010, Tubelis & Tomas 2003). (Andres et al. 2012, IUCN 2019). Every year, as the However, there is no evidence that these records have northern autumn approaches, Arctic populations fly been correctly identified, as individuals appear not to from 3000 to 4000 km to South America (Hicklin & have been collected and sent to a scientific collection, nor Gratto-Trevor 2010). -

Field Identification of Smaller Sandpipers Within the Genus <I

Field identification of smaller sandpipers within the genus C/dr/s Richard R. Veit and Lars Jonsson Paintings and line drawings by Lars Jonsson INTRODUCTION the hand, we recommend that the reader threeNearctic species, the Semipalmated refer to the speciesaccounts of Prateret Sandpiper (C. pusilia), the Western HESMALL Calidris sandpipers, affec- al. (1977) or Cramp and Simmons Sandpiper(C. mauri) andthe LeastSand- tionatelyreferred to as "peeps" in (1983). Our conclusionsin this paperare piper (C. minutilla), and four Palearctic North America, and as "stints" in Britain, basedupon our own extensivefield expe- species,the primarilywestern Little Stint haveprovided notoriously thorny identi- rience,which, betweenus, includesfirst- (C. minuta), the easternRufous-necked ficationproblems for many years. The hand familiarity with all sevenspecies. Stint (C. ruficollis), the eastern Long- first comprehensiveefforts to elucidate We also examined specimensin the toed Stint (C. subminuta)and the wide- thepicture were two paperspublished in AmericanMuseum of Natural History, spread Temminck's Stint (C. tem- Brtttsh Birds (Wallace 1974, 1979) in Museumof ComparativeZoology, Los minckii).Four of thesespecies, pusilla, whichthe problem was approached from Angeles County Museum, San Diego mauri, minuta and ruficollis, breed on the Britishperspective of distinguishing Natural History Museum, Louisiana arctictundra and are found during migra- vagrant Nearctic or eastern Palearctic State UniversityMuseum of Zoology, tion in flocksof up to thousandsof -

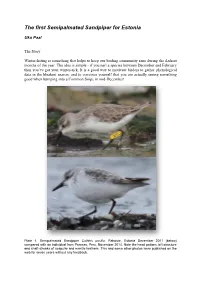

The First Semipalmated Sandpiper for Estonia

The first Semipalmated Sandpiper for Estonia Uku Paal The Story Winter-listing is something that helps to keep our birding community sane during the darkest months of the year. The idea is simple - if you nail a species between December and February then you’ve got your winter-tick. It is a good way to motivate birders to gather phenological data in the bleakest season, and to convince yourself that you are actually seeing something good when bumping into a Common Snipe in mid-December! Plate 1. Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla. Rahuste, Estonia December 2011 (below) compared with an individual from Paracas, Peru, November 2014. Note the head pattern, bill structure and shaft-streaks of scapular and mantle feathers. This and some other photos were published on the web for seven years without any feedback. The late autumn of 2011 looked perfect to get some lingering migrants, as the warm weather was going strong well into January. In the first few days of December, I usually try to get to the west coast in the hope of some lost migrants, and so I packed myself off with Mari and Margus and headed to Saaremaa. Coastal meadows here are often hold a good selection of birds... We start at Türju lighthouse on the 3rd of December with a seawatching session. Nothing shocking this time with the usual Red-throated Divers, Razorbills, and a lone Red-necked Grebe passing. Rahuste coastal meadow is obviously the next site – a well-known place for getting some late birds. The situation looks exceptionally good. After trampling the area for couple of hours we manage to find White Wagtail, Skylark, five Common Snipe, two Pintail, 15 Lapwing, two Common Redshank, Grey Plover and Brant Goose among many other birds. -

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List The target species list (species to be surveyed) should not change over the course of the study, therefore determining the target species list is an important project design task. Because waterbirds, including shorebirds, can occur in very high numbers in a census area, it is often not possible to count all species without compromising the quality of the survey data. For the basic shorebird census program (protocol 1), we recommend counting all shorebirds (sub-Order Charadrii), all raptors (hawks, falcons, owls, etc.), Common Ravens, and American Crows. This list of species is available on our field data forms, which can be downloaded from this site, and as a drop-down list on our online data entry form. If a very rare species occurs on a shorebird area survey, the species will need to be submitted with good documentation as a narrative note with the survey data. Project goals that could preclude counting all species include surveys designed to search for color-marked birds or post- breeding season counts of age-classed bird to obtain age ratios for a species. When conducting a census, you should identify as many of the shorebirds as possible to species; sometimes, however, this is not possible. For example, dowitchers often cannot be separated under censuses conditions, and at a distance or under poor lighting, it may not be possible to distinguish some species such as small Calidris sandpipers. We have provided codes for species combinations that commonly are reported on censuses. Combined codes are still species-specific and you should use the code that provides as much information as possible about the potential species combination you designate. -

The Systematic Position of the Surfbird, Aphriza Virgata

THE SYSTEMATIC POSITION OF THE SURFBIRD, APHRIZA VIRGATA JOSEPH R. JEHL, JR. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104 The taxonomic relationships of the Surfbird, ( 1884) elevated the tumstone-Surfbird unit Aphriza virgata, have long been one of the to family rank. But, although they stated (p. most controversial problems in shorebird clas- 126) that Aphrizu “agrees very closely” with sification. Although the species has been as- Arenaria, the only points of similarity men- signed to a monotypic family (Shufeldt 1888; tioned were “robust feet, without trace of web Ridgway 1919), most modern workers agree between toes, the well formed hind toe, and that it should be placed with the turnstones the strong claws; the toes with a lateral margin ( Arenaria spp. ) in the subfamily Arenariinae, forming a broad flat under surface.” These even though they have reached no consensuson differences are hardly sufficient to support the affinities of this subfamily. For example, familial differentiation, or even to suggest Lowe ( 1931), Peters ( 1934), Storer ( 1960), close generic relationship. and Wetmore (1965a) include the Arenariinae Coues (1884605) was uncertain about the in the Scolopacidae (sandpipers), whereas Surfbirds’ relationships. He called it “a re- Wetmore (1951) and the American Ornithol- markable isolated form, perhaps a plover and ogists ’ Union (1957) place it in the Charadri- connecting this family with the next [Haema- idae (plovers). The reasons for these diverg- topodidae] by close relationships with Strep- ent views have never been stated. However, it silas [Armaria], but with the hind toe as well seems that those assigning the Arenariinae to developed as usual in Sandpipers, and general the Charadriidae have relied heavily on their appearance rather sandpiper-like than plover- views of tumstone relationships, because schol- like. -

Purple Sandpiper

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: January 13, 2016 Calidris maritima (Purple Sandpiper) Priority 1 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Class: Aves (Birds) Order: Charadriiformes (Plovers, Sandpipers, And Allies) Family: Scolopacidae (Curlews, Dowitchers, Godwits, Knots, Phalaropes, Sandpipers, Snipe, Yellowlegs, And Woodcock) General comments: Recent surveys suggest population undergoing steep population decline within 10 years. IFW surveys conducted in 2014 suggest population declined by 49% since 2004 (IFW unpublished data). Maine has high responsibility for wintering population, regional surveys suggest Maine may support over 1/3 of the Western Atlantic wintering population. USFWS Region 5 and Canadian Maritimes winter at least 90% of the Western Atlantic population. Species Conservation Range Maps for Purple Sandpiper: Town Map: Calidris maritima_Towns.pdf Subwatershed Map: Calidris maritima_HUC12.pdf SGCN Priority Ranking - Designation Criteria: Risk of Extirpation: NA State Special Concern or NMFS Species of Concern: NA Recent Significant Declines: Purple Sandpiper is currently undergoing steep population declines, which has already led to, or if unchecked is likely to lead to, local extinction and/or range contraction. Notes: Recent surveys suggest population undergoing steep population decline within 10 years. IFW surveys conducted in 2014 suggest population declined by 49% since 2004 (IFW unpublished data). Maine has high responsibility for wintering populat Regional Endemic: Calidris maritima's global geographic range is at least 90% contained within the area defined by USFWS Region 5, the Canadian Maritime Provinces, and southeastern Quebec (south of the St. Lawrence River). Notes: Recent surveys suggest population undergoing steep population decline within 10 years. IFW surveys conducted in 2014 suggest population declined by 49% since 2004 (IFW unpublished data). -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

The All-Bird Bulletin

Advancing Integrated Bird Conservation in North America Spring 2014 Inside this issue: The All-Bird Bulletin Protecting Habitat for 4 the Buff-breasted Sandpiper in Bolivia The Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Conserving the “Jewels 6 Act (NMBCA): Thirteen Years of Hemispheric in the Crown” for Neotropical Migrants Bird Conservation Guy Foulks, Program Coordinator, Division of Bird Habitat Conservation, U.S. Fish and Bird Conservation in 8 Wildlife Service (USFWS) Costa Rica’s Agricultural Matrix In 2000, responding to alarming declines in many Neotropical migratory bird popu- Uruguayan Rice Fields 10 lations due to habitat loss and degradation, Congress passed the Neotropical Migra- as Wintering Habitat for tory Bird Conservation Act (NMBCA). The legislation created a unique funding Neotropical Shorebirds source to foster the cooperative conservation needed to sustain these species through all stages of their life cycles, which occur throughout the Western Hemi- Conserving Antigua’s 12 sphere. Since its first year of appropriations in 2002, the NMBCA has become in- Most Critical Bird strumental to migratory bird conservation Habitat in the Americas. Neotropical Migratory 14 Bird Conservation in the The mission of the North American Bird Heart of South America Conservation Initiative is to ensure that populations and habitats of North Ameri- Aros/Yaqui River Habi- 16 ca's birds are protected, restored, and en- tat Conservation hanced through coordinated efforts at in- ternational, national, regional, and local Strategic Conservation 18 levels, guided by sound science and effec- in the Appalachians of tive management. The NMBCA’s mission Southern Quebec is to achieve just this for over 380 Neo- tropical migratory bird species by provid- ...and more! Cerulean Warbler, a Neotropical migrant, is a ing conservation support within and be- USFWS Bird of Conservation Concern and listed as yond North America—to Latin America Vulnerable on the International Union for Conser- Coordination and editorial vation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. -

Nesting Birds and Two Fox Species

BIODIVERSITY CHANGES AT THE INTERFACE OF MARINE AND TERRESTRIAL ECOSYSTEMS: Nesting birds and two fox species David R. Klein, University of Alaska Fairbanks, AK Heather Renner, Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, Homer, AK Richard Kleinleder, URS, Homer, AK Climate warming in the Arctic and Subarctic has brought about decline in the seasonal extent of sea ice, rising sea levels, accelerated coastal erosion, and changes in the distribution and biodiversity of species of mammals and birds. What are the consequences of these climate- induced changes for nesting birds and resident mammals at the ecosystem and species levels on the St. Matthew Islands? The St. Matthew Islands, now part of Alaska, were discovered during an exploration cruise by Lieutenant Synd of the Russian Navy in the mid-1760’s. Captain Cook “re-discovered” and named the islands in 1778. •In 1909, St. Matthew and adjacent islands were given protective status as a bird reserve by President Theodore Roosevelt, designated as the Bering Sea Reservation These islands attained “Wilderness” status within the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge in 1980 Several million sea birds, including >15 species, nest on the St. Matthew Islands, and walrus, sea lions, and seals haul out there Pinnacle Is. There are two vertebrate species endemic to these islands McKay’s bunting Plectrophenax hyperboreus Singing vole Microtus abreviatus Ian Jones photo The St. Mathew Islands are the nesting location for the major portion of the Bering Sea rock sandpiper population The St. Matthew Islands include 3 islands, the largest is about 52 km long, as the biologist walks, and averages ~6 km wide. -

Migratory Birds Index

CAFF Assessment Series Report September 2015 Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index ARCTIC COUNCIL Acknowledgements CAFF Designated Agencies: • Norwegian Environment Agency, Trondheim, Norway • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland • Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Reykjavik, Iceland • Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Greenland • Russian Federation Ministry of Natural Resources, Moscow, Russia • Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Stockholm, Sweden • United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska CAFF Permanent Participant Organizations: • Aleut International Association (AIA) • Arctic Athabaskan Council (AAC) • Gwich’in Council International (GCI) • Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) • Russian Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) • Saami Council This publication should be cited as: Deinet, S., Zöckler, C., Jacoby, D., Tresize, E., Marconi, V., McRae, L., Svobods, M., & Barry, T. (2015). The Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, Akureyri, Iceland. ISBN: 978-9935-431-44-8 Cover photo: Arctic tern. Photo: Mark Medcalf/Shutterstock.com Back cover: Red knot. Photo: USFWS/Flickr Design and layout: Courtney Price For more information please contact: CAFF International Secretariat Borgir, Nordurslod 600 Akureyri, Iceland Phone: +354 462-3350 Fax: +354 462-3390 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.caff.is This report was commissioned and funded by the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF), the Biodiversity Working Group of the Arctic Council. Additional funding was provided by WWF International, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). The views expressed in this report are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Arctic Council or its members.